Francisco Beltran Buencamino Sr

It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, February 14, 2025

Francisco Beltran Buencamino, Sr. - his music and his life

Francisco Beltran Buencamino was born on the 5th of November, 1883 in San Miguel de Mayumo, Bulacan. He is the sixth of ten children of Fortunato Buencamino and Luisa Beltran. His father was a church organist and band master, and his mother, a singer. Francisco was married to Pilar Luceno and they had two children, both of whom also took up music.

Francisco first learnt music from his father. At age 12, he could play the organ. At 14, he was sent to study at the Liceo de Manila. There, he took up courses in composition and harmony under Marcelo Adonay. He also took up pianoforte courses under a Spanish music teacher. He did not finish his education as he became interested in the sarswela.

In the early 1900s, Francisco Buencamino taught music at the Ateneo de Manila and at the Centro Escolar de Senoritas. At the latter, he founded the Conservatory of Music and was its head until 1938. At the same time, he also handled music lessons at the Liceo de Manila. He founded the Buencamino Music Academy in 1930. It was authorized by the Department of Public Instruction to grant music degrees. Some of his pupils were Nicanor Abelardo, Ernestina Crisologo, Estela Velasco, Beatrice Alba, and Amelia Hidalgo. In the 1940s, he started working as a musical director. He also composed music for films produced by Sampaguita Pictures, LVN and Excelsior. For a time, Francisco Buencamino frequently acted on stage. He also collaborated on the plays written and produced by Aurelio Tolentino. The Philippine Music Publishers, which Buencamino established, undertook the printing of his more important compositions, but it was not a successful venture.

Some of the sarswelas he wrote are: "Marcela" (1904), "Si Tio Celo" (1904) and "Yayang " (1905). In 1908, the popularity of the sarswela started to wane because of American repression and the entry of silent movies. Francisco Buencamino then turned to composing kundimans.

One of his earliest compositions is "En el bello Oriente" (1909), which uses Jose Rizal's lyrics. "Ang Una Kong Pag-ibig", a popular kundiman, was inspired by his wife. In 1938, he composed an epic poem which won a prize from the Far Eastern University during one of the annual carnivals. His "Mayon Concerto" is considered his magnum opus. Begun in 1943 and finished in 1948, "Mayon Concerto" had its full rendition in February 1950 at the graduation recital of Rosario Buencamino at the Holy Ghost College. "Ang Larawan" (1943), also one of his most acclaimed works, is a composition based on a Balitaw tune. The orchestral piece, "Pizzicato Caprice" (1948) is a version of this composition. Many of his other compositions were lost during the Japanese Occupation, when he had to evacuate his family to Novaliches, Rizal.

As a musical director, he was involved in anumber of movies such as "Mabangong Bulaklak", "Ang Ibong Adarna", "Mutya ng Pasig", and "Alitaptap".

Francisco Buencamino died on the 16th of October, 1952. in the same year, he was given a posthumous Outstanding Composer Award by the Manila Music Lovers Society.

Additional Information: Pianist Cecile Licad, is his grand niece. Composers Willy Cruz, Lorrie Ilustre and Nonong Buencamino, and actor Noni Buencamino are his grandnephews.

Note: I've lost the original sources for this post. But they can all be surely found in the College of Music Library, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City.

One day we'll see...

The nation celebrates the 130th Birth Anniversary of National Artist Jovita Fuentes.

Long before Lea Salonga made her mark on Broadway, Jovita Fuentes had already captivated audiences with her portrayal of Cio-Cio San in Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly at the Teatro Municipale di Piacenza in Italy. Her performance was celebrated as the "most sublime interpretation of the role." This achievement is particularly noteworthy given that it occurred during a period when the Philippines and its people were largely unknown in Europe. Prior to this, Fuentes was teaching at the University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music in 1917 before relocating to Milan in 1924 to pursue advanced vocal studies.

After eight months of rigorous training, she made her stage debut in Piacenza. Subsequently, she undertook a series of musical performances across Europe, portraying characters such as Liu Yu in Puccini’s Turandot, Mimi in Puccini’s La Bohème, Iris in Pietro Mascagni’s Iris, and the title role in Salome, which was personally offered to her by composer Richard Strauss. Additionally, she was honored with the remarkable title of “Embahadora de Filipinas a su Madre Patria” by Spain in recognition of her accomplishments.

To read more about NA Fuentes, please visit: https://ncca.gov.ph/.../national-artists.../jovita-fuentes/

Morissette - LOVE THE PHILIPPINES (Official Music Video)

Transcript

Follow along using the transcript.

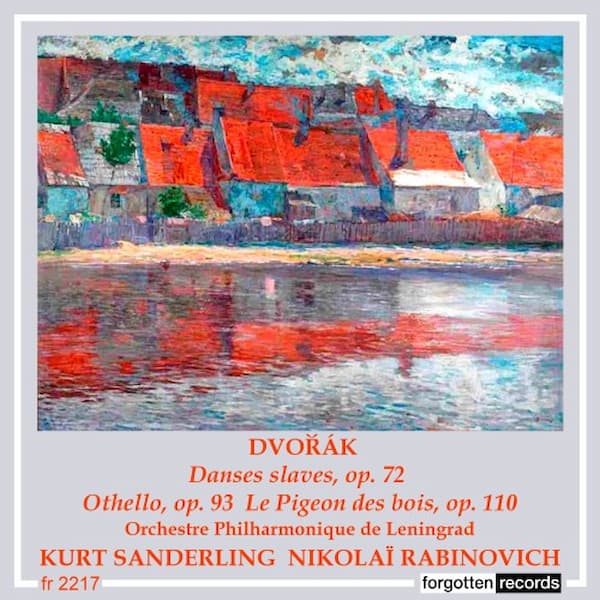

Widowhood and a Murder: Dvořák’s Holoubek

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

Antonín Dvořák (1841–1904) loved the poetry of Karl Jaromir Erben, particularly his collection of Czech folk ballads, The Garland, published in 1853. Starting in 1896, once he’d finished his nine symphonies and his other major orchestral works, Dvořák used the ballads from The Garland as the basis for a series of ‘orchestral ballads’. He started with Vodník (‘The Water Goblin’, b195), Polednice (‘The Noon Witch’, b196), and Zlatý kolovrat (‘The Golden Spinning-Wheel’, b197) all at the same time, completing them just a few weeks later, and then started on Holoubek (‘The Wild Dove’, b198) a few months later, completing it in November 1896.

Antonín Dvořák, 1882

This development of the symphonic poem, all based on one literary source, was not unprecedented for Dvořák. Earlier works had literary elements, the most familiar perhaps being in his works written in America (the New World Symphony and the American Quartet).

The Garland, or, to give it its full name, The Garland of National Legends, was a cycle of 13 ballads. Holoubek, or The Dove (The Wood Dove, the Wood Pigeon) story starts in a graveyard. A widow mourns her recently departed husband and is seen by a passing youth (handsome, of course). After three days of resistance, she accedes to his demands and in a month they are married. The story then turns – she’s a widow because she gave her first husband a deadly potion so she could marry the handsome youth, and then at the end of the poem, after 3 years with her new husband, the sound of the dove, cooing in the oak tree over her first husband’s grave, drives her to suicide.

The tone poem opens with a funeral march, with a recurring march-beat of the funeral procession under the melodies. The flutes and violins bring in the young widow, but the following subject, on oboe and trumpets, belies the presented innocence. The widow’s tears, sarcastically presented in the flutes and violins, are another indication of her false heart. The handsome young man is signalled by a distant trumpet. The funeral march continues, but in a more spritely manner – perhaps the inconsolable widow is approachable after all!

The central section is the wedding of the widow and her new husband.

In the final section we return to the graveyard and the mournful call of the dove in the oak tree above the husband’s grave. Dvořák gives this an eery setting with harp and strings, wailing flutes, and a crying oboe. The widow / bride is driven to remorse and drowns herself, and the funeral march returns at the end. Although Erben’s poem ends with a pitiless description of her grave – no tombstone and her head laid only on a rock, buried in the middle of a field – Dvořák gives us an optimistic ending with a return of the dove’s song and the minor key turned to major one.

Antonín Dvořák: Holoubek, Op. 110, B. 198

Nikolai Ravinovich

This recording was made in 1954 with Nikolai Rabinovich conducting the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra.

Nikolai Rabinovich (1908–1972) graduated from the Leningrad Conservatory in 1931 and was appointed professor of conducting there in 1968. His students included Yuri Simonov, Neeme Järvi, Vladislav Chachin, Vitaliy Kutsenko, and Victor Yampolsky, all of whom had exemplary conducting careers.

The Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra, now the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic, was founded in 1802 and started as the orchestra for the Court of Alexander III of Russia. Its period of greatest achievement occurred under the leadership of Yevgeny Mravinsky, who led it for 50 years (1938–1988). This saw its first tours to the west and the start of their studio recordings. Under Mravinsky, the orchestra recorded seven of Shostakovich’s symphonies.

Performed by

Nikolai Rabinovich

The Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra

Recorded in 1954

Official Website

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter

Buried Treasures: Felix Mendelssohn: Concerto for Piano, Violin and Strings in D Minor (1822)

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Felix Mendelssohn

When Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) died at the incredibly young age of thirty-eight, he simply had not yet made arrangements for literally hundreds of unpublished musical manuscripts and artworks, alongside thousands of personal letters to and from the composer. During his lifetime, and for a short period thereafter — with a large number of music published during a period of two years following his death — Mendelssohn was almost universally lauded musical genius. What is more, Mendelssohn was also the artistic director and chief conductor of The Gewandhaus (Garment House) in Leipzig, a venue that has long been recognized as one of the most important performing centers in Europe. Under his tutelage and leadership, the Gewandhaus Orchestra became a cultural institution. Mendelssohn not only initiated the revival of music by Bach, Handel, Haydn and Mozart, he also assured that his brand of musical historicism was disseminated throughout Europe and beyond. With the help of Richard Wagner who declared “Judaism the evil conscience of our modern civilization” in his 1850 treatise Judaism in Music, Mendelssohn and his music were quickly subjected to deliberate and systematic forms of historical revisions. And when Wagner declared Mendelssohn’s music “an icon of degenerate decadence,” publishers far and wide declined to make his manuscripts and letters public.

Of course, Wagner was not able to completely erase or dismiss Mendelssohn’s influence on Germanic arts, nor was he able to excise him from music-historical memory. This, of course, led to serious irritation within the propaganda machinery of Nazi Germany, and his name was promptly added to various lists of forbidden artists. At that time, according to Stephen Somary, founder and artistic director of the Mendelssohn Project, “a majority of Mendelssohn manuscripts — both published and unpublished — were housed in the basement of the Berlin State Library. They were smuggled to Warsaw and Krakow during the winter of 1936/37, and when the city fell under Nazi control in 1939, they were hurriedly smuggled out again and disbursed to locations wide and far between.” Following WWII, the majority of manuscripts remained buried behind the Iron Curtain. Haltingly, various unknown versions and unknown compositions were discovered and made available in one form or another.

The Gewandhaus

Initially, these efforts focused on works Mendelssohn composed before his 14th birthday, pieces that had originally been presented at private concerts at the Mendelssohn home. Among them various sonatas for viola and for violin, religious choral music, numerous piano compositions and even a fourth opera. But it also included a succession of concertos, among them a concerto for piano and string orchestra in A minor (1822) and two concertos for two pianos and full orchestra in E and A-flat, originating from 1823 and 1824, respectively.

The concerto for violin, piano and string orchestra in D minor was composed for an initial private performance with his best friend and violin teacher Eduard Rietz. On 3 July 1822, Mendelssohn revised the scoring, adding timpani and winds and the premiere of this version was apparently performed on the same day. For reasons detailed above, it remained unpublished until 1960, when the Astoria Verlag in Berlin issued a miniature score, edited and arranged by Clemens Schmalstich. In 1966, Theodora Schuster-Lott and Frieder Zschoch prepared a scholarly edition for the Deutsche Verlag für Music as part of the new Mendelssohn complete edition, “which was engraved, but never published except in a reduction by Walter-Heinz Bernstein for violin and two pianos.” Finally, in 1999 the 1960 miniature score was reissued in a scholarly edition with the wind and timpani parts added. And just in case you are wondering, the A-minor Piano Concerto of 1822 had until recently been unavailable in any edition, and the Concerto for two pianos and orchestra in E major, composed as a birthday gift for his sister Fanny, had to wait until 2003 before audiences could get a listen to the original version.

And just in case you are interested in all the works and versions by Felix Mendelssohn, they are now available to the general public and performing artists, have a quick look at this link!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)