by Frances Wilson February 4th, 2026

Girl playing the piano

The journey of learning to play the piano is a great deal more than the acquisition of a skill; it’s a wonderful voyage of memory and emotion. The memories of piano pieces learned during childhood or as students often linger in our minds – and indeed our fingers – creating a mosaic of experiences and memories that extend far beyond the piano keyboard.

As musicians, we can easily relate to this – the memories of those pieces – where we learned them, with whom, and who taught us – and these memories only deepen with time.

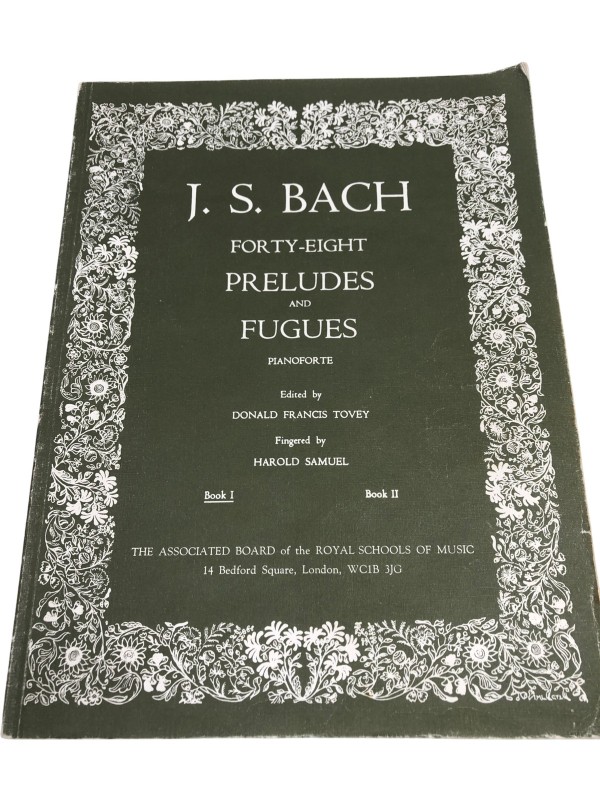

Music learned in our formative years often carries an emotional resonance that transcends the notes and rhythms. The melodies become intertwined with the memories of our youth, evoking nostalgia. These pieces serve as sonic bookmarks in the chapters of our lives, preserving the emotions felt during each practice session and performance. Looking back through old scores can create a “Proustian rush” of memories: my old ABRSM edition of Bach’s ‘48’, replete with my then teacher’s annotations, takes me back to piano lessons in the early 1980s, when I was an eager, precocious teenager. My then teacher had a big black Steinway grand in her living room, and her two dogs, a shaggy, rather smelly Old English Sheepdog, and a ginger spaniel, would sit under the piano’s belly as I played.

The process of learning and memorising piano pieces demands a high level of cognitive engagement. The brain forms intricate connections between motor skills, auditory processing, and memory recall during the practice and repetition required to master a piece. These cognitive networks established in childhood persist into adulthood, contributing to enhanced cognitive abilities, including improved memory, attention, and spatial-temporal skills. The act of memorisation itself becomes a mental exercise that strengthens neural pathways, leaving an indelible mark on our cognitive development.

Learning music involves acquiring a unique musical language. The ability to interpret and reproduce intricate patterns of sound develops a deep understanding of musical structures, harmonies, and phrasing. This early exposure to the language of music lays a foundation for future musical endeavours. Whether one continues to pursue a musical career or simply enjoys music as a listener, the memories of piano pieces learned in youth contribute to a lifelong appreciation and fluency in the language of music.

Piano pieces often serve as gateways to cultural and artistic heritage. Many students are introduced to classical compositions that have withstood the test of time, and which form what is known as the “core canon” of classical piano. The ability to play and internalise these timeless pieces connects one to a broader cultural context and fosters a sense of continuity with the past. These musical memories become part of one’s artistic identity, influencing not only how one perceives and engages with music but also how one expresses oneself creatively across various aspects of life.

The memories of piano pieces learned in childhood or as students persist not only as musical recollections but also as integral components of our cognitive, emotional, and creative selves. Woven into the fabric of our formative years, these memories accompany us through life, resonating with music’s unique ability to evoke emotions, enhance cognitive abilities, and contribute to our cultural and artistic identity.

As we navigate the symphony of life, the enduring melodies of our piano memories serve as a constant reminder of music’s transformative power.

Springtime – the turning of the season, the weather growing milder and the days longer, the first fresh buds of blossom appearing – is fertile territory for musical inspiration, as this selection of piano pieces inspired by Spring or emblematic of its reveal:

Springtime – the turning of the season, the weather growing milder and the days longer, the first fresh buds of blossom appearing – is fertile territory for musical inspiration, as this selection of piano pieces inspired by Spring or emblematic of its reveal: This piece was written for me as part of a project which paid homage to Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. 12 pieces were composed for 12 pianists who submitted their own recordings which were then mastered into an album. Although in a minor key, the mood of this piece, with its chirruping, pulsing rhythm and cascading arpeggios in the upper register of the piano, suggests nature bursting into life in all its colourful glory after the gloom of winter.

This piece was written for me as part of a project which paid homage to Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons. 12 pieces were composed for 12 pianists who submitted their own recordings which were then mastered into an album. Although in a minor key, the mood of this piece, with its chirruping, pulsing rhythm and cascading arpeggios in the upper register of the piano, suggests nature bursting into life in all its colourful glory after the gloom of winter.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.

Music has the power to tug at the heartstrings, and evoking emotion is the main purpose of music – whether it’s joy or sadness, excitement or meditation. A certain melody or line of a song, a falling phrase, the delayed gratification of a resolved harmony – all these factors make music interesting, exciting, calming, pleasurable and moving.