by

Some of the most powerful works of classical music ever are connected to the deaths of loved ones: spouses, siblings, friends, and others.

From Johann Sebastian Bach’s Chaconne, composed after the sudden death of his wife, to John Corigliano’s Symphony No. 1, a searing response to the AIDS crisis, all of these works demonstrate how grief has inspired composers over generations.

Today we’re looking at just a few of these unforgettable classical compositions.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Chaconne (c. 1720)

For his wife, Maria Barbara Bach

Given the limited amount of documentation that survives about his life, there is a lot we don’t know about Johann Sebastian Bach.

However, we do know that Bach’s monumental Chaconne – the final movement to his Partita No. 2 for solo violin – was written around the time of the death of his first wife, Maria Barbara Bach.

A silhouette of Maria Barbara Bach

Her death occurred in the summer of 1720 while Bach was traveling to Carlsbad with his employer, Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen. After two months away, he returned home to find her dead and buried.

The theory has been floated that the Chaconne was Bach’s response to her death: a heartbreaking outcry for solo violin that is technically demanding and lasts for a full quarter of an hour.

We’ll never know for sure, but it’s tempting to believe that this was his musical response to his grief.

Felix Mendelssohn: String Quartet No. 6 (1847)

For his sister, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel

Felix Mendelssohn and his older sister Fanny were artistic soulmates. Both were astonishing child prodigies who aided in each other’s musical development. But because of their gender, Felix was encouraged to pursue a career as a composer, while Fanny was prevented from doing so.

Felix Mendelssohn

Fanny’s sudden death in 1847 from a stroke devastated Felix. In response, he composed this fierce, raw quartet in the throes of grief, clearly trying to find a way to make sense of a world without her. The music veers manically from fury to heartbroken lamentation.

This is Felix’s last major work. He died just a few months later…also from a stroke.

Fanny Mendelssohn

Johannes Brahms: A German Requiem (1865-68)

For his mother

Johannes Brahms was famously tight-lipped about what specific events inspired his music. However, it is widely accepted that at least portions of his German Requiem were a response to the death of his mother in 1865, as well as the death of his mentor Robert Schumann in 1856.

When writing his Requiem, Brahms chose not to use the text of the traditional Latin Requiem Mass. Instead, he compiled passages from the German Bible, focusing on passages that provide comfort to the living.

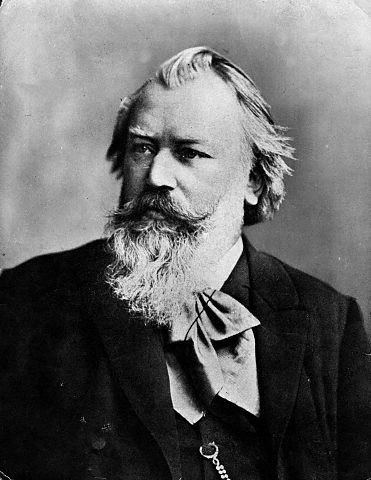

Johannes Brahms

As a result, this Requiem is less about the wrath (or beauty) of the afterlife, and more about addressing the emotional needs of the mourners left behind.

Modest Mussorgsky: Pictures at an Exhibition (1874)

For his friend Viktor Hartmann

Composer Modest Mussorgsky met artist Viktor Hartmann in 1868. Both men were passionate about the idea of creating overtly Russian art, and they became good friends.

Tragically, Hartmann died in 1873 of an aneurysm. After his death, Mussorgsky visited a massive tribute exhibition of Hartmann’s artwork. The experience inspired him to recreate Hartmann’s art in a piece of music.

Modest Mussorgsky

The piano suite that resulted, Pictures at an Exhibition, took just three weeks to write.

Every movement in Mussorgsky’s piano suite portrays a different piece of art. In between, variations on a “Promenade” theme appear again and again, symbolising Mussorgsky walking from one image to the next, contemplating the work of his dead friend in a new way each time.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Piano Trio (1881-82)

For his friend and colleague Nikolai Rubinstein

Tchaikovsky initially resisted composing a piano trio, doubting his ability to write for this particular instrumentation.

Despite those doubts, he began writing one in December 1881, nine months after the death of his friend and colleague, pianist Nikolai Rubinstein.

Nikolai Dmitrievich Kuznetsov: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1893

The first movement begins with one of Tchaikovsky’s most melancholy melodies.

The second movement is a set of variations, each passing by like pages of a photo album. In the end, the last variation fades into a heartbreaking version of the opening theme, now cast as a funeral march.

Tchaikovsky inscribed the score with “À la mémoire d’un grand artiste” (“To the memory of a great artist”).

It was premiered at a private performance on 23 March 1882, the first anniversary of Rubinstein’s death.

Franz Liszt: La Lugubre Gondola I (1882-85)

For his son-in-law Richard Wagner

Franz Liszt had a complex relationship with Richard Wagner, who married his daughter Cosima in 1870. (Both Richard and Cosima had been married to other people when they began their relationship.)

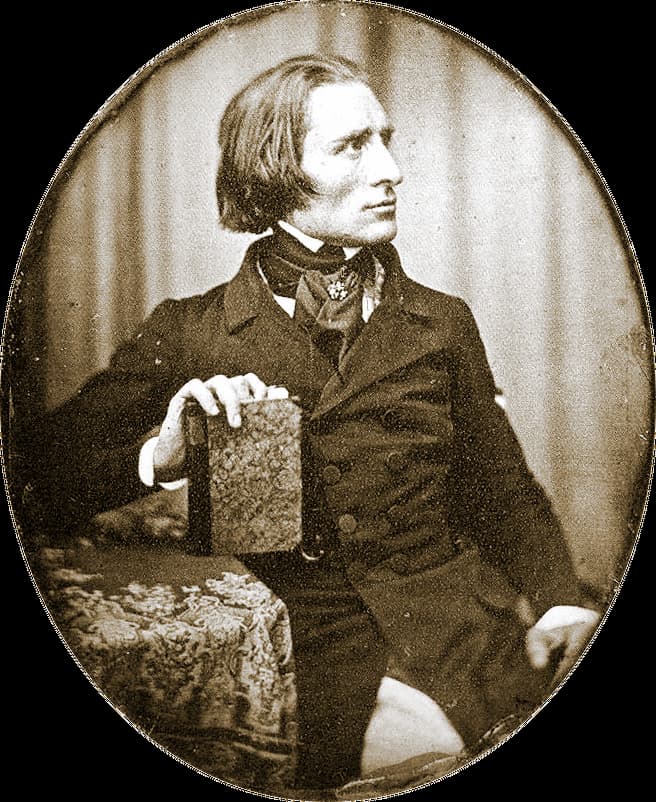

Hermann Biow: Franz Liszt, 1943

Despite occasional personal friction between them, Liszt’s respect for Wagner’s music predated the marriage by many years.

In late 1882, Liszt came to visit Wagner and his daughter at their home in Venice. The first version of his piece “La lugubre gondola” (“The Gloomy Gondola”) was written that December. It’s a grim work that seems to portend catastrophe.

Catastrophe struck a couple of months later, when Richard died suddenly. His death sent shockwaves across the European music world.

Richard Wagner

After Richard’s death, Liszt returned to “La lugubre gondola” and rewrote it. This version is known as “La lugubre gondola I.”

The music is strange, dark and stark, and filled with an uneasy, uncomfortable sense of dread.

Maurice Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-17)

For six friends who died in World War I

Each movement of Le Tombeau de Couperin is dedicated to a different friend lost in the war, but you’d never guess it: this is light, airy, seemingly carefree music.

Ravel believed that paying tribute to the fallen with joyful music was the best way to honour them.

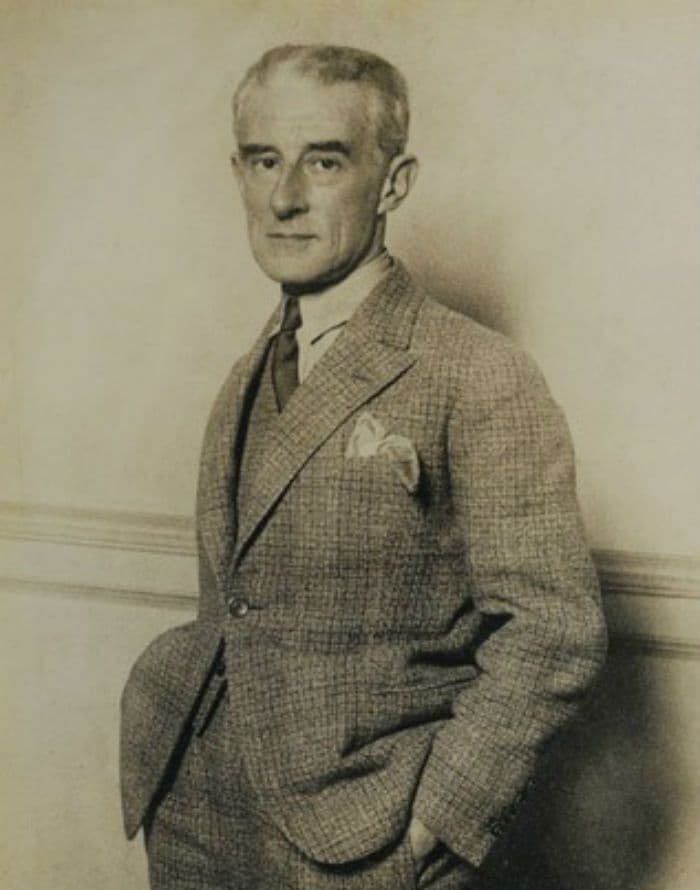

Maurice Ravel

The suite was premiered by pianist Marguerite Long, the widow of the man portrayed in the work’s Toccata movement.

By writing in a style reminiscent of French Baroque composer François Couperin, Ravel promoted French cultural identity during wartime…while also creating an emotional outlet for pianists and audiences struggling during the epidemic of wartime grief.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Piano Trio No. 2 (1943-44)

For his friend Ivan Sollertinsky

Critic, musicologist, and all-around polymath Ivan Sollertinsky was a dear friend of composer Dmitri Shostakovich. Reportedly, he spoke around thirty languages.

In February 1944, Sollertinsky died in his sleep at the age of 41. Officially, the cause was heart trouble, but dark rumours have circulated suggesting that he was murdered by the Soviet secret police.

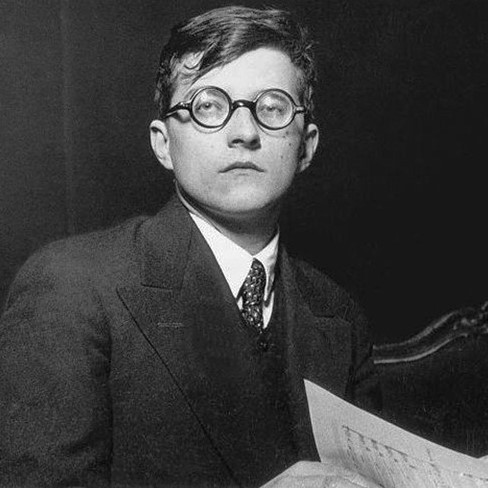

Dmitri Shostakovich

Shostakovich wrote to his widow:

“I cannot express in words all the grief I felt when I received the news of the death of Ivan Ivanovich. Ivan Ivanovich was my closest and dearest friend. I owe all my education to him. It will be unbelievably hard for me to live without him.”

Shostakovich had begun working on his second piano trio in December 1944. He turned the second movement into a dance both exuberant and macabre (Sollertinsky’s sister thought it was a musical portrait of her late brother). That was followed by a Largo: a heartbreaking goodbye to a beloved friend.

John Corigliano: Symphony No. 1 (1988-89)

For his friends who died of AIDS

John Corigliano’s searing first symphony is a monument to the lives lost during the AIDS crisis.

In the program notes for the premiere, he wrote:

“During the past decade, I have lost many friends and colleagues to the AIDS epidemic, and the cumulative effect of those losses has, naturally, deeply affected me. My First Symphony was generated by feelings of loss, anger, and frustration. A few years ago, I was extremely moved when I first saw ‘The Quilt,’ an ambitious interweaving of several thousand fabric panels, each memorialising a person who had died of AIDS, and, most importantly, each designed and constructed by his or her loved ones. This made me want to memorialise in music those I have lost, and reflect on those I am losing.”

John Corigliano

The first movement (called “Apologue: Of Rage and Remembrance”) is dedicated to a pianist friend, the second to a music executive, and the third to a cellist.

Anna Clyne: Within Her Arms (2008-09)

For her mother

In 2008, composer Anna Clyne’s mother died. That same year, she began a fifteen-part string work she’d call Within Her Arms.

The work received rave reviews from critics across America. The New Yorker’s Alex Ross described it as “a fragile elegy for fifteen strings; intertwining voices of lament bring to mind English Renaissance masterpieces of Thomas Tallis and John Dowland, although the music occasionally breaks down into spells of static grief, with violins issuing broken cries over shuddering double-bass drones.”

Anna Clyne

In the work’s official program notes, Clyne chose not to write any explanation herself, but rather to quote a poem by the poet Thich Nhat Hanh. That fragment includes the lines:

Earth will keep you tight within her arms dear one—

So that tomorrow you will be transformed into flowers-

This flower smiling quietly in this morning field—

This morning you will weep no more dear one—

For we have gone through too deep a night…