After the extraordinary musical developments of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven the composition of a symphony became a daunting challenge, for many years the ultimate challenge for any composer. Many rose magnificently to that challenge, not least Brahms, Mahler, Sibelius and Shostakovich

As Richard Bratby notes in his article What is a Symphony?: 'Few musical terms carry such baggage. And to write a symphony, now as then, means engaging with Western music’s most ambitious ongoing attempt to create meaning out of sound; declaring to the world that you have something important to say – and are about to deploy all your creative powers to say it.'

We hope that the gathering of the 10 composers below serves as a informative introduction to the vast universe of symphonic writing, outlining the diverse ways that the greatest composers have responded to the task of writing a symphony, from the 18th century to the 20th. There are many outstanding symphonists to explore outside this initial list of 10 (Mendelssohn, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Dvořák, Copland, Carl Nielsen, Florence Price, Per Nørgård, Malcolm Arnold, John Adams – to name just a few), but we hope that this guide will set you off an an inspiring listening journey.

We have recommended both a complete symphony-cycle and a recording of an individual symphony for each composer.

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Haydn’s contribution to musical history is immense, he was nicknamed ‘the father of the symphony’ (despite Stamitz’s prior claim) and was progenitor of the string quartet. Like all his well-trained contemporaries, Haydn had a thorough knowledge of polyphony and counterpoint (and, indeed, was not averse to using it) but his music is predominantly homophonic. His 104 symphonies cover a wide range of expression and harmonic ingenuity.

Austro-Hungarian Haydn Orchestra / Adám Fischer (Brilliant Classics)

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791)

There is less than half a century between the death of Handel (1759) and the first performance of Beethoven’s Fidelio (1809). Bach and Handel were still composing when Haydn was a teenager. To compare the individual ‘sound world’ of any of these four composers is to hear amazingly rapid progress in musical thinking. Without doubt, the most important element of this was the development of the sonata and symphonic forms. During this period, a typical example generally followed the same basic pattern: four movements – 1) the longest, sometimes with a slow introduction, 2) slow movement, 3) minuet, 4) fast, short and light in character. Working within this formal structure, each movement in turn had its own internal structure and order of progress. Most of Haydn’s and Mozart’s sonatas, symphonies and chamber music are written in accordance with this pattern and three-quarters of all Beethoven’s music conforms to ‘sonata form’ in one way or another.

Mozart composed 41 symphonies and in the later ones (try the famous opening of No 40 in G minor) enters a realm beyond Haydn’s – searching, moving and far from impersonal.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Ludwig van Beethoven coupled his genius for music with profoundly held political beliefs and an almost religious certainty about his purpose. With the possible exception of Wagner, no other composer has, single-handedly, changed the course of music so dramatically and continued to develop and experiment throughout his entire career. His early music, built on the Classical paths trod by Haydn and Mozart, demonstrates his individuality in taking established musical structures and re-shaping them to his own ends. Unusual keys and harmonic relationships are explored, while as early as the Third Symphony (Eroica), the music is vastly more inventive and cogent than anything Mozart achieved even in a late masterpiece like the Jupiter. Six more symphonies followed, all different in character, all attempting new goals of human expression, culminating in the great Choral Symphony (No 9) with its ecstatic final choral movement celebrating man’s existence. No wonder so many composers felt daunted by attempting the symphonic form after Beethoven and that few ever attempted more than the magic Beethovenian number of nine.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

On March 26, 1828, in the Musikverein of Vienna, there was given for the first time a programme entirely devoted to Schubert’s music. It was put on by his friends, of course, but though successful, was never even reviewed. Less than eight months later, Schubert died of typhoid, delirious, babbling of Beethoven. He was 31 and was buried as near to him as was practicable, with the epitaph ‘Here lie rich treasure and still fairer hopes’. Schubert left no estate at all, absolutely nothing – except his manuscripts.

It was only by chance and the diligence of a few musicians that some of it came to light – in 1838 Schumann happened to visit Schubert’s brother and came across the great Symphony in C (the Ninth) and urged its publication; the Unfinished Symphony was not heard until 1865, after the score was found in a chest; it was George Grove (of Grove’s Dictionary fame) and the young Arthur Sullivan (of Gilbert and Sullivan fame) who unearthed in a publisher’s house in Vienna Schubert’s Symphonies Nos 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6, 60 songs and the music for Rosamunde. That was in 1867. Over a century later, in 1978, the sketches for a tenth symphony were unearthed in another Viennese archive.

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

‘I never had a more serious pupil than you,’ remarked Bruckner’s renowned teacher of counterpoint, Simon Sechter. Certainly, no one could ever accuse Bruckner of being frivolous and quite how this unsophisticated, obsequious boor came to write nine symphonies of such originality and epic splendour is one of music’s contradictions. You don’t turn to Bruckner the man or the musician for the light touch. His worship of Wagner verged on the neurotic for, really, there is something worrying about his debasement before the composer of Tristan. The dedication of his Third Symphony to Wagner reads: ‘To the eminent Excellency Richard Wagner the Unattainable, World-Famous, and Exalted Master of Poetry and Music, in Deepest Reverence Dedicated by Anton Bruckner’; before the two men eventually met, Bruckner would sit and stare at his idol in silent admiration, and after hearing Parsifal for the first time, fell on his knees in front of Wagner crying, ‘Master – I worship you’. His soliciting of honours, his craving for recognition and lack of self-confidence, allied with an unprepossessing appearance and a predilection for unattainable young girls, paints a disagreeable picture. The reverse of the coin is that of the humble peasant ill at ease in society, devoutly religious (most of his works were inscribed ‘Omnia ad majorem Dei gloriam’) and a personality of almost childlike simplicity and ingenuousness. God, Wagner and Music were his three deities.

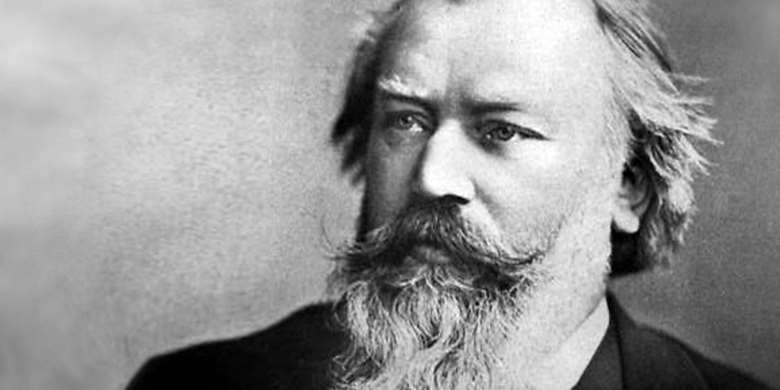

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Not all composers fell under Wagner’s spell. Brahms was the epitome of traditional musical thought. His four symphonies are far nearer the style of Beethoven than those of Mendelssohn or Schumann, and the first of these was not written until 1875, when Wagner had all but completed The Ring. Indeed Brahms is by far the most classical of the German Romantics. He wrote little programme music and no operas. It’s a curious coincidence that he distinguished himself in the very musical forms that Wagner chose to ignore – the fields of chamber music, concertos, variation writing and symphonies.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Mahler is the last great Romantic symphonist, music conceived on the grandest scale and employing elaborate forces. He wanted to express his view of the human condition, to set down his lofty ideals about Life, Death and the Universe. 'My symphonies represent the contents of my entire life.'

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

To most people Sibelius is the composer of Finlandia and the Karelia Suite; to others he is one of the great symphony composers; to the people of Finland he is these things and a national hero. While he was still alive the Finnish government issued stamps with his portrait and would have erected a statue to him as well had not Sibelius himself discouraged the project. Probably no composer in history has meant so much to his native country as did Sibelius. He still does. ‘He is Finland in music; and he is Finnish music,’ observed one critic.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Vaughan Williams emerged as an adventurous, unmistakably English composer with a distinct voice of his own. His discovery in the early 1900s of English folksong, through the recently formed English Folk Music Society, focused his style. VW and Gustav Holst, his lifelong friend whom he’d met at the Royal College, went out seeking the source of their country’s folksongs; many had never been written down before and the cataloguing and research that VW and Holst undertook in this area was of considerable cultural significance. His music now took on a different character. Apart from war service (for which he volunteered, although over 40), Vaughan Williams devoted the rest of his long life to composition, teaching and conducting.

Vaughan Williams worked on into old age with undiminished creative powers – his Eighth Symphony appeared in 1955 (the score includes parts for vibraphone and xylophone) while his Ninth, composed at the age of 85, uses a trio of saxophones.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Following his death, the government of the USSR issued the following summary of Shostakovich’s work, drawing attention to a ‘remarkable example of fidelity to the traditions of musical classicism, and above all, to the Russian traditions, finding his inspiration in the reality of Soviet life, reasserting and developing in his creative innovations the art of socialist realism and, in so doing, contributing to universal progressive musical culture’. The Times wrote of him in its obituary that he was beyond doubt ‘the last great symphonist’.

Thank you for visiting...

We have been writing about classical music for our dedicated and knowledgeable readers since 1923 and we would love you to join them.