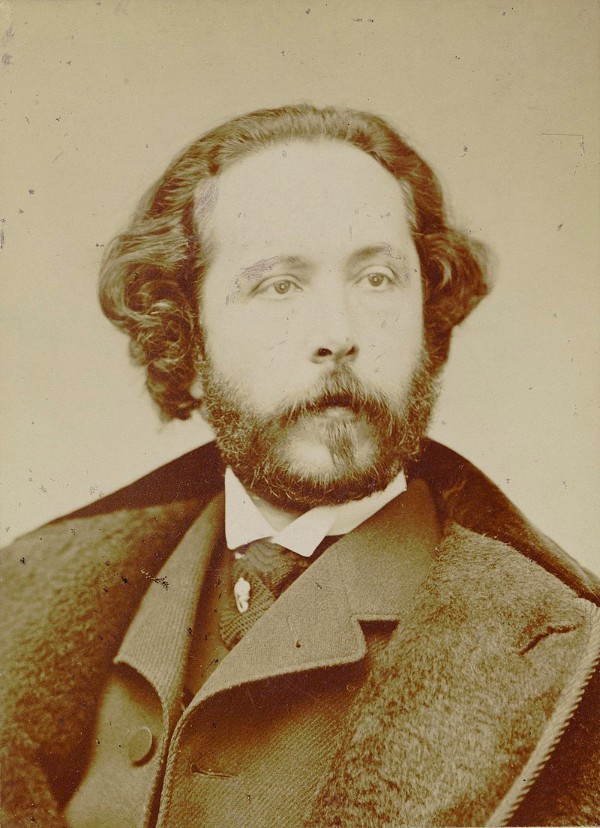

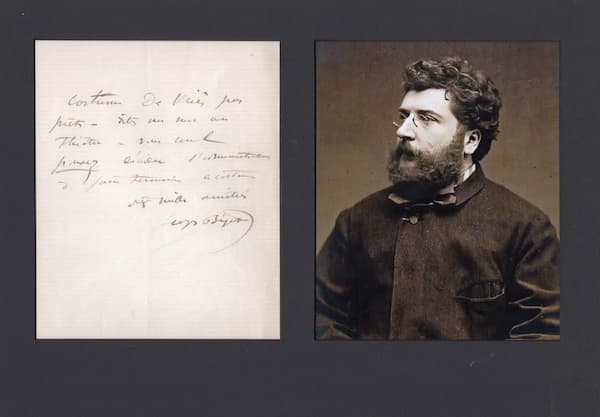

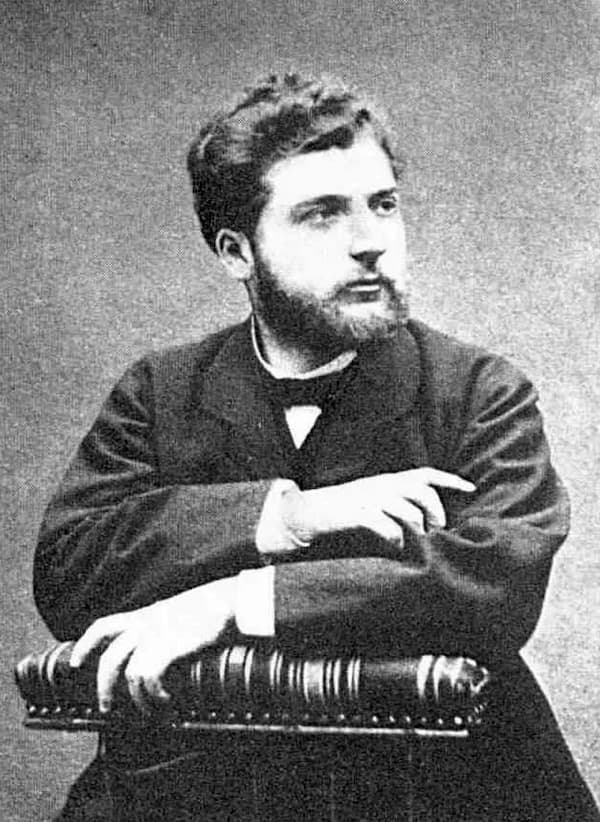

Young Georges Bizet, 1860

In 1861 Bizet met Franz Liszt and sight-read a fearsomely difficult work that Liszt had just performed. Liszt commented, “my young friend, I had thought that there were only two men capable of struggling victoriously against the difficulties with which I enjoyed peppering this piece; I was mistaken; there are three of us, and the youngest of us is perhaps the boldest and most brilliant.”

In terms of praise, it doesn’t get any better! However, Bizet performed very little in public as he was not interested in a career as a concert pianist. “I find the performer’s trade an odious one,” he wrote to a friend. He also feared that being labelled a virtuoso might overshadow his intended career as an operatic composer.

As we all know, Bizet would distinguish himself as a composer of orchestral and operatic music, but on the occasion of the anniversary of his death on 3 June 1875, let’s feature some of his beautiful piano miniatures.

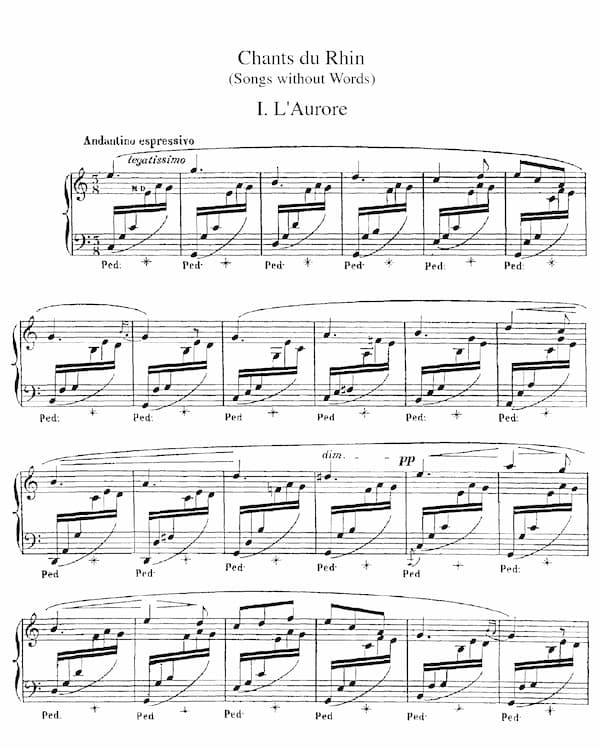

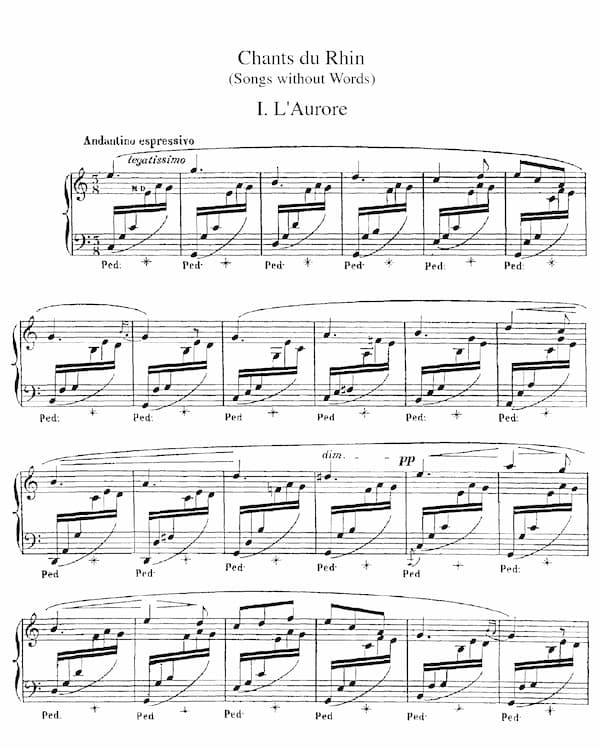

Chants du Rhin

Georges Bizet’s Chants du Rhin

In 1865, Georges Bizet composed his Chants du Rhin, paying homage to this legendary waterway that inspired lots of music. However, this collection of pieces with the subtitle “Songs without words,” was not inspired by an actual river journey but by six stanzas of poetry written by Joseph Méry.

Bizet composed a cycle of six dreamy miniatures on the subject of the river and its inhabitants, and he freely translated the poems into musical terms. “L’Aurore” features an expressive melody with arpeggio accompaniment, while “Le Départ” vividly portrays a river song of young woodcutters.

“Les Confidences” and “Le Retour” whisper confidences and salute the river, but all songs are symmetrically grouped around the central “La bohémienne.” The overall theme thus concerns a beautiful and free-spirited gypsy girl. And all that ten years before Carmen!

Trois esquisses musicales

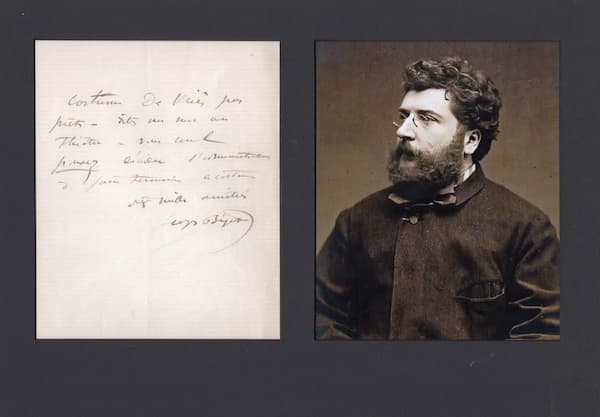

Georges Bizet’s autograph letter

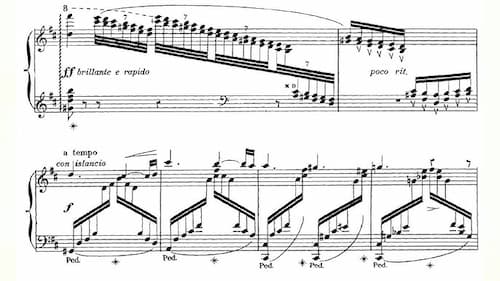

Bizet composed his Trois esquisses musicales in 1857, and this set of three piano sketches showcase his early brilliance as a pianist and composer. Written when he was in his early twenties, these “musical sketches” reflect his virtuosic piano writing and his knack for vivid and evocative storytelling.

The set opens with a spirited “Rondo turque,” a lively rondo that pulses with exotic, Turkish-inspired rhythms. It conjures images of bustling bazaars and whirling dancers, and virtuosic flourishes provide for an almost mischievous spirit.

The “Sérénade” shifts to a tender, flowing melody, like a moonlit song drifting over calm waters. Its lyrical warmth and delicate textures create a dreamy, intimate mood, inviting quiet reflection. Finally, the “Caprice” dances with impish delight, its sparkling runs and sudden dynamic shifts showcasing Bizet’s wit and pianistic flair.

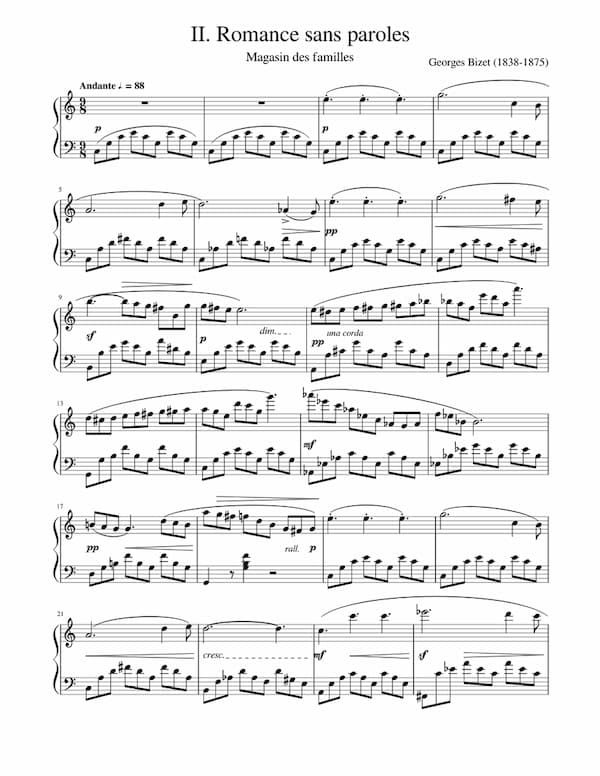

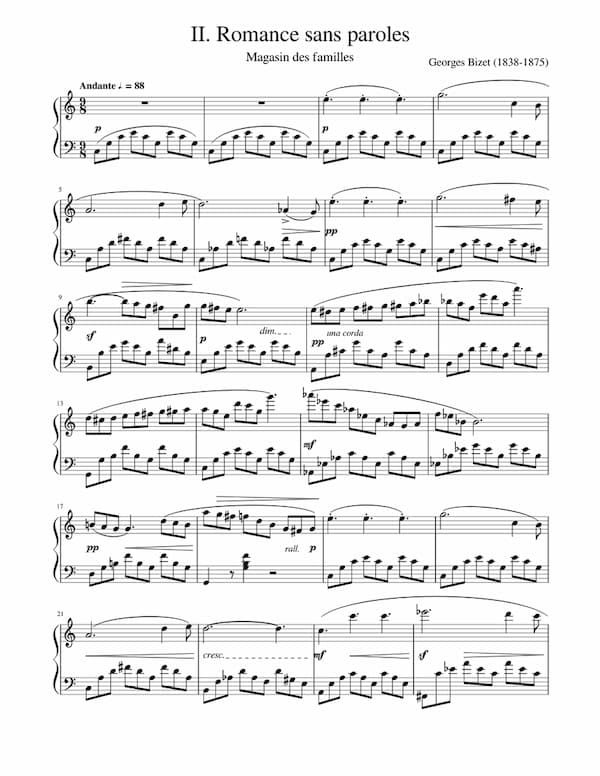

Magasin des familles

Georges Bizet’s Magasin des familles – II. Romance sans paroles

The three pieces published as musical supplements in the Magasin des familles (Family Magazine) were composed during Bizet’s Prix de Rome period. They reflect his early musical style, blending lyrical Romanticism, exotic influences and a vigorous dance-like energy.

“Méditation religieuse” opens the set in a serene and contemplative mood. It features a gentle hymn-like melody in the minor key that evokes a quiet moment of spiritual reflection. The piece has an almost prayerful quality, perfectly suited for the introspective tastes of the Magasin des Familles readers.

The “Romance sans paroles” is a lyrical gem that gently flows with tender and wordless emotion, while “Casilda” sounds a polka-mazurka full of vibrant dance energy. The syncopated melody evokes a festive ballroom, blending the elegance of a mazurka with the spirited bounce of a polka. Full of character and charm, this set offers a glimpse into Bizet’s early pianistic imagination.

L’arlesienne Suite No. 1

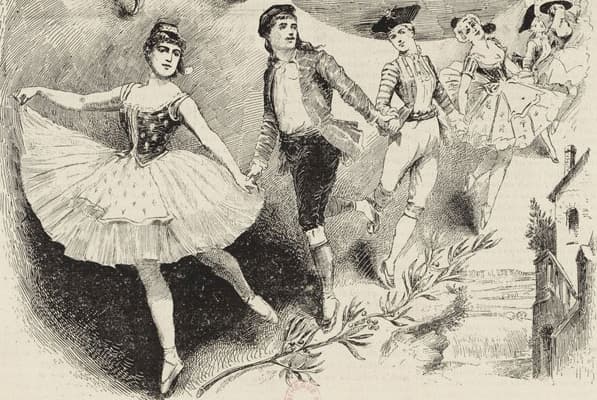

L’arlesienne

L’Arlésienne was originally composed as incidental music for Alphonse Daudet’s play. The music was later arranged into two orchestral suites, with the first dating from 1872 and the second arranged by Ernest Guiraud after Bizet’s death.

Bizet wrote the original music during a period of financial strain, and he infused the drama with vivid Provençal folk melodies and Romantic passion. While the play flopped, the suites gained lasting popularity. Some movements were transcribed for the piano, bringing their vibrant colours to the salon.

The Suite No. 1 bursts to life with the “Prélude,” and a march-like melody that evokes a festive procession under the Mediterranean sun. The “Minuetto” dances and swirls like a couple in an Arles ballroom, while the “Adagietto” is a heart-tugging gem. The concluding “Carillon” sparkles with bell-like clarity, evoking joy and festivity.

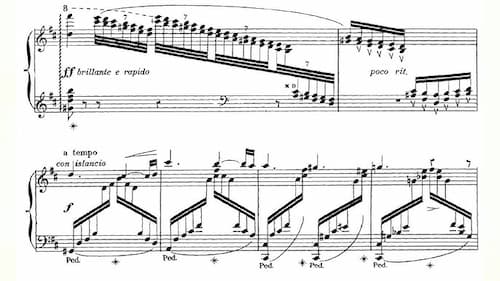

L’arlesienne Suite No. 2

The “Suite No. 2” was only compiled after Bizet’s death, and the piano transcription crafted for salon performers. The orchestral richness is adapted into accessible and evocative pieces. This version brought the vibrant colours of southern France to the salons of Paris.

The “Pastorale” rocks with a rolling melody that paints a sunlit landscape, with shepherds piping in the fields. Next, the “Intermezzo” shifts to a more dramatic tone, its expressive melody carrying a sense of longing and introspection.

The “Menuet” is actually borrowed from Bizet’s opera La Jolie Fille de Perth, and it dances with elegant charm, while the concluding “Farandole” explodes with infectious energy. The piano transcription captures the exuberance of this dance, leaving listeners swept up in a foot-stomping finale.

Nocturnes

Georges Bizet’s Nocturne in D Major

Living and working in Paris, it’s no surprise that Bizet would be in touch with piano nocturnes. I am sure he heard them and he played them, and he certainly composed two of his own. The Nocturne in F major dates from around 1854, when Bizet was 16 and studying at the Paris Conservatoire.

It features a lilting, almost dance-like melody that floats over soft and rolling chords. Moments of playful brightness are woven together with tender and reflective passages. It all builds to a gentle and luminous close, and this Nocturne offers a glimpse at Bizet’s precocious pianistic and compositional ability.

Although it was written fourteen years later in 1868, Bizet gave the Nocturne in D Major the No. 1. This Nocturne opens with a delicate and singing melody over a flowing and arpeggiated accompaniment. It evokes a sense of quiet introspection, with delicate trills and ornament echoing Chopin.

This piece is approachable for amateur pianists, and its emotional nuance can captivate listeners in any cosy salon setting. Both Nocturnes reflect the era’s love for lyrical and expressive piano music. Written for the salon audience, these pieces showcase Bizet’s early talent for crafting intimate and evocative music that balances technical accessibility with emotional warmth.

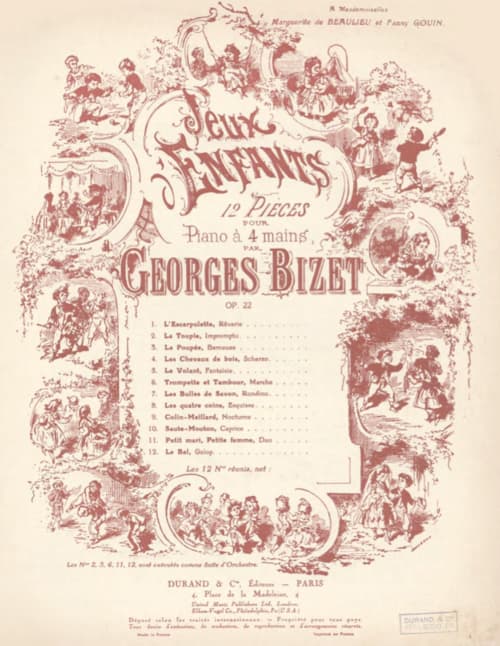

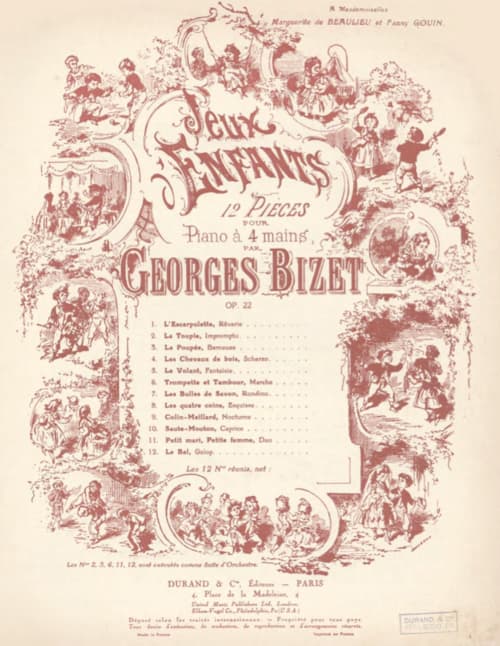

Jeux d’enfants

Georges Bizet’s Jeux d’enfants

If Georges Bizet composed a masterwork for piano, it might well have been Jeux d’Enfants (Children’s Games) for piano duets. Composed in 1871, this set of twelve delightful piano duets is not intended for children to play. Rather, these pieces capture the playful and innocent spirit of childhood.

Bizet included memories of his own childhood, intertwined with the joyful prospect of offspring and marital bliss. Although his son Jacques was born in 1872, Bizet never enjoyed the marital bliss he had hoped for, and he died only three years later.

Each of the twelve-character pieces has two titles. One is a children’s game, and the other is the musical form selected for it. “L’escarpolette” (The swing), for example, sounds like a sequence of opposing arpeggios that evokes gentle and dreamy rocking.

“La poupée” (The doll) is a lullaby, while the concluding “Le Bal” (The Ball) provides the suite with a fast and turbulent conclusion as a galloping dance. In 1872, Bizet orchestrated five pieces from this piano suite as the “Petite Suite.”

Youthful, Vivid, and Fun

The piano works by Georges Bizet reveal a youthful and versatile composer with a gift for vivid storytelling. Composed primarily in the 1850s and 60s, his pieces showcase his melodic charm and pianistic flair. Written for cultured salon audiences, these pieces blend playfulness, emotional warmth, and technical finesse that highlight Bizet’s versatile genius. And did I mention that they are really fun to play?