by Emily E. Hogstad

It’s the month when Beethoven’s Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were heard for the first time in a freezing Viennese hall – the month when Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker dazzled St. Petersburg audiences – and the month when Bach’s Christmas Oratorio first stunned Leipzig churchgoers on Christmas Day.

The Nutcracker with Charlotte Nebres as Clara, 2019 (photo by Erin Baiano / New York City Ballet)

It’s also the month that saw the birth of Maria Callas, Jean Sibelius, and Olivier Messiaen…as well as the death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose death on 5 December 1791 marked one of the greatest losses in the history of music.

Today, we’re looking at some of the most important December anniversaries in classical music history.

1 December 1944

Premiere of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra

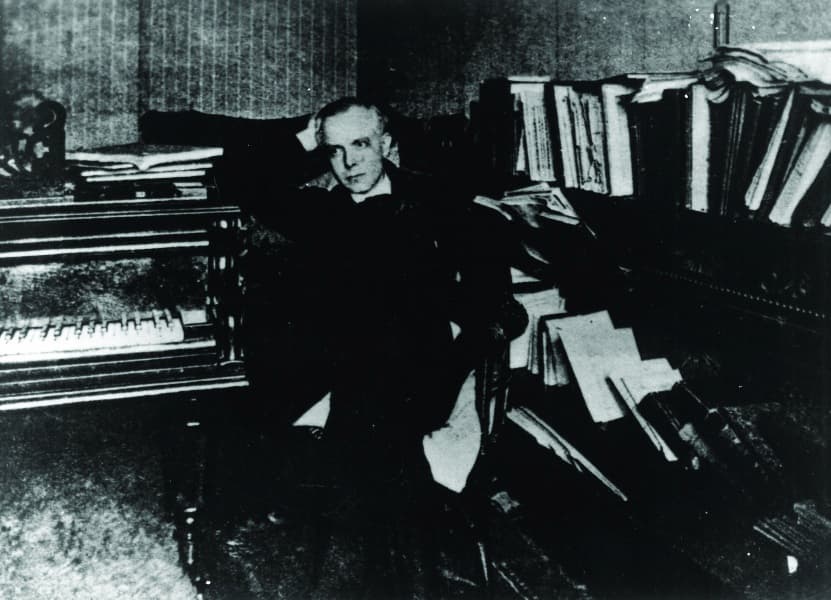

Béla Bartók

This Concerto for Orchestra by exiled composer Béla Bartók first burst to life in Boston on this day in 1944.

World war was raging, and Bartók was terminally ill. Yet despite that, Bartók succeeded in creating one of the greatest musical masterpieces of the twentieth century.

We wrote an article about Bartók’s heartbreaking final illness and the conditions under which he wrote the Concerto.

2 December 1923

Birth of Maria Callas

Maria Callas sings an excerpt from Norma

Born in New York to Greek parents, Maria Callas grew up to become the operatic diva of the twentieth century, making countless classic recordings and inspiring multiple biopics.

We wrote an article about the obstacles Maria Callas overcame in her life, including her turbulent love life, a fraught relationship with her mother, and a painful battle with her weight.

3 December 1721

Marriage of Johann Sebastian Bach and Anna Magdalena Wilcke Bach

Excerpts from Bach’s Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach

When he was 36, Johann Sebastian Bach wed the gifted young court soprano Anna Magdalena Wilcke, who was 20.

So began a personal and professional partnership that would shape classical music history for centuries to come.

Anna Magdalena Bach

We wrote here about what happened to the thirteen (!) children born during their marriage, as well as the surviving children from Bach’s first marriage.

4 December 1881

Premiere of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto was a bit of a flop when it made its Vienna debut on this day in 1881, but nowadays it’s one of the most beloved concertos ever written, for any instrument.

We wrote here about the secret gay love affair that helped to inspire the concerto after Tchaikovsky’s disastrous marriage.

5 December 1791

Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Mozart’s short, incandescent life ended in Vienna when he was just 35 years old. His unfinished Requiem would be his final work.

Henry Nelson O’Neil: The Last Hours of Mozart, 1860s

We went into the details of how Mozart’s health deteriorated and what it was like at his deathbed.

6 December 1933

Birth of Henryk Górecki

Born in a poor Silesian village in 1933, Górecki would grow up to become a major composer.

His Symphony of Sorrowful Songs became a blockbuster hit in the 1970s. We wrote about the extraordinary story behind the symphony, and how it accidentally became a classic.

7 December 1842

First concert of the Philharmonic Society of New York

In early December 1842, the Philharmonic Society of New York launched what would become America’s oldest symphony orchestra, today known as the New York Philharmonic.

8 December 1865

Birth of Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius grew up to create the sound world of an entire nation: his beloved Finland.

His musical portrayals of snowy horizons and fierce defiance, colored by moments of triumph and tragedy, are unforgettable.

Jean Sibelius, 1923

Find out how Sibelius grew into Finland’s greatest composer.

9 December 1745

Birth of Maddalena Laura Lombardini Sirmen

A Venetian violin virtuosa trained by the famous Baroque violinist Giuseppe Tartini, Lombardini Sirmen composed and toured Europe to acclaim, proving that an eighteenth-century woman could hold her own against the composers and soloists of her day.

Her first violin concerto was praised by none other than Mozart’s father.

We wrote an article with thirteen intriguing facts about Lombardini Sirmen’s life and music.

10 December 1908

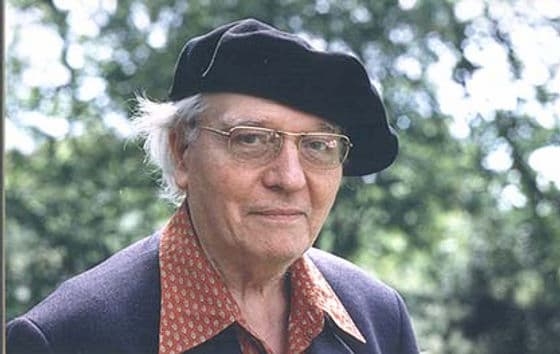

Birth of Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Messiaen

French composer Olivier Messiaen wrote timeless music that incorporates birdcalls, a veritable rainbow of instrumental colours, and his staunch Catholic faith into radiant soundscapes.

We wrote a beginner’s guide to Messiaen.

11 December 1803

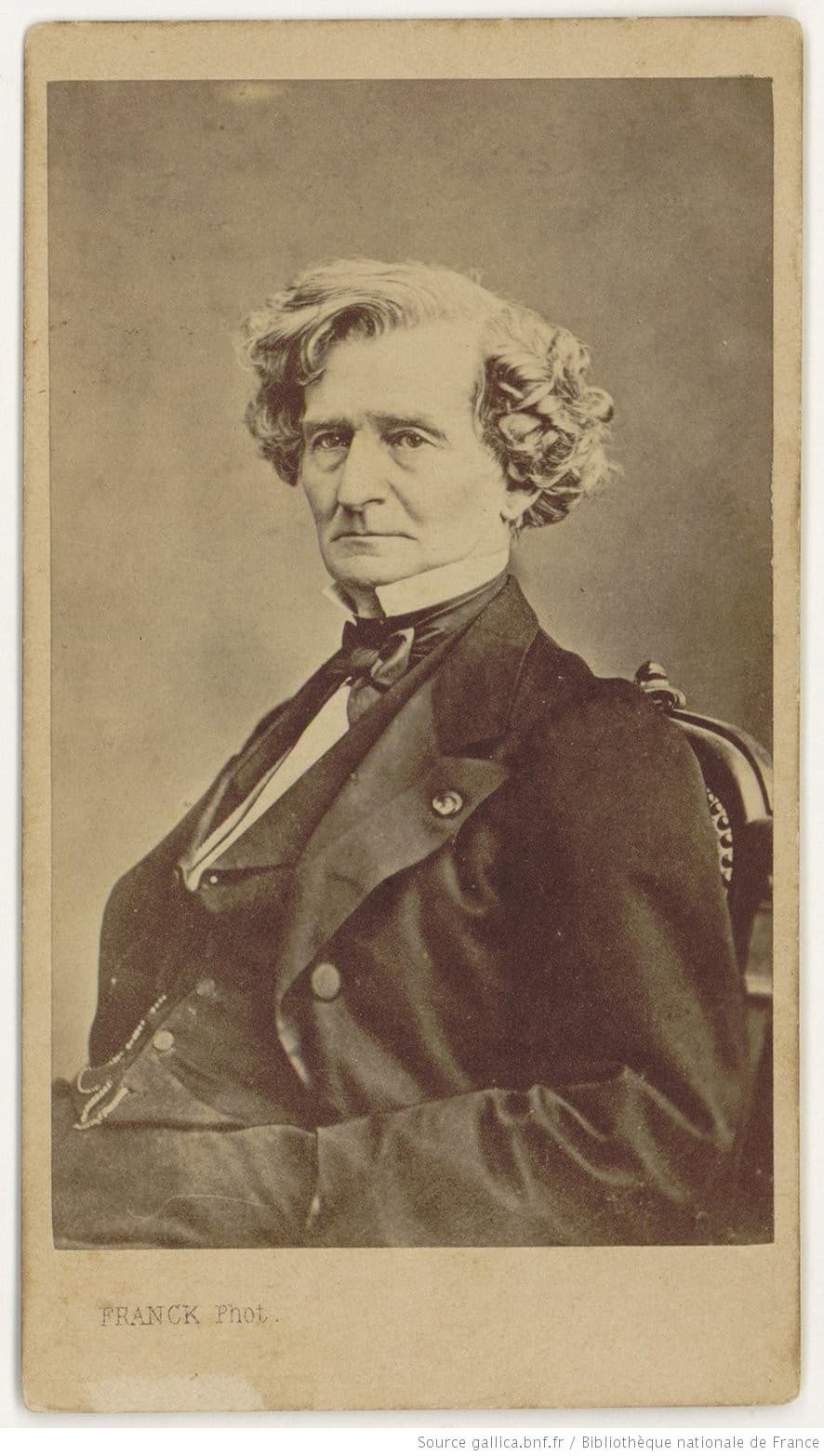

Birth of Hector Berlioz, La Côte-Saint-André

Franck: Hector Berlioz, 1860s (Gallica, ark:/12148/btv1b84542182)

Hector Berlioz was born in provincial La Côte-Saint-André, France.

His groundbreaking orchestration and dramatic storytelling helped shape the Romantic Era, and his terrifying obsession with actress Harriet Smithson gave birth to his famous Symphonie fantastique.

We looked at why Berlioz was considered to be such a rebellious enfant terrible.

12 December 1891

Premiere of Johannes Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet

Johannes Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet, Op. 115 is one of his final and most introspective works: a bittersweet masterclass in melancholy.

We looked at a performance of Brahms’ Clarinet quintet by the Jerusalem Quartet and clarinettist Sharon Kam.

13 December 1812

Death of Marianna Martines

Viennese composer Marianna Martines died on this day at age 63.

A student of Haydn and admired by Mozart, she was one of the few women composers to gain recognition in eighteenth-century Vienna.

We looked at Marianna Martines’s extraordinary life story and how she was able to compete with the great male composers in her orbit.

14 December 1789

Birth of Maria Szymanowska

Maria Szymanowska

Maria Szymanowska was a pioneering concert pianist and composer whose distinctly Polish style anticipated the idiom of poetic pianism later perfected by Chopin.

We explained here why Maria Szymanowska was so ahead of her time, and why Goethe called her “a great talent bordering on madness.”

15 December 1924

Birth of Ida Haendel

Haendel plays the Sibelius violin concerto

Violinist Ida Haendel was born in Chelm, Poland, on this day in 1924.

A child prodigy who debuted with a number of major orchestras before she turned ten, she sustained one of the longest classical music careers of the century.

She credited her survival of World War II to her musical talents.

We celebrated Ida Haendel and her trademark big hair and high heels.

16 December 1882

Birth of Zoltán Kodály

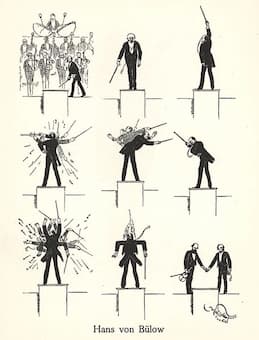

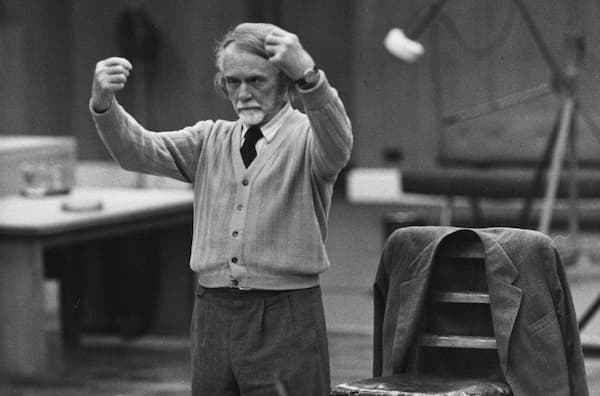

Zoltán Kodály conducting

Composer and educator Zoltán Kodály was born in Kecskemét, Hungary, on this day in 1882.

Renowned for his choral works and passion for music education, he helped shape Hungary’s modern musical identity, and his pedagogical ideas are still widely embraced today.

Learn more about Kodály’s childhood.

17 December 1770

Baptism of Ludwig van Beethoven

Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7

Ludwig van Beethoven was baptised in Bonn. We observe the date of his baptism because we don’t know for sure which day he was born, although many people believe it would have been December sixteenth.

Of course, we all know that he became the most influential composer of his generation!

We looked at the story of Beethoven’s tragic childhood, and how he survived disturbing parental abuse.

18 December 1892

Premiere of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker ballet

The Nutcracker

Tchaikovsky’s ballet The Nutcracker and opera Iolanta premiered as a double bill at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg in 1892, the year before his death.

Both works quickly became staples of the repertoire.

We wrote about The Nutcracker’s premiere and why it is helping to ensure future classical music audiences.

19 December 1888

Birth of Fritz Reiner

Conductor Fritz Reiner was born in Budapest in 1888.

His controlling precision on the podium helped to define the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s sound during his tenure there as music director…and made him a few enemies along the way.

We wrote an article discussing Reiner’s rocky relationship with his principal cellist János Starker.

20 December 1948

Birth of Mitsuko Uchida

Mitsuko Uchida plays Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20

Japanese pianist Mitsuko Uchida was born in Tokyo on this day in 1948.

Celebrated for her insightful interpretations of Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven, she is one of today’s leading interpreters of the classical canon.

We wrote an article about Uchida’s childhood and how she became so passionate about the piano.

21 December 1953

Birth of András Schiff

Pianist and conductor András Schiff was born in Budapest on this day in 1953.

Known for his thoughtful musicianship and deep commitment to Bach and Beethoven, he remains one of the most respected pianists of his generation.

We wrote about why András Schiff is one of the greatest pianists of all time.

22 December 1808

Premieres of Beethoven’s Symphonies No. 5 and No. 6, Piano Concerto No. 4, and Choral Fantasy

During Christmas break in 1808, at Vienna’s luxurious Theater an der Wien, Beethoven conducted a marathon concert featuring the premieres of his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, the Fourth Piano Concerto, and the Choral Fantasy—all in a single evening.

It is likely the most famous concert in classical music history.

We looked at how Beethoven pulled off this multi-hour monster concert.

23 December 1893

Premiere of Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel

Engelbert Humperdinck’s opera Hänsel und Gretel premiered in Weimar under the baton of composer Richard Strauss. The work became an enduring Christmas favourite.

We wrote about what makes Hänsel und Gretel this Christmas classic so charming.

24 December 1835

Birth of Cosima Liszt Wagner

Richard Wagner and Cosima von Bülow Wagner

Cosima Liszt, daughter of Franz Liszt and later wife of Richard Wagner, was born on Lake Como on Christmas Eve in 1835.

She would become the formidable custodian of Wagner’s legacy at Bayreuth, and although she wasn’t a composer herself, one of the most influential women in nineteenth and even twentieth-century music.

Find out the unforgettable way that Wagner celebrated Cosima’s birthday in style in 1870.

25 December 1734

Premiere of Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, Part I

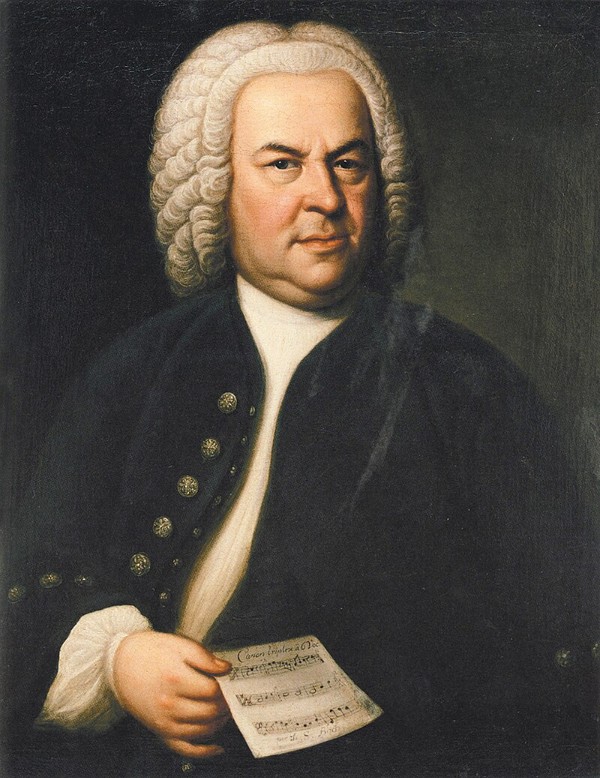

Elias Gottlob Haussmann: J.S. Bach, 1746 (Leipzig: Bach-Archiv)

J

The first part of Bach’s six-part Christmas Oratorio was premiered in Leipzig in 1734.

This first part celebrates the birth of Jesus.

26 December 1926

Premiere of Sibelius’s Tapiola

One of Jean Sibelius’s final orchestral masterpieces, Tapiola, premiered in New York in 1926.

The work’s haunting soundscape reflected the composer’s imminent – and infamous – soft retirement, which would last for decades, until the end of his life.

We wrote an article called Ten Pieces to Make You Love Sibelius.

27 December 1944

Death of Amy Beach

Amy Beach

Trailblazing American composer Amy Beach was best known for her Gaelic Symphony (the first woman-written symphony ever played by a major American orchestra) and numerous gorgeous piano works.

We wrote about Amy Beach’s fascinating life – and her staggering early genius.

28 December 1916

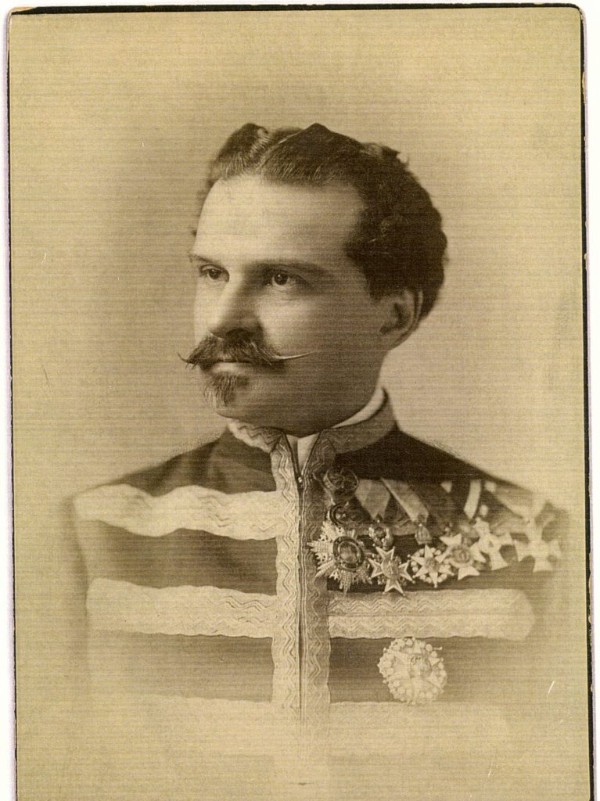

Death of Eduard Strauss

Eduard Strauss

Eduard Strauss, the younger and last-surviving brother of Johann Strauss II, died at age 81.

His passing marked the end of the original Strauss family line of waltz composers.

We told the story of the wildly dysfunctional Strauss family dynasty.

29 December 1876

Birth of Pablo (Pau) Casals

Cellist Pablo Casals was born in El Vendrell, Catalonia.

His firm stance against twentieth-century fascism and his revival of Bach’s Cello Suites made him a moral as well as musical icon.

We wrote about why it was a miracle that Casals survived his childhood.

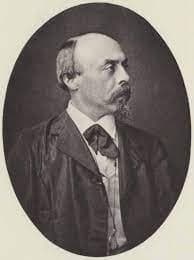

30 December 1904

Birth of Dmitry Kabalevsky

Dmitry Kabalevsky

Soviet composer Dmitry Kabalevsky was born in St. Petersburg on this day in 1904.

He became known for his accessible style and dedication to music education during the Soviet era.

31 December 1962

Birth of Jennifer Higdon

A Pulitzer and Grammy winner, Jennifer Higdon is one of the most frequently performed American composers of the twenty-first century.

Back in 2019 we talked with her about her string quartet Voices appearing at the Intimacy of Creativity festival.

Conclusion

From Bach’s Christmas Oratorio to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, December is filled with classical music anniversaries that changed the course of music history.

The month brings together composer birthdays, landmark premieres, and tragic deaths.

Each and every anniversary is an opportunity to remember how rich the legacy of the art is…and how much it has to give to future generations.

What do you find to be the most meaningful December anniversary in classical music history?