by

Put Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe or La Valse, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, or Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances—or pretty much anything by Prokofiev or Mahler—in front of me and I’ll play them happily over and over, and I have. But dear readers I must confess there are pieces of music I hope I never have to play again, and I’m not alone. Some works we professionals play to death; others just get under our skin. Let me explain.

Perhaps you love the Pachelbel Canon. It’s a popular piece for weddings. While the violins soar through multiple variations the poor cellist plays the same 8 notes s-l-o-w-l-y, repeating the pattern D-A-B-F#-G-D-G-A. Each iteration takes 4 measures and is played 28 times! And some perform it extra deliberately. It’s a bit like detention for cellists! Funny enough, once a local National Public Radio classical music radio station played this continuously until they’d met their pledge drive donation goals. I imagine some listeners silently (or loudly) screamed, “Make it stop…”

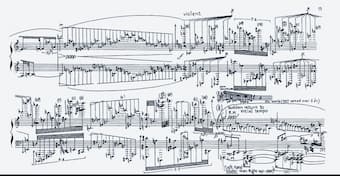

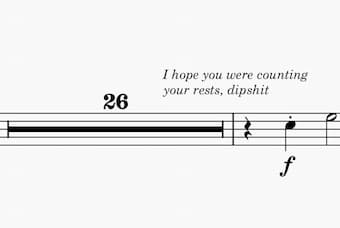

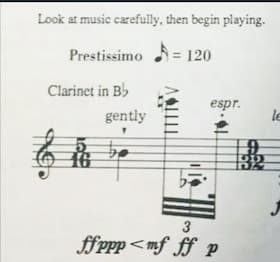

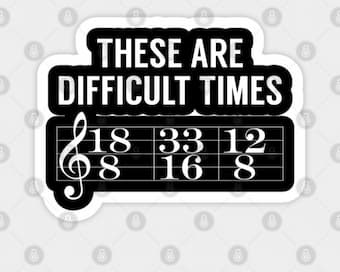

Crazy instructions!

Ravel’s Bolero is another very popular piece of music but not for the snare drum player. He or she has to play the two-bar 24-note pattern unrelentingly steady in rhythm starting very softly or pianissimo and increasing in volume to a dramatic fortissimo. The piece is 430 bars; about 15 minutes. Need I do the math? That’s 5,144 snare drum strokes. Talk about repetition… And since we’re counting, did you know Tchaikovsky was fond of the cymbals? During Swan Lake, there are a total of 1,214 cymbal crashes in each performance. One of my colleagues sat very close to the percussion section. The din after 21 performances and 29,715 cymbal crashes, left her shell-shocked.

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances.

Other pieces can be tiresome because of the ubiquitous numbers of performances of them. One colleague told me, “I had a nightmare that I was playing Messiah, and I woke up and it was true!” Ditto Tchaikovsky Nutcracker. I remember during the Holidays the Minnesota Orchestra would be divided in two. Half played 10 Messiah performances and the other half performed The Nutcracker Ballet 13 times in two weeks—twice on weekend days—every season for years. May I remind you of the temperatures in December in Minnesota that dip well below zero? The nearest parking was several blocks away. I’d drag my cello in the bitter cold to the huge auditorium hoping to thaw in time for the performances.

There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

There are many works that are ever-present in our repertoire. Sometimes the consequences of often-played repertoire are that they are given short shrift in rehearsal. No musician enjoys walking on eggshells during a concert or conversely slamming through a work such as Liszt Les Preludes, Orff’s Carmina Burana, Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet or the Symphonies No. 4 or No. 5, or even Handel’s Water Music. There are always tricky passages and difficult transitions that should be rehearsed for ensemble.

Perhaps a particular piece brings back bad memories. Did your mom force you to play Für Elise by Beethoven or Haydn Trumpet Concerto for Aunt Betsy, and Grandma Rose and every person who was invited over for dinner when you were growing up no matter how you protested? My parents were guilty.

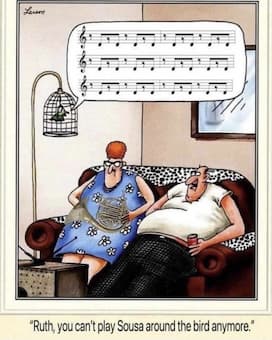

Please don’t blame the poor second violins and violas (and sometimes the horns) when they almost drop their instruments in boredom. While you’re elegantly waltzing, they have to play endless off beats in Strauss waltzes or Sousa Marches, and they rarely get to play the melody.

Unplayable!

We really have no patience for a composer who doesn’t know our instrument and writes nothing but rests. We relish performing pieces that are challenging unless the composer’s metronome markings suggest an unplayable tempo, contradictory (or silly) instructions, or if he or she uses an undecipherable meter, like something you’ve seen in a calculus textbook watch out. That’s when we might throw up our hands!

Even soloists must bemoan the fact that certain concertos, favorites and crowd-pleasers, are requested in every city despite the fact that an artist hopes to perform more unfamiliar works worth playing and hearing. But that said, we never tire of the great masterworks: Brahms, Sibelius, Barber, and Mendelssohn Violin Concertos, Brahms, Schumann, Grieg, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, and Tchaikovsky Piano Concertos and Beethoven of course.

Pianist Jon Kimura Parker tells us that he first played the Beethoven Third Piano Concerto in C minor, when he was twelve years old. It was his concerto debut in Vancouver, with the Vancouver Symphony and the first concerto he ever learned. This week, the 50th anniversary of performing the work, he still finds new revelations, after playing it countless times. Beethoven’s vehement music continues to speak to us. Surely music wouldn’t be where it is today without him. Listen to this rendition of the last movement of Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto during Covid. “One can only imagine what Beethoven would think of all of this,” says Parker. “That his music is being performed so much even now, when our logistic preparations have required extra imagination, would surely boggle his mind!”

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.

Rather than predictable as some music is, this music never ceases to amaze performers and listeners alike. But even the masterworks of our repertoire benefit from a fresh approach by the artist and/or new ideas from the conductor.

My suggestion for programing a recital, a small ensemble concert, or a full orchestra season: it would be wise for small ensemble artistic directors, orchestra managements, and conductors to consider not only “good box office” but also what will challenge, inspire, and stimulate the musicians. That’s no secret!

No comments:

Post a Comment