Tomaso Albinoni

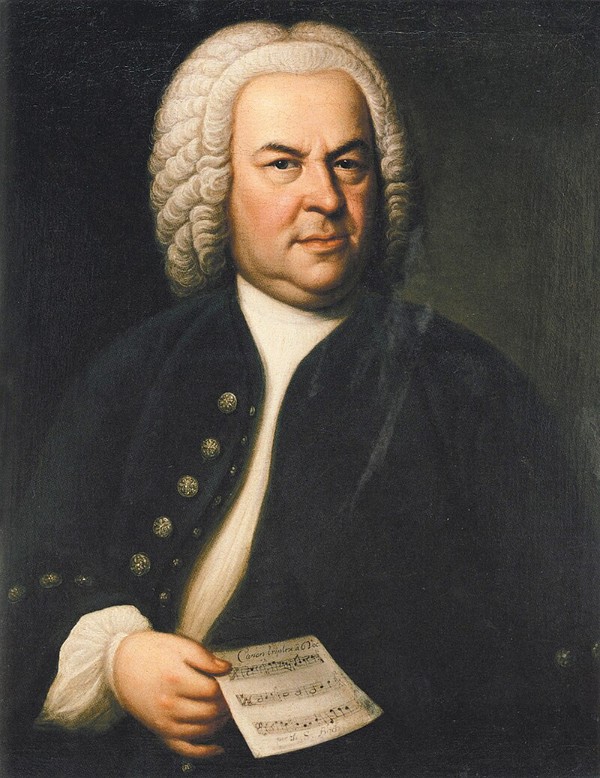

Tomaso Albinoni (1671-1750) and Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) were contemporaries, but they never actually met. While Albinoni was at home on various Italian and international operatic stages, Bach never traveled far away from his native community in North-Germany. We do know, however, that Bach did come in contact with the music of various Italian masters, and that his scholarly confrontation with these new styles decisively shaped his musical language and understanding. A scholar has suggested that “the best outside movements of Albinoni’s later concertos are remarkably like some of those by Bach, who benefited from the study of these works.” That similarity is found in some interesting variants of the common Albinoni approach to ritornello form, one, which Bach, took over into his works. Several movements from Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos “show clear signs of having been written under the influence of the concertos for one and two oboes of Albinoni’s Opus VII.”

The young Bach, Weimar, 1715

While we can certainly hear some of the similarities of structure and tonal organization, how did Bach actually got his hands on the Albinoni scores? Two possible scenarios have been suggested. In the autumn of 1717 Bach traveled from Weimar to Dresden. The crown prince of Saxony had recently returned from an extended journey to Italy, having spent almost one year in Venice. One of the musicians from the Dresden Court, Johann Georg Pisendel had accompanied the crown prince on his travels, and he became good friends with Vivaldi and Albinoni. Pisendel did make copies of Albinoni’s Op. VII and brought the music to Dresden. We might rightfully assume that the oboist of the Dresden Hofkapelle, Johann Christinan Richter took a close interest in these oboe concertos, and “Bach could certainly have come in contact with certain Albinoni concertos during his stay in Dresden.”

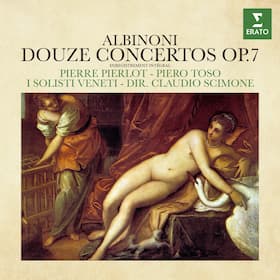

Albinoni’s Concertos Op. VII

We don’t know if Bach made copies of the works he encountered in Dresden, but we do know that he made a trip to Berlin 1719. He was on a mission to take delivery of a new harpsichord for court at Cöthen, and he spent much time and money buying the latest chamber works in circulation. “Albinoni’s Opus VII concertos may well have been among many acquisitions of printed music. There is no concrete source evidence, but it seems unlikely that Bach came in contact with the Albinoni collection much before the fall of 1717, given the collection’s relatively recent publication date and the rate of transmission of Amsterdam prints to Central Europe.”

The mature concertos of Albinoni “were an important factor in Bach’s approach to the genre throughout the decade of the 1720s. Albinoni was certainly not the only influence on Bach’s concertos from this period, but he must be counted among the chief influences. His extended opening ritornellos, his use of formal and structural elements derived from an Italianate vocal style of writing for the soloist seems to have greatly appealed to Bach.”

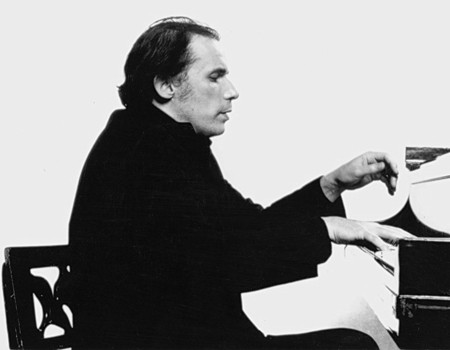

J.S. Bach: Fugue in C major, BWV 946

J.S. Bach: Fugue in A major, BWV 950

While the close connection between Albinoni’s Op. VII and Bach’s Brandenburg’s rely on careful stylistic, formal and harmonic analysis, an immediate connection is found in four keyboard fugues with subjects taken from Albinoni’s Op. 1. In BWV 946, 950, 951, 951a we find Bach mastering a new style and maturing as a composer. While some scholars find “facile note-spinning and pointless harmonic meandering among other weaknesses,” others “give Bach credit for tackling rhythmically difficult subjects in a variety of two-, three-, and four-part textures during his teenage years.” In BWV 950, Bach quotes directly from the Albinoni original at two points beyond the subject itself. However, Bach does not merely quote the passages but expands and transforms them to become pillars of the formal structure. A critic writes, “Bach’s scholarly engagement with Albinoni taught him to bring the fugue to a convincing conclusion without a thematically irrelevant coda.”