It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, November 10, 2024

O Holy Night - JOSLIN LIVE with the IRVING SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

Friday, June 21, 2024

Unique Concertos

By Georg Predota, Interlude

Works by Milhaud, Fleck, Van de Vate, O’Boyle, and Adams

Darius Milhaud: Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra

Darius Milhaud

Darius Milhaud writes, “I have always been very interested in percussion problems. In the Choéphores and in L’homme et son désir I used massive percussion. After the audition of Choéphores in Brussels, an excellent kettledrummer, Theo Coutelier, who had a percussion class in Schaerbeek near Brussels, asked me if I would like to write a concerto for a single percussion performer. The idea appealed to me, and this is how I came to compose the concerto. The school at Schaerbeek had only a few orchestral musicians, two flutes, two clarinets, one trumpet, one trombone, and strings.” Composed in Paris between 1929 and 1930, “jazz was enjoying a decisive influence on my musical composition. I wanted to avoid at all cost the thought that anyone might think of this work in a jazz way. I therefore stressed the rough and dramatic part of the piece. This was also why I did not write a cadence and always refused that anyone adds one.”

Milhaud’s Concerto for Percussion and Small Orchestra is a benchmark in the world of percussion. It is the first of its kind to utilize a multi-percussion setup that includes over twenty wood, metal, and membrane instruments performed by one player. Eager to avoid any references to the newly popular jazz genre, Milhaud dabbled in polytonality. If you listen carefully, you can hear the tonalities of C major, A minor, A major, and C-sharp minor sounding simultaneously. The concerto is cast in two sections titled “rude et dramatique”, and “modere.” The first features bi-tonal harmonies in the orchestra, while the second explores much more lyrical regions. The concert premiered at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1930.

Béla Fleck: Juno Concerto

Béla Fleck

Béla Anton Leoš Fleck, born in New York City in 1958, was named after his father’s favorite composers: Bartók, Webern, and Janáček. He played guitar in High School and took an interest in the French horn. However, when his grandfather brought home a secondhand banjo, it became an overwhelming obsession. The modern banjo—a stringed instrument with a thin membrane stretched over a circular resonator—is thought to have been derived from instruments used in the Caribbean and brought there from West Africa. Early instruments had a varying number of strings and used a gourd body and a wooden stick neck. The banjo is often associated with folk and country music, and it “occupied a central place in African-American traditional music and the folk culture of the rural South.” Fleck was always drawn to the instrument’s Bluegrass roots, and he became the world’s leading exponent of the banjo. In the process, Fleck has won at least 14 Grammy awards and produced an award-winning documentary exploring the banjo’s African roots.

A critic wrote, “Béla Fleck has taken banjo playing to some very unlikely places—not just bluegrass and country and “newgrass,” but also into jazz and the classical concerto.” To be sure, Fleck’s artistic pursuits have explored an astonishing variety of musical styles and traditions. And that includes the use of the banjo as a solo instrument together with a symphony orchestra. The “Juno Concerto” is actually Fleck’s second banjo concerto, and it was specifically written for his young son. The work unfolds in the customary 3 movements and features many elements expected in a concerto, including a number of dazzling cadenzas. A critic wrote, “the grandiose interplay between banjo and orchestra makes you wonder why banjos and orchestras aren’t sharing stages all the time.”

Nancy Van de Vate: Harp Concerto

Nancy Van de Vate

In the early 1970s, American composer Nancy Van de Vate explored the reasons why compositions by women simply did not appear on records. Among the reasons she cited were “a lack of university teaching positions held by or available to women, the lack of sufficient numbers of performances of their works, and the lack of commissions and prizes awarded to women.” In order to improve the situation, Van de Vate founded the “International League of Women Composers” to create and expand opportunities for women composers of music. That organization grew rapidly, and it evolved into the “International Alliance for Women in Music.” It currently “represents a diverse spectrum of creative specialization across genres within the music field and include composers, orchestrators, sound ecologists, performers, conductors, interdisciplinary artists, recording engineers, producers, musicologists, music librarians, theorists, writers, publishers, historian, and educators.”

Nancy Van de Vate also discovered that conventional titles like symphony, sonata, and concerto drew more attention in composition competitions requiring anonymous submissions. Judges and panelists were influenced by the titles ascribed to particular works, and many of her own compositions, therefore, use traditional titles. Her large orchestral works, however, have very descriptive titles such as “Journeys,” “Dark Nebulae,” and “Chernobyl.” Her Harp Concerto dates from 1996 and was first performed on 21 June 1998 with the Moravian Philharmonic in Olomouc. The harp, it seems, was rediscovered in the 20th century, and together with Ginastera, Glière, Jongen, Milhaud, Jolivet, Rautavaara, Rodrigo, and Villa-Lobos, Van de Vate contributed to a growing repertoire for that instrument in the concerto genre.

Sean O’Boyle/William Barton: Concerto for Didgeridoo

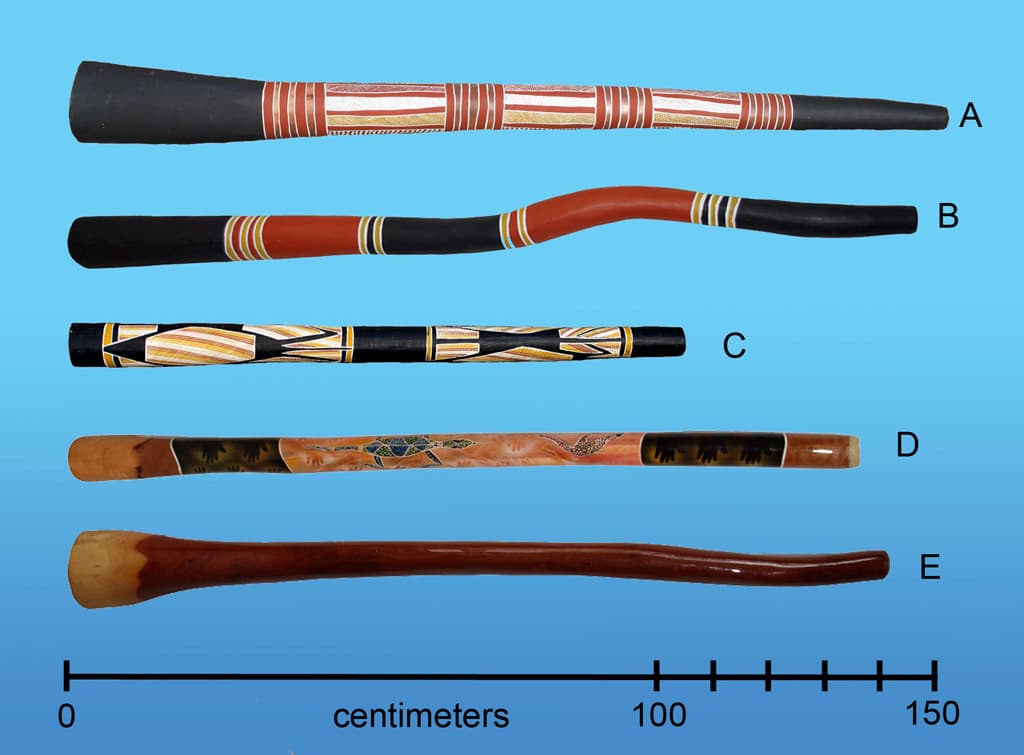

Australian didgeridoos

The didgeridoo, called by different names in various cultures, is a wooden drone pipe played with varying techniques in a number of Australian Aboriginal cultures. While the historical origin of the instrument is uncertain, Aboriginal mythology ascribed it to the power of creating dreams. The instrument is generally fashioned from the termite-hollowed trunks or branches of a number of trees. The sound of the didgeridoo is considered the voice of the ancestral spirit of that tree, and it is always stored upright to keep the ancestral spirit safe. The didgeridoo can produce a blown fundamental pitch “and several harmonics above the fundamental.” Basically, a performer does not blow air into the instrument. The distinctive buzzing tone is produced by the continual buzzing of the lips, with the shape of the mouth, tongue, cheeks, chin, and teeth influencing the tone quality. Didgeridoo performers have perfected the technique of circular breathing, “in which the player reserves small amounts of air in the cheeks or mouth while blowing. This allows the player to snatch frequent small breaths through the nose while simultaneously continuing the drone pitch by expelling the reserved air.”

William Barton © Keith Saunders

The buzzing sound of the didgeridoo has become an easily recognizable icon of Aboriginal Australia. Contemporary bands and culturally hybrid world music groups have adopted that colorful instrument, and a number of Australian composers have used the instrument in chamber works. In addition, the legendary player William Barton collaborated with Sean O’Boyle to bring the didgeridoo into the concert hall. The work showcases the incredible expressive power of the instrument, and Barton writes, “The didgeridoo is a language. It is a speaking language. And like any language, it’s something that you’ve got to learn over many months and many years. It’s got to be a part of you and what you do.”

John Adams: Concerto for Electric Violin and Orchestra

Walt Disney Concert Hall

To celebrate the opening of Walt Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles in 2002, then LA Phil’s music director Esa-Pekka Salonen approached John Adams for a work to inaugurate the venue. When Adams looked at the artist’s rendition of the unfinished building, he was struck “by the sweeping, silver-toned clouds and sails of its exterior, and its warm and inviting public spaces.” In his composition, Adams wanted to “reflect the experience of those who, like me, were not born here and for whom the arrival on this side of the continent had both a spiritual and physical impact.” Originally, Adams was looking to incorporate a spoken part for the narrator, and searching for a suitable California-based text, discovered Jack Kerouac’s novel Big Sur. That novel celebrates the California spirit, and Adams “realized that what I had to say was something that could only be expressed in music.”

John Adams and Tracy Silverman

During the genesis of his Concerto for Electric Violin and Orchestra, Adams heard violinist Tracy Silverman perform in a jazz club. “When I heard Tracy play,” he writes, “I was reminded that in almost all cultures other than the European classical one, the real meaning of the music is in between the notes. The slide, the portamento, and the “blue note” all are essential to the emotional expression… Tracy’s manner of playing was a fusion of styles that showed a deep knowledge of a variety of musical traditions.” After collaborating with Silverman, Adams wrote a part for electric violin “that evokes the feeling of free improvisation while the utmost detail is paid to both solo and instrumental parts, all written out in precise notation.” For Adams, The Dharma at Big Sur expresses the “so-called shock of recognition, when one reaches the edge of the continental land mass… For a newcomer, the first exposure produces a visceral effect of great emotional complexity. I wanted to compose a piece that embodied the feeling of being on the West Coast, literally standing on the precipice overlooking the geographic shelf with the ocean extending far out into the horizon.”

Thursday, November 23, 2023

Adolphe Charles Adam - his music and his life

Adolphe Charles Adam ; 24 July 1803 – 3 May 1856) was a French composer, teacher and music critic. A prolific composer for the theatre, he is best known today for his ballets Giselle (1841) and Le corsaire (1856), his operas Le postillon de Lonjumeau (1836) and Si j'étais roi (1852) and his Christmas carol "Minuit, chrétiens!" (Midnight, Christians, 1844, known in English as "O Holy Night").

Adam was the son of a well-known composer and pianist, but his father did not wish him to pursue a musical career. Adam defied his father, and his many operas and ballets earned him a good living until he lost all his money in 1848 in a disastrous bid to open a new opera house in Paris in competition with the Opéra and Opéra-Comique. He recovered, and extended his activities to journalism and teaching. He was appointed as a professor at the Paris Conservatoire, France's principal music academy.

Together with his older contemporary Daniel Auber and his teacher Adrien Boieldieu, Adam is credited with creating the later Romantic French form of opera.

Life and career

Adam was born in Paris on 24 July 1803, the elder of the two children, both sons, of (Jean) Louis Adam and his third wife, Élisa, née Coste. She was the daughter of a prominent physician, and was a former pupil of her husband, a well-known composer, pianist and professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Louis Adam gave his son lessons, but the boy was reluctant to learn even the basics of musical theory, and instead played fluently by ear:

I loved music, but I didn't want to learn it. I would sit quiet for hours, listening to my father play the piano, and as soon as I was alone I tapped on the instrument without knowing my notes. I knew without realising it how to find the harmonies. I didn't want to do scales or read music; I always improvised.

He later said that he never became a fluent sight-reader of a score. His mother concluded that her son needed a rigorous education, and he was sent to a boarding school, the Hix institute in the Champs-Élysées. It had a high reputation both academically and musically: his elder contemporary (and pupil of Louis Adam) Ferdinand Hérold had been educated there, and the music master was Henry Lemoine, another of Louis' former students. Adolphe was not an academic child, and recalled in his memoirs how he had recoiled from the study of Latin, which he found "barbaric". The fall of the French Empire in 1814–15, and the ensuing economic problems badly affected Louis Adam's income, and to save money his son was sent to a less expensive school. The staff there were capable, but Adam remained as indifferent to musical theory as to Latin.

At the age of 17 Adam enrolled at the Conservatoire, where he studied the organ with François Benoist, counterpoint with Anton Reicha and composition with Adrien Boieldieu. Adam's biographer Elizabeth Forbes calls Boieldieu the chief architect of Adam's musical development. He set his student exercises that taught him to compose sustained melodies without showy modulations and other technical devices.Adam's father did not want his son to become a professional composer: he would have preferred him to pursue a commercial or academic career, and although he gave Adam board and lodging he refused to subsidise any musical activities. By the age of 20 Adam was contributing songs to the Paris vaudeville theatres, writing what he later called "bad romances and worse piano pieces", and giving music lessons.

Duchaume, timpanist and chorus master of the new Théâtre du Gymnase, offered Adam an unpaid post playing the triangle in the orchestra. Adam said that as he would have paid to be allowed to join he was happy to serve without a salary, but he was quickly promoted to a well paid position:

My entry to the Gymnase was an event in my life. I made acquaintances and friendships with actors and writers; that was, in a word, my starting point. Duchaume died, and I succeeded him as timpanist and chorus master, at a salary of six hundred francs a year. It was a fortune. I no longer gave thirty-sous lessons, and I wrote a little less trashy music.

In 1824 Adam entered the Conservatoire's most important musical competition, the Prix de Rome. He gained an honourable mention, and the following year, at his second attempt, he won the second prize. Forbes writes that Adam derived more benefit from helping Boieldieu with the preparation of his opera La Dame blanche, produced at the Opéra-Comique in December 1825. Adam's piano transcriptions of themes from the opera were published in 1826 and made him enough money to tour the Netherlands, Germany and Switzerland in summer 1826 with a family friend, Sébastien Guillié. In Geneva he met the librettist Eugène Scribe, with whom he later collaborated on nine stage works.

During 1824–1827 Adam wrote or arranged the music for several one-act vaudevilles given at the Gymnase and the Théâtre du Vaudeville, including four written by Scribe as sole or co-author. In late 1827 Scribe provided the text for Adam's first opera, a one-act comic piece, Le Mal du pays, ou La Batelière de Brientz (Homesickness, or the Bargewoman of Brientz), comprising an overture and eleven numbers; it was produced at the Gymnase on 28 December 1827. A little over a year later, in February 1829, Adam's second one-act opera, Pierre et Catherine was given in a double bill at the Opéra-Comique with Auber and Scribe's La Fiancée, and ran for more than 80 performances.

Seven months after the premiere of Pierre et Catherine Adam married Sara Lescot, a member of the chorus at the Vaudeville. Adam's biographer Arthur Pougin describes the marriage as "an important and unfortunate event for him".By Pougin's account, Lescot manoeuvred Adam into marriage, and on his side – and later hers also – it was a loveless union; they separated in 1835. Their only child, Léopold-Adrien, born in 1832, killed himself in 1851.

Adam's first full length operas were premiered in 1829: Le jeune propriétaire et le vieux fermier and Danilowa, opéras comiques given at the Théâtre des Nouveautés and the Opéra-Comique respectively. Danilowa ran well until Parisian life was disrupted by the July Revolution. That, and an outbreak of cholera, led Adam to move to London; this was at the suggestion of his brother-in-law, Pierre François Laporte, manager of the King's Theatre, Haymarket. In 1832 Laporte leased the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and in October, as an afterpiece to The Merchant of Venice, he presented James Planché's His First Campaign, a "Military Spectacle" about the Duke of Marlborough, with music by Adam. The piece was received with "loud and general plaudits", but The Dark Diamond, a historical melodrama in three acts, which followed on 5 November, failed to repeat its success, and Adam went home to Paris in December. He returned briefly to London when his ballet Faust was presented at the King's Theatre in February and March 1833.

In 1834 Adam had one of his greatest popular successes with Le chalet, at the Opéra-Comique. This was a one-act opéra comique with words by Scribe and Mélesville based on Goethe's Jery und Bätely. It was given more than 1000 times in Paris over the next four decades. In May 1836 Adam was appointed as a chevalier of the Legion of Honour, later promoted to officer of the order. His first work for the Paris Opéra was a ballet, La fille du Danube, introduced by Marie Taglioni in September 1836.Within days of the premiere of that piece, his three-act opéra comique Le postillon de Lonjumeau opened successfully at the Opéra-Comique. It was the composer's greatest operatic success internationally, quickly taken up by foreign managements and seen in London in 1837 and New York in 1840.

During 1838 and 1839 Adam composed the music for Les Mohicans, a ballet for the Opéra, and four operas for the Opéra-Comique, and in September 1839 he left Paris for St Petersburg. His ballet for Taglioni, L'Écumeur de mer (The Pirate) was given before the imperial court in February 1840, and two of his operas were staged. He left Russia for Paris at the end of March, stopping off in Berlin, where he wrote an opera-ballet, Die Hamadryaden (The Tree Nymphs), which he conducted at the Court Opera in April 1840.

Adam's next substantial work was the composition by which he has become best known: the ballet Giselle. Based on Heinrich Heine's version of an old tale, the ballet premiered at the Opéra on 28 June 1841 with Carlotta Grisi in the title role. Adam continued his prolific output, including his first grand opera, Richard en Palestine, which was produced at the Opéra in 1844 but aroused little interest. In that year he was elected to membership of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Financial disaster

In 1845 François-Louis Crosnier, director of the Opéra-Comique, resigned and was succeeded by Alexandre Basset. Basset soon fell out with Adam and told him that as long as he was director, Adam's works would never be performed at the Opéra-Comique.[Early in 1847 a theatre in the Boulevard du Temple became available, and Adam, in partnership with the actor Achille Mirecour, took it over, rechristening it the Opéra-National. The cost of refurbishing the theatre was enormous, and in addition to investing his own money, Adam raised large sums in loans. The new opera house opened in November 1847, but from the outset its prospects looked doubtful. Financial and artistic performance alike were poor, and the 1848 Revolution was the final blow to the enterprise. The theatres were closed by the incoming régime, and when they were permitted to re-open, there was little demand for tickets at Adam's opera house, which closed on 28 March 1848, after the production of nine operas during its four months of existence, leaving him financially ruined.

Adam assigned the royalties from his earlier works to help pay off his debts, and like many other French composers in need of money he turned to journalism to earn extra income. He contributed reviews and articles to Le Constitutionnel and the Assemblée nationale. He also became a teacher, accepting the post of professor of composition at the Conservatoire, where his students included Léo Delibes.Meanwhile, Basset having left the Opéra-Comique at the time of the revolution, Adam was able to return to what Forbes calls his spiritual home under its new director, Émile Perrin.

Last years

In July 1850 Giralda, ou La nouvelle psyché – one of Adam's best operas in Forbes's view – was given at the Opéra-Comique. In 1851 his estranged wife died, and Adam married the singer Chérie-Louise Couraud (1817–1880), with whom he lived for his remaining years.For the Théâtre-Lyrique, the revived incarnation of his failed Opéra-National, Adam wrote the successful Si j'étais roi, first given in September 1852. In that year he produced six new works, enabling him to clear all his debts.

During the last three years of his life Adam continued to compose prolifically. His late works include what Forbes rates as one of his finest ballets, Le Corsaire, based on a poem by Byron; it was presented at the Opéra in January 1856, after a year's preparation. His final stage work, the one-act opérette Les Pantins de Violette (Violette's Puppets) was given at the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens on 29 April 1856. Four nights later Adam died in his sleep, at the age of 52. He was buried in the Montmartre Cemetery.

In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Forbes writes that much of Adam's prolific output was ephemeral. This includes the many popular numbers he wrote for vaudevilles in his early years, a large number of piano arrangements, transcriptions and potpourris of favourite operatic arias, and numerous light songs and ballads. Nonetheless, "there remain several operas and ballets that are not merely delightful examples of their kind, but are also scores full of genuine inspiration". In this category Forbes includes Le chalet (which incorporates music from the cantata he wrote for the 1825 Prix de Rome competition) which she ranks with Adam's best works for its freshness of invention. For the musicologist Theodore Baker, Adam ranks with Auber and Boieldieu as one of the creators of French opera, thanks to the expressive power of his melodic material and his keen sense of dramatic development.

In France, during Adam's lifetime and beyond, Le chalet was his most popular opera. In other countries the favourite was Le postillon de Lonjumeau. In Germany in particular the opera was celebrated for its tenor aria "Mes amis, écoutez l'histoire" (given in translation as "Freunde, vernehmet die Geschichte"), with its demanding high D. Grove comments that the opera has distinctive and well characterised roles and a sense of theatre, found in all Adam's operas. Of the later operas, Grove singles out Giralda and Si j'étais roi as "the most stylish, tuneful and accomplished".

Although he was a prolific composer of opera, Adam wrote ballet music even more fluently. He commented that it was fun, rather than work. Giselle is the best known; Baker calls it a major work in the history of choreography, which continues to be performed with the same success. Forbes comments that although Giselle has the advantage of a particularly memorable plot, La jolie fille de Gand, La filleule des fées and Le corsaire are of equal quality musically.

Little of Adam's religious music has entered the regular repertory, with the exception of his Cantique de Noël, "Minuit, chrétiens!", known in English as "O Holy Night".

Adam's memoirs were published posthumously, in two volumes: Souvenirs d'un musicien (1857) and Derniers souvenirs d'un musicien (1859).