Maurice Ravel

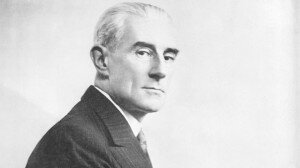

150 years ago, on 7 March 1875, the small village of Ciboure in the Basque region of France saw the birth of Maurice Ravel (1875-1937). Son of a Swiss engineer and a Basque mother, Ravel would become one of the most significant and innovative composers of the early 20th century, bridging the late Romantic tradition and the modernist impulses of his time.

Initially trained at the Paris Conservatoire, his music reflected a cosmopolitan sensibility, imbued with meticulous craftsmanship that earned him a reputation as a “musical jeweller.”

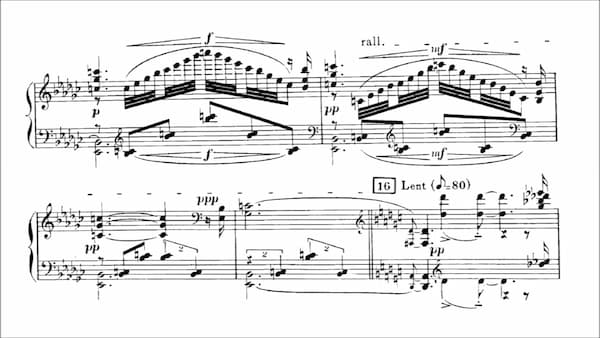

His oeuvre is characterised by its diversity and technical brilliance in a compositional style that often juxtaposes clarity and complexity. Revealing an almost obsessive attention to detail that frequently belies the effortless beauty of his melodies, Ravel’s music conveys a profound emotional restraint that often masks deeper sentiments beneath a polished surface.

As we celebrate his 150th birthday, we honour a composer whose masterful blend of innovation, emotional depth, and extraordinary craftsmanship forever shaped the landscape of classical music.

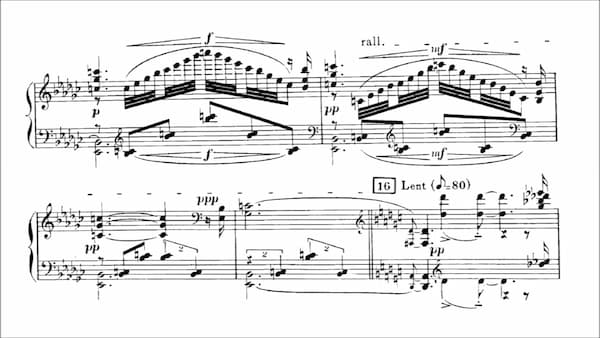

Maurice Ravel: Gaspard de la nuit

Formative Years

“Throughout my childhood,” Maurice Ravel once said, “I was sensitive to music. My father, much better educated in this art than most amateurs are, knew how to develop my taste and to stimulate my enthusiasm at an early age.” Maurice was deeply devoted to his mother, and his earliest memories involved her singing folk songs to him. He did not receive any formal schooling at an early age, but the family’s small apartment in Paris did house a piano.

Encouraged by his father, Maurice began piano lessons with Henry Ghys and soon demonstrated an extraordinary ear, improvising and composing small pieces even before formal training fully took hold. His teacher later recalled that “his conception of music is natural to him and not, as in the case of so many others, the result of effort.” By age 14, Ravel entered the Paris Conservatoire, initially as a piano student, but his true passion soon shifted toward composition.

Maurice Ravel: Shéhérazade

Formal Education

Ravel and his parents

Ravel’s relationship with the Conservatoire, according to scholars, “was marked by his independent spirit and refusal to adhere to its rigid expectations.” The young student found his inspiration outside of formal education, particularly from the 1889 Paris Exhibition and the cultural atmosphere of the time.

During these formative years, Ravel befriended fellow student Ricardo Viñes, a Spanish pianist who introduced him to Iberian music and avant-garde ideas, further broadening his horizons. He explored a wide range of musical and literary influences, including the works of composers like Satie, Debussy, and Chabrier, as well as writers such as Poe and Mallarmé. In fact, Ravel became part of a creative group called “Les Apaches” (The Hooligans) in the early 1900s, which fostered collaboration among artists, musicians, and writers.

Maurice Ravel: Rapsodie espagnole

First Performances

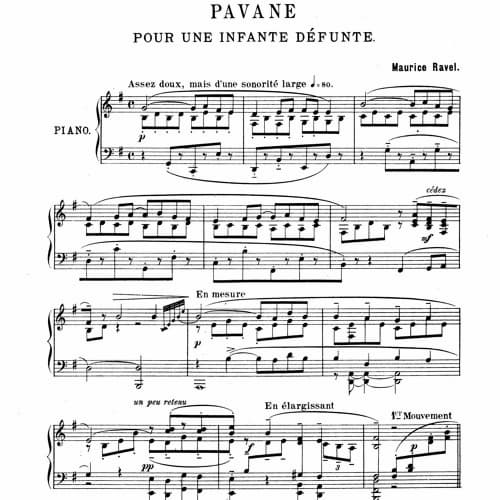

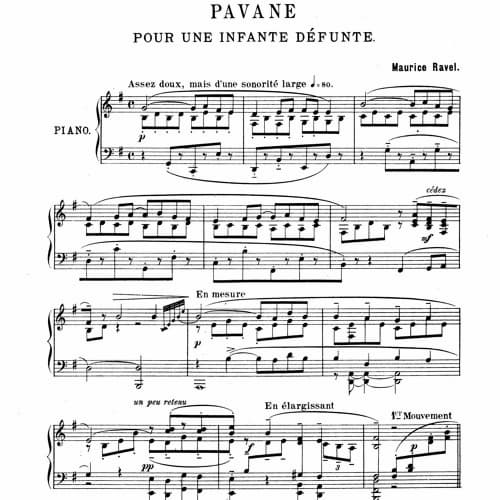

When Ravel conducted the first performance of his Shéhérazade overture in 1897, he was called a “mediocrely gifted debutant.” Two years later he composed his first piece to become widely known, the Pavane pour une infante défunte. One way or another, Ravel appeared calmly indifferent to blame or praise. The only opinion of his music that he truly valued was his own, as he was a “perfectionist and severely self-critical.”

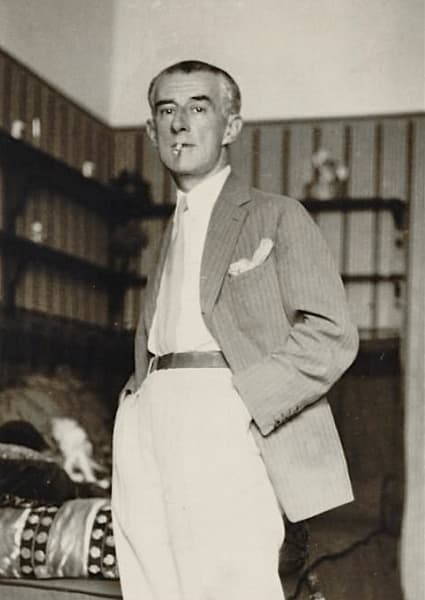

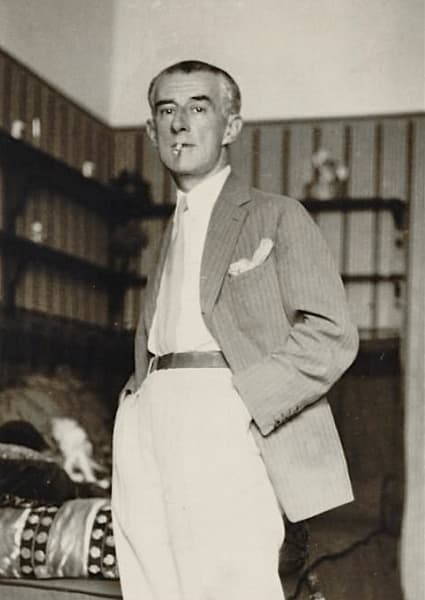

Maurice Ravel’s Sheherazade

At age 20, as biographer Burnett James reports, “Ravel was self-possessed, a little aloof, intellectually biased, and given to mild banter. He dressed like a dandy and was meticulous about his appearance and demeanour.” He continued to struggle at the Conservatoire, failing to secure the Prix de Rome despite multiple attempts between 1901 and 1905. However, his time there under Gabriel Fauré’s tutelage “honed his craft and instilled a lifelong devotion to clarity and refinement.”

Maurice Ravel: Pavane pour une infante défunte

International Reputation

By the early 20th century, Ravel had begun to distinguish himself in France with works like Jeux d’eau, a shimmering tour de force that showcased his innovative approach to texture and harmony. However, it was the premiere of his orchestral suite Daphnis et Chloé in 1912, commissioned by Serge Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes, that marked a turning point. This lush, expansive work, with its vivid orchestration and rhythmic vitality, captivated audiences and critics alike, and cemented Ravel’s status as a master of colour and narrative in music.

Maurice Ravel as a soldier in 1916

According to Roland-Manuel, Ravel was working on a Piano Trio when World War I broke out. In fact, Ravel was working on a number of projects, including a piano concerto based on Basque themes, two operas, a symphonic poem, and two major piano works. However, his compositional activity slowed significantly during the war, which he spent as a truck driver and ambulance assistant near the Verdun front. Suffering from exhaustion, dysentery, and the devastating loss of his mother in 1917, the war years left an indelible mark on his music and his psyche.

Maurice Ravel: Daphnis et Chloé “Suite No. 2”

After 1918

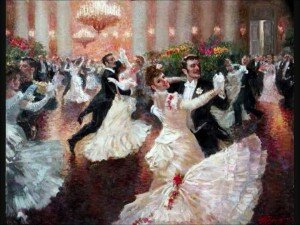

With the notable exception of Le Tombeau de Couperin, the effects of the war left a distinct toll on Ravel’s creativity. Amidst national and personal trauma, Ravel began to cloak his personal sorrow in refined artistry, which some commentators interpreted as a coping mechanism. Focusing on neoclassical restraint and dance forms, Ravel aimed for greater introspection and simplicity, as La Valse might well be read as a haunting commentary on a shattered Europe.

Maurice Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante defunte

After Debussy’s death in 1918, Ravel was regarded as France’s leading composers. He was officially recognised by the French state but publicly refused the Légion d’Honneur in 1920. His new-found celebrity also alienated him from some of his colleagues, particularly from Satie and some members of Les Six. As Barbara Kelly writes, “Ravel emphasised his isolation by moving 50km west of Paris, where he lived with his cats and was looked after by his housekeeper until his final illness.”

Maurice Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin

International Profile and Decline

Internationally, Ravel was celebrated as a modernist icon and he performed and lectured to packed houses in New York and Boston. American audiences were particularly enchanted by Boléro, which became a global sensation. His interactions with Stravinsky, Gershwin, and Vaughan William earned him accolades in England, Russia, and beyond, and his meticulous artistry and ability to fuse French elegance with universal appeal secured his place as a towering figure on the international musical landscape.

Maurice Ravel at the piano

By 1927, Ravel’s health had alarmingly deteriorated, and while he could still hear and compose music in his head, he gradually lost the ability to write it down. As he reported, “my mind is full of ideas, but when I want to write them down, they vanish.” Injured in a taxi accident in 1932, Ravel consulted a number of neurologists and underwent exploratory brain surgery. He died aged 62 in the early morning hours of 28 December 1937. The exact cause of Ravel’s death is still much debated, as are attempts to discover Ravel’s neurological decline in his later compositions.

Maurice Ravel: La Valse

Legacy

Ravel’s legacy as a composer is a testament to his singular ability to synthesise tradition and innovation. His meticulous craftsmanship, often likened to that of a watchmaker, produced a body of work that balances classical forms with a modernist sensibility, pushing harmonic and technical boundaries while retaining elegant coherence. His mastery of orchestration became a benchmark for further explorations of colour and texture in film music and beyond.

Ravel’s grave

Beyond specific compositional techniques, Ravel’s frequently veiled profound sentiment and emotional restraint beneath a highly polished surface, “evoking the universal through the particular.” By using cross-cultural influences woven into a distinct French idiom, Ravel is lauded as a precursor of a globalised aesthetic subsequently emerging in composers like Messiaen and Takemitsu. In the 21st century, Ravel remains a towering figure whose contributions continue to inspire and challenge the boundaries of musical expression.

One of his closest friends, the exceptional pianist Marguerite Long famously wrote, “Maurice Ravel is reserved, sacred, and distant with unwelcome visitors, yet he was the surest, most delicate, and most faithful of friends. By his exterior appearance, his witticisms, and his love of paradoxes, he has often contributed to crediting the myth of spiritual indifference, but, in spite of these appearances, this great prisoner of perfection hid a sensitive and passionate soul.”