by Georg Predota, Interlude

Anton Webern

Throughout his short life—having been accidentally shot by an American soldier in 1945—the music of Anton Webern (1883-1945) was almost totally unknown. With the end of WWII, however, the musical world was in need of revitalization and eagerly adopted Webern’s compositional style. His music began to serve as an often-imitated model, and Igor Stravinsky accessed Webern’s influence in 1960. “Of course the entire world had to imitate him, and of course it would fail miserably. Webern was simply too original, too purely himself to worry about the limits of his appeal. Nothing composed since can diminish his strength nor stale his perfection.” The cool and constructive side of Webern’s music, in which economy and extreme concentration reign supreme, provided the stimulus for young composers gathered for holiday courses in new music in the German city of Darmstadt. Hailed as the father of a completely fresh musical movement, Webern’s ideas spawned musical experimentations throughout the world. Webern’s music is inherently poetic, and his uncompromising determination to pursue a new aesthetic established a novel musical syntax entirely his own.

Anton Webern, 1912

One of the great innovative voices of 20th century music, Anton Webern was born in Vienna. His father was a mining engineer, and his mother a competent pianist and accomplished singer. His father’s career brought the family to the provincial capitals of Graz and Klagenfurt, where Webern learned the rudiments of music theory and took piano lessons. He also took cello lessons and played in the local orchestra.

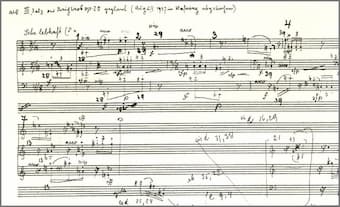

Sketch of Webern

His first compositions, 2 Pieces for Cello and Piano, and several songs date from this period. After graduation, his father rewarded him with a trip to Bayreuth and the operas of Wagner left a deep impression on the young musician. In 1902, Weber matriculated at the University of Vienna, studying musicology under Guido Adler and eventually submitting a dissertation on the Dutch composer Heinrich Isaac. Meanwhile in 1904, Webern became a student of Arnold Schoenberg at the University of Vienna. He progressed quickly under Schoenberg’s tutelage, and he became close friends with fellow student Alban Berg.

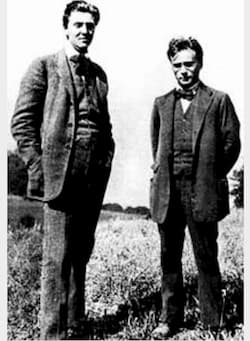

Arnold Schoenberg, Otto Klemperer, Hermann Scherchen, Anton Webern and Erwin Stein

Webern’s formal study with Schoenberg ended in 1908, and although he only composed the first two opus numbers during his time of apprenticeship, all of Webern’s subsequent works show a clear influence and deep reverence for Schoenberg. In the years following their apprenticeship, both Berg and Webern worked for Schoenberg during this crucial time in the master’s creative life. They copied parts, made piano reductions and produced numerous arrangements for both his private and professional life. Between 1908 and 1913, Webern took up short-lived posts as coach and conductor, but he loathed the theatre routine and preferred to focus on his creative work. His compositions had been increasingly atonal, but with his settings of poetry by Stefan George, Webern embarked on a novel stylistic direction. Extreme conciseness of form is buttressed by melodic and harmonic fragmentation, wide intervallic leaps, complex cross-rhythms, unusual use of dissonance and timbre resulting in shimmering and quickly changing tone colors.

Alban Berg and Anton Webern

Webern briefly served during World War I but was discharged because of poor eyesight. Unable to secure an academic appointment, he settled on the outskirts of Vienna and began to devote his time to private teaching, conducting and composition. When Schoenberg formulated the 12-tone method of composition, Webern quickly adopted the system and wrote to Berg, “12-tone composition is for me now a completely clear procedure.” He would employ the serial technique for all further compositions, “and developed it with severe consistency to its most extreme potential.”

Anton Webern, ca 1940

Webern was not politically active, but he fell victim to the rising tide of right-wing nationalism. Schoenberg left Europe in 1933, and with Berg’s death in 1935 Webern’s isolation was complete. He music was branded “degenerate art” and performances and publications banned in Germany and Austria. When his son Peter was killed during military service in 1945, Webern and his wife fled to the town of Mittersill in the mountains near Salzburg. Four months after the war had ended, Webern was shot while smoking a cigar on the veranda of his daughter’s house, indirectly the victim of his son-in-law’s black market activities. Webern’s music, to quote the scholar Julian Johnson, “is characterized by an ungraspability of surface, with melodic outlines distributed in a texture of pointillist color, timbre and angularity. Below this seemingly fractured surface, however, his music is organized strictly in accordance with contrapuntal rules that provide the structural frame. For a new generation of composers, including Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Webern’s music “was the cornerstone and model for an entirely new epoch.”