by

Being a composer is not a very – how could one put it delicately – commonsense profession. Many of history’s well-known composers were larger-than-life characters who earned idiosyncratic nicknames from their erratic and memorable behaviour. In this article, we take a look at how some of these gargantuan musical figures might have been known to their contemporaries.

Franz Schubert the Mushroom

Image created by ChatGPT

This composer’s musical stature far outstrips his literal stature – Schubert was only five-foot-one, or approximately 155 centimetres. This, in combination with his unusual face and rather pudgy physique, earned him the affectionate nickname “little mushroom” or “Schwammerl.” The composer also had high standards for those he socialised with, and he often asked early in the process of being introduced to someone, “Kann er was?” or “what can he do?” This earned him the nickname “Kanevas.”

Johannes Brahms, “Young Eagle”

Image created by ChatGPT

Robert Schumann gave Brahms an affectionate nickname as a token of his admiration for the composer’s abilities: “the young eagle.” This bird imagery likely came from the book of Revelations, which references “an eagle crying with a loud voice” (ESV), as Schumann had opined he “believe[d] Johannes to be the true Apostle, who will also write Revelations…” In addition to this admiring nickname, Schumann promoted Brahms’ music in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik magazine, founded by Schumann himself in 1834, and convinced Leipzig publishers to look at Brahms’ compositions.

Strangely, this avian imagery echoes elsewhere in his life, albeit less positively. Brahms once wrote about his own temperament: “I am a severely melancholic person…black wings are constantly flapping above us.”

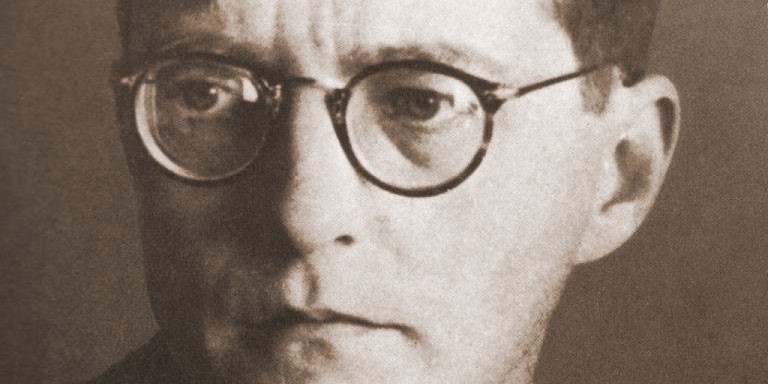

Joseph Haydn or “Papa Haydn”

Joseph Haydn

The nickname Haydn was given is a rare case study showcasing the power of words and the way linguistic meaning can change and be manipulated over time. Haydn was the Kapellmeister at the Esterházy court for over thirty years, presiding over a large group of much younger musicians. His benevolent attitude and willingness to stick up for the musicians of lesser status earned him the loving nickname “Papa Haydn.” As Clemens Höslinger notes, “’Papa’ arose as a term… for a father figure, someone who willingly gave advice and who was generally respected.” Eventually, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was among those who referred to Haydn as “Papa Haydn.”

The nickname grew even more popular in the 19th century as Haydn’s contributions to the symphonic and String quartet genres, and to music generally, became more broadly and formally codified. In 1797, the Tonkünstler-Societät of Vienna made Haydn an honorary life member “by virtue of his extraordinary merit as the father and reformer of the noble art of music.”

In the late 19th century, the nickname born of affection and reverence began to take on a caricatural, dismissive quality. “Papa Haydn” became a patronising and dismissive way to paint Haydn’s output as “genial, but naïve and superficial,” notes Höslinger. Recent scholarship has focused on providing a more nuanced picture of Haydn and his diversity and richness as a composer than the ideas that came to be associated with “Papa Haydn.”

Antonio Vivaldi: The Red Priest

Antonio Vivaldi

Gianbattista Vivaldi, Antonio Vivaldi’s father, was a famous Venetian violinist who regularly performed at St. Mark’s Basilica. Despite his son’s clear musical disposition, it was the local custom at the time for upper-class boys to be sent into the priesthood, and the young Antonio became a priest in 1703. This, in combination with his mop of naturally bright red hair, earned him the nickname “the red priest,” which stuck despite his relatively swift departure from the profession. Vivaldi the younger was too frail for the priestly vocation, and his true passion lay with music.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, or “Trazom”

Croce: Mozart Family Portait (detail), 1781

Fittingly, we end the list with the composer who sported the greatest variety of nicknames – and proper names – in his lifetime. Mozart was formally baptised in Latin as “Joannes Chrysostomus Wolfgangus Theophilus Mozart” on the 28th of January 1756, the day after his birth, at St. Rupert’s Cathedral in Salzburg.

Following the custom of the Catholic Church, Mozart’s first two names are drawn from the saint’s day of his birth, in this case St. John Chrysostom, “Chrysostomus” meaning “golden mouth.” “Wolfgang” came from Mozart’s maternal grandfather, and “Theophilus” from his paternal grandfather. Interestingly, “Theophilus” comes from Greek and means “lover of God” or “loved by God,” and it is from this that Mozart came to be called by the Latin version, “Amadeus,” or the German, “Gottlieb.”

Mozart worked across cultural borders and was linguistically flexible and very playful about his own name. As such, Mozart would toy with Italian and French, signing letters with “Amadeo” and “Amadé.” He loved to be facetious and would sign letters with purposefully incorrect Latin. Indeed, the popularity of referring to Mozart as “Wolfgang Amadeus” was a largely posthumous and Romantic-era trend, as Mozart never signed a single document “Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart” – the closest thing to this that survives in record being a silly mock-Latin signature, “Wolfgangus Amadeus Mozartus.” He also used his names backwards for fun: “Mozart Wolfgang” and “Trazom.”