by Interlude Contributors January 6th, 2026

From the personal struggles of legendary figures to the electrifying rise of new stars, these are the stories that resonated most deeply with you. We invite you to dive back into these favorites or discover for the first time what made them the most loved reads of 2025.

Are you ready? Here is the countdown of our most popular articles from the past year.

10. Mitsuko Uchida (Born on December 20, 1948)

The Art of Listening

Full article: https://interlude.hk/mitsuko-uchida-born-on-december-20-1948-the-art-of-listening/

Mitsuko Uchida © Geoffroy Schied

Kicking off our list is a profound look into the mind of a piano legend. This article celebrated Mitsuko Uchida‘s unique artistic philosophy. It’s the act of listening that defines her interpretations and makes her performances of Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven so deeply resonant:

“In a sense, Mitsuko Uchida embodies an alternative model of musical greatness. Not the conqueror of the keyboard, not the charismatic hero, but the attentive listener. Her artistry suggests that music-making, at its highest level, is an ethical practice.”

9. The Tastes and Smells of the Holiday Season

Full article: https://interlude.hk/the-tastes-and-smells-of-the-holiday-season/

The Spanish Dance – Chocolate, 2013 (New York City Ballet)

From the crisp, bright fanfares that evoke the scent of pine to the warm, rich orchestrations that feel like a sip of hot chocolate, this delightful holiday feature paired the festive tastes and aromas of the season with their perfect musical counterparts. It’s a wonderfully imaginative article that enhances the appreciation of both food and music, making the holiday season feel richer and more vibrant.

8. 15 Pieces of Classical Music about Animals

Full article: https://interlude.hk/15-pieces-of-classical-music-about-animals/

Image created by FLUX-dev

From the grand to the whimsical, the animal kingdom has always been a rich source of inspiration for composers. This article went far beyond Saint-Saëns’s famous Carnival of the Animals to uncover a whole menagerie of musical creatures:

“Composers have written about their own pets, such as Chopin, who wrote a waltz inspired by his dog chasing its tail, or Scarlatti, whose cat walking over the keyboard gave him a theme for a fugue. Other composers have been inspired by the sounds of nature, from the songs of birds to the buzzing of insects. Let’s look at some of the best classical music about animals.”

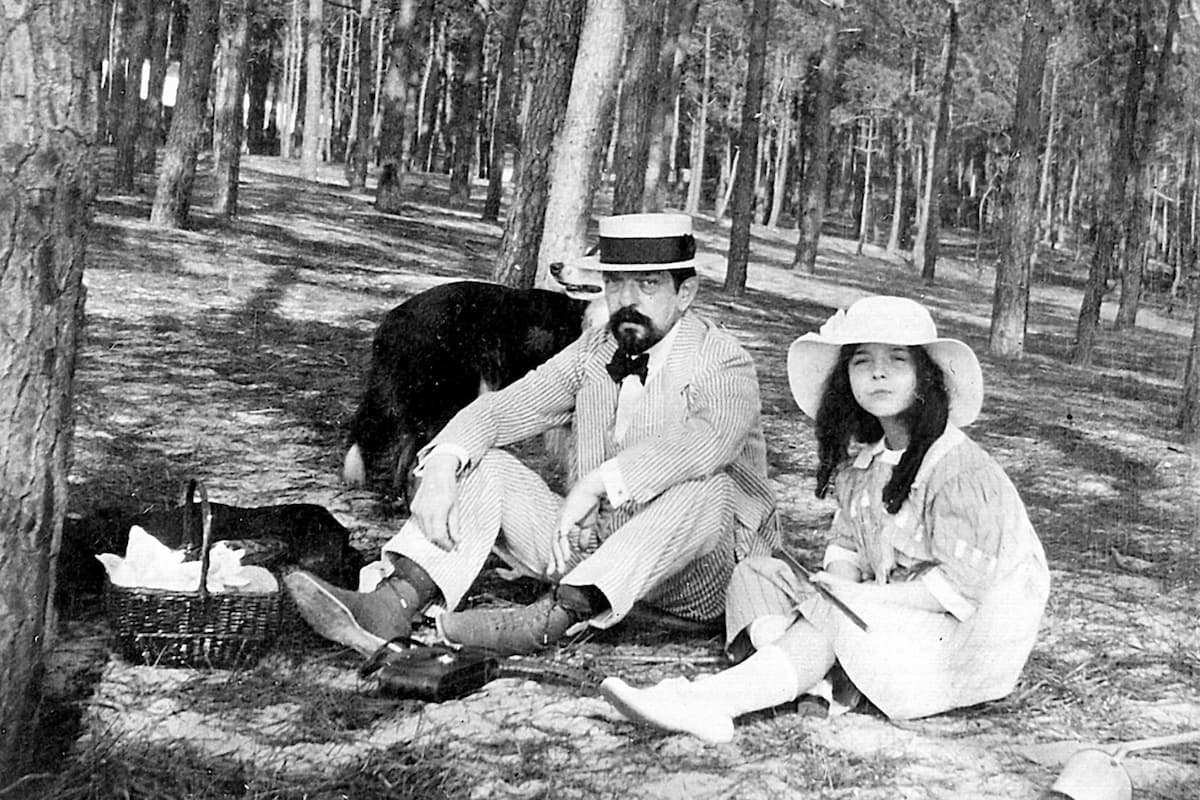

7. Dmitri Shostakovich’s Three Fascinating Wives

Full article: https://interlude.hk/dmitri-shostakovichs-three-fascinating-wives/

Shostakovich and his wife Nina

The life of Dmitri Shostakovich was a tightrope walk between artistic genius and political terror. This gripping article illuminated his world through the eyes of the three women he married: Nina Varzar, Margarita Kainova, and Irina Antonovna Spunskaya. The stories of these relationships provide valuable insight into Shostakovich’s psychology, work, and music.

6. Get to Know Yunchan Lim With These Ten Video Clips

Full article: https://interlude.hk/get-to-know-yunchan-lim-with-these-ten-video-clips/

Yunchan Lim

The classical world was set ablaze by the arrival of Yunchan Lim, the young pianist who stunned the world with his historic win at the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. This article curated the essential video moments that capture his phenomenal talent and endearing personality:

“Together, these clips sketch a portrait of Yunchan Lim as not just another competition winner, but as someone who has the capacity to be one of the greatest pianists of his generation.”

If you’re just discovering him, these videos are the perfect introduction to why the world is paying attention!”

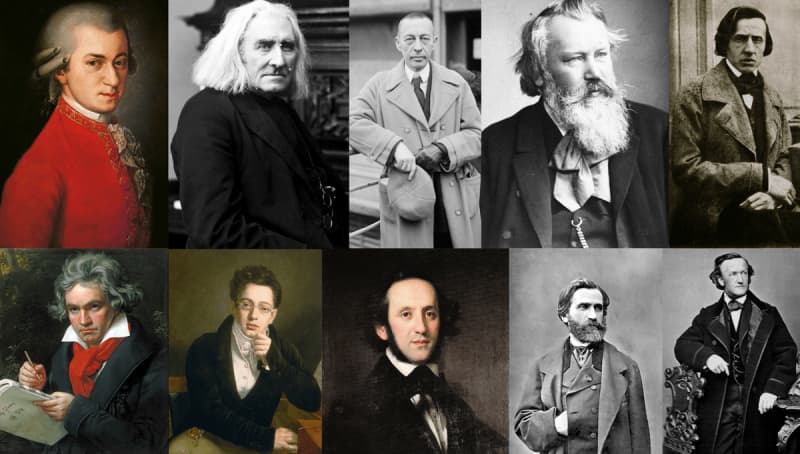

5. Mozart’s Piano Masterpieces: 10 Most Popular Piano Sonatas

Full article: https://interlude.hk/mozarts-piano-masterpieces-10-most-popular-piano-sonatas/

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Here’s a guide to Mozart’s most beloved piano sonatas, an essential resource for pianists, students, or simply admirers of Mozart’s genius.

“The piano sonatas of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are some of the most recognizable and well-known pieces of classical music… Mozart composed his piano sonatas between 1775 and 1789, during the height of his creative powers. While he only wrote 18 of them, they are all masterpieces in their own right. Here are 10 of his most popular piano sonatas, which are a great introduction to his solo piano music.”

4. Three Pianists Who Survived the Nazi Concentration Camps

Full article: https://interlude.hk/three-pianists-who-survived-the-nazi-concentration-camps/

Lena Stein-Schneider, Alice Herz-Sommer and Marian Filar

This article paid tribute to Alice Herz-Sommer, Lena Stein-Schneider, and Marian Filar, who endured the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust, using music as a shield, a solace, and a reason to live.

“Even without a piano I always had music in my heart, which is why I never thought of suicide, no matter how bad things got. Plus, I wouldn’t have wanted to give those SS bastards the satisfaction of thinking they had triumphed over me.”

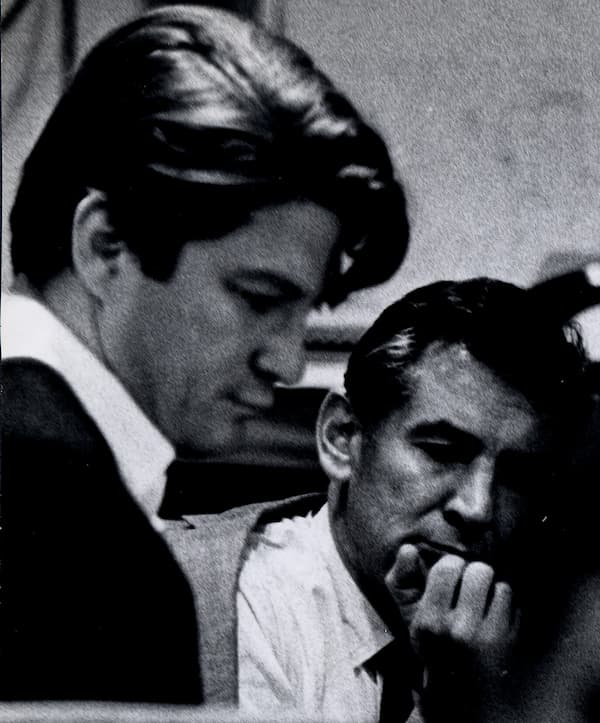

3. Seven of Leonard Bernstein’s Lovers

Full article: https://interlude.hk/seven-of-leonard-bernsteins-lovers/

David Oppenheim and Leonard Bernstein

While Bernstein was publicly a family man, married to Felicia Montealegre, he also navigated a life of secret relationships with men. This article respectfully examines seven of these significant relationships, shedding light on the personal conflicts and emotional turmoil Bernstein faced in an era when such a life had to be hidden.

2. Untangling Hearts: Klaus Mäkelä and Yuja Wang

Full article: https://interlude.hk/untangling-hearts-klaus-makela-and-yuja-wang/

Yuja Wang and Klaus Mäkelä

When two of classical music’s most dynamic young superstars form a personal and professional partnership, the world pays attention. This article tapped directly into the zeitgeist, exploring the electrifying collaboration between conductor Klaus Mäkelä and pianist Yuja Wang.

1. Yuja Wang: Electrifying Artistry

Full article: https://interlude.hk/yuja-wang-electrifying-artistry/

Yuja Wang

And at number one, it’s no surprise that our most-read article of 2025 is a deep dive into the artist who has captured the imagination of the entire world: Yuja Wang. This definitive profile celebrated everything that makes her a true phenomenon—her staggering virtuosity, her fearless stage presence, and her revolutionary spirit. Sample some of her most iconic recordings here again!

And there you have it—the ten articles that sparked the most conversation and captured your attention in 2025. We wish you a wonderful 2026, filled with breathtaking performances and beautiful discoveries.

What stories do you want to read this year? Are there composers, musicians, or musical topics you’re eager for us to explore? Let us know in the comments below.