Jazz, a catch-all term for a musical style that began to emerge from Black communities in the American South during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, revolutionized the international musical landscape around the turn of the century and beyond.

Jazz popularized musical ideas that would prove popular across multiple musical genres, including

- Syncopation (“the practice of displacing the beats or accents in music or a rhythm so that strong beats become weak and vice versa”)

- Swing (“to play music with an easy flowing but vigorous rhythm”)

- Blue notes (“a minor interval where a major would be expected”)

- Polyrhythm (“a rhythm which makes use of two or more different rhythms simultaneously”)

(All of those definitions come from Oxford Languages.)

© omniamericanfuture.org

Those four features are only scratching the surface of the traits that jazz provided to so-called “classical” composers, who, after the chaos of World War I, were looking for new musical languages to be inspired by.

Many of these composers drew profound inspiration from jazz and the blues, integrating elements of these genres into their own compositions.

Today, we’re looking at some prominent composers who incorporated jazzy influences into their works.

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel in 1925

Maurice Ravel was a French composer celebrated for his precise compositional technique and innovative orchestrations. He was fascinated by jazz.

His Violin Sonata, which he wrote between 1923 and 1927, has an entire middle movement called “Blues.”

Ravel’s contemporary, African-American composer and bandleader W. C. Handy, nicknamed The Father of the Blues, performed in Paris in the mid-1920s.

Ravel and his violinist friend Hélène Jourdan-Morhange, who was the dedicatee of this sonata, heard Handy and became inspired by his musical language.

Jazz continued to inspire Ravel, especially after he made a concert tour of America in 1928 and had the chance to hear more of it.

His 1931 Piano Concerto in G-major takes features of jazz, like syncopated rhythms and blue notes, and integrated them into the traditional concerto structure. The result was fresh, touching, and immediately engaging.

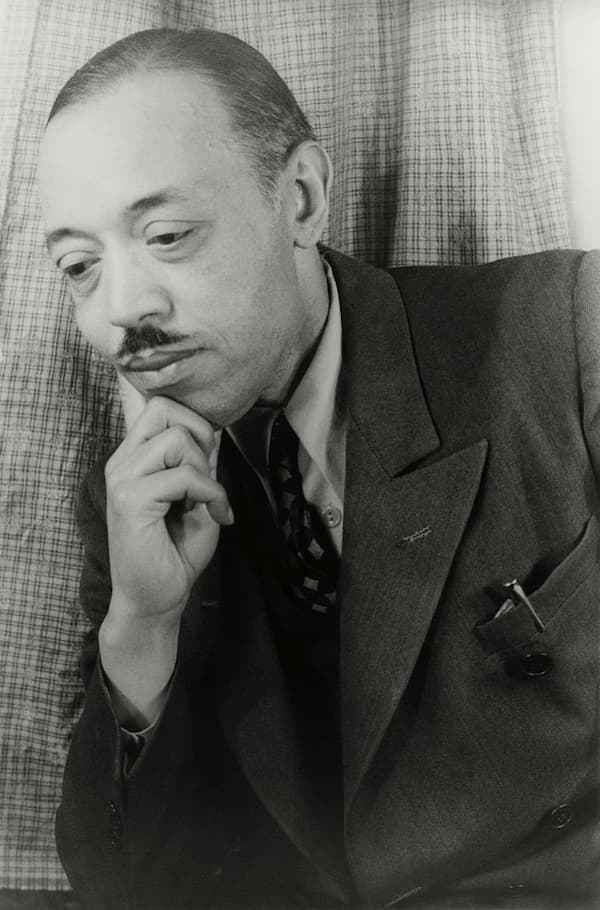

Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud (born in 1890) was another significant French composer who was influenced by jazz.

He heard his first jazz band – Billy Arnold’s Novelty Jazz Band – in London in 1920. He later wrote about them:

“Their constant use of syncopation in the melody was done with such contrapuntal freedom as to create the impression of an almost chaotic improvisation, whereas in fact, it was something remarkably precise.”

Later, in 1922, Milhaud took a trip to the United States and heard American jazz firsthand there.

Milhaud took these ideas and ran with them, composing his ballet La création du monde (The Creation of the World) between 1922 and 1923.

It merged an orchestral chamber ensemble and a jazz band into a six-part ballet lasting around eighteen minutes, utilizing saxophones, trumpets, and a rhythm section.

Igor Stravinsky

Igor Stravinsky

Russian-born composer Igor Stravinsky, who left Russia for other continental European cities after the Russian Revolution, also drew inspiration from jazz.

He began in the mid-1910s with his “Ragtime for 11 instruments” and continued exploring jazz influences for decades to come.

His “Ebony Concerto” from 1945 is a quintessential example of his jazz-influenced work. It was commissioned by clarinettist and big band leader Woody Herman, who led the First Herd band.

The band wasn’t used to playing music in Stravinsky’s style. Herman remembered later:

“After the very first rehearsal, at which we were all so embarrassed we were nearly crying because nobody could read, he walked over and put his arm around me and said, ‘Ah, what a beautiful family you have.’”

They all soldiered on. Saxophonist Flip Philips remembered:

“During the rehearsal…there was a passage I had to play there and I was playing it soft, and Stravinsky said ‘Play it, here I am!’ and I blew it louder and he threw me a kiss!”

This concerto took elements of classical form (the piece can be classified as a modern tongue-in-cheek interpretation of a Baroque concerto grosso) and combined those elements with jazz idioms, employing syncopated rhythms and swing.

George Gershwin

George Gershwin

George Gershwin is one of the composers who, being American and a popular songwriter, was most comfortable with weaving jazz into his “classical” compositions.

His “Rhapsody in Blue” (1924) for piano and orchestra is a landmark piece that blends the two genres.

The work’s famous opening clarinet glissando, lush harmonies, and rhythmic vitality are unmistakably inspired by the work of the era’s jazz bands.

Meanwhile, the use of the word Rhapsody (a type of free-flowing piece written by classical giants like Liszt, Dvořák, and Brahms), along with the concerto-like technical virtuosity required to play the solo part, paid tribute to influences from the “classical” world.

Gershwin’s ability to synthesise the improvisational spirit of jazz with classical structures turned him into one of the most successful jazz-inspired classical composers in the modern canon.

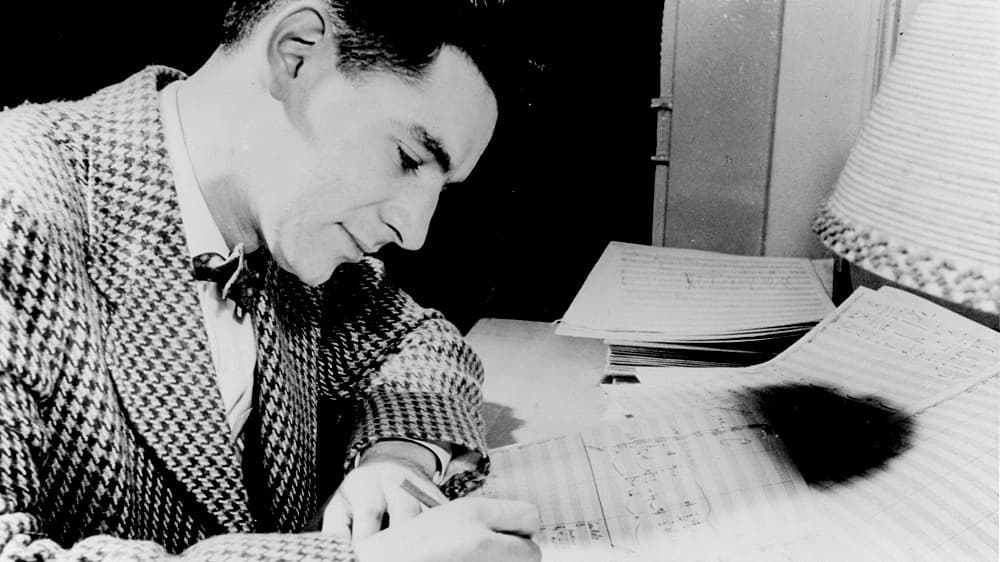

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland, 1946

Like Gershwin, Aaron Copland was American and incorporated jazz elements into many of his most popular works.

Copland’s “Music for the Theatre” (1925) and Piano Concerto are packed with jazz vibes.

In 1964, New York Philharmonic conductor Leonard Bernstein programmed during one of his famous televised New York Philharmonic Young People’s Concerts, and had Copland join him onstage to perform the solo part.

It was a reunion of sorts. Years before this performance, conductor and soloist had briefly been lovers, and their long-standing friendship and chemistry are certainly obvious in their joint advocacy of this 1926 concerto!

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein

Which brings us to Leonard Bernstein, a conductor, composer, and pianist who was deeply influenced by jazz.

His 1957 musical West Side Story employs jazzy rhythms and harmonies, particularly in songs like “Cool” and “Jet Song.”

His “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs” (written in 1949 for The Herd bandleader Woody Herman, the commissioner of Stravinsky’s “Ebony Concerto”) is another notable example, composed for a jazz ensemble and incorporating elements of swing and blues. (Unfortunately, Herman never got a chance to perform it, as The Herd disbanded in 1946.)eonard Bernstein was an enthusiastic believer in the universality of music. His fascination with bridging gaps between styles and genres in his compositions (and indeed, over the course of his career) provides a fascinating lens with which to view this music – and the broader history of the intersection of “jazz” and “classical music.”

William Grant Still

William Grant Still

Of course, the elephant in the room here is that jazz is a genre pioneered by Black Americans, and yet the most famous composers of jazz- or blues-inspired classical music are all white.

For many decades, as evidenced by just one glance at the whiteness of the established canon, Black composers have had trouble having their work taken as seriously as white composers.

This changed somewhat after 2020, but there is still a lot of work to be done.

Time will tell if organizations are serious about championing incredible works that have been sidelined because of the race of their composers.

One Black composer who incorporated jazz elements into his classical compositions was William Grant Still, who was born in 1895.

His brilliant “Afro-American Symphony” from 1930 draws especially heavily on the musical language of the blues.

Conclusion

Composers like Maurice Ravel, Darius Milhaud, Igor Stravinsky, George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, and William Grant Still were all inspired by rhythms, harmonies, and improvisational spirit of jazz and the blues. And these are only the most famous of hundreds of composers who, in some way or another, weaved jazz into their music.

Their works stand as testaments to the magic that can happen when the unnecessary boundaries between classical and popular music melt away, creating exciting new varieties of music.