© opera-diary.com

The potpourri appeared prominently in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, during a time when opera melodies circulated well beyond the theatre. Before recordings, audiences encountered favourite tunes through arrangements for salon performances, home music-making, and public concerts. Potpourris fulfilled a desire for musical recognition while allowing composers and performers to create new works that were both accessible and marketable. Unlike sonata-based forms, potpourris generally avoid motivic development. Instead, they feature a sequence of recognisable melodies, often linked by brief transitions and framed by a dramatic introduction and a virtuosic conclusion. This adaptable structure made the genre perfect for showcasing performers’ technical skills while ensuring immediate audience engagement.

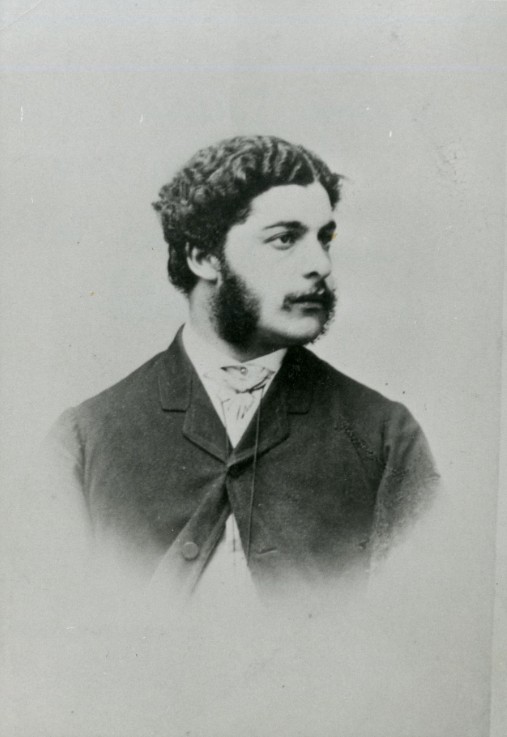

Louis Spohr

The early nineteenth century saw a flourishing of potpourris written for solo instruments with orchestra or chamber ensemble, frequently by composer-performers themselves. Louis Spohr’s Potpourri for Clarinet and Orchestra on Themes by von Winter in F major, Op. 80 exemplifies the genre’s elegance and balance. Drawing on melodies from Peter von Winter’s opera Das unterbrochene Opferfest (The Interrupted Sacrifice, 1811), Spohr transforms operatic arias into a clarinet showcase emphasising lyricism, agility, and expressive refinement.

Johann Nepomuk Hummel, 1814

Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Potpourri, Op. 94 (Fantasie) for Viola and Orchestra occupies a distinctive position in the repertoire. At a time when the viola was rarely featured as a solo instrument, Hummel uses the potpourri format to showcase the instrument’s warmth and agility without the formal weight of a concerto, demonstrating the genre’s adaptability. The work is also one of the earliest substantial pieces written specifically for viola solo with orchestral accompaniment, highlighting the instrument’s lyrical and virtuosic potential in a concert setting. It draws much of its melodic material from well-known opera themes by Mozart, particularly from Don Giovanni, The Marriage of Figaro, and The Abduction from the Seraglio, as well as from Rossini’s Tancredi. These familiar tunes are framed by newly composed introduction and finale sections, allowing Hummel to combine recognizability with virtuosic invention in a format characteristic of early nineteenth-century potpourri traditions.

Mauro Giuliani: Grand Potpourri Op.53 for Flute and Guitar

The potpourri also thrived in more intimate chamber settings. Mauro Giuliani’s Grand Potpourri, Op. 53 for Flute and Guitar reflects the vibrant salon culture of early nineteenth-century Vienna. Drawing on popular operatic melodies, the work unfolds as a dialogue between flute and guitar, with the flute carrying lyrical and decorative lines. In contrast, the guitar provides harmonic grounding and idiomatic figurations. Giuliani’s potpourri demonstrates how the genre could function effectively beyond orchestral contexts, appealing to audiences seeking refinement, intimacy, and melodic familiarity.

Arthur Sullivan

Arthur Sullivan’s operetta overtures exemplify potpourri practice, particularly in the overtures to H.M.S. Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, and The Mikado. These works present a sequence of the operetta’s main melodies with minimal thematic development, linked by brief transitions. The overture to The Pirates of Penzance (1879), largely orchestrated by Alfred Cellier under tight deadlines, strings together well-known tunes such as “Pour, O Pour the Pirate Sherry,” “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major-General,” and “With Cat-Like Tread,” alternating lively comic passages with lyrical themes. Functioning as musical previews, these overtures rely on audience recognition and contrast, aligning closely with nineteenth-century potpourri tradition. In Sullivan’s hands, the potpourri becomes a theatrical device that shapes audience expectations while showcasing orchestral color, inventive instrumentation, and melodic wit.

The potpourri flourished equally in dance and domestic contexts. Johann Strauss II’s Potpourri Quadrille reflects Vienna’s vibrant ballroom culture, in which popular tunes were repurposed for social dancing. These works blurred the boundary between popular entertainment and compositional craft. For keyboard music, Karol Kazimierz Kurpinski’s Potpourri or Variations on Various National Themes, composed for the seven-year-old pianist Józef Krogulski and published in 1813, blends classical form with Polish folk and dance elements. Its sections include a Poco adagio introduction, a lyrical Dumka, a stately polonaise (Alla polacca), a brief Krakowiak, and a virtuosic Mazur. The work exploits the piano’s full range of techniques while reflecting Kurpiński’s melodic inventiveness and commitment to Polish national style, making it both a virtuosic showcase and a culturally distinctive potpourri.

Franz Liszt’s Réminiscences de Norma, S. 394

By the mid-nineteenth century, distinctions between potpourri, fantasy, and paraphrase became increasingly fluid. At its core, a potpourri presents a succession of recognizable melodies with minimal transformation. A fantasy typically offers greater freedom of form and more extensive thematic elaboration, while a paraphrase implies substantial recomposition, integrating operatic material into a newly conceived musical structure. Franz Liszt’s Réminiscences, including Réminiscences de Don Juan, Norma, and Lucia di Lammermoor, represent the most ambitious evolution of the potpourri principle. Liszt assembles multiple operatic numbers into large-scale concert works, subjecting them to dramatic transformation, contrapuntal treatment, and symphonic pacing. Familiar melodies become vehicles for structural unity and expressive depth, transcending the genre’s earlier entertainment-driven aims.

Henry Grevedon: Sigismond Thalberg, 1836 (Gallica, btv1b8425259g)

Sigismond Thalberg’s Grande Fantaisie sur Moïse de Rossini, Op.33, offers a more restrained but highly influential model. While the work features a potpourri-like collection of operatic themes, Thalberg unifies them through lyrical flow and his famous “three-hand effect,” showcasing the refined elegance of mid-century salon culture.

In the violin repertoire, Henryk Wieniawski’s Fantaisie brillante sur des thèmes de Faust shows how potpourri principles extended beyond the piano. Drawing from Gounod’s opera, Wieniawski links well-known melodies within a structure that remains essentially potpourri-based, yet transforms each theme into a display for virtuosity and expressive flair.

By the twentieth century, the potpourri had largely fallen out of favour and was often associated with nostalgia or light entertainment. Nevertheless, some composers continued to engage with its collage-like principles in more reflective and stylistically complex ways. Ernst Krenek’s Potpourri, Op. 54 for Symphony Orchestra (1927) reimagines the genre within a modernist framework, employing fragmentation, sharp contrasts, and stylistic juxtaposition to evoke musical memory and historical continuity rather than simple melodic recognition.

R. Strauss: Die schweigsame Frau – Potpourri, Op.80 (1935)

A similarly late but highly sophisticated rethinking of the genre appears in Richard Strauss’s Die schweigsame Frau – Potpourri, Op. 80 (1935). Drawn from his comic opera Die schweigsame Frau, with a libretto by Stefan Zweig based on Ben Jonson’s Epicoene, the work assembles the opera’s principal themes into a continuous orchestral concert piece. Unlike nineteenth-century potpourris that prioritise immediate familiarity and lightness, Strauss’s treatment is symphonic in scope, with dense orchestration, harmonic complexity, and fluid transitions characteristic of his mature style. While the piece still functions as a concert synopsis of the opera, it simultaneously showcases Strauss’s mastery of orchestral colour, rhythmic vitality, and ironic wit.

Although often marginalised in narratives of “serious” music, the potpourri played a central role in nineteenth-century musical life. It shaped how audiences encountered opera outside the theatre, fueled the rise of instrumental virtuosity, and connected public concert culture with salon and domestic music-making. From Spohr, Hummel, and Giuliani to Sullivan, Strauss, Liszt, Thalberg, and Wieniawski, and finally to Krenek and Richard Strauss, the potpourri emerges not as a peripheral curiosity but as a flexible and enduring practice, one that continually adapted to changing tastes, performance contexts, and aesthetic priorities.

No comments:

Post a Comment