It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, August 29, 2025

I Don't Want To Talk About It (from One Night Only! Rod Stewart Live

Endless Love (Duet with Mariah Carey) (Live from Royal Albert Hall)

Time for Love: Messiaen’s Turangalîla Symphony

by Maureen Buja

In his exuberant post-WWII work, the Turangalîla Symphony, French composer Olivier Messiaen took the commission proposed by Serge Koussevitsky to heart: ‘compose the work as you like, in any style and length, with the instrumentation you would like, and I impose no time limit for you to deliver the work.’ Commissioned in 1945, the work started on 17 July 1946 and was completed and orchestrated by 29 November 1948. It was given its premiere on 2 December 1949 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Leonard Bernstein.

Olivier Messiaen

The work, some 75 minutes in length over 10 movements, was considered by Messiaen as ‘one of my richest works in terms of findings, it is also the most melodic, the warmest, the most dynamic and the most coloured’.

The title of the work combines two Sanskrit words, as explained by Messiaen: ‘Lîla literally means play, but play in the sense of divine action on the cosmos, the play of creation, of destruction and reconstruction, the play of life and death. Lîla is also Love. Turanga is Time, the time which runs like a galloping horse, time which slips like sand through the hourglass. Turanga is movement and rhythm. Turangalîla then signifies at one and the same time, a love song, a hymn to joy, time, movement, rhythm, life and death.’

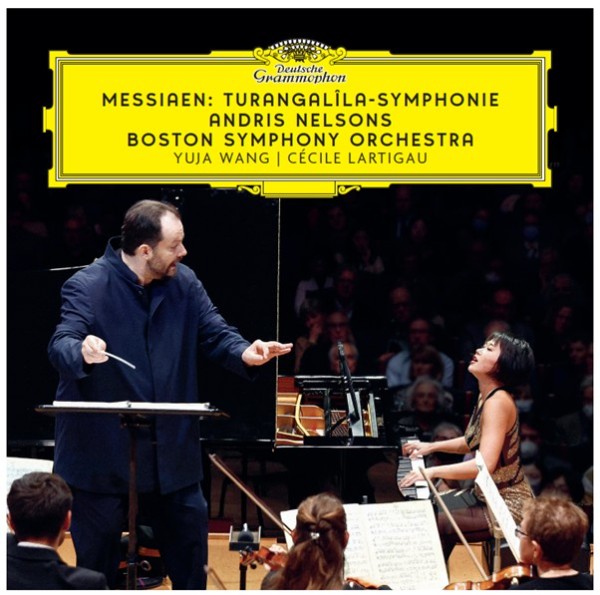

Andris Nelsons leads the Boston Symphony Orchestra in a performance that brings together Yuja Wang as piano soloist and Cécile Lartigau as ondes Martenot soloist. Each soloist has their work cut out for them. Wang tackles the part with verve, and Lartigau, as one of the rare ondes Martenot soloists, brings her skills to a tremendous high.

Yuja Wang (photo by Kirk Edwards)

Yuja Wang with Andris Nelsons and BSO, 2024

Cécile Lartigau, 2022 (Photo by Martin Kubik)

The ondes Martenot was a French electro-acoustic instrument that consists of a keyboard and a speaker (palme). The keyboard can be played in two ways: either as a regular keyboard or via a metal ring worn on the finger that moves on a wire. A drawer on the instrument permits control of dynamics and timbre.

The ring method of playing the ondes Martenot, with the left hand controlling dynamics and timbre (photo by 30rKs56MaE)

The piano solo part calls for a virtuoso pianist, and in Yuja Wang’s playing, this performance comes to life. At times, simply adding colour to massive movements in the brass and, at other times, carrying her own melodies and ideas, Wang takes control of the work in a way that unifies this large rambling work.

Messiaen organises the work around 4 musical themes that return: the Statue Theme (heard in the trombones in the first movement), the Flower Theme (played by the clarinets pianissimo, also in the first movement). The Love Theme doesn’t appear until the 6th movement, first in hushed strings. The last theme is chord-based and abstract and appears in the background as a unifying sound.

In the sixth movement, both present and future Messiaen seem to be present: we have the Love Theme presented and then expanded by the strings and ondes Martenot, and then the piano presents a stylised bird song. Bird song will become important to Messiaen’s later works, although later he tries to present it as it sounds, rather than stylising it as he does here. In Messiaen’s vision of this movement, ‘The two lovers are enclosed in love’s sleep. A landscape comes out from them…’.

Olivier Messiaen: Turangalîla-Symphonie – VI. Jardin du sommeil d’amour. Très modéré, très tendre

In later movements, the lovers take a love potion and become trapped in a passion that seems to drive them to the infinite. By the end of the work, in a glorious drive to the end, a massive F sharp major chord signals that ‘glory and joy are without end’.

Yuja Wang’s technical brilliance, in view for so many years, comes to the fore here, even in a work where the stage has to be shared with another keyboardist. It’s not a work that many have attempted, given both the demands of Messiaen’s writing and the lack of primary position for the pianist, but Wang brings something more to the proceedings. She matches the electro-acoustic sounds of the ondes Martenot with a degree of virtuosity that brings the piano part into greater prominence than in many other performances. The joy of Messiaen’s paean to love, celebrating its joy and passion, and even in those times when love sweeps all before it, comes to full fruition in this recording.

Messiaen: Turangalîla Symphony

Yuja Wang, piano;

Cécile Lartigau, ondes Martenot;

Boston Symphony Orchestra;

Andris Nelsons, cond.

Deutsche Grammophon 515785000

Release date: 18 July 2025 (previous digital-only release, December 2024)

Official Website

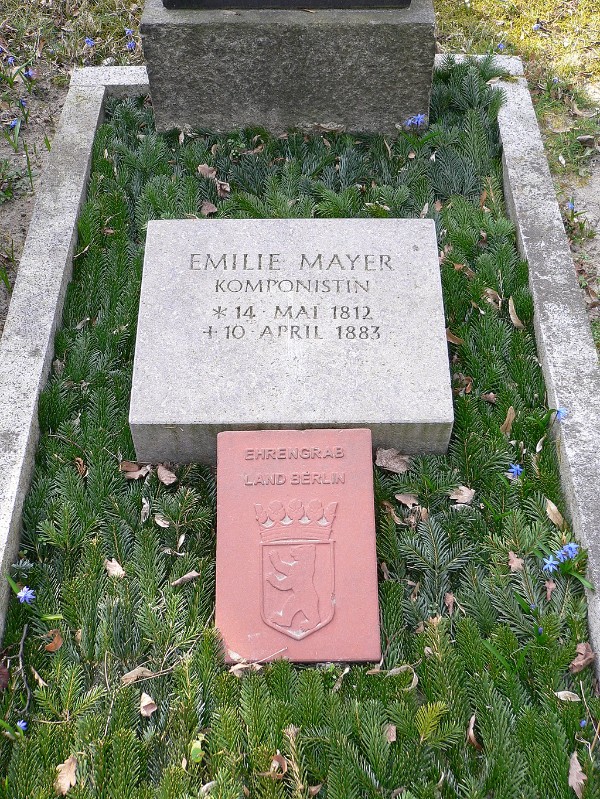

Composer Emilie Mayer: Was She the Female Beethoven?

by Emily E. Hogstad

Emilie Mayer

Mayer’s symphonies, chamber music, and piano works stand as testaments to both her talent and her determination to succeed in a male-dominated world.

Today, we’re looking at her gripping biography and how she made a hugely successful career for herself in her middle age, after enduring unimaginably painful personal loss.

Emilie Mayer’s Family

Emilie Mayer was born Emilie Luise Friderica Mayer on 14 May 1812. She was the third of five children and the eldest daughter.

The Mayers lived in the German town of Friedland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, roughly seventy kilometers from the Baltic Sea, where her father worked as an apothecary.

Tragedy struck the family a few years after Emilie’s birth, when her mother died. After her mother’s death, Emilie would have been expected to play the role of matriarch within the immediate family.

This may have been one reason why she never married…and one reason why she felt freer to become a composer.

Emilie Mayer’s Early Education

Emilie Mayer

It is believed that Emilie’s education was overseen by private tutors, as the local Latin school only accepted boys.

She began piano lessons at the age of five with a local organist named Carl Heinrich Ernst Driver.

She later wrote modestly, “After a few lessons… I composed variations, dances, little rondos, etc.” Driver was amused by his student’s precocity and helped notate these works for her.

Her father was thrilled by his daughter’s musical talent and supported her studies throughout her childhood.

Unexpected Tragedy Changes Everything

The defining event of Emilie’s life occurred in 1840, on the twenty-sixth anniversary of her mother’s burial, when her father shot and killed himself.

She dealt with her shock and grief by throwing herself into composing. But tragically, she suffered another major blow a few months later, when her teacher, Driver, also died.

Emilie was fast approaching thirty, without the economic protection a nineteenth-century husband would provide. Suddenly, she had to figure out what to do with the rest of her life, and how to make a living – and fast.

She decided to devote herself to music. Fortunately, her brothers supported the decision.

Moving to Szczecin

After her father’s affairs were settled, she moved to the city of Stettin (now known as Szczecin, Poland) where her younger sister and brother-in-law had moved after their marriage.

Women were barred from formally studying composition at most institutions of higher learning. The only option for most women who were interested in composing was private study with a tutor.

Carl Loewe

So she began taking private lessons from composer and conductor Carl Loewe, whose nickname was the “Schubert of North Germany.”

He was astonished by her natural ability, claiming that “such a God-given talent as hers had not been bestowed upon any other person he knew.”

He also famously commented: “You actually know nothing and everything at the same time! I shall be the gardener who grows your talent from a bud to a beautiful flower.”

The wording may have been patronising, but his heart was in the right place, as evidenced by the support and encouragement he gave her over the following years.

Studying with Loewe

During her apprenticeship with Loewe, she wrote her first two symphonies (No. 1 in C-minor and No. 2 in E-minor).

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 1

Because of his support and the support of the local music directors, Mayer had the opportunity to hear her orchestral works performed: an unusual opportunity for a woman composer of the era.

She incorporated what she learned into her next compositions for large ensembles.

She also began performing her chamber music at more and more private concerts and salons.

But there was only so much she could accomplish in Szczecin, and she became curious how far she could go if she relocated to a bigger city.

In 1847, on Loewe’s advice, she moved to Berlin – this time by herself, without any family.

Studying in Berlin

Adolf Bernard Marx

In Berlin, Emilie began studying fugue and double counterpoint with theorist and musicologist Adolf Bernard Marx.

Marx was a one-time friend of Felix Mendelssohn who had since feuded with him (and, in a fit of typically dramatic Romantic Era pique, destroyed their correspondence by throwing it into a river).

She also studied instrumentation with pioneering military bandmaster Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht.

Reviews of her scores soon began appearing in local music journals. At first, she submitted them under the name E. Mayer, where they were widely praised.

However, as soon as it became known that she was Emilie Mayer and not, say, Edward Mayer, reviewers’ attitudes grew more critical.

Publishing Her Music

Around this time, she set her mind on publishing her works.

To publish music in 1847 Berlin was a provocative step for a woman to take. Many women composers opted to keep their works private. To many, a woman publishing was seen as unseemly and immodest…as well as an implicit criticism of male relatives’ abilities to provide economically.

To grant perspective to Emilie’s decision, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’s family – also based in Berlin at the time – were notably cool on the idea of her publishing her works.

In 1846, the year before Mayer arrived in town, Hensel had gone against her family’s wishes and overseen the publication of a few of her hundreds of works.

In August 1846, Hensel wrote to a friend about pursuing publication:

I can truthfully say that I let it happen more than made it happen, and it is this in particular which cheers me… If [the publishers] want more from me, it should act as a stimulus to achieve. If the matter comes to an end, then I also won’t grieve, for I’m not ambitious.

Mayer, however, was ambitious. She was determined to “[make] it happen”…which it soon did.

Organising a Concert

Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, 1847

In the spring of 1850, Emilie began organising a concert consisting solely of her own works. The date was set for 21 April 1850.

The professional connections she’d been making paid off. Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, subsidised the costs of the performance and made free tickets available to the hand-picked audience.

The program ultimately included an overture, two symphonies, and her setting of Psalm 118 for chorus and orchestra, as well as chamber works including a string quartet and some works for solo piano.

Her teacher Wilhelm Wieprecht conducted.

Soon after, Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria, the Queen of Prussia, awarded her a gold medal of art.

The audience came away impressed. Famous critic Ludwig Rellstab wrote that her themes “flow smoothly through the securely defined realm of tonal colours, often with surprising elegance.”

A Blossoming Career

Over the following months, she would continue to organise concerts of her music. As a result, her output as a whole became increasingly acclaimed.

Her dramatic B-minor symphony, dating from 1851, with its bold Beethovenian gestures, became especially popular.

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 4

Loewe wrote of his student’s work, “The minor symphony by Miss Emilie Mayer is, in my deepest conviction, in any case an important and ingenious work of art with which the talented artist has enriched musical literature.”

Remarkably, Emilie would write a symphony annually during her time in Berlin, on top of her other compositions.

An International Career

Her productivity and self-promotion paid off. Soon her works were being performed in cities across Europe.

She traveled to Cologne, Munich, Leipzig, Halle, Brussels, Strasbourg, Dessau, and Lyon to oversee various performances.

She also became an honorary member of the Philharmonic Society in Munich, and, back home, started co-chairing the Berlin Opera Academy.

In 1856, she was invited by Archduchess Sophie, the mother of Emperor Franz Josef I, to perform her chamber music in Vienna, which she did. She was accompanied to Vienna by her brothers.

Lisztian Praise

Franz Liszt

Ever scrappy and resourceful, she kept up the momentum by writing to Franz Liszt, the most famous musical celebrity of his day, asking if he would be interested in transcribing her D-minor String Quintet for piano. (Savvily, she had dedicated the piece to him.)

Emilie Mayer: String Quintet in D major (a similar work)

He turned her down because he didn’t want to transcribe a string quintet for piano, but he praised the work:

I received your excellent quintet in D minor, which you are so kind to dedicate to me, only when I returned to Weimar these days, and therefore I would like to apologise for the delay in my sincere thanks to you.

Reading this work has given me a lot of interest – and I hope to hear even more[…]

The impossibility of reproducing orchestral works and especially string quartets with their indispensable sound and color on the dry piano has been with me for a long time of all arrangements – Attempts averted.

So do not misinterpret it, dear composer, when I [decline] your kindly wish, to transfer your quintets for the piano forte…

Returning to Szczecin and Her Roots

In 1861, at the age of forty-nine, she moved back to Szczecin.

We don’t know exactly why, but it may have been to be closer to her family, or possibly due to health reasons. In any case, she moved in with her brother and his family.

She still composed, but, having written eight symphonies, turned her attention to mastering chamber music.

Historians are still assembling her output, but it appears that she wrote at least…

- Seven violin sonatas

- Eleven cello sonatas

- Eight piano trios

- Two piano quartets

- Seven string quartets

- Two string quintets

- Eight symphonies

- Seven overtures

- One piano concerto

- One unfinished Singspiel opera, Die Fischerin

Some scores were lost in World War II when libraries were bombed.

However, the scores to many of these works (some of them still handwritten) are available on IMSLP for free here.

Return to Berlin and Later Life

In 1876, Mayer moved back to Berlin. As her comeback piece, she wrote and presented her Faust overture, inspired by Goethe.

The work was a major success and marked two decades of triumph in the music industry.

Emilie Mayer died in Berlin on 10 April 1883 from pneumonia, a few weeks before her seventy-first birthday. She was buried at the Holy Trinity Church near Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel and her brother Felix.

She died unmarried. Without a husband or children to carry on her legacy, many of her works fell into obscurity, despite their high quality and popularity.

Emilie Mayer’s grave

With the increased interest in women composers nowadays, more and more modern people are discovering her works. A series of wonderful recordings have been produced over the past few years. Hopefully, we will see her music on programs more and more in the seasons to come.

For further reading on Mayer, here is a link to “The Lieder of Emilie Mayer”, a research paper by Stephanie Sadownik.

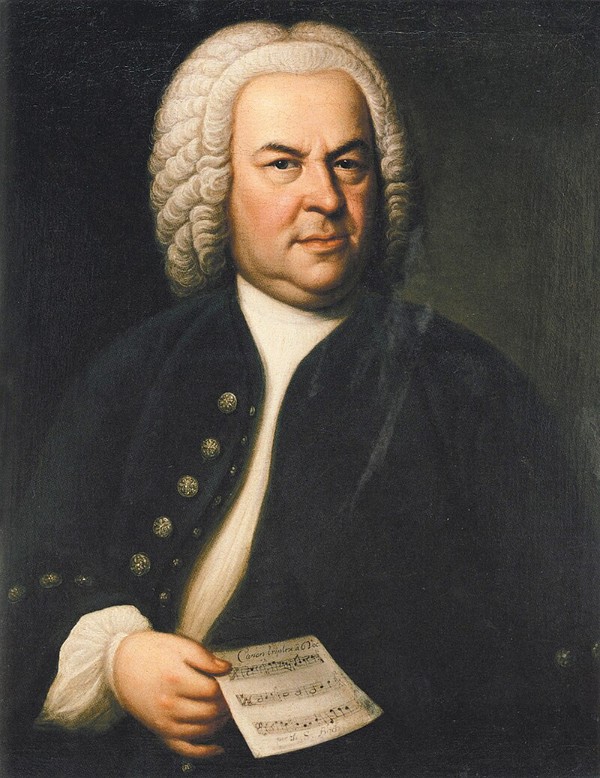

If You Like Bach, You Might Like Glenn Gould

by Georg Predota

Johann Sebastian Bach, the towering figure of Baroque music, is renowned for his intricate counterpoint, emotional depth, and technical brilliance. His compositions have inspired countless musicians and listeners for centuries.

Johann Sebastian Bach

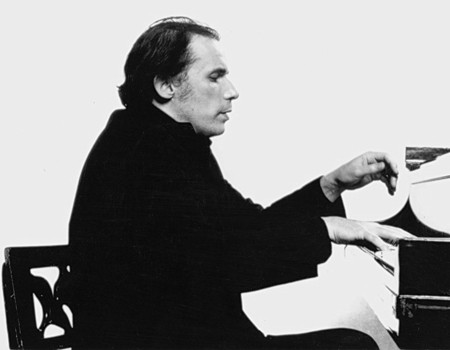

Among the interpreters of Bach’s keyboard music, few have left as indelible a mark as the Canadian pianist Glenn Gould. Known for his idiosyncratic and highly personal approach to Bach’s compositions, Gould’s performances offer a fresh lens through which to experience the composer’s genius.

Glenn Gould at the piano

Glenn Gould (1932–1982) was a singular voice in the interpretation of Bach, a pianist of extraordinary talent and polarising eccentricity. His approach to Bach was shaped by a combination of technical brilliance, intellectual rigour, and a willingness to challenge conventional performance practices.

A Fusion of Precision and Passion

Bach’s music is both intellectually stimulating and deeply emotive, balancing mathematical precision with profound spirituality. For the performer, they demand technical precision and interpretive insight, offering the artist a vast canvas for expression.

Bach’s mastery of counterpoint creates a dense, almost hypnotic interplay of lines that challenges both listener and performers. Structural complexity, emotional depth, and interpretive flexibility made Bach’s music a perfect vehicle for a performer like Glenn Gould, whose unorthodox approach brought a completely new dimension to these works.

Unlike most pianists of his time, who adhered to Romantic traditions of lush, expressive playing, Gould favoured clarity, precision, and a detached yet highly expressive style. His performances often emphasised the architectural logic of Bach’s music while infusing it with a distinctly modern sensibility.

A Revolutionary Blend

Glenn Gould

Gould’s 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations is perhaps the most iconic example of his approach. At the age of 22, Gould burst onto the international scene with his debut album for Columbia Records, which remains one of the most celebrated recordings of the work. In contrast to the stately, measured interpretations of earlier performers, Gould’s set is brisk, rhythmically incisive, and strikingly clear.

His tempos, particularly in the faster variations, are lightning-fast, showcasing his virtuosic control and ability to articulate each voice in Bach’s polyphony with crystalline precision. For instance, in Variation 7, a gigue-like movement, Gould’s buoyant rhythm and crisp articulation highlight the dance-like character, making the music feel alive and spontaneous.

Yet, Gould’s interpretation is not merely about speed or clarity. He brings a profound sense of individuality to the work, emphasising contrasts between variations and creating a narrative arc that feels both cohesive and unpredictable.

Eccentric Brilliance

Glenn Gould’s chair

Gould does engage in deliberate pacing and provides subtle dynamic shading that evokes a meditative intensity that resonates with Bach’s spiritual core. This ability to balance intellectual clarity with emotional expressiveness makes Gould’s Goldberg Variations a must-hear for Bach lovers, as it captures the composer’s multifaceted genius in a uniquely compelling way.

Gould’s interpretations are not without controversy, and this is part of what makes him so fascinating for Bach enthusiasts. His unconventional choices, such as extreme tempos, unconventional phrasing, and even his habit of humming along while playing, can be polarising.

Yet, these quirks often enhance the listener’s experience by offering a fresh perspective on familiar works by adding a layer of intimacy. While some find it distracting, others see it as a window into Gould’s immersion in the music and as a sign of his deep connection to Bach’s world. By bridging the intellectual and the emotional, Gould’s eccentricities can feel like an authentic expression of that duality.

Reimagining Bach

Glenn Gould

Gould’s engagement with Bach extended beyond his performances. As a writer, broadcaster, and thinker, he championed Bach’s music in ways that resonate with fans of the composer. In his essays and radio documentaries, he explored themes of solitude and creativity, drawing parallels to Bach’s introspective genius. His advocacy for Bach’s music as a timeless, universal language helped cement the composer’s place in the modern repertoire.

Gould’s choice to perform Bach on the modern piano reflects his belief in the music’s adaptability. By using the piano’s dynamic capabilities to bring out dramatic contrasts, Gould’s interpretation bridges historical and modern sensibilities.

Universal Genius

Gould’s interpretations are not just journeys into the composer’s world but also an encounter with a performer whose passion and originality mirror Bach’s own genius. His performances offer a gateway to experiencing the qualities of Bach’s music in a fresh and unforgettable way.

For Bach fans, Gould’s interpretations are not just performances. They are revelations that uncover the multifaceted beauty of Bach’s music. His unapologetic individuality makes his performances a natural extension of Bach’s own innovative spirit, and he invites listeners to rediscover the music through the lens of a singular artist.