Emilie Mayer

Mayer’s symphonies, chamber music, and piano works stand as testaments to both her talent and her determination to succeed in a male-dominated world.

Today, we’re looking at her gripping biography and how she made a hugely successful career for herself in her middle age, after enduring unimaginably painful personal loss.

Emilie Mayer’s Family

Emilie Mayer was born Emilie Luise Friderica Mayer on 14 May 1812. She was the third of five children and the eldest daughter.

The Mayers lived in the German town of Friedland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, roughly seventy kilometers from the Baltic Sea, where her father worked as an apothecary.

Tragedy struck the family a few years after Emilie’s birth, when her mother died. After her mother’s death, Emilie would have been expected to play the role of matriarch within the immediate family.

This may have been one reason why she never married…and one reason why she felt freer to become a composer.

Emilie Mayer’s Early Education

Emilie Mayer

It is believed that Emilie’s education was overseen by private tutors, as the local Latin school only accepted boys.

She began piano lessons at the age of five with a local organist named Carl Heinrich Ernst Driver.

She later wrote modestly, “After a few lessons… I composed variations, dances, little rondos, etc.” Driver was amused by his student’s precocity and helped notate these works for her.

Her father was thrilled by his daughter’s musical talent and supported her studies throughout her childhood.

Unexpected Tragedy Changes Everything

The defining event of Emilie’s life occurred in 1840, on the twenty-sixth anniversary of her mother’s burial, when her father shot and killed himself.

She dealt with her shock and grief by throwing herself into composing. But tragically, she suffered another major blow a few months later, when her teacher, Driver, also died.

Emilie was fast approaching thirty, without the economic protection a nineteenth-century husband would provide. Suddenly, she had to figure out what to do with the rest of her life, and how to make a living – and fast.

She decided to devote herself to music. Fortunately, her brothers supported the decision.

Moving to Szczecin

After her father’s affairs were settled, she moved to the city of Stettin (now known as Szczecin, Poland) where her younger sister and brother-in-law had moved after their marriage.

Women were barred from formally studying composition at most institutions of higher learning. The only option for most women who were interested in composing was private study with a tutor.

Carl Loewe

So she began taking private lessons from composer and conductor Carl Loewe, whose nickname was the “Schubert of North Germany.”

He was astonished by her natural ability, claiming that “such a God-given talent as hers had not been bestowed upon any other person he knew.”

He also famously commented: “You actually know nothing and everything at the same time! I shall be the gardener who grows your talent from a bud to a beautiful flower.”

The wording may have been patronising, but his heart was in the right place, as evidenced by the support and encouragement he gave her over the following years.

Studying with Loewe

During her apprenticeship with Loewe, she wrote her first two symphonies (No. 1 in C-minor and No. 2 in E-minor).

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 1

Because of his support and the support of the local music directors, Mayer had the opportunity to hear her orchestral works performed: an unusual opportunity for a woman composer of the era.

She incorporated what she learned into her next compositions for large ensembles.

She also began performing her chamber music at more and more private concerts and salons.

But there was only so much she could accomplish in Szczecin, and she became curious how far she could go if she relocated to a bigger city.

In 1847, on Loewe’s advice, she moved to Berlin – this time by herself, without any family.

Studying in Berlin

Adolf Bernard Marx

In Berlin, Emilie began studying fugue and double counterpoint with theorist and musicologist Adolf Bernard Marx.

Marx was a one-time friend of Felix Mendelssohn who had since feuded with him (and, in a fit of typically dramatic Romantic Era pique, destroyed their correspondence by throwing it into a river).

She also studied instrumentation with pioneering military bandmaster Wilhelm Friedrich Wieprecht.

Reviews of her scores soon began appearing in local music journals. At first, she submitted them under the name E. Mayer, where they were widely praised.

However, as soon as it became known that she was Emilie Mayer and not, say, Edward Mayer, reviewers’ attitudes grew more critical.

Publishing Her Music

Around this time, she set her mind on publishing her works.

To publish music in 1847 Berlin was a provocative step for a woman to take. Many women composers opted to keep their works private. To many, a woman publishing was seen as unseemly and immodest…as well as an implicit criticism of male relatives’ abilities to provide economically.

To grant perspective to Emilie’s decision, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’s family – also based in Berlin at the time – were notably cool on the idea of her publishing her works.

In 1846, the year before Mayer arrived in town, Hensel had gone against her family’s wishes and overseen the publication of a few of her hundreds of works.

In August 1846, Hensel wrote to a friend about pursuing publication:

I can truthfully say that I let it happen more than made it happen, and it is this in particular which cheers me… If [the publishers] want more from me, it should act as a stimulus to achieve. If the matter comes to an end, then I also won’t grieve, for I’m not ambitious.

Mayer, however, was ambitious. She was determined to “[make] it happen”…which it soon did.

Organising a Concert

Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, 1847

In the spring of 1850, Emilie began organising a concert consisting solely of her own works. The date was set for 21 April 1850.

The professional connections she’d been making paid off. Friedrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia, subsidised the costs of the performance and made free tickets available to the hand-picked audience.

The program ultimately included an overture, two symphonies, and her setting of Psalm 118 for chorus and orchestra, as well as chamber works including a string quartet and some works for solo piano.

Her teacher Wilhelm Wieprecht conducted.

Soon after, Elisabeth Ludovika of Bavaria, the Queen of Prussia, awarded her a gold medal of art.

The audience came away impressed. Famous critic Ludwig Rellstab wrote that her themes “flow smoothly through the securely defined realm of tonal colours, often with surprising elegance.”

A Blossoming Career

Over the following months, she would continue to organise concerts of her music. As a result, her output as a whole became increasingly acclaimed.

Her dramatic B-minor symphony, dating from 1851, with its bold Beethovenian gestures, became especially popular.

Emilie Mayer’s Symphony No. 4

Loewe wrote of his student’s work, “The minor symphony by Miss Emilie Mayer is, in my deepest conviction, in any case an important and ingenious work of art with which the talented artist has enriched musical literature.”

Remarkably, Emilie would write a symphony annually during her time in Berlin, on top of her other compositions.

An International Career

Her productivity and self-promotion paid off. Soon her works were being performed in cities across Europe.

She traveled to Cologne, Munich, Leipzig, Halle, Brussels, Strasbourg, Dessau, and Lyon to oversee various performances.

She also became an honorary member of the Philharmonic Society in Munich, and, back home, started co-chairing the Berlin Opera Academy.

In 1856, she was invited by Archduchess Sophie, the mother of Emperor Franz Josef I, to perform her chamber music in Vienna, which she did. She was accompanied to Vienna by her brothers.

Lisztian Praise

Franz Liszt

Ever scrappy and resourceful, she kept up the momentum by writing to Franz Liszt, the most famous musical celebrity of his day, asking if he would be interested in transcribing her D-minor String Quintet for piano. (Savvily, she had dedicated the piece to him.)

Emilie Mayer: String Quintet in D major (a similar work)

He turned her down because he didn’t want to transcribe a string quintet for piano, but he praised the work:

I received your excellent quintet in D minor, which you are so kind to dedicate to me, only when I returned to Weimar these days, and therefore I would like to apologise for the delay in my sincere thanks to you.

Reading this work has given me a lot of interest – and I hope to hear even more[…]

The impossibility of reproducing orchestral works and especially string quartets with their indispensable sound and color on the dry piano has been with me for a long time of all arrangements – Attempts averted.

So do not misinterpret it, dear composer, when I [decline] your kindly wish, to transfer your quintets for the piano forte…

Returning to Szczecin and Her Roots

In 1861, at the age of forty-nine, she moved back to Szczecin.

We don’t know exactly why, but it may have been to be closer to her family, or possibly due to health reasons. In any case, she moved in with her brother and his family.

She still composed, but, having written eight symphonies, turned her attention to mastering chamber music.

Historians are still assembling her output, but it appears that she wrote at least…

- Seven violin sonatas

- Eleven cello sonatas

- Eight piano trios

- Two piano quartets

- Seven string quartets

- Two string quintets

- Eight symphonies

- Seven overtures

- One piano concerto

- One unfinished Singspiel opera, Die Fischerin

Some scores were lost in World War II when libraries were bombed.

However, the scores to many of these works (some of them still handwritten) are available on IMSLP for free here.

Return to Berlin and Later Life

In 1876, Mayer moved back to Berlin. As her comeback piece, she wrote and presented her Faust overture, inspired by Goethe.

The work was a major success and marked two decades of triumph in the music industry.

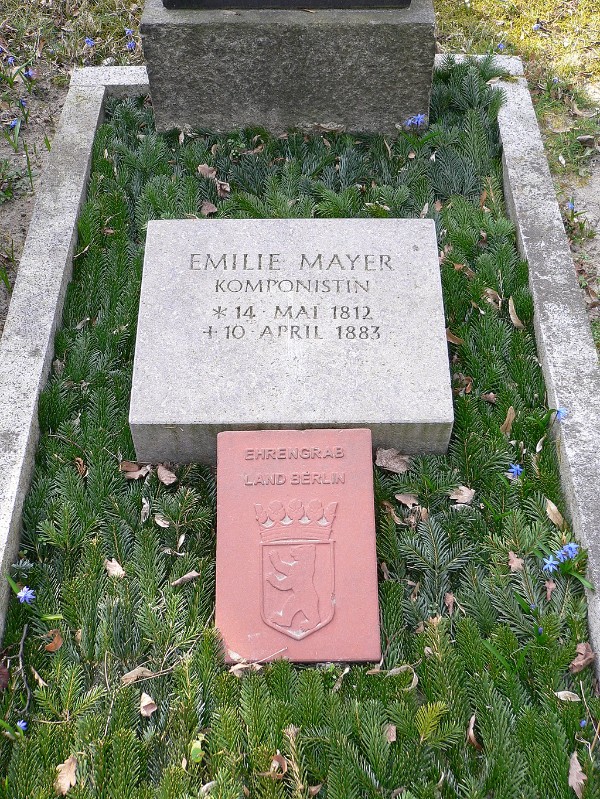

Emilie Mayer died in Berlin on 10 April 1883 from pneumonia, a few weeks before her seventy-first birthday. She was buried at the Holy Trinity Church near Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel and her brother Felix.

She died unmarried. Without a husband or children to carry on her legacy, many of her works fell into obscurity, despite their high quality and popularity.

Emilie Mayer’s grave

With the increased interest in women composers nowadays, more and more modern people are discovering her works. A series of wonderful recordings have been produced over the past few years. Hopefully, we will see her music on programs more and more in the seasons to come.

For further reading on Mayer, here is a link to “The Lieder of Emilie Mayer”, a research paper by Stephanie Sadownik.