It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, January 16, 2026

New English Orchestral Music: David Matthews

by Maureen Buja January 12th, 2026

David Matthews’s opera Anna

Anna, the opera, looks at the personal implications of the 1989 revolutions in Central Europe. Whole countries were freed, but when the countries started looking at how the previous regimes were so successful, stories of betrayal and bravery stood side-by-side. Anna and her brother Peter are orphans. When Anna falls in love with Miro, he eventually must tell them that it was his work with the secret police that caused their father’s arrest and subsequent death. Anna wishes to forgive him, but Peter confronts Miro with a gun, and, in the ensuing struggle, it is Anna who is killed. The death unites the two men, and the opera ends in a general chorus for forgiveness. The ending lines of the chorus: ‘She paid the price of our bitterness. For love of her, we must forgive’, could be true in so many situations today.

The orchestral reduction consists of a diptych: Anna in Love and Lament for Anna, starting with her emotional happiness and ending with the two men’s realisation that they have killed the one person they both loved.

Matthews was encouraged to make his Anna reduction by Jac van Steen, the conductor of The Grange Hampshire performance, following the example of Richard Strauss and his own reductions of Intermezzo and Die Frau ohne Schatten.

David Matthews

The single-movement Symphony No. 11, Op. 168 follows. The composer says it was inspired by such diverse things as Schoenberg’s First String Quartet and Sibelius’ Symphony No. 7, a trumpet player he heard at a festival in 2022, and Lord of the Rings’ description of the woods of Lórien. There are calls to battle and a chaconne; the horn of Rohan has a part as well.

The final work on the recording is his Flute Concerto, Op. 166. It rests on the melodic aspect of the flute, and the composer says, ‘My Concerto alternates between song and dance’. He uses a small ‘Haydn-sized’ orchestra (strings plus 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, and 2 horns), and takes a page from Nielsen’s Flute concerto and the comments that its first movement ‘spends all its time looking for a key’. Accordingly, the movement begins in E flat major and moves through a descending line of F, G, A, B flat, C, D before returning to E flat major for the recapitulation. The coda starts the key search again, and the movement ends in D major. The flute line throughout is glorious.

David Matthews: Flute Concerto, Op. 166 – I. Allegretto

Movement II, Lento, moves down a half step and starts in D flat major. The slower outer sections frame a quicker allegretto middle section, which I thought of as a dance to celebrate Pan with panpipes, and which is mostly pentatonic.

The final movement, with a somewhat Irish flavour, is based on a melody the composer wrote for his wife, Jennifer, for Christmas in 2016. More dances liven the movement.

The music is filled with a wealth of invention and successfully integrates the modern lack of a tonal centre with traditional forms and constructs. In the Symphony No. 11, the recapitulation section does land us back at our starting key of E flat major, but that is not the key destined to end the piece; it is, however, the key that ends the last piece on the recording, to bring everything around full circle. Matthews’ music, in this expansive presentation by the Ulster Orchestra, brings us a composer we may not have been familiar with and gives us the opportunity to hear parts of his recent opera.

David Matthews: Anna: Symphonic Diptych; Symphony No. 11, Flute Concerto

Emma Halnan (flute); Ulster Orchestra; Jac van Steen (conductor)

SOMM Recordings: SOMMCD 0710

Release date: 17 October 2025

Official Website

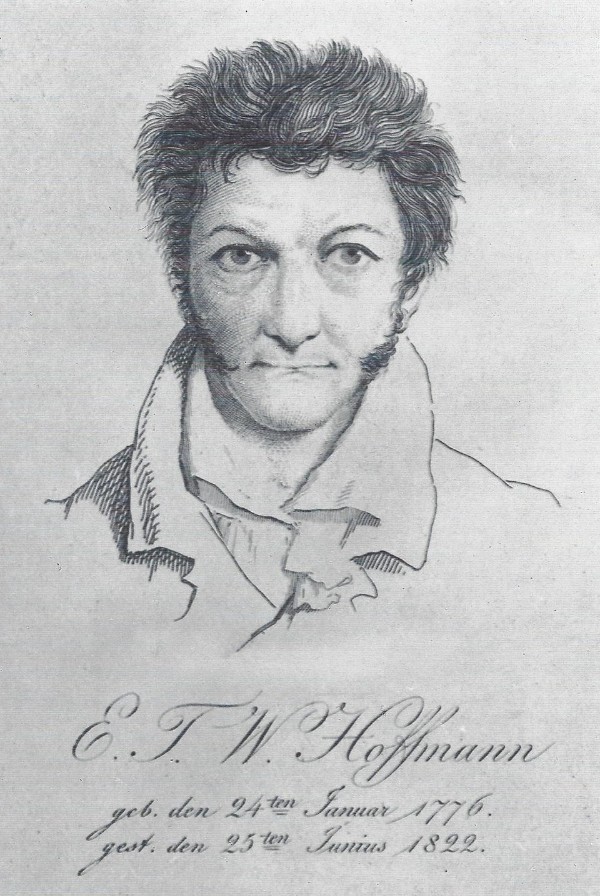

E.T.A. Hoffmann at 250 (Born on January 24, 1776)

On 24 January, we mark the birth of one of the most remarkable figures of the German Romantic era. Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann (1776–1822), better known by his pen name, E.T.A. Hoffmann is known as the master of the fantastic and supernatural in literature.

However, Hoffmann was far more than a storyteller. He was a true artistic polymath, an accomplished composer, music critic, and visual artist whose life and work exemplify the Romantic fascination with the intersection of imagination, emotion, and intellect.

E.T.A. Hoffmann

As J. Zipes notes, “his fantastic tales epitomize the Romantic fascination with the supernatural and the expressively distorted or exaggerated.”

On the occasion of his 250th birthday, let’s explore the life, art, and the enduring legacy of a man whose creative ambitions spilled across multiple disciplines.

E.T.A. Hoffmann: Sonata in A Major, “Andante”

Between Law Books and Lyres

Hoffmann was born in Königsberg, present-day Kaliningrad, into a family of jurists. His early education was shaped by his uncle Otto Doerffer, described as “an unimaginative, mechanical and strict disciplinarian.”

Although Hoffmann was obliged to study law, he pursued music and painting with equal vigour. He studied piano with Carl Gottlieb Richter, thoroughbass and counterpoint with the Königsberg organist Christian Wilhelm Podbielski, and violin with choirmaster Christian Otto Gladau.

These early studies laid the foundation for his later career as a composer and music critic. Hoffmann completed his law degree in 1795 and took up a clerical position in Berlin. Yet, even as a young lawyer, his life was saturated with artistic engagement.

He attended Italian operas, composed piano pieces, and studied composition under J.F. Reichardt. His first operetta, The Mask, was even sent to Queen Luise of Prussia, reflecting Hoffmann’s early ambition to intertwine his legal career with a public artistic presence.

Setbacks, Satire, and Survival

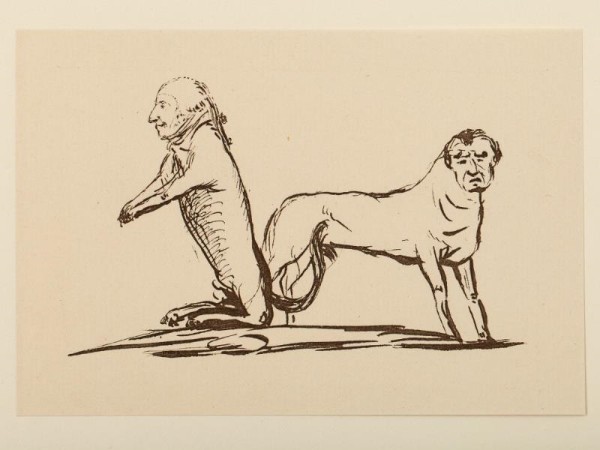

Drawing by E.T.A. Hoffmann

Hoffmann’s career was far from linear. After passing his final law examinations, he was appointed assistant judge at the high court in Posen. However, his boldness and wit sometimes landed him in trouble. Hoffmann drew caricatures of military authorities in the Posen garrison, and as a result, he was exiled to southern Prussia.

During this period, he struggled to have his compositions performed publicly. Several of his piano works submitted to publishers, including Nägeli and Schott, were rejected, and his comedic play The Prize, written for a literary competition, won only the judges’ commendation, not the prize money.

Despite these setbacks, Hoffmann’s musical ambitions persisted, and in 1804 he was transferred to Warsaw. There, he rebuilt his career from the ground up, conducting, performing, and composing. Within a year, he had an opera successfully staged, completed a D-minor Mass, and published a piano sonata in a Polish music magazine.

Hoffmann’s refusal to submit to Napoleon’s authority when the French entered Warsaw led to his expulsion, but he eventually settled in Berlin and later became music director at the theatre in Bamberg, as well as a music critic for the influential Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung in Leipzig.

E.T.A. Hoffmann: Mass in D Minor, AV 18 – Kyrie (Jutta Böhnert, soprano; Rebecca Martin, mezzo-soprano; Thomas Cooley, tenor; Yorck Felix Speer, bass; Cologne West German Radio Chorus; Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra; Rupert Huber, cond.)

Where Imagination Meets Longing

E.T.A. Hoffmann

Hoffmann’s literary breakthrough came in 1809 with the publication of Ritter Gluck, a story about a man who believes he has met the composer Christoph Willibald Gluck decades after Gluck’s death. This story, like much of Hoffmann’s work, highlights the Romantic fascination with the supernatural and the interplay between reality and imagination.

Throughout his life, Hoffmann’s literary endeavours were deeply intertwined with his personal experiences. Scholars have noted that “the mastering of unfulfilled passion remained Hoffmann’s poetic mission to the end of his life.”

He himself hinted at the close connection between his “hopeless love for his young pupil Julia Mark, the crucial experience of his Bamberg years, and the impetus of his literary production.”

His collection Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier, as well as the tales of Johannes Kreisler and Don Juan, were instant literary successes, cementing Hoffmann’s reputation as a writer of uncanny and psychologically complex stories.

Sounding the Fantastic

Yet literature was only one aspect of Hoffmann’s creativity. He also pursued music with vigour, composing operas, symphonies, piano sonatas, and chamber music. His opera Undine, premiered in 1816, exemplifies his musical style and dramatic sensibility.

Carl Maria von Weber praised the opera for its “swift pace and forward-pressing dramatic action” and admired Hoffmann’s restraint in avoiding “excessive and inapt melodic decoration.”

Unfortunately, after the 14th performance, the Königliches Schauspielhaus in Berlin burned down, and Undine was never staged again during Hoffmann’s lifetime. Nevertheless, his music continued to influence generations of composers, most notably Robert Schumann.

Hoffmann was central to Schumann’s Romantic aesthetic. He even borrowed titles from Hoffmann’s works for his compositions, including Fantasiestücke, Nachtstücke, and Kreisleriana.

The Unity of the Arts

Memorial to E.T.A. Hoffmann, 2014 © Leopold Röhrer

Hoffmann’s dual identity as a writer and musician reflects his belief in the unity of the arts. He considered composition and literary creation equally vital, and he understood music as a deeply Romantic form capable of expressing the ineffable.

His writings on Beethoven, particularly the Fifth Symphony, urged readers and fellow writers to regard music as the most Romantic of all arts. Hoffmann’s music criticism was sharp, insightful, and often provocative, demonstrating his profound understanding of harmony, structure, and expressive power.

He treated music not merely as entertainment but as a vehicle for imagination and emotion, prefiguring later Romantic thought on the synthesis of music and literature.

Brief Life, Long Shadow

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s satirical drawing

Hoffmann also left a mark as a visual artist, producing sketches and caricatures that captured both humour and social commentary. These visual works reveal a playful, observant mind and an enduring engagement with the human condition.

In this sense, Hoffmann embodied the Romantic ideal of the polymath, pursuing excellence in multiple artistic domains, all while navigating the challenges of a professional life constrained by law, politics, and censorship.

Despite his wide-ranging talents, Hoffmann’s life was marked by personal struggles and early death. He fought bureaucracy, suffered unrequited loves, and contended with financial instability throughout his career.

His life ended tragically in 1822 when he died of syphilis at the age of 46. Yet his legacy has only grown in the two centuries since his death. Today, Hoffmann is celebrated not only as a foundational figure of Romantic literature but also as a pioneer in music criticism and a creator of enduring works in multiple media.

Hearing Hoffmann Anew

Hoffmann’s music is increasingly appreciated alongside his literary achievements. His Piano Trio in E Major and Keyboard Sonata in C-sharp minor are fine examples of early Romantic chamber music, combining lyricism with structural inventiveness.

His Symphony in E-flat Major demonstrates his skill in orchestral writing and his sensitivity to dramatic pacing, qualities that mirrored his literary narrative techniques. Hoffmann’s compositions are characterised by both technical mastery and an imaginative, sometimes whimsical, sensibility that parallels the fantastic worlds of his stories.

The Afterlife of Imagination

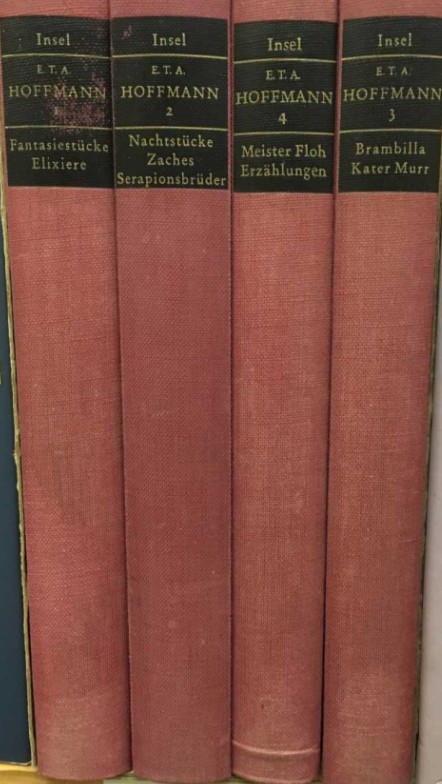

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s 4 volume set

The influence of E.T.A. Hoffmann extends well beyond his own era. Writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Mary Shelley absorbed elements of his fantastic and psychologically complex tales, while composers like Schumann, Chopin, and Mendelssohn drew inspiration from the narrative structures and expressive intensity of his music criticism.

Hoffmann’s insistence on the importance of imagination, emotion, and artistic integrity continues to resonate today. His works remind us that creativity is often most powerful when it crosses the boundaries between genres, disciplines, and even the ordinary and the supernatural.

On January 24, as we mark the anniversary of Hoffmann’s birth, it is fitting to revisit his music, his tales, and his art. His life was short, but his vision was vast, and his influence continues to shape the landscape of literature and music alike.

Hoffmann’s legacy encourages us to pursue our own creative ambitions with the same fearless curiosity, artistic ambition, and devotion to imagination that defined his extraordinary life.

Potpourri: Melodies in Medley

by Fanny Po Sim Head January 10th, 2026

© opera-diary.com

The potpourri appeared prominently in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, during a time when opera melodies circulated well beyond the theatre. Before recordings, audiences encountered favourite tunes through arrangements for salon performances, home music-making, and public concerts. Potpourris fulfilled a desire for musical recognition while allowing composers and performers to create new works that were both accessible and marketable. Unlike sonata-based forms, potpourris generally avoid motivic development. Instead, they feature a sequence of recognisable melodies, often linked by brief transitions and framed by a dramatic introduction and a virtuosic conclusion. This adaptable structure made the genre perfect for showcasing performers’ technical skills while ensuring immediate audience engagement.

Louis Spohr

The early nineteenth century saw a flourishing of potpourris written for solo instruments with orchestra or chamber ensemble, frequently by composer-performers themselves. Louis Spohr’s Potpourri for Clarinet and Orchestra on Themes by von Winter in F major, Op. 80 exemplifies the genre’s elegance and balance. Drawing on melodies from Peter von Winter’s opera Das unterbrochene Opferfest (The Interrupted Sacrifice, 1811), Spohr transforms operatic arias into a clarinet showcase emphasising lyricism, agility, and expressive refinement.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel, 1814

Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Potpourri, Op. 94 (Fantasie) for Viola and Orchestra occupies a distinctive position in the repertoire. At a time when the viola was rarely featured as a solo instrument, Hummel uses the potpourri format to showcase the instrument’s warmth and agility without the formal weight of a concerto, demonstrating the genre’s adaptability. The work is also one of the earliest substantial pieces written specifically for viola solo with orchestral accompaniment, highlighting the instrument’s lyrical and virtuosic potential in a concert setting. It draws much of its melodic material from well-known opera themes by Mozart, particularly from Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and The Abduction from the Seraglio, as well as from Rossini’s Tancredi. These familiar tunes are framed by newly composed introduction and finale sections, allowing Hummel to combine recognizability with virtuosic invention in a format characteristic of early nineteenth-century potpourri traditions.

Mauro Giuliani: Grand Potpourri Op.53 for Flute and Guitar

The potpourri also thrived in more intimate chamber settings. Mauro Giuliani’s Grand Potpourri, Op. 53 for Flute and Guitar reflects the vibrant salon culture of early nineteenth-century Vienna. Drawing on popular operatic melodies, the work unfolds as a dialogue between flute and guitar, with the flute carrying lyrical and decorative lines. In contrast, the guitar provides harmonic grounding and idiomatic figurations. Giuliani’s potpourri demonstrates how the genre could function effectively beyond orchestral contexts, appealing to audiences seeking refinement, intimacy, and melodic familiarity.

Arthur Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan’s operetta overtures exemplify potpourri practice, particularly in the overtures to H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado. These works present a sequence of the operetta’s main melodies with minimal thematic development, linked by brief transitions. The overture to The Pirates of Penzance (1879), largely orchestrated by Alfred Cellier under tight deadlines, strings together well-known tunes such as “Pour, O Pour the Pirate Sherry,” “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General,” and “With Cat-Like Tread,” alternating lively comic passages with lyrical themes. Functioning as musical previews, these overtures rely on audience recognition and contrast, aligning closely with nineteenth-century potpourri tradition. In Sullivan’s hands, the potpourri becomes a theatrical device that shapes audience expectations while showcasing orchestral color, inventive instrumentation, and melodic wit.

The potpourri flourished equally in dance and domestic contexts. Johann Strauss II’s Potpourri Quadrille reflects Vienna’s vibrant ballroom culture, in which popular tunes were repurposed for social dancing. These works blurred the boundary between popular entertainment and compositional craft. For keyboard music, Karol Kazimierz Kurpinski’s Potpourri or Variations on Various National Themes, composed for the seven-year-old pianist Józef Krogulski and published in 1813, blends classical form with Polish folk and dance elements. Its sections include a Poco adagio introduction, a lyrical Dumka, a stately polonaise (Alla polacca), a brief Krakowiak, and a virtuosic Mazur. The work exploits the piano’s full range of techniques while reflecting Kurpiński’s melodic inventiveness and commitment to Polish national style, making it both a virtuosic showcase and a culturally distinctive potpourri.

Franz Liszt’s Réminiscences de Norma, S. 394

By the mid-nineteenth century, distinctions between potpourri, fantasy, and paraphrase became increasingly fluid. At its core, a potpourri presents a succession of recognizable melodies with minimal transformation. A fantasy typically offers greater freedom of form and more extensive thematic elaboration, while a paraphrase implies substantial recomposition, integrating operatic material into a newly conceived musical structure. Franz Liszt’s Réminiscences, including Réminiscences de Don Juan, Norma, and Lucia di Lammermoor, represent the most ambitious evolution of the potpourri principle. Liszt assembles multiple operatic numbers into large-scale concert works, subjecting them to dramatic transformation, contrapuntal treatment, and symphonic pacing. Familiar melodies become vehicles for structural unity and expressive depth, transcending the genre’s earlier entertainment-driven aims.

Henry Grevedon: Sigismond Thalberg, 1836 (Gallica, btv1b8425259g)

Sigismond Thalberg’s Grande Fantaisie sur Moïse de Rossini, Op.33, offers a more restrained but highly influential model. While the work features a potpourri-like collection of operatic themes, Thalberg unifies them through lyrical flow and his famous “three-hand effect,” showcasing the refined elegance of mid-century salon culture.

In the violin repertoire, Henryk Wieniawski’s Fantaisie brillante sur des thèmes de Faust shows how potpourri principles extended beyond the piano. Drawing from Gounod’s opera, Wieniawski links well-known melodies within a structure that remains essentially potpourri-based, yet transforms each theme into a display for virtuosity and expressive flair.

By the twentieth century, the potpourri had largely fallen out of favour and was often associated with nostalgia or light entertainment. Nevertheless, some composers continued to engage with its collage-like principles in more reflective and stylistically complex ways. Ernst Krenek’s Potpourri, Op. 54 for Symphony Orchestra (1927) reimagines the genre within a modernist framework, employing fragmentation, sharp contrasts, and stylistic juxtaposition to evoke musical memory and historical continuity rather than simple melodic recognition.

R. Strauss: Die schweigsame Frau – Potpourri, Op.80 (1935)

A similarly late but highly sophisticated rethinking of the genre appears in Richard Strauss’s Die schweigsame Frau – Potpourri, Op. 80 (1935). Drawn from his comic opera Die schweigsame Frau, with a libretto by Stefan Zweig based on Ben Jonson’s Epicoene, the work assembles the opera’s principal themes into a continuous orchestral concert piece. Unlike nineteenth-century potpourris that prioritise immediate familiarity and lightness, Strauss’s treatment is symphonic in scope, with dense orchestration, harmonic complexity, and fluid transitions characteristic of his mature style. While the piece still functions as a concert synopsis of the opera, it simultaneously showcases Strauss’s mastery of orchestral colour, rhythmic vitality, and ironic wit.

Although often marginalised in narratives of “serious” music, the potpourri played a central role in nineteenth-century musical life. It shaped how audiences encountered opera outside the theatre, fueled the rise of instrumental virtuosity, and connected public concert culture with salon and domestic music-making. From Spohr, Hummel, and Giuliani to Sullivan, Strauss, Liszt, Thalberg, and Wieniawski, and finally to Krenek and Richard Strauss, the potpourri emerges not as a peripheral curiosity but as a flexible and enduring practice, one that continually adapted to changing tastes, performance contexts, and aesthetic priorities.