by Frances Wilson, Interlude

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the Petrarch Sonnets, inspired by the love poetry of the 14th-century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. “Oh!” I enthused, “those poems …!” She entered her studio. “We don’t need them,” she said, and closed the door. I was deflated. And dumbfounded.”

Paul Roberts feels that music comes from sources beyond simply itself – from, for example, the composer’s life experience, the influence of others, and, in the case of Liszt, poetry and literature, and that as pianists we do the music, and its composer, a disservice by not paying attention to these external sources of inspiration. In his engaging, eloquent and highly readable text, Roberts explores what he believes to be an inseparable bond between poetry and the piano music of Franz Liszt, and how literary inquiry affects musical interpretation and performance. For Roberts, an appreciation of the poetry which inspired or informed Liszt’s music gives the pianist, and listener, significant insights into the composer’s creative imagination, bringing one closer to his music and allowing a deeper understanding, and, for the performer, a richer, more multi-dimensional interpretation of the music. It also offers a better appreciation of Liszt the man: too often dismissed as a superficial showman, in this book Roberts reveals Liszt as a man of passionate intellectual and emotional curiosity, who read widely and with immense discernment, all of which is reflected in his music. As Alfred Brendel said, “Liszt’s music….projects the man”.

Paul Roberts © Viktor Erik Emanuel

Poetry and literature were meat and drink to Franz Liszt, who performed in and attended the cultural salons of 1830s Paris where he knew writers such as Victor Hugo and George Sand. He was familiar with the writing of Byron, Sénancour, Goethe, Dante, Petrarch and others, and his scores are littered with literary quotations which offer fascinating glimpses into the breadth of his creative imagination and what that literature meant to him. For the pianist, they provide an opportunity to “live inside his mind” and open “our imaginations to the wonder of his music”.

Perhaps the most obvious connection between Liszt and poetry is his Tre Sonetti del Petrarca – the three Petrarch Sonnets. They began life as songs which Liszt later arranged for piano solo, and included them in the Italian volume of his Années de pèlerinage. Liszt and his lover Marie d’Agoult spent two years in Italy and it was here that Liszt was exposed to the marvels of Italian Renaissance art and architecture and the poetry of Dante and Petrarch.

The poetry of Petrarch was central to Liszt’s creative imagination and in his triptych inspired by the Italian poet’s sonnets, we find an extraordinary depth of expression and emotional breadth. In the chapter ‘The Music of Desire’, Roberts explores Petrarch’s sonnets in detail and demonstrates how Liszt translates the passion of the poet into some of the finest writing for piano by Liszt, or indeed anyone else.

Perhaps because I have studied and performed these pieces myself, a study which included close reference to Petrarch’s poetry, it is here that I find Roberts’ argument most persuasive, that the pianist really needs this literary context and understanding to bring the music fully to life. He shows how Liszt responds to the ebb and flow of emotions in Petrarch’s writing, in particular in the most passionately dramatic of the three sonnets, No. 104, “Pace no trovo” (I find no peace), where the poet veers almost schizophrenically between extremes of emotion, from the depths of despair to ecstasy.

Franz Liszt

Subsequent chapters explore other great piano works – the extraordinary B-minor Sonata which Roberts believes is firmly connected to that pinnacle of nineteenth century European literature, Goethe’s Faust, the existentialism of Vallée d’Obermann, a work which exemplifies the Romantic spirit, and its relationship with Etienne de Sénancour’s cult novel Obermann, the “aura” of Byron and his Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage which pervade the Swiss volume of the Années alongside Liszt’s personal experience of the majestic landscape of Switzerland and the Alps. The final chapter explores the Dante Sonata and Liszt’s reverence for The Divine Comedy at a time when Dante’s poetry was being rediscovered by English and European Romantic writers like Keats, Coleridge, Shelley and Stendhal. Throughout, Roberts conveys the power of literature to awaken and inspire the Romantic imagination and sensibilities, and demonstrates how this might inform the way one performs Liszt’s music – from the physical cadence of poetry to its drama, narrative arc and emotional impact which had such a profound effect on Liszt and which infuses his music in almost every note. Here Liszt finds a new kind of expression in which, in his own words, music becomes “a poetic language, one that, better than poetry itself perhaps, more readily expresses everything in us that transcends the commonplace, everything that eludes analysis”.

A useful Appendix explores the influence of other poets such as Alphonse de Lamartine and Lenau, with analysis of other pianos works, including Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude, the Mephisto Waltz, the two St Francis legends, and Mazeppa, inspired by a poem by Victor Hugo.

In this book, Paul Roberts reveals the essence of Liszt literary world, providing the pianist with valuable insight and inspiration with which to appreciate, shape and perform his music.

Reading Franz Liszt: Revealing the Poetry behind the Piano Music is published by Amadeus Press, an imprint of Rowman & Littlefield, USA.

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances.

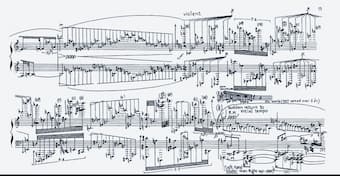

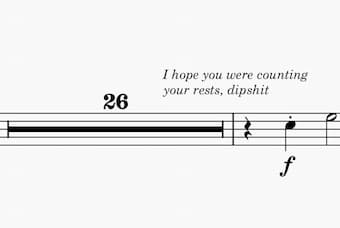

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances. There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.