David Gutman

Thursday, April 17, 2025

Prokofiev’s most popular concerto has inspired a range of interpretations since the composer’s own 1932 recording. David Gutman picks the finest from a burgeoning discography

Sviatoslav Richter, a great admirer of Prokofiev’s work who considered its creator positively dangerous, left us with a vignette of the man at his worst. ‘One day a pupil was playing him his Third Concerto, accompanied by his teacher at a second piano, when the composer suddenly got up and grabbed the teacher by the neck, shouting: “Idiot! You don’t even know how to play, get out of the room!” To a teacher! He was violent. Completely different from Shostakovich, who was forever mumbling “Sorry”.’ Richter, who played Prokofiev’s Fifth Piano Concerto under the composer’s direction at his last Moscow concert in March 1941, avoided the Third, a piece more readily accepted on both sides of the Iron Curtain than almost anything else he wrote. Its discography has grown exponentially since the 1950s but is not without its own black holes and unanswered questions. Prokofiev may have contributed more new music to the standard repertoire than Schoenberg and Stravinsky but his motivation remains a puzzle. The brute who delighted to offend was also a traditionalist in search of a good tune who rarely strayed beyond hand-me-down classical forms. Like Beethoven he completed five concertos for his own instrument, losing interest once he no longer had to play for a living yet continuing to produce sonatas.

By now a peripheral member of the Diaghilev set, Prokofiev spent the summer of 1921 on the French Channel coast in upbeat mood assembling a calling card for his idiosyncratic pianistic brand. The juxtaposition of material from long ago (the sharp-witted subject of the Concerto’s second movement dates from 1913) with later ideas, including some intended for an aborted ‘white-key’ string quartet, reinforced that familiar fondness for ‘stepping on the throat of his own song’. Literally international – Prokofiev was entering his fourth year of peripatetic semi-exile – the music has remained fresh for more than a century, its balancing act between the lyrical and the circus constantly renegotiated. On a purely technical level, pianists have become increasingly adept at the acrobatics, orchestras ever more meticulous in support.

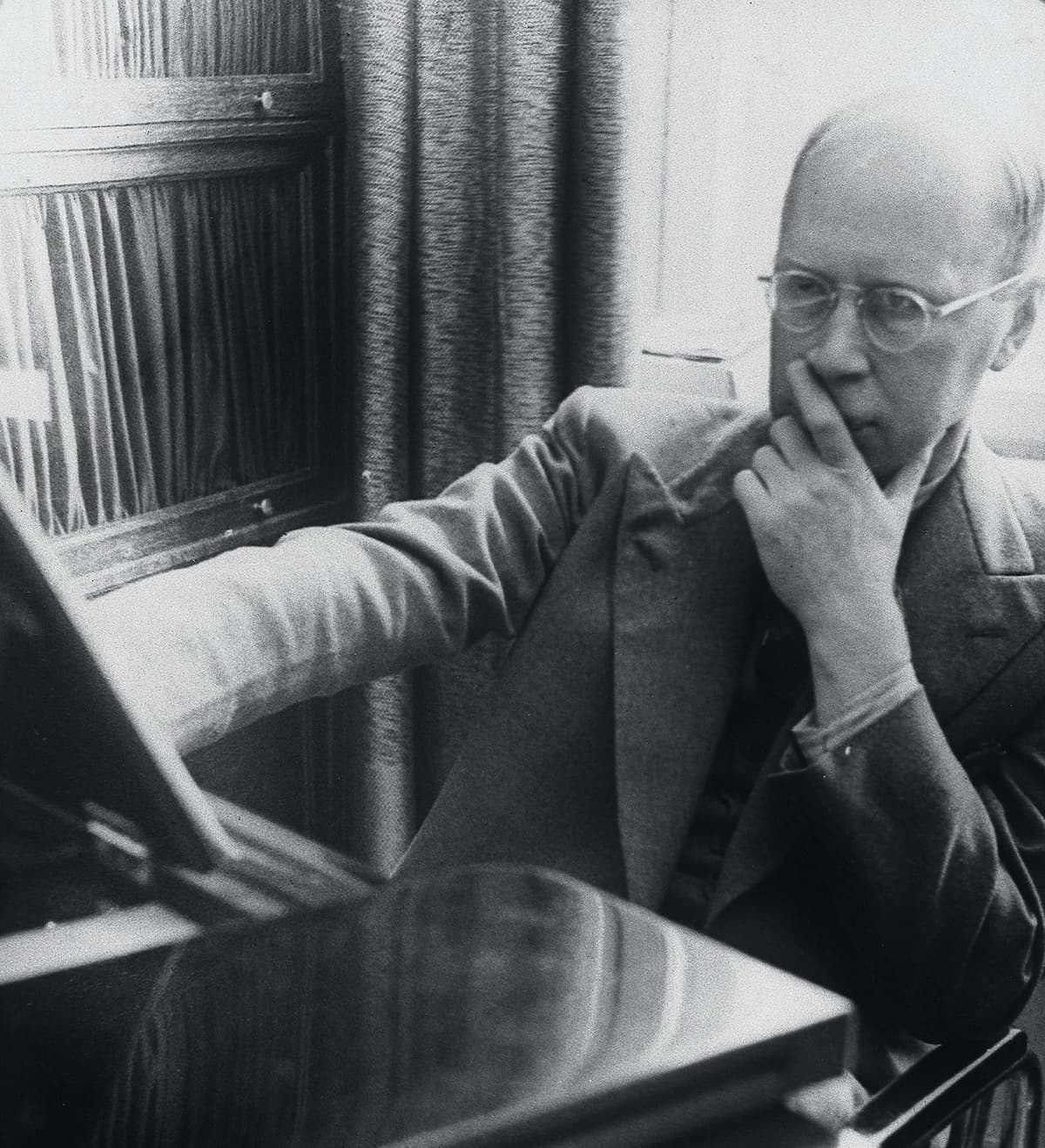

Sergey Prokofiev completed his Third Piano Concerto – the most popular of his five – in France in 1921 (Tully Potter Collection)

There are the usual three movements in which the solo part fairly bristles with innovation. That said, the story begins in a nostalgic dreamworld which performers either interpret as a temporary distraction or indulge with a heavier hand. Apart from its lissom clarinet theme, the Andante – Allegro’s material consists of a first group of aerobic exercises, a contrasting wrong-note gavotte and an aggressive tarantella-like passage which unexpectedly pitches us back into a full-throated recall of the opening.

The second movement is a theme and variations, launched in Prokofiev’s ‘neoclassical’ vein, the theme titivated by precisely notated, frequently ignored slurs, dots and accents. How far the variations should stray from the theme is moot. There are five plus a return to the main idea, gently guyed by the pianist’s clipped staccato chords, before a coda. It may have been a mistake to mark the first variation L’istesso tempo. Some pianists ignore the injunction altogether, anxious to avoid the impression that we are listening to a reiteration rather than a makeover. Most of the variations offer what were once insuperable and inspiring technical challenges – Oscar Levant reports that George Gershwin kept the score close by him. If the soloist is so minded, Prokofiev’s fourth variation locates a deep space of nocturnal stasis. The movement’s plagal cadences and mainly instrumental appendix can either be brushed aside or suggest a longing for home implied by the Molto meno mosso and espressivo markings.

The finale mixes extrovert display with a degree of emotional uncertainty. Its slower central section gives us a ‘big tune’ even if, as in the Second Piano Concerto, all may not be quite what it seems. Some performers give the theme the full-on Hollywood treatment, others highlight the pianist’s querulousness as endorsed by muted violins and squawking woodwind. The last pages encode a famously gymnastic sprint to the finishing line, one designed at least in part for its dazzling visual impact. Those who shy away from audiovisual recordings of non-operatic music will miss out on some distinctive readings showcasing the younger generation.

Having given the Concerto its premiere on December 16, 1921, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Frederick Stock, Prokofiev performed the piece on numerous occasions, first in New York, later in Paris and London. Not everyone enthused. The Musical Times wrote off the existing concertos in no uncertain terms: ‘None but the composer has yet been known to play one [sic]. In a way it is infantile. You think of a singularly ugly baby solemnly shaking a rattle. But no; it is not so human as that …’

The earliest recordings

A pity that such distinguished past collaborators as Serge Koussevitzky, Albert Coates, Henry Wood and Eugene Goossens were passed over when HMV set down Sergey Prokofiev’s ‘definitive’ interpretation of the work at Abbey Road in 1932. The task of holding things together went to Milan-born Debussy specialist Piero Coppola, the artistic director of the company’s French branch, supposedly instrumental in luring the composer into the recording studio for the first time. Be that as it may, the composer’s diaries confirm that he was uncomfortable with the process and, although the recording gives us a good idea of his distinctive timbre and insistent rhythmic drive, it may disappoint today. Presumably unwilling to compromise on tempo, Prokofiev often races ahead. And with no consistent pulse established for the main body of the first movement, its first group is recapitulated at an unrelated (faster) speed. In the second movement transitions between variations are fraught. Prokofiev simplifies the dynamics at the arrival of Var 2, rushes Var 3’s syncopated deconstruction of the theme and fails to agree an exit strategy from Var 5. He tends to operate continuously at one dynamic level before hopping to another. For sceptical listeners the Concerto is in danger of turning into a frantic cartoon, a caricature of itself.

On his first return visit to Russia in 1927 Prokofiev performed the Concerto with the ideologically inspired conductorless orchestra Persimfans, initiating an unlikely sub-category of renditions without conductor in the West. Barring exhaustive rehearsal the dangers could only multiply, despite which the work’s second commercial recording was made under just such conditions by Dimitri Mitropoulos with Philadelphia Orchestra players during their off-season summer series. Certain passages muddled by Prokofiev and Coppola go well; much is scrappier. Mitropoulos, as undisciplined at the keyboard as he sometimes was on the podium, slams on the brakes at the very end of the finale. While he is not alone in this, it makes no sense. Van Cliburn, who made his official studio recording in Chicago (RCA, 8/61), risks fewer deviations directing from the keyboard in a lo‑fi Soviet-era telecast. The trumpets get lost entirely in the theme and variations but the band’s timbral specificity, the pianist’s straightforward manner and his full tone offer their own rewards. In recent tours Lahav Shani and the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra have included such renderings with results as clean and polished as any. No commercial audio recording, though.

Arriving at the tail end of the 78rpm era, William Kapell’s 1949 account is a significant marker, outpacing even Prokofiev’s ‘fingers of steel’. Antal Dorati’s Dallas Symphony Orchestra prove fallible, unable to manage the transition from Var 5 to the return of the main theme, but Kapell’s blistering technique heralds an era in which an ill-starred generation of American pianists would remake the Concerto as a vehicle for their own prodigious talents. Kapell himself died in a plane crash aged 31, Julius Katchen was taken by cancer aged 42, while Byron Janis and Gary Graffman suffered incapacitating problems with their hands; Cliburn merely suffered burn-out. The first American to tour Russia on a cultural exchange, Janis’s subsequent recording was the first to be made there using Western equipment and technical staff imported for the occasion. Having Kirill Kondrashin’s expert Moscow Philharmonic in support adds character without the poster-paint crudity commonly associated with Soviet orchestras. Without the benefit of close-up Mercury stereo on 35mm film, Kondrashin had previously collaborated with the great Emil Gilels on a mono LP barely distributed in the West. Home-pressed releases from the likes of Samson François (Columbia, 3/54) and Leonard Pennario (Capitol, 11/54) also failed to last long in the catalogue. Moura Lympany (HMV, 9/57) is in early stereo but hampered by Walter Susskind’s stodgy treatment of the second-movement theme. A few years later, on the other side of the pond, Gary Graffman would have the support of George Szell’s Cleveland Orchestra in prioritising clangorous rigour over intimacy and humour. Katchen’s remake with the LSO and István Kertész (Decca, 5/70) arrived posthumously, by which time a rather different approach to the Concerto was making waves.

Into the modern era

In 1967 we arrive at one of Martha Argerich’s most celebrated recordings, and it is here that the modern performance history of the Concerto really takes off. After so much unyielding tone she brings unprecedented light and shade to the work, proving that it can be lyrical and whimsical as well as barnstorming. Gramophone’s critic, who should perhaps remain nameless, made reference to ‘abundant signs of femininity in wonderfully delicate, clear passagework and the most elegant phrasing’. The Karajan-era Berliners adapt well to Claudio Abbado’s feline proclivities; Argerich’s steadier Montreal version with Charles Dutoit (EMI, 10/98) feels weightier. There have since been many more remakes, official and unofficial given the pianist’s permissive attitude to sharing music online. BBC footage from 1977 in which Argerich is the guest of André Previn’s LSO popped up on DVD in 2012 and remains accessible via video streaming platforms. Sound may not be top-notch but old-school mise en scène focuses on her hands to spellbinding effect: there’s no cheating towards the end!

Vladimir Ashkenazy’s 1974 account with André Previn still holds firm (Photography: Suzie Maeder - Bridgeman Images)

By now the first cycle of all five concertos was under way in Boston, though neither John Browning nor Erich Leinsdorf sound much engaged by the Third, which they had previously taped in London (Capitol, 3/62). As so often the main theme of the second movement is smoothed over. Also unstylish though more boisterous are Alexis Weissenberg and Seiji Ozawa in Paris (HMV, 9/71). Moving forwards to perhaps the most durable of the complete sets, Vladimir Ashkenazy and the LSO under Previn elicit an emotional variety missing elsewhere. Dry, close-miked castanets in the first movement feel like a throwback to 1932. Elsewhere the approach is Russian and/or Romantic, as in the very free treatment of the second movement’s Var 1. Ashkenazy is no shrinking violet, the opening of his third movement notably impactful. Jon Kimura Parker, also with Previn (Telarc, 12/86), offers similar solutions in less dramatic, perhaps less ego-driven fashion. The same might be said of Michel Béroff with Kurt Masur, whose Leipzig musicians sound timbrally distinct from their West European counterparts in another first-rate 1970s cycle.

Rediscovered: a poised Maurizio Pollini (Interfoto - Alamy Stock Photo)

Those who find Argerich too flippant shouldn’t look to Maurizio Pollini to restore the machine-age thrust of Italian futurism, his take on the score being essentially poised and aristocratic. A studio recording released during the years when he was playing the Concerto in public (qv Turin footage online) might have changed the way we hear it now. As it is, the belated release of a Tokyo broadcast allows us to savour his wonderfully pure, crystalline tone. There is surely no pianist one would rather hear play a long trill followed by a glissando-like run up the keyboard. Ivo Pogorelich is the one major advocate whose interpretation remains officially unavailable. His spacious, ultra-sensitive way with Var 4 is very special.

Another outlier in compromised sound is Terence Judd, taped at the 1978 Moscow Tchaikovsky Competition, in which the British pianist came joint fourth. Ecstatic drive tempers steeliness in this prime souvenir of a star whose career was cruelly cut short aged 22. The competition was won by Mikhail Pletnev, whose own later studio recording seems cold (DG, 6/03). Glenn Gould once cited Prokofiev’s ability to achieve ‘maximum effect for minimum effort’. That comment doesn’t make much sense until you hear Pletnev using his transcendental gifts to coast. Nikolai Lugansky is another Russian whose lucidity and control compensate for an adrenalin deficit (Naïve Ambroisie, 1/14).

The Concerto comes home

Most all-Russian recordings adopt a heavier style, sometimes attributable to the broader ideological priorities of music-making in the Soviet era and beyond. Viktoria Postnikova’s 1985 cycle with Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s USSR Ministry of Culture Symphony Orchestra (Melodiya, 9/96) unfolds as if determined to subvert reductive gender stereotypes. Vladimir Krainev’s first recording (HMV Melodiya, 9/79), a cult classic, is currently more elusive than his Frankfurt-made remake, part of a second complete set again under Dmitry Kitaenko. Unforced errors aside, Krainev rather brutalises his very first entry, playing its final note fortissimo rather than letting the line recede into the orchestral texture as implied by the mezzo-piano marking. Treating the end of the first movement more precipitately than anyone else until Daniil Trifonov, Krainev goes to the other extreme in the next with his other-worldly take on Var 4. Alexander Toradze is more consistently pugnacious in his Mariinsky cycle with Valery Gergiev, Denis Matsuev ultimately exhausting in a hard-driven one-off issue with the same forces (Mariinsky, 4/14).

Mixed casting continued to attract the record companies. Cécile Ousset (EMI, 12/83), another really big player but no speed merchant, is paired with Rudolf Barshai in Bournemouth. Soviet-born Israeli-American Yefim Bronfman recorded his accomplished cycle with Zubin Mehta and the Israel Philharmonic, lacking only the last ounce of personality to set it apart. Moscow-born at least, Yevgeny Kissin joined Claudio Abbado’s gilt-edged Berliners for the second and best recorded of his three versions. Kissin is masterly, the orchestral response oddly pale as could be the case with Abbado in this period. Then again, the pianist himself offers few magical half-lights in Var 4 and refuses to rush the end of the finale.

The 1990s brought a bargain-basement series from Kun-Woo Paik (Naxos, 11/92) and a fancier one from Nikolai Demidenko with Lazarev and the London Philharmonic (Hyperion, 11/96). Acclaimed in the 2010s was a Gramophone Award-winning set from Jean‑Efflam Bavouzet in which, as Rob Cowan noted, the pianist displays a chameleon-like response to the disparate personalities of each piece rather than imposing his own template across the board. The Third becomes a slightly low-key neoclassical entity, its first movement almost dapper, the second notable for the super-attentive contribution of Gianandrea Noseda’s BBC Philharmonic. There’s a degree of motoric abstraction in music that need not be sugar-coated. A similarly sophisticated orchestral backdrop is a feature of Simon Trpčeski’s rendition with Vasily Petrenko’s RLPO (Onyx, 8/17). Andrew Litton provides warmer but finely detailed support for Freddy Kempf and Stewart Goodyear. Both enjoy top-notch sound engineering beside which older favourites risk coming across as dated.

Prokofiev’s secco writing suits Olli Mustonen (Heikki Tuuli)

A keen individualism informs the work of four 21st-century mavericks, the first two being Graffman pupils. Yuja Wang, closer to Argerich in style, has a natural empathy for Prokofiev. Caught early in her career in a relay from the 2009 Lucerne Festival, she dazzles – of course – while admitting a certain whimsicality in a reading that never runs counter to Abbado’s re-engaged, essentially anti-Romantic conception. Is that why the audience response, like the balance accorded her instrument, is curiously muted? Lang Lang opts for a broader canvas that some might find unnecessary although there is certainly a case for it. Memorable is the free cadenza-like treatment of Var 1. Less happily, the finale’s big tune goes way over the top, with Simon Rattle’s Berliners rather gloopily sentimental in support. Daniil Trifonov takes us back to Russia with a brilliant, radically intense account filmed as part of Gergiev’s Prokofiev binge of 2016. These 125th anniversary celebrations had the imprimatur of Putin himself and the orchestral playing is perhaps statelier than the music warrants. Or is the upscale treatment all Trifonov’s idea? He imparts the shock of the new regardless of tempo, perennially open to original voicings. Particularly extraordinary is the middle section of the finale, where un-Lang Lang-like anxiety never wholly dissipates.

Olli Mustonen pushes still further into unknown territory, remorselessly crisp and non-legato with an aversion to the sustaining pedal. It’s as if fresh characters have invaded a familiar narrative, stalking the text in a language we can’t quite read. Many will reject the experiment although, being paradoxically gentler than usual, the results bring us closer to the ‘fairy-tale’ Prokofiev of the First Violin Concerto.

These disparate readings confirm that in what remains Prokofiev’s most popular piano concerto the story need not end with Martha Argerich, unparalleled though her engagement with the score has been. Our survey does so, but then you were expecting that all along!