by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

It wasn’t always this way, though. Today we’re looking at seven times when classical music audiences became unruly…and what upset them so much!

1. The Barber of Seville by Gioachino Rossini

Rossini’s The Barber of Seville

20 February 1816 in Rome

Nowadays, we aren’t terribly familiar with composer Giovanni Paisiello, but back in the early nineteenth century, he was a respected rival of Gioachino Rossini.

In 1782, Paisiello wrote an opera called Il barbiere di Siviglia (The Barber of Seville). It was based on a libretto by Giuseppe Petrosellini, which in turn was based on a book by famed creative Frenchman Pierre Beaumarchais.

This opera turned out to be the biggest success of Paisiello’s entire career.

In 1815, Gioachino Rossini also looked to Beaumarchais for inspiration and decided to write his own adaptation of The Barber of Seville. (At least he used a different libretto from Paisiello.)

Obviously, audiences raised an eyebrow: it felt like an attack on beloved Paisiello.

Rossini’s version of Barber premiered in Rome in February 1816, and disaster ensued. There was hissing and jeering through the whole thing (some of it paid for by Paisiello’s allies). To add insult to injury, accidents started happening onstage, too.

However, fortunately for Rossini, the next night’s performance went smoother. Rossini’s Barber of Seville began gaining popularity. (For a long time, though, Paisiello’s was more popular.)

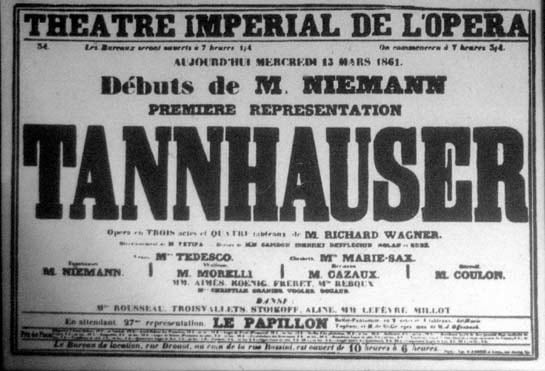

2. Tannhäuser by Richard Wagner

Poster of Tannhäuser performance in Paris

14 March 1861 in Paris

The premiere of Tannhäuser occurred in 1845.

Sixteen years later, in 1861, a performance of Tannhäuser was scheduled in Paris at the Paris Opéra.

This was such an important event that Wagner rewrote the original to conform to Parisian tastes and rules. (For example, operas at the Opéra traditionally had ballet sequences.)

However, instead of inserting the ballet in the second act, as was customary, Wagner wrote it into the story during the first act.

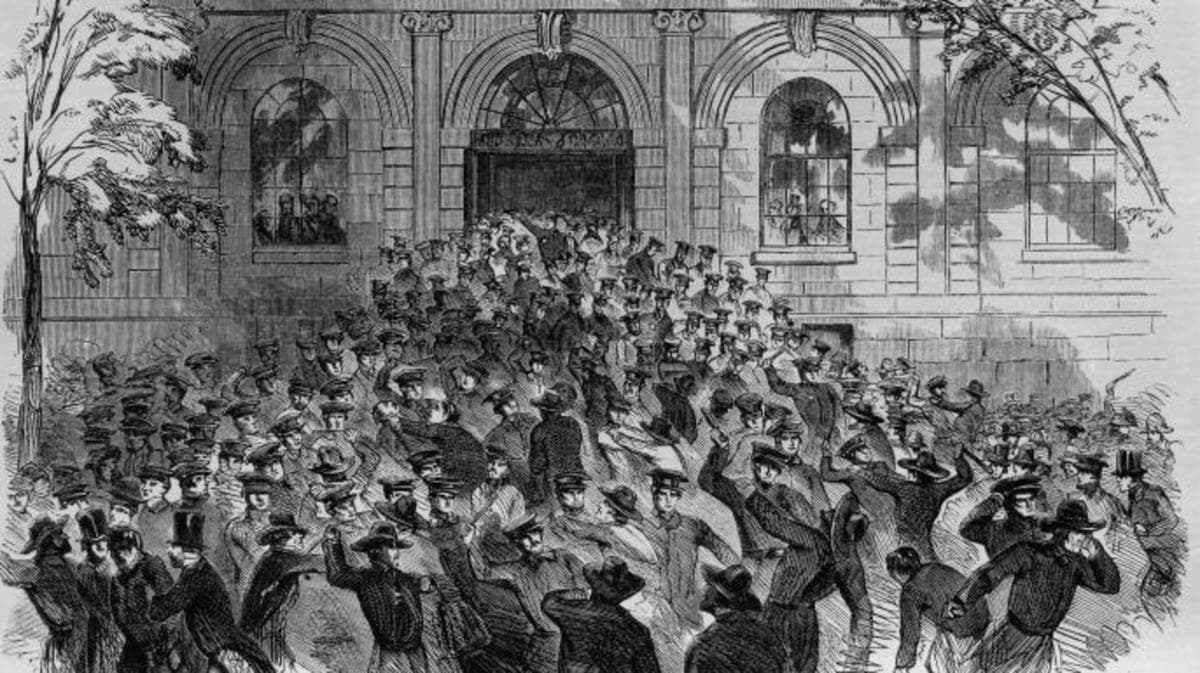

At the first performance, the audience was restless during various portions of the opera. By the second performance, restlessness had evolved into outright disturbances.

The aristocratic Jockey Club was offended by the placement of the ballet in the first act; they were used to it being in the second act so that they could finish eating dinner and arrive late without missing the dancing. (To be clear, by “missing the dancing”, we mean “missing ogling the women dancers.”)

Wagner compounded the problem by refusing to pay the claque. In France, claques were groups of audience members whose reactions could be bought and used to shape public perception of production, a bit like Instagram influencers today. However, Wagner refused to give into the French claque, with disastrous results for Tannhäuser.

During the second night, the Jockey Club disturbed the performance by blowing whistles. After the same thing happened on the third night, Wagner withdrew the opera.

3. Altenberg Lieder by Alban Berg

31 March 1913 in Vienna

Alban Berg, 1920s

This concert was so unruly that it earned its own name: the Skandalkonzert (Scandal Concert).

It happened on 31 March 1913 in Vienna’s Great Hall of the storied Musikverein. The program included works by Anton Webern, Alexander Zemlinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and Alban Berg. It was scheduled to conclude with a performance of Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder, but the event was canceled before it could be played.

Two works provoked audiences’ ire: Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1 and Berg’s Five Orchestral Songs on Picture-Postcard Texts by Peter Altenberg.

The crowd was angry at Schoenberg because a few weeks earlier, he had (rudely, people thought) refused to accept applause after a performance of his Gurrelieder in protest of conservative Viennese taste.

However, the work that broke the public was Berg’s discordant Five Orchestral Songs, of which the second and third were played.

Audiences hated the works. They called in loud voices for Berg to be committed to a mental institution. This was an especially cutting criticism since the writer Peter Altenberg (who had written the texts) was in a mental institution himself at the time.

Soon, audience members began assaulting other audience members. Apparently, concert organizer Erhard Buschbeck slapped an audience member in the face (which resulted in this concert getting the secondary nickname Watschenkonzert, or Slap Concert).

4. The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring © chethamsschoolofmusic.com

29 May 1913 in Paris

In May 1913, the daring, fashionable ballet company Ballets Russes mounted their production of The Rite of Spring.

The Rite of Spring was meant to evoke a kind of barbarous “prehistoric” pagan Russia.

Different classes and cliques reacted to the ballet’s music and choreography in different ways, resulting in scattered disturbances in the theater’s auditorium.

Over the years, the stories about this premiere got wilder and wilder. Two years after the performance, author Carl van Vechten claimed that a fellow audience member pounded fists on his head. By the 1920s, music critics were hinting at a more extreme audience reaction than had actually occurred, and by the 1940s, commentators were using the word “riot” for the first time to describe what had happened.

In the end, this concert made this list not because of what actually happened, but because of the famous stories that came out about the night.

5. The Awakening of a City, The Meeting of Automobiles and Aeroplanes by Luigi Russolo

Luigi Russolo, ca. 1916

21 April 1914 in Milan

In 1913, avant-garde painter and Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo wrote a manifesto called The Art of Noises.

He believed that the mechanized sounds of modern urban life could revolutionize concert music, if only they could be accurately and reliably reproduced in a hall.

To help him achieve his goal, he created an orchestra of new instruments called intonarumori, or noise instruments.

These instruments replicated everything from a car engine to a spatula scraping a dish.

On 21 April 1914, the first public concert of the intonarumori was given. People were so upset with his ideas that projectiles were thrown onto the stage even before the curtain opened (Russolo believed that they were students egged on by officials at the Milan Conservatory).

Once the instruments began playing, some of the instrument operators went to physically assault audience members. Apparently, the fights lasted for half an hour, and Russolo continued conducting the ensemble throughout the whole thing.

6. George Antheil Premieres

Berenice Abbott: George Antheil, 1927

4 October 1923 in Paris

American composer George Antheil was known as a bad boy of classical music, unafraid to alienate audiences with his vision of music of the future.

Like many artistic Americans in the 1920s, Antheil moved to Paris and rented an apartment above the famous Shakespeare and Co. bookstore, known as a hub for leading art figures. From there, he got to know and befriend many of the movers and shakers of 1920s Paris.

In 1923, he was asked to make his debut at a performance of the Ballets suédois (Swedish Ballet) in Paris. He performed a handful of works, including his Mechanism, Airplane Sonata, and Sonata Sauvage.

Apparently the audience wasn’t prepared for such abrasive music. To Antheil’s delight, a hubbub developed.

He described it later: “People were fighting in the aisles, yelling, clapping, hooting! Pandemonium! … the police entered, and any number of surrealists, society personages, and people of all descriptions were arrested.” He noted with satisfaction that “Paris hadn’t had such a good time since the premiere of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps.”

A variety of creative celebrities were present, including Picasso, Cocteau, Milhaud, and Satie (who apparently was heard yelling, “What precision! What precision!”).

The Inhuman Woman 1924

Adding another layer to the fracas is the fact that the riot was staged, as filmmaker Marcel L’Herbier was filming the crowd for his film L’Inhumaine, which required footage of an unruly crowd (starting at around 59:30 in the video above).

7. Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny by Kurt Weill

Kurt Weill

9 March 1930 in Leipzig

In Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s musical theater work Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, a truck transporting three fugitive criminals breaks down out of the range of law enforcement.

The three criminals decide to found a city and devote it to fulfilling human desires of all kinds: desires for pleasures like money, good food, alcohol, and sex.

People can’t make enough money to sustain themselves in Mahagonny, and deflation eventually hits the city. The government shifts from an anything-goes attitude to prohibiting certain behaviors.

After a hurricane that everyone feared would destroy the city misses Mahagonny, the rules revert back to “anything goes”, demonstrating how the city’s morals change on a dime according to the whims of those in power.

In the hubbub, a citizen named Jimmy Mahoney bets all of his money on a prizefight and loses. He cannot pay his bills and is prosecuted and killed by the state for not having enough money.

The satire’s seemingly anti-capitalist message, combined with Brecht’s sympathy for communist thought, combined to make Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny a controversial work.

Nazi sympathizers were especially unhappy. Austrian critic Alfred Polgar described the night of the premiere: “Belligerent shouts, hand-to-hand fighting in some places, hissing, applauding… enthusiastic fury mixed with furious enthusiasm.”

When the work came to Frankfurt, 150 Nazi sympathizers stormed the auditorium and set off fireworks. A Communist sympathizer was killed later that night.

Shortly after the Berlin run of the opera came to a close, the Nazis gained power in the Reichstag elections, paving the way for Hitler. Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny was banned by the Nazis in 1933.