by Georg Predota

Franz Liszt, 1858

Enjoying the shores of Lake Como with Marie d’Agoult in 1837, Franz Liszt (1811-1886) immersed himself in a close reading of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The idea of composing a symphony to Dante’s Divine Comedy, one that would combine music, poetry and the visual arts, gradually took shape. Initially, Liszt suggested that the performance might be accompanied by the projection of lanternslides, showing scenes painted by Bonaventura Genelli. Apparently, he even considered “the use of an experimental wind machine at the end of the first movement to evoke the winds of Hell.”

Dante and His Poem by Domenico di Michelino

In the event, in June 1855, Liszt wrote to his future son-in-law Richard Wagner. “So you are reading Dante. He’s good company for you, and I for my part want to provide you with a kind of commentary on that reading. I have long been carrying a Dante Symphony around in my head – this year I intend to finish it. Three movements, Hell, Purgatory and Paradise – the first two for orchestra alone, the last with chorus. When I visit you in the autumn I shall probably be able to bring it with me; and if you don’t dislike it you can let me inscribe your name on it.” Wagner was enthusiastic, but advised against including a choral finale on the grounds that “Paradise could not be depicted in music.”

Royal Theatre in Dresden

On the advice of Wagner, Liszt discarded the idea of a choral finale and added a brief setting for women’s voices of the first two verses of the “Magnificat,” all ending with a “Hallelujah.” When Liszt played the Dante symphony for Wagner in Zürich in October 1856, Wagner greatly disliked the fortissimo conclusion. He wrote in his autobiography, “If anything had convinced me of the man’s masterly and poetical powers of conception, it was the original ending of the Faust Symphony, in which the delicate fragrance of a last reminiscence of Gretchen overpowers everything, without arresting the attention by a violent disturbance. The ending of the Dante Symphony seemed to me to be quite on the same lines, for the delicately introduced “Magnificat” in the same way only gives a hint of a soft, shimmering Paradise. I was the more startled to hear this beautiful suggestion suddenly interrupted in an alarming way by a pompous, plagal cadence. No! I exclaimed loudly, not that, away with it! No majestic Deity! Leave us the fine soft shimmer!” Liszt kept both endings; the loud one is indicated in his version for two pianos, but in the orchestral score it is usually omitted. The Dante Symphony is dedicated to Richard Wagner, and the first performance took place at the Royal Theatre in Dresden on 7 November 1857. Liszt conducted, and Hans von Bülow—still married to Liszt’s daughter Cosima—wrote, “the occasion proved a fiasco.” The press was hostile and Liszt wrote that the performance was “very unsuccessful from lack of rehearsal.”

Sandro Botticelli: Chart of Hell

A published preface functioning as a program guided audiences through the composition, but the music continued to challenge audiences for decades to come. George Bernard Shaw reviewed the work in 1885 and wrote, “the manner in which the program was presented by Liszt could just as well represent a London house when the kitchen chimney is on fire.” In terms of musical narrative, the opening movement is entitled “Inferno” and guides us through the nine Circles of Hell. The “Gates of Hell” sing slow recitative-like themes, and at “The Vestibule and First Circle Hell” the music becomes frantic. When Dante and Virgil enter the “Second Circle of Hell,” the infernal “Black Wind” that perpetually shakes the damned greets them. Here we find the tragic love of Francesca, whose adulterous affair with her brother-in-law Paolo cost her life and soul. The “Black Wind” motif returns in the “Seventh Circle of Hell,” and Liszt writes, “this entire passage is intended to be a blasphemous mocking laughter.” The “Eight” and “Ninth Circles of Hell” present slightly varied themes, and Dante and Virgil gradually emerge from Hell. They ascend Mount Purgatorio in the second, initially solemn and tranquil movement. Dante and Virgil ascend the two terraces of Ante-Purgatory, where souls repent their sins. The “Seven Cornices of Mount Purgatory” represent the seven deadly sins, and “Earthly Paradise” guides the soul to Paradise. In the score, Liszt directs that the choir be hidden from the audience in the concluding “Magnificat.” Liszt wrote, “Art cannot portray heaven itself, only its image in the hearts of those souls, which have turned to the light of heavenly grace. Thus for us the radiance is still shrouded, although it increases with the clarity of understanding.”

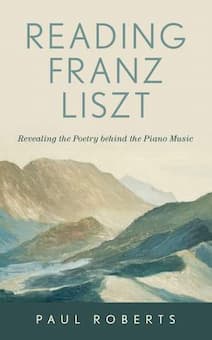

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the

In the introduction to his new book, pianist Paul Roberts recounts a conversation with “an elderly and much celebrated piano teacher” when he was just starting out as the inspiration for a lifetime’s fascination with literature and language and the essential connections between literature and music: “I introduced myself. I cannot remember quite how the topic came about, but within a few minutes we were talking about Liszt’s great triptych of piano pieces known as the