By Georg Predota, Interlude

Works by Milhaud, Fleck, Van de Vate, O’Boyle, and Adams

Darius Milhaud: Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra

Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud writes, “I have always been very interested in percussion problems. In the Choéphores and in L’homme et son désir I used massive percussion. After the audition of Choéphores in Brussels, an excellent kettledrummer, Theo Coutelier, who had a percussion class in Schaerbeek near Brussels, asked me if I would like to write a concerto for a single percussion performer. The idea appealed to me, and this is how I came to compose the concerto. The school at Schaerbeek had only a few orchestral musicians, two flutes, two clarinets, one trumpet, one trombone, and strings.” Composed in Paris between 1929 and 1930, “jazz was enjoying a decisive influence on my musical composition. I wanted to avoid at all cost the thought that anyone might think of this work in a jazz way. I therefore stressed the rough and dramatic part of the piece. This was also why I did not write a cadence and always refused that anyone adds one.”

Milhaud’s Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra is a benchmark in the world of percussion. It is the first of its kind to utilize a multi-percussion setup that includes over twenty wood, metal, and membrane instruments performed by one player. Eager to avoid any references to the newly popular jazz genre, Milhaud dabbled in polytonality. If you listen carefully, you can hear the tonalities of C major, A minor, A major, and C-sharp minor sounding simultaneously. The concerto is cast in two sections titled “rude et dramatique”, and “modere.” The first features bi-tonal harmonies in the orchestra, while the second explores much more lyrical regions. The concert premiered at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1930.

Béla Fleck: Juno Concerto

Béla Fleck

Béla Anton Leoš Fleck, born in New York City in 1958, was named after his father’s favorite composers: Bartók, Webern, and Janáček. He played guitar in High School and took an interest in the French horn. However, when his grandfather brought home a secondhand banjo, it became an overwhelming obsession. The modern banjo—a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a circular resonator—is thought to have been derived from instruments used in the Caribbean and brought there from West Africa. Early instruments had a varying number of strings and used a gourd body and a wooden stick neck. The banjo is often associated with folk and country music, and it “occupied a central place in African-American traditional music and the folk culture of the rural South.” Fleck was always drawn to the instrument’s Bluegrass roots, and he became the world’s leading exponent of the banjo. In the process, Fleck has won at least 14 Grammy awards and produced an award-winning documentary exploring the banjo’s African roots.

A critic wrote, “Béla Fleck has taken banjo playing to some very unlikely places—not just bluegrass and country and “newgrass,” but also into jazz and the classical concerto.” To be sure, Fleck’s artistic pursuits have explored an astonishing variety of musical styles and traditions. And that includes the use of the banjo as a solo instrument together with a symphony orchestra. The “Juno Concerto” is actually Fleck’s second banjo concerto, and it was specifically written for his young son. The work unfolds in the customary 3 movements and features many elements expected in a concerto, including a number of dazzling cadenzas. A critic wrote, “the grandiose interplay between banjo and orchestra makes you wonder why banjos and orchestras aren’t sharing stages all the time.”

Nancy Van de Vate: Harp Concerto

Nancy Van de Vate

In the early 1970s, American composer Nancy Van de Vate explored the reasons why compositions by women simply did not appear on records. Among the reasons she cited were “a lack of university teaching positions held by or available to women, the lack of sufficient numbers of performances of their works, and the lack of commissions and prizes awarded to women.” In order to improve the situation, Van de Vate founded the “International League of Women Composers” to create and expand opportunities for women composers of music. That organization grew rapidly, and it evolved into the “International Alliance for Women in Music.” It currently “represents a diverse spectrum of creative specialization across genres within the music field and include composers, orchestrators, sound ecologists, performers, conductors, interdisciplinary artists, recording engineers, producers, musicologists, music librarians, theorists, writers, publishers, historian, and educators.”

Nancy Van de Vate also discovered that conventional titles like symphony, sonata, and concerto drew more attention in composition competitions requiring anonymous submissions. Judges and panelists were influenced by the titles ascribed to particular works, and many of her own compositions, therefore, use traditional titles. Her large orchestral works, however, have very descriptive titles such as “Journeys,” “Dark Nebulae,” and “Chernobyl.” Her Harp Concerto dates from 1996 and was first performed on 21 June 1998 with the Moravian Philharmonic in Olomouc. The harp, it seems, was rediscovered in the 20th century, and together with Ginastera, Glière, Jongen, Milhaud, Jolivet, Rautavaara, Rodrigo, and Villa-Lobos, Van de Vate contributed to a growing repertoire for that instrument in the concerto genre.

Sean O’Boyle/William Barton: Concerto for Didgeridoo

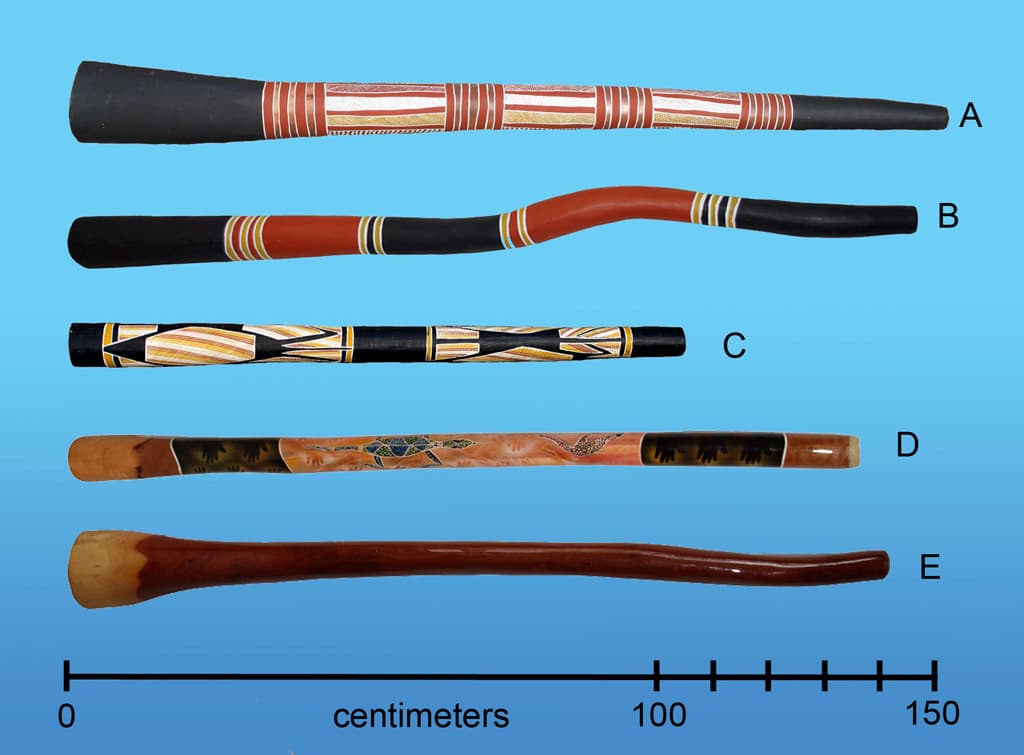

Australian didgeridoos

The didgeridoo, called by different names in various cultures, is a wooden drone pipe played with varying techniques in a number of Australian Aboriginal cultures. While the historical origin of the instrument is uncertain, Aboriginal mythology ascribed it to the power of creating dreams. The instrument is generally fashioned from the termite-hollowed trunks or branches of a number of trees. The sound of the didgeridoo is considered the voice of the ancestral spirit of that tree, and it is always stored upright to keep the ancestral spirit safe. The didgeridoo can produce a blown fundamental pitch “and several harmonics above the fundamental.” Basically, a performer does not blow air into the instrument. The distinctive buzzing tone is produced by the continual buzzing of the lips, with the shape of the mouth, tongue, cheeks, chin, and teeth influencing the tone quality. Didgeridoo performers have perfected the technique of circular breathing, “in which the player reserves small amounts of air in the cheeks or mouth while blowing. This allows the player to snatch frequent small breaths through the nose while simultaneously continuing the drone pitch by expelling the reserved air.”

William Barton © Keith Saunders

The buzzing sound of the didgeridoo has become an easily recognizable icon of Aboriginal Australia. Contemporary bands and culturally hybrid world music groups have adopted that colorful instrument, and a number of Australian composers have used the instrument in chamber works. In addition, the legendary player William Barton collaborated with Sean O’Boyle to bring the didgeridoo into the concert hall. The work showcases the incredible expressive power of the instrument, and Barton writes, “The didgeridoo is a language. It is a speaking language. And like any language, it’s something that you’ve got to learn over many months and many years. It’s got to be a part of you and what you do.”

John Adams: Concerto for Electric Violin and Orchestra

Walt Disney Concert Hall

To celebrate the opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2002, then LA Phil’s music director Esa-Pekka Salonen approached John Adams for a work to inaugurate the venue. When Adams looked at the artist’s rendition of the unfinished building, he was struck “by the sweeping, silver-toned clouds and sails of its exterior, and its warm and inviting public spaces.” In his composition, Adams wanted to “reflect the experience of those who, like me, were not born here and for whom the arrival on this side of the continent had both a spiritual and physical impact.” Originally, Adams was looking to incorporate a spoken part for the narrator, and searching for a suitable California-based text, discovered Jack Kerouac’s novel Big Sur. That novel celebrates the California spirit, and Adams “realized that what I had to say was something that could only be expressed in music.”

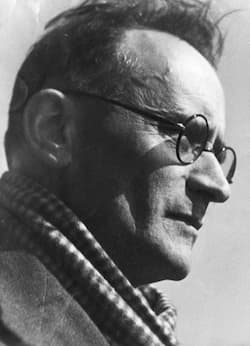

John Adams and Tracy Silverman

During the genesis of his Concerto for Electric Violin and Orchestra, Adams heard violinist Tracy Silverman perform in a jazz club. “When I heard Tracy play,” he writes, “I was reminded that in almost all cultures other than the European classical one, the real meaning of the music is in between the notes. The slide, the portamento, and the “blue note” all are essential to the emotional expression… Tracy’s manner of playing was a fusion of styles that showed a deep knowledge of a variety of musical traditions.” After collaborating with Silverman, Adams wrote a part for electric violin “that evokes the feeling of free improvisation while the utmost detail is paid to both solo and instrumental parts, all written out in precise notation.” For Adams, The Dharma at Big Sur expresses the “so-called shock of recognition, when one reaches the edge of the continental land mass… For a newcomer, the first exposure produces a visceral effect of great emotional complexity. I wanted to compose a piece that embodied the feeling of being on the West Coast, literally standing on the precipice overlooking the geographic shelf with the ocean extending far out into the horizon.”