But it’s a bit rarer when world-renowned instrumentalists turn to conducting after a brilliant career as a soloist. Some extremely talented musicians do (or did) both such as Daniel Barenboim, Leonard Bernstein, Pinchas Zukerman, and Mitsuko Uchida.

Cellists becoming conductors seem to lead the pack. Did you know these 15 conductors were cellists in a previous life?

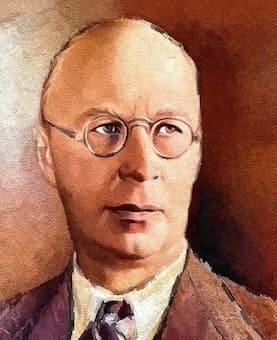

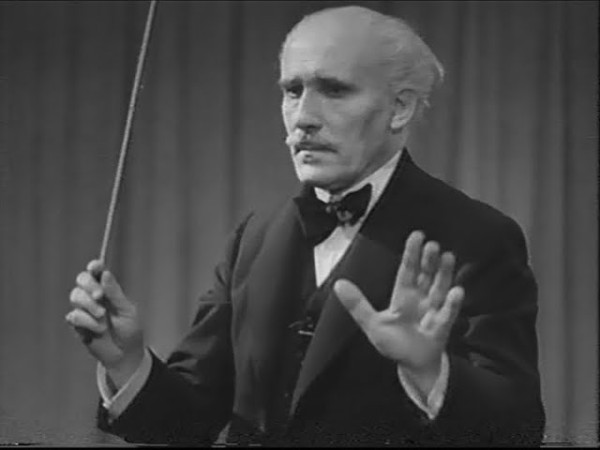

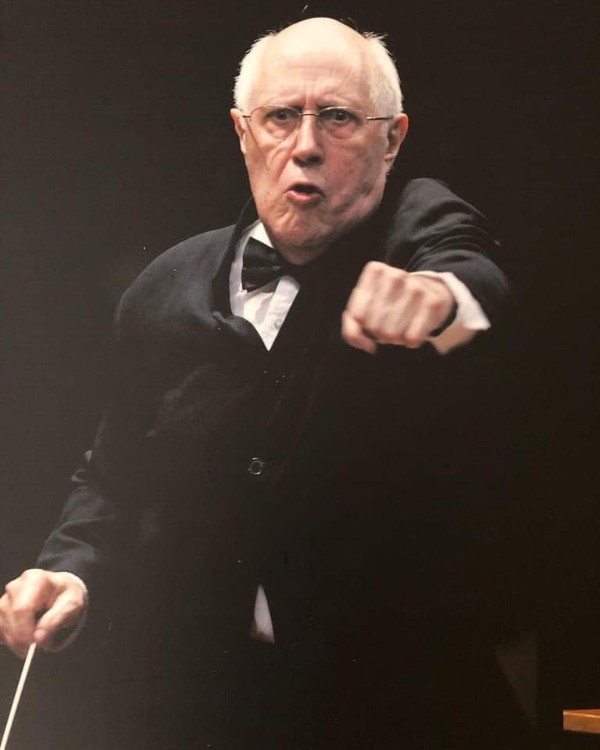

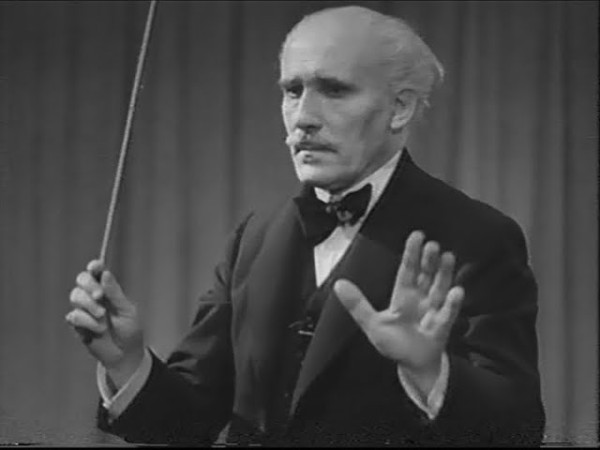

Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) is considered by many to be the greatest conductor of all time. A perfectionist, with a phenomenal ear, an outstanding memory, and relentless intensity, his outbursts are legendary. He began as a cellist and even played the premiere of Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello in 1887 at La Scala while Verdi supervised. Later, Toscanini became principal conductor at La Scala in Milan, the Metropolitan Opera (1908-1915) and the New York Philharmonic (1926-1936), as well as the famous NBC Symphony Orchestra from 1937-1954, becoming a household name. He got results. Listen to him berate the orchestra, especially the bass section (scary!), and then to this sparkling interpretation of Mozart’s Cassation in G major, the “Toy” Symphony with the NBC Symphony Orchestra.

Toscanini screaming!

Sir John Barbirolli

Sir John Barbirolli (1899-1970) a British cellist who became a conductor, was famous for his vibrant and expressive music making as well as his sarcastic and acerbic wit. He began his music lessons on the violin, but continually wandered around when he was practising, constantly underfoot. Barbirolli’s grandfather bought him a small cello. He couldn’t walk around playing that! Barbirolli played in theatres and cafés before joining Queen’s Hall Orchestra in 1916, becoming their youngest orchestral musician, and after World War I, he played in the London Symphony. Barbirolli succeeded Toscanini in 1936 as the music director of the New York Philharmonic (1936-1941). In 1943, Barbirolli returned to Manchester (miraculously missing being a passenger on the aircraft that was shot down with Leslie Howard on it) and rebuilt the Hallé, decimated by WWII. Later, he conducted the Houston Symphony (1960-1967), and he was a frequent guest conductor with the most important orchestras.

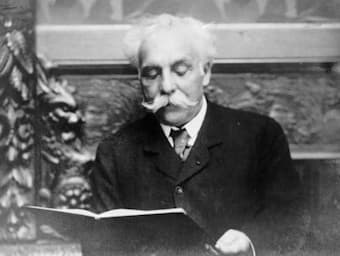

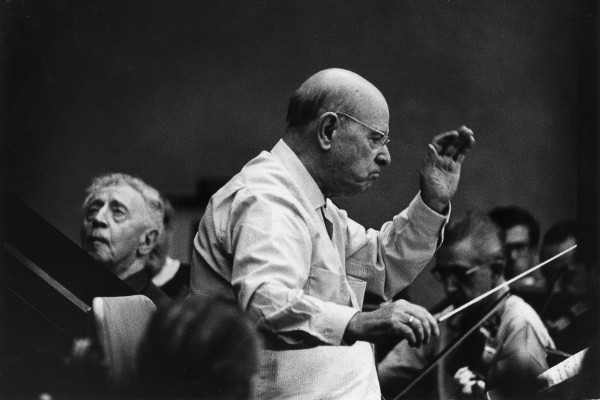

Pau (Pablo) Casals

Pau (Pablo) Casals (1876-1973), one of the world’s most prominent cellists, a composer, conductor, and humanitarian, toured the world playing in the most wonderful concert halls in the world. In 1919, he founded the Pau Casals Orchestra in Barcelona, which he conducted until 1936. Casals made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in 1904 and his Carnegie debut as a conductor in 1922. In 1927, the centenary of Beethoven’s death, Casals was invited to play and conduct the Vienna Philharmonic. He appeared frequently in Germany, but despite invitations from Wilhelm Furtwängler in 1934 to perform with the Berlin Philharmonic, Casals refused to play in Germany again with the rise of the Nazi regime. A lifelong and staunch defender of freedom, in 1939, due to Franco’s victory in the Spanish Civil War, Casals fled to Prades, France, an isolated Catalan village, to protest the Spanish fascist regime. Illustrious musicians repeatedly appealed to him to change his decision to live in exile, but Casals indicated that silencing the music, “is not a matter of money; it is just a matter of morality.” A group of musicians decided they must go to him instead and founded the now famous Prades Festival in 1950. Casals moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico, in 1957 and lived there until his death. Widely credited with discovering and promoting the Bach Six Solo Cello Suites in 1890 in Barcelona, his words still inspire generations of musicians:

“Music is never the same for me, never. Every day, there is something new, fantastic, and extraordinary. Bach, like nature, is a miracle!”

Read more from ‘Pablo Casals: a total musician’.

Heinrich Schiff © Dan Porges/Getty Images

Heinrich Schiff (1951-2016), an Austrian cellist, studied with André Navarra, making his London and Vienna debuts in 1971. He is esteemed for his performances and recordings of the Bach Solo Cello Suites, Shostakovich Concertos, and the Brahms Double Concerto, featuring Frank Peter Zimmerman. Schiff was also a champion of new music. He made his conducting debut in 1986 and subsequently was appointed to the Northern Sinfonia from 1990 to 1996, the Vienna Chamber Orchestra from 2005 to 2008, and was also associated with the Copenhagen Philharmonic. Sadly, he suffered a stroke in 2008, which compelled him to relinquish playing the cello and to focus on conducting. Schiff’s notable students include Truls Mørk, Gautier Capuçon and Natalie Clein. Listen to him play the fiery second movement of Shostakovich’s Sonata Op 40.

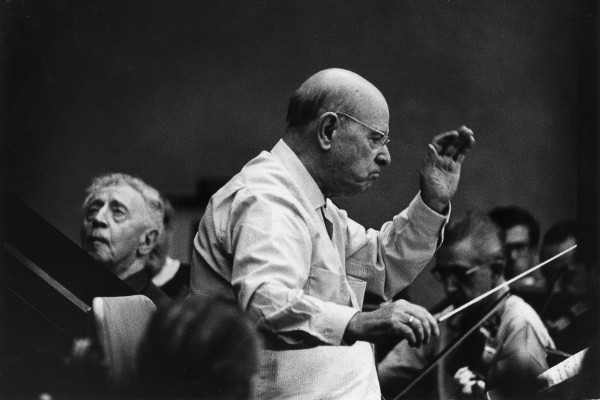

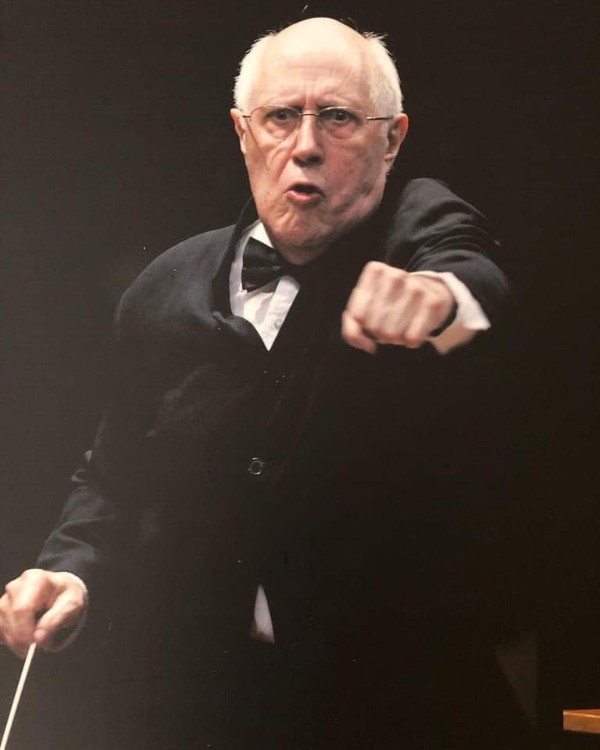

Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929-2016) was a conductor, music researcher, and pioneer of historical performance practice. Harnoncourt, a cellist in the Vienna Symphony for 17 years before he became a conductor, performed with and learning from such illustrious maestros as Herbert von Karajan, Karl Richter, Karl Böhm, and Wilhelm Furtwängler. His debut as a conductor occurred in 1972 at La Scala, featuring Il ritorno d’Ulisse in Patria by Monteverdi. He held the position of professor of historical performance practice at the Mozarteum Salzburg from 1973 to 1992. In the 1990s and 2000s, he shifted to romantic music and the music of the 20th century. Here he is conducting the Kyrie from Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis.

Mstislav Rostropovich in tutu

Mstislav Rostropovich (1927-2007) one of the great cellists of our time who inspired numerous composers to write for him, (nearly 200 works and many commissioned by him), possessed a commanding and dazzling technique. He championed Soviet composers, as well as the cello as a solo instrument, and he was a fine pianist. His energy seemed inexhaustible. Sometimes he said only partially in jest, “when I am tired of playing the cello, I accompany my wife on the piano, and when I tire of that, I teach.” Did I mention he regularly slept only 3 hours a night? He was outspoken in his humanitarian ideals, so much so that the Soviet regime began to penalise him for his outspoken support of fellow artists such as the writer Solzhenitsyn. Slava arrived in exile in London in 1974. Rostropovich had had the conducting bug at age 13, but his father wisely cautioned him to wait. In the west, he rebuilt his career, becoming music director and conductor of Washington’s National Symphony Orchestra in 1977, a position he held until 1994. I can attest to his magnetic and effusive personality, radiating especially when he led master classes or when he conducted or performed for humanitarian causes. Perhaps you didn’t know he was a jokester?

Mstislav Rostropovich in tutu

Victor Herbert

Victor Herbert (1859-1924), best known for his composing, operettas, stage music, and musicals (Babes in Toyland), began his career as a cellist in Vienna and Stuttgart. Once he moved to the US, he was the assistant conductor with the New York Philharmonic for 11 seasons, conducted the Pittsburgh Symphony (1898-1904) and then his own Victor Herbert Orchestra. He continued to perform as a cello soloist throughout the country. His numerous cello compositions include the lovely Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor Op 30.

Alfred Wallenstein

Alfred Wallenstein (1898-1983) was an American cellist and conductor. His musical family emigrated from Europe to Los Angeles in 1905, and when Alfred turned 8, his father gave him a choice between a bicycle or a cello. Fortunately for the music world, he chose the latter. Emerging as a child prodigy, he soon joined the San Francisco Symphony and then the Los Angeles Philharmonic, their youngest member. After studying with Julius Klengel in Leipzig, he was snapped up to play with the Chicago Symphony, performing for seven seasons there. Always looking to enrich himself, he auditioned for Toscanini, and in 1929, Wallenstein became the New York Philharmonic principal cello, often appearing as a soloist. In 1931, Wallenstein began to conduct, becoming the Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, conducting major orchestras as a guest, leading music festivals, and in 1968, joining the faculty of the Juilliard School of Music.

Ennio Bolognini © alchetron.com

Ennio Bolognini (1893-1979) a cellist, guitarist, composer, conductor, a professional boxer and pilot, hails from Argentina. He was the principal cello of the Chicago Symphony for one season. Bolognini conducted at Grant Park and later founded the Las Vegas Philharmonic Orchestra (not to be confused with the orchestra today). Here’s an anecdote: One day, when Casals, Piatigorsky and Feuermann were together, Feuermann said, “Pablo. It is not you, nor Grisha, nor I who is the greatest cellist in the world. It is Ennio Bolognini.” He was quite a character. Ennio, as a young teenager, played the Swan with Saint-Saëns and the Sonata of Richard Strauss with the composer. Here is a lovely example of one of his cello bonbons played by cellist Christina Walevska.

Read more from ‘Legendary Cellists Christina Walevska and Ennio Bolognini’.

Frieda Belinfante

Frieda Belinfante (1904-1995), the Dutch cellist, conductor, and Nazi-resistance fighter, was invited by the Concertgebouw management in Amsterdam in 1937 to form and direct a chamber orchestra, a position she held until 1941—the first woman to conduct a professional ensemble in Europe. Belinfante also appeared with the Dutch National Radio and other orchestras of Europe as a guest conductor. After the war, she joined the music faculty of UCLA in 1949 to teach cello and conducting, and she became the music director of the Orange County Philharmonic Society.

Read more from ‘Forgotten Cellist, Conductor, Heroine and LGBTQ advocate: Frieda Belinfante’.

Susanna Mälkki

Susanna Mälkki (1969-) is a Finnish conductor who won first prize at the Turku National Cello Competition. From 1995 to 1998, she was principal cello of the Gothenburg Symphony. Currently the Chief Conductor emeritus of the Helsinki Philharmonic, she was their Chief Conductor from 2016 to 2023, and Principal Guest Conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic from 2017 to 2022. Mälkki has been in demand as a guest conductor worldwide in opera houses and with orchestras including the Wiener Symphoniker, Berlin Philharmoniker, Cleveland Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, and the Chicago, Boston, and London Symphonies. Meet Susanna Mälkki in this short video.

Conductor Susanna Mälkki on Her Met Opera Debut

Han-Na Chang © Luciano Romano

Han-Na Chang (1982-), a South Korean conductor and cellist, began playing the piano at age 3 and the cello at the age of 6. She studied with Mstislav Rostropovich, winning the First Prize at the Fifth International Rostropovich Cello Competition in Paris in 1994 at the age of 11. Her recording of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations and Saint-Saëns Concerto is with her mentor conducting. She is now the chief conductor of the Trondheim Philharmonic. Chang is travelling widely, appearing with orchestras the world over. She recently made her debut with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducting Beethoven’s Symphony No. 4 and Richard Strauss’s Don Quixote with Tatjana Vassiljeva-Monnier, first principal cello, as soloist, playing the role of the noble knight, and principal viola Santa Vižine playing the role of Sancho Panza—three women artists featured together!

Nicolas Altstaedt

Nicolas Altstaedt (1982-), the compelling French-German cellist, has performed widely as a soloist from Berlin to Seoul, and Detroit to London, and he has performed chamber music with illustrious collaborators. As a conductor, he has worked with the Scottish and Munich Chamber Orchestras and the Zurich Chamber Orchestra. In 2015, Adam Fisher chose him to succeed him as the artistic director of the Haydn Philharmonie through 2022. He has not been idle for a minute during the 2024/25 season, which included several recordings, impressive debuts as a cellist, and conducting debuts with the Budapest Festival Orchestra, Warsaw Philharmonic, and Kyoto Symphony. Hear him play a work of fellow conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen, 2 Fragments for Lockenhaus: Ritual and Pentatonic Chain.

Eric Jacobsen

Eric Jacobsen (1982-), an American conductor and cellist, is the artistic director and co-founder of the chamber orchestra The Knights and the music director of the Virginia Symphony. He is in his 10th season as Music Director of the Orlando Philharmonic. As a cellist, he and his brother founded the String quartet Brooklyn Rider, and he performed often with Yo-Yo Ma as a member of the Silk Road Ensemble.

Klaus Mäkelä © Marco Borggreve

Klaus Mäkelä (1996-) At age 31, Finnish conductor will be the second youngest chief conductor of the Concertgebouw ever when he takes on the role in 2027, and he has recently been appointed Music Director Designate of the Chicago Symphony, once again the youngest to lead the orchestra. He currently holds positions with the Oslo Philharmonic, with whom he has made several recordings, and four seasons with the Orchestre de Paris. As a cellist, he’s performed at the famed Verbier Festival (including this summer), and he is in demand as a guest conductor with orchestras including the London Symphony, the Cleveland Orchestra, and the Berliner Philharmoniker, among others. Hold on to your seats. Here he is conducting the Infernal Dance from Stravinsky’s Firebird.

And for a contrast a sublime ending to Mahler Symphony No. 8 with the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam this year.

Are you convinced? Cellists are a unique bunch who may have extraordinary communicative abilities in addition to their cello-playing gifts.

*inspired by a social media post of the Concertgebouw

Playing is the easy part. My stomach clenches when I think of the likely technological complications…no projector or screen, or they won’t know how to hook it up, or the PowerPoint won’t work, or the more common problems—no decent chair, inferior lighting, no place to warm up, the hall will be freezing, or we arrive on the wrong date, like the dream I had the previous night.

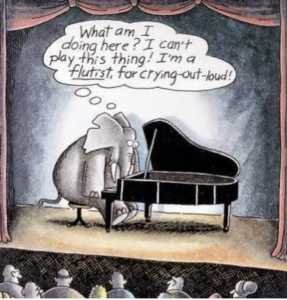

Playing is the easy part. My stomach clenches when I think of the likely technological complications…no projector or screen, or they won’t know how to hook it up, or the PowerPoint won’t work, or the more common problems—no decent chair, inferior lighting, no place to warm up, the hall will be freezing, or we arrive on the wrong date, like the dream I had the previous night. We heave the cover off and muscle the piano to the middle of the stage. As I start unpacking my cello I hear a little squeal of dismay. “The piano is locked!” Heather whispers. She asks the technology person if he has the key. “Just have to track down the building manager,” he says, “Hopefully she hasn’t left for the day.” Several minutes click by but he returns triumphant, with a key. After wiggling it this way and that, he realizes it’s not the right key, and scurries up the aisle, out of the hall, and down the long corridor. It is now 15 minutes prior to concert time. Not a young man, he returns gasping, forgoes the stairs, and leaps onto the stage clutching a key. He tries it. We hear several expletives because this one doesn’t work either. Heather and I exchange a glance verging on panic. The technology person rushes off again. Moments before the program is to begin, he appears wheezing alarmingly, with a third key. It magically releases the ivory keys with just enough time for Heather to play one quick scale before the performance. Who knew the piano would be wearing a chastity belt?

We heave the cover off and muscle the piano to the middle of the stage. As I start unpacking my cello I hear a little squeal of dismay. “The piano is locked!” Heather whispers. She asks the technology person if he has the key. “Just have to track down the building manager,” he says, “Hopefully she hasn’t left for the day.” Several minutes click by but he returns triumphant, with a key. After wiggling it this way and that, he realizes it’s not the right key, and scurries up the aisle, out of the hall, and down the long corridor. It is now 15 minutes prior to concert time. Not a young man, he returns gasping, forgoes the stairs, and leaps onto the stage clutching a key. He tries it. We hear several expletives because this one doesn’t work either. Heather and I exchange a glance verging on panic. The technology person rushes off again. Moments before the program is to begin, he appears wheezing alarmingly, with a third key. It magically releases the ivory keys with just enough time for Heather to play one quick scale before the performance. Who knew the piano would be wearing a chastity belt? Brazilian pianist, Eliane Rodrigues handled her piano malfunction nightmare with aplomb. She began her program of Chopin’s Preludes, Polonaises, and Piazzolla’s works, with Chopin’s Polonaise Fantasie Op.61 only to discover the sostenuto pedal had a mind of its own. Once she hit a note the tone kept ringing, and ringing—pedal without using a pedal. “Alo?” Rodrigues said attempting to get the stage manager’s attention. The dilemma was conveyed to the staff and one could hear a flurry of activity offstage as they hurried to find a substitute piano. Rodrigues continued to play a few non-programmed tunes while the stagehands rushed onstage. They unlocked the wheels of the piano to position it deeper into the stage. Rodrigues stood and remained standing and playing as they cordoned off the piano and the piano bench. The audience watched as the piano and Rodrigues lowered—down, down, disappearing into the bowels of the stage. She could be heard from the depths. Within a few moments the audience caught sight of the top of Rodrigues’ head, and the piano and the pianist ascended into view, Rodrigues still standing and playing a different piano.

Brazilian pianist, Eliane Rodrigues handled her piano malfunction nightmare with aplomb. She began her program of Chopin’s Preludes, Polonaises, and Piazzolla’s works, with Chopin’s Polonaise Fantasie Op.61 only to discover the sostenuto pedal had a mind of its own. Once she hit a note the tone kept ringing, and ringing—pedal without using a pedal. “Alo?” Rodrigues said attempting to get the stage manager’s attention. The dilemma was conveyed to the staff and one could hear a flurry of activity offstage as they hurried to find a substitute piano. Rodrigues continued to play a few non-programmed tunes while the stagehands rushed onstage. They unlocked the wheels of the piano to position it deeper into the stage. Rodrigues stood and remained standing and playing as they cordoned off the piano and the piano bench. The audience watched as the piano and Rodrigues lowered—down, down, disappearing into the bowels of the stage. She could be heard from the depths. Within a few moments the audience caught sight of the top of Rodrigues’ head, and the piano and the pianist ascended into view, Rodrigues still standing and playing a different piano.

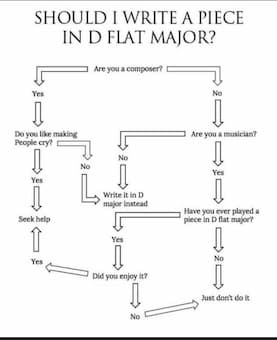

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”

“What? D-Flat Major?” Most string players wail, “that’s a key signature with FIVE FLATS!”