It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Showing posts with label Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Show all posts

Sunday, August 24, 2025

Friday, August 15, 2025

10 Greatest Piano Concerto Openings of All Time

by Emily E. Hogstad

There’s something thrilling about the opening of a great piano concerto. The big instrument gets rolled onstage; the soloist and conductor stride out to applause; the pianist sits and raises their arms and nods to the conductor to begin.

Today, we’re looking at piano concerto openings that have a claim to be among the best: excerpts that are particularly striking, surprising, or spellbinding.

Of course, when it comes to ranking classical music, there is no such thing as an objective list. Today, we’ve made some subjective calls and made a countdown list in reverse order.

Keep scrolling to find out which piano concertos we think have the best openings, and which concerto nabbed the number one spot.

10. Robert Schumann: Piano Concerto in A minor

The first movement of Robert Schumann’s piano concerto began life as a Phantasie in A minor, which he wrote over the course of four days in May 1841.

He had just married Clara Wieck, one of the great pianists of her generation, and the work was clearly inspired by her.

Robert and Clara Schumann

Clara was so taken by the Phantasie that she urged him to write two more movements to make it an official piano concerto. He did so in 1845, and she premiered the whole concerto in December 1845.

The concerto begins with a bold, unsettled statement by the soloist, followed by a sympathetic response by the orchestra.

The soloist answers the orchestra in a dreamy way, but she soon begins to brood. And with that, listeners are off to the races.

9. Saint-Saëns: Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor

This concerto dates from 1868, the height of the Romantic Era, so you might expect it to begin with a lush, Romantic flourish.

Instead, Saint-Saëns begins with a jaw-dropping solo cadenza that is clearly a tribute to Baroque Era master Johann Sebastian Bach.

This unexpected homage makes for one of the most arresting openings in the entire piano repertoire.

After the soloist pounds out the gutsy tribute to Bach, the orchestra steps in with a dramatic, almost operatic response. The piano replies, beginning a dialogue between the two forces.

The work does eventually ease into a more Romantic language, but it does so while retaining a kind of aloof Baroque aesthetic…making for a fascinating tension.

8. Gershwin: Rhapsody in Blue

We’re cheating a little bit by including this one, since, technically speaking, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue isn’t a concerto. However, its opening is so iconic that it had to go on this list.

Why? That opening clarinet glissando. (In fact, that entire opening clarinet solo is unforgettable.)

Amazingly, this iconic moment in music history came about by accident.

Portrait of George Gershwin

Charles Schwartz writes in his 1979 biography:

As a joke on Gershwin…[Ross] Gorman [the clarinettist at the premiere] played the opening measure with a noticeable glissando, “stretching” the notes out and adding what he considered a jazzy, humorous touch to the passage. Reacting favorably to Gorman’s whimsy, Gershwin asked him to perform the opening measure that way…and to add as much of a “wail” as possible.

This delightful accident set the stage for a work that melded the long-standing traditions of European art music with the fresh energy of American jazz.

7. Mozart: Piano Concerto No. 20 in D-minor

Mozart wrote 27 piano concertos. Only two were written in a minor key. This was the first.

This music here sounds theatrical: like the overture to an opera set on a windswept island.

As per Classical Era convention, the soloist doesn’t enter until over two minutes in. The solo part calls for a pianist to meld restraint with storminess.

6. Liszt: Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major

Franz Liszt began writing his first piano concerto in 1830, when he was 19. According to scholars, its main themes date from this time. However, he didn’t finish and premiere it until 1855.

The opening features a bold, sassy statement in the orchestra, followed by a mind-boggling display of virtuosity by a snarling solo pianist.

Legend has it that Liszt assigned sarcastic lyrics to this opening theme: Das versteht ihr alle nicht, haha! (“None of you understand this, haha!”).

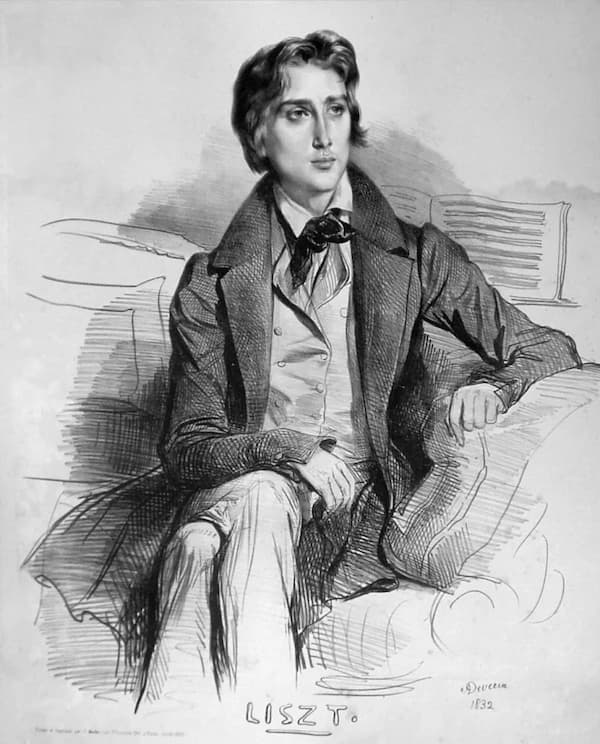

Franz Liszt

This opening theme recurs throughout the work. It’s no wonder that Béla Bartók called the concerto “the first perfect realisation of cyclic sonata form.”

5. Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 1 in D-minor

The opening to Brahms’s first piano concerto has a shocking gravity to it, especially for a composer in his early twenties.

But despite his youth, Johannes Brahms had already been through a lot. One of his mentors, Robert Schumann, had recently attempted suicide by jumping into the Rhine. After he was rescued, Schumann agreed to move into an institution for his and his family’s safety.

Many people believe that the falling sensation depicted in the opening to this concerto is a reference to Schumann’s plunge into the water and the depths of incurable mental illness.

As if all that weren’t enough, Brahms was also falling in love with Robert’s wife, Clara, who was pregnant with her eighth child, and fourteen years Brahms’s senior. The two would never marry, but would be close soulmates and creative partners for decades to come.

The tragedy and trauma of witnessing Robert’s illness, Clara’s devastation, and his own doomed love are immediately obvious in this concerto’s opening moments.

4. Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G-major

On its own, this unassuming opening might not seem particularly striking.

But here’s some important context: at the time of this concerto’s composition in 1805-1806, it was not standard for a soloist to begin a concerto.

Beethoven‘s crafting of an opening to a concerto where the orchestra didn’t state the theme first was revolutionary.

Breaking this rule encouraged later composers to create several of the other great concerto openings on this list.

3. Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor

This concerto begins with a short but monumental French horn call.

Next, the soloist accompanies a lush, wistful string theme with massive chords. The instrument practically plays a percussive role here.

Finally, the soloist takes the spotlight in a commanding solo cadenza, creating an intimidating aura of grandeur.

2. Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 2 in C-minor

Countless classical music lovers have been drawn into the art by the dark, hypnotic opening of Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto.

The opening chords in the solo part peal out like bells and lead to an equally dark, lush theme in the strings.

In under sixty seconds, Rachmaninoff creates a swirling world of passion and heartbreak.

Even today, this opening remains one of the most cinematic moments in the entire piano repertoire. (And, in fact, this concerto has been used in a number of classic films over the decades.)

But in the end, there can only be one greatest piano concerto opening of all time, and today, on this very subjective list, the prize is going to:

1. Grieg: Piano Concerto in A-minor

Everything about this opening is unforgettable:

- The menacing, thunderous timpani roll.

- The heroic cascade of chords from the soloist, equal parts tragic and terrifying.

- The orchestra coming in with an unforgettable, folk-inspired melody.

It’s the perfect opening to a piano concerto.

Interestingly, Grieg was inspired by the first concerto on this list: Robert Schumann’s. Notably, it’s in the same key and features similar gestures in the opening…bringing this list full-circle!

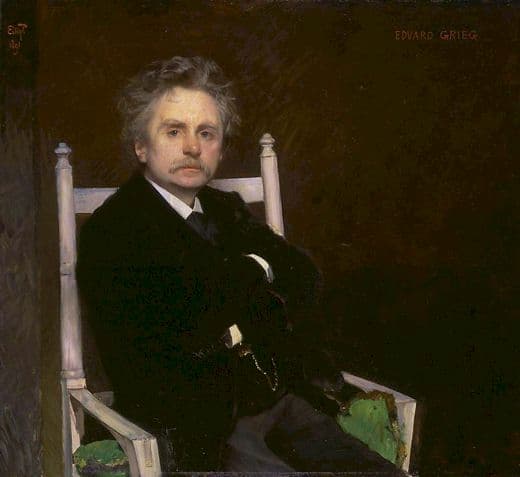

Edvard Grieg, 1891

What’s your favourite piano concerto opening?

Friday, June 6, 2025

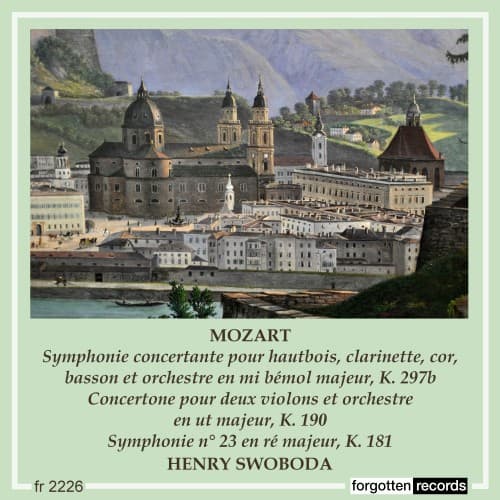

Lost and Recreated: Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, K. 287b

by Maureen Buja

In February 1778, Leopold Mozart told his son to go to Paris with his mother, and the pair arrived in the capital city in March 1778. He immediately started to set up his musical networks and wrote to his father about his activities: he was writing music for choruses for a Miserere by Holzbauer and wrote a Sinfonia Concertante for an ensemble of flute, oboe, bassoon, and horn. However, no such work has even been found.

Croce: Mozart Family Portait (detail), 1781

The sinfonia concertante has a very limited life. It was a successor to the Baroque Concerto Grosso but written for a group of soloists and orchestra. Each soloist has its own prominent role, but at the same time, each soloist is part of the orchestral ensemble. It fell out of use as a genre in the Romantic era but was taken up again in the 20th century by composers such as George Enescu and William Walton.

What we know now as the Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major (K. 297b) is scored for oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn. Is this the same work Mozart was referring to in his letter to his father, or something that was just slipped into Mozart’s catalogue because it seemed to fit the bill?

The work came into the repertoire in 1869, and it took nearly a century for it to be questioned. The Sinfonia Concertante in E flat major was considered to be fully by Mozart until 1964, when the editors of the New Mozart Edition decided to banish it to the list of ‘dubious and spurious works’. This is not uncommon, particularly with famous composers such as Mozart – many later composers were more than happy to have their works circulating (and earning royalties) under another’s more famous name. The number of spurious works by Pergolesi is astonishing in its breadth, for example.

Without a manuscript in Mozart’s hand, the question of whose work this might be broadens considerably. Scholars in the 1960s wondered if, perhaps, the solo work was Mozart’s, and the orchestra accompaniment might be by another hand.

The only known source for the work was a copyist’s manuscript from the mid-19th century. When scholars started looking more closely at the piece, however, some problems quickly emerged. When the instrumental writing of the Sinfonia Concertante was compared to known Mozart works, the solo instruments had anomalous disparities from the norm in terms of range (tessitura). The orchestral accompaniment is more like writing from the early 19th century rather than the mid-18th century. The only known source (the copyist’s manuscript ) was prepared for the Mozart biographer Otto Jahn by one of his copyists and doesn’t have any composer’s name on it – the theory is that Jahn’s copyist had a set of the solo parts (flute, oboe, bassoon, and horn) and made his reconstruction updating the instrumentation (oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn) and added the missing orchestral accompaniment.

It is thought that Mozart’s original score was written for four instrumentalists, 3 from Mannheim, who were in Paris when Mozart was there: flautist Johann Wendling, oboist Friedrich Ramm, and bassoonist Georg Ritter from Mannheim, plus the horn player Johann Stich (known as Giovanni Punto). However, there was no Paris performance, and the score vanished. Mozart suspected local intrigue was involved in silencing his work. The work was commissioned by Joseph Legros for performance at his Concerts Spirituels series. However, the composer Giuseppe Cambini interfered, and the performance never occurred. Although not well-known today, Cambini was extremely active in Paris from the early 1770s – by 1800, some 600 instrumental works had been published under his name, and he had symphonies concertantes performed at the Concert Spirituel starting in 1773.

What has intrigued scholars and performers alike is the fact that the work doesn’t show Mozart at his best, but has enough of a ‘whiff’ of Mozart about it to indicate that he may have been involved somehow with the surviving copyist’s score. The problem, of course, is that this is the only work like that that Mozart wrote, and the difficulty of setting up a definition of ‘normal’ on a unique work is almost insurmountable.

Authenticity aside, performers welcomed a ‘new’ work by Mozart and the work has found a ready audience in the modern age.

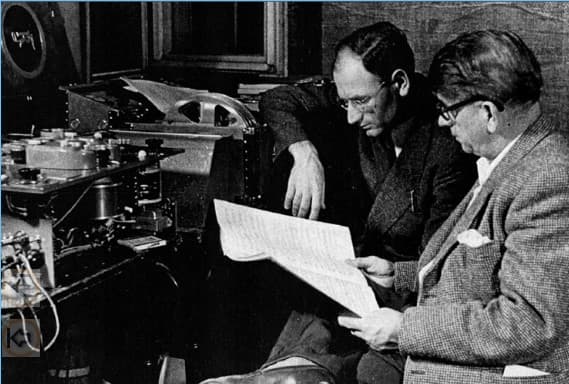

Henry Swoboda at Westminster Records with the pianist and producer Karl Welleitner

This recording was made in January 1950 by an ensemble of soloists from the Vienna Philharmonic and the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera, conducted by Henry Swoboda. Czech conductor Swoboda (1897–1990) studied in Prague and was conductor of the Prague Opera (1921–1923) and the Düsseldorf Opera before emigrating to the US in 1939. In New York, he was the music director for two recording companies (Concert Hall and Westminster) and also led the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra (1962–1964) before returning to Europe to live in Switzerland.

Performed by

Henry Swoboda

The Vienna Philharmonic and the orchestra of the Vienna State Opera

Recorded in 1950

Official Website

Saturday, January 18, 2025

Heavenly Soundscapes: The Church Sonatas of Mozart

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Mozart‘s birth was nothing short of miraculous, a moment that would go on to change the world of music forever. Born on 27 January 1756 in the heart of Salzburg, Austria, he arrived into a family already steeped in musical tradition. His father, Leopold, a composer and violinist, immediately recognised his son’s prodigious talent, and before long, young Wolfgang Amadeus was dazzling everyone around him with his unparalleled musical genius. From the very start, it was clear that Mozart wasn’t just a child prodigy; he was a once-in-a-lifetime musical force destined to push the boundaries of classical music to new heights.

Portrait of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart at the age of 13 in Verona, 1770

As we celebrate Mozart’s birthday on 27 January, we decided to showcase masterpieces of a very special kind. And I am talking about his church sonatas, sometimes also known as the “Epistle Sonatas.” Mozart wrote 17 of these short works, musical gems of concentration on the small form. As the composer himself said, “you need a special kind of training for this kind of composition.”

Forgotten Gems

Don’t feel bad if you are not familiar with these charming miniatures. These works were part of the religious service at the cathedral in Salzburg, written for a very specific function. Today, they no longer have that particular function in the liturgy of the Catholic mass, and they certainly have no fixed place in the concert repertoire. The church sonatas by Mozart have led a life in the shadow; it’s high time to bring them into the light!

Official Church Musician

Salzburg Cathedral

The church sonatas date from a time when Mozart served at the court in Salzburg in an official capacity for 10 years. Initially he was hired as an unsalaried “concert master “on 27 October 1769, but was officially on the payroll in this particular position from August 1772 to August 1777. He was then promoted to “cathedral and court organist,” with a salary of 450 guilders in January 1779. This position would be terminated by the famous “swift kick to the backside” in May 1781.

Archbishop Colloredo

Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo

Mozart had a famously turbulent relationship with his boss, Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo. Colloredo was in charge for much of the 1770s and early 1780s, but their dynamic was strained from the start. Mozart, known for his independent spirit and desire for creative freedom, was at odds with the archbishop, who was more interested in maintaining control and adhering to formalities. The tension escalated as Mozart resented the rigid, often patronising treatment he received, especially when Colloredo limited his opportunities to compose freely and perform outside Salzburg.

Liturgical Function

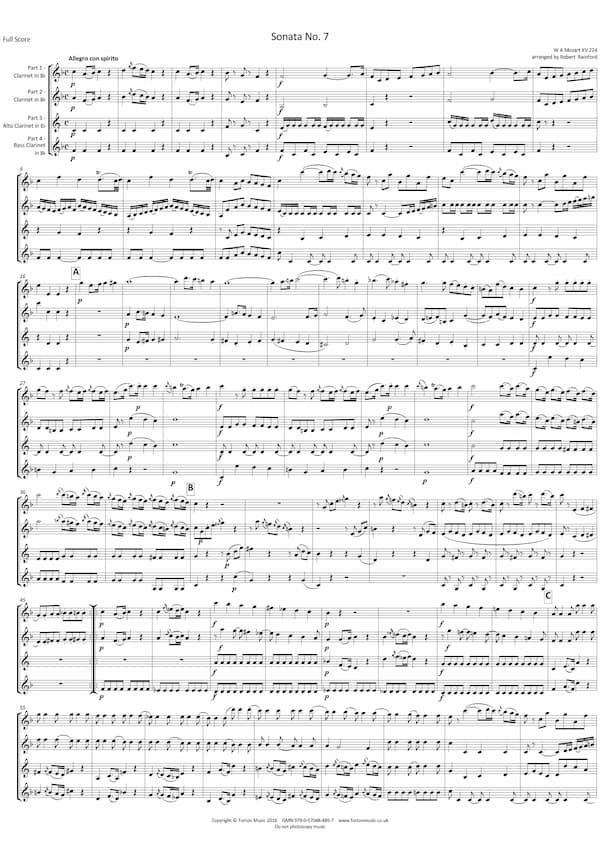

Mozart’s Church Sonata No. 7 in F Major, K. 224 music score excerpt

So, what was the specific liturgical function of Mozart’s church sonatas? We get the answer from a Mozart letter to Padre Martini from September 1776. Mozart wrote in Italian, “our church music is very different from that of Italy, since a mass with the whole Kyrie, the Gloria, the Credo, the Epistle Sonata, the Offertory or Motet, the Sanctus and the Agnus Dei, even the most solemn one, may not last more than a maximum of three-quarters of an hour when the Prince attends it; and yet it must be a mass with all instruments, war trumpets and timpani.”

Epistle Sonata

From Mozart’s letter, we learn about the position of the “Epistle Sonata” in the liturgy, but it’s still not straightforward. One scholar wrote the following explanatory footnote to Mozart’s letter. “While the priest reads the Epistle, the organist played softly a sonata with or without violin accompaniment.” We do know that this type of musical composition probably originated in northern Italian churches in the 17th century and subsequently made their way into Austria.

Solemn Occasion

I can’t believe that Archbishop Colloredo would have tolerated any kind of music to interrupt the reading of the Epistle. It is much more likely that these short instrumental works sounded between the reading of the Epistle and the Gospel as the priest solemnly walked from the southern part of the church to the Nave.

Musician Placement

Now that we know when the Epistle Sonatas would have been performed within the liturgy, we still don’t know where the musicians would have been placed inside the church. Presumably, the position would have been close to the various organs in the Salzburg Cathedral, and we are fortunate to have an exact account of the number and dispositions of the organs from Leopold Mozart.

Organs of the Cathedral

Salzburg Cathedral main organ

Leopold writes, “In the Archiepiscopal Cathedral, the large organ is placed at the back near the entrance of the church; nearer the front, at the choir, there are four auxiliary organs, and below, in the choir itself, there is a small choir-organ about with the singers are placed. During an elaborate service, the large organ is used only for playing the prelude; for the remainder of the service, however, one of the four auxiliary organs is constantly employed, particularly the one nearest the right side of the altar, where the solo singers and basses are stationed.”

Large Forces

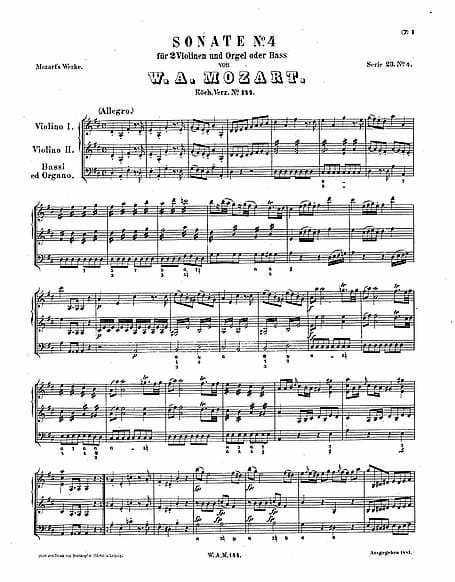

Mozart’s Church Sonata No. 4 in D Major, K. 144 music score excerpt

Leopold continues, “opposite, at the left auxiliary organ, are the violinists, etc., and the two groups of trumpets and kettledrums are near the remaining auxiliary organs. The lower choir organ and violins join in at fully scored passages. The oboes and flutes are seldom heard in the Cathedral, and the horn never. All these players are able to play violins if necessary. The full number of persons connected with music, or who receive pay for musical service at the court, is ninety-nine.”

Mozart the Organist

Since every epistle sonata features the organ in one way or another, maybe we also have to look at Mozart’s relationship with that instrument. He held an immense appreciation for the organ, and in a letter to his father in 1777, he wrote, “In my eyes and ears, the organ is the king of instruments.” However, Mozart composed virtually no works for the organ, aside from a few fugues or fragments of fugues.

Mozart the Improvisor

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart © media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com

However, when it came to playing the organ, Mozart was an undisputed master. The composer Carl Czerny reported that Mozart was able to play the organ with great virtuosity and could improvise intricate music on the spot. That impression is confirmed by Johann Friedrich Doles, Kantor of St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. After hearing Mozart improvise, he wrote, “I was enchanted by his playing and thought that my teacher, old Sebastian Bach, had been reborn.”

The 17 Church Sonatas

Mozart composed a total of 17 Church Sonatas during his tenure at Salzburg Cathedral. They correspond, as Martin Haselböck has observed, with the seventeen instrumental masses composed by Mozart. Scored predominantly for strings and organ, which function either as a solo instrument or as continuo, these works display Mozart’s genius for melody, form, and instrumentation. The first three sonatas, K. 67-69 were possibly written when Mozart was only about eleven years old.

Early Efforts

The actual date of Mozart’s earliest church sonatas is uncertain, but together with K. 144 and 145, they were probably written in the first year of Mozart’s appointment at the cathedral. As you can tell, they are really very short and probably exactly what the Archbishop wanted. As a general observation, the 17 Sonatas are written in 7 keys. Although they are all in major, Mozart does include some striking modulations into the minor key. In Mozart’s hand, as we well know, two bars of minor harmonies can say more than an entire symphony elsewhere.

Central Group

The sonatas in the group ranging from K. 212 to K. 278 originate between 1775 and 1777 and were written for the same ensemble as the first five, for two violins, cello, organ, and bass. There are only two exceptions, K. 263 added a pair of trumpets, and K. 278 featured trumpets, timpani, and a pair of oboes as it was a festive piece written for Easter Sunday in 1777.

Delicious Variety

Let us briefly look at two specific examples, first the sonata K. 244, dating from April 1776. Delicately structured and emphasising a light musical texture, this Sonata opens with a stately and invigorating yet charming musical theme. Independently contributing to the musical discourse, the organ plays a separate concertante part, clearly audible in the slightly subdued thematic contrast.

Composed in 1777, the sonata K. 274 begins with a sprightly unison passage that quickly gives way to an energetic theme. A subtle modulation gradually directs the music towards a delicate dialogue between the instruments before the opening section is repeated.

Final Efforts

The last three church sonatas, K. 328, 329, and 336, have a much more important organ part. Since Mozart would have been playing the organ, he made sure that he would have something interesting to do. K. 328 immediately displays a festive character, one that is not necessarily bound to its sacred function. Operatic in character and symphonic in its overall formal and musical structure, the independent organ part once more enriches the musical texture and provides colourful timbral contrasts.

In fact, K. 336 follows the character and convention of an instrumental concerto. Introduced in the strings, the thematic material is immediately taken over by the organ and thoroughly embellished. This miniature concerto even includes a dedicated cadenza, in which the organist performs an elaborate and virtuosic improvisation.

Stylistically, the works written during the course of one decade mirror the rapid development of Mozart the composer. While the spirit of the Italian opera pervades the early compositions, “the polyphonic structure is increasingly interrupted in favour of a symphonic development.” The great movements “correspond to the symphonic and concertante pieces written around the same time in both their construction and thematic work.”

As Gerald Larner writes, “Mozart gradually asserted his authority from K. 224 onwards, enriching both the texture and the construction, adding harmonic and colour interest, and finally achieved mastery of a peculiar Salzburg form by expanding its limitation.” I am pretty sure that Mozart managed to irritate the impatient Archbishop! While these sonatas are not as widely known as some of Mozart’s other works, they are certainly impressive in their depth and spiritual expressiveness. Happy Birthday!

Friday, December 6, 2024

The Magic of Mozart: The Viennese Piano Concertos

by Georg Predota, Interlude

The series of piano concertos Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed during his years in Vienna is undoubtedly his greatest achievement in instrumental music. The dozen piano concertos composed between February 1784 and December 1786 are works of the highest quality and originality. According to Maynard Solomon, “their artistry goes far beyond the concertos of his predecessors or his contemporaries in their scale, their thematic richness and their highly developed relationship between soloist and orchestra.”

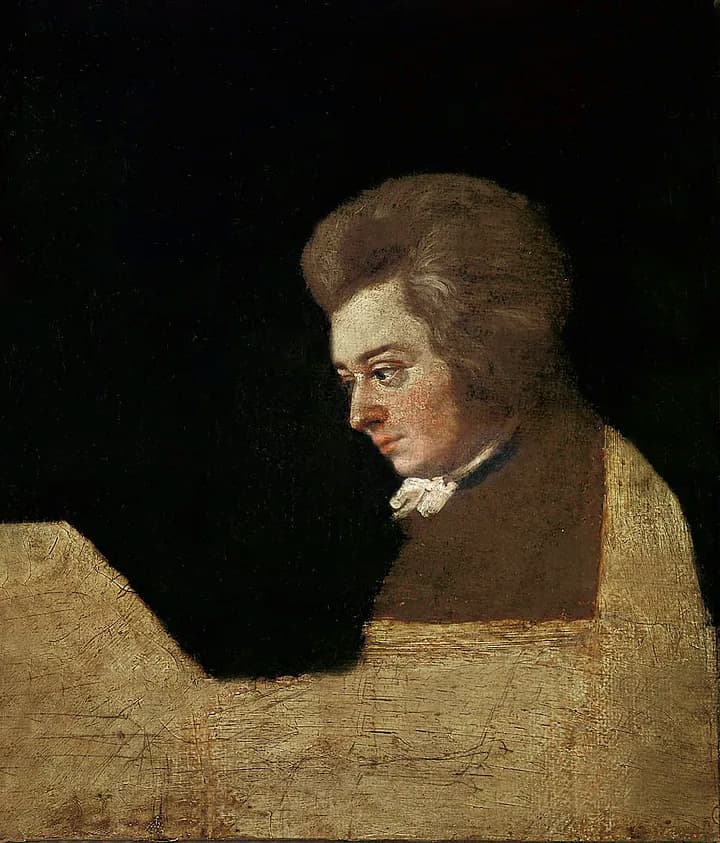

Joseph Lange: Mozart at the keyboard (unfinished), 1789 (Mozart-Museum, Mozarts Geburtshaus)

Mozart essentially created a unique conception of the piano concerto as he was looking to solve the problem of how the thematic material is to be divided between the piano and the orchestra. In these later works, Mozart “strives to maintain an ideal balance between a symphony with occasional piano solos and a virtuoso piano fantasia with orchestral accompaniment.” Mozart’s solutions are non-formulaic as each concerto, although unmistakably resembling its siblings, is a thoroughly individual response.

The Viennese piano concertos are probably the most personal works Mozart ever conceived, as they were composed for his own public performances. As we commemorate Mozart’s death on 5 December, let us explore some of these most important works of their kind.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart sent his father the list of subscribers who paid an entrance fee of six gulden for three concerts at the Trattnerhof on 20 March 1784. “Here you have the list of all my subscribers,” he writes, “I have 30 subscribers more than Richter and Fischer combined. The first concert on March 17th went off very well. The hall was full to overflowing, and the new concerto I played won extraordinary applause. Everywhere I go, I hear praises of that concerto.”

The concerto in question was Mozart’s K. 449, and Mozart had gotten involved in subscription concerts via his colleague Franz Xaver Richter. Richter had rented a hall for six Saturday concerts, and the nobility subscribed. However, as Mozart writes, “they really did not want to attend unless I played. So Richter asked me to play. I promised him to play three times and then arranged three subscription concerts for myself, to which they all subscribed.”

Mozart suggested that K. 449 “is one of a quite peculiar kind,” and he called it a happy medium between what is too easy and too difficult. In fact, K. 499 is rather intimate chamber music with the “Allegro Vivace” exploring the tensions between the major and minor tonalities. An exquisitely expressive “Andantino” gives way to a dazzling rondo featuring much contrapuntal wizardry.

The Piano Concerto No. 17, K. 453 is one of only two by Mozart to have been written for a player other than himself. In fact, it was written for his student Barbara Ployer, daughter of Gottfried Ignaz von Ployer, a Viennese emissary to the Salzburg court. Ployer was a fine pianist and she soon became one of Mozart’s favourite students. He also provided her with counterpoint instructions, and he asked her to come up with musical ideas of her own. Leopold Mozart was not impressed and wrote, “You want her to have ideas of her own—do you think everyone has your genius?”

Mozart monument in Vienna

The orchestration of this concerto is notable for the independence Mozart provided to the woodwinds. Clearly, Mozart could rely on a much higher standard of the orchestral winds than he had experienced in Salzburg. The prominence of the winds is dramatically demonstrated in the second movement, which opens with a serene theme in the strings that comes to a dramatic and operatic stop. This is followed by an extended episode in which the strings play backup for the solo flute, oboe, and bassoon.

The opening movement unfolds in a relaxed and almost casually expressive mood. One gorgeous melody seems to chase the next, and the contrasting theme ventures into unexpected tonal areas. Instead of the expected rondo, the finale presents five variations on a simple tune but then pauses and seemingly jumps into an entirely new movement. Barbara Ployer played the premiere in June 1784.

Mozart benefited artistically and financially from his subscription concerts. And he certainly enjoyed his time as the darling of the Viennese concert scene. The Piano Concerto No. 19 premiered in the spring of 1785, possibly one of the busiest periods of Mozart’s life as a performer. Leopold came for a ten-week visit and was struck by the level of activity. “Every day, there are concerts, and the whole time is given up to teaching, music, composing and so forth. Since my arrival, your brother’s fortepiano has been taken at least a dozen times to the theatre or some other house.”

As Alfred Brendel writes, “the first movement of K. 459 is remarkable; no other movement in the whole series of twenty-three piano concertos evinces such subordination on the part of the piano to the orchestra: purely solo passages are rare, and for much of time the solo instrument is occupied in providing an accompaniment to various sections of the orchestra, notably the woodwinds.” That opening movement, unusually, also relies entirely on one theme, a march-like melody that dominates proceedings.

The slow movement forgoes a development section and sounds like a close collaboration among the soloist, the strings and the winds. That dialogue between the instrumental forces culminates in a final coda. The sonata-rondo finale seems a fitting conclusion as it playfully takes us into the world of opera buffa.

Mozart entered the Piano Concerto in D Minor, K. 466, in his new catalogue of compositions on 10th February 1785. It is the first of his piano concertos in the minor key. To be sure, the minor tonality adds a new dimension of high seriousness to the form, a mood immediately heard in the dramatic orchestral opening. The concerto is scored for trumpets and drums, as well as the now usual flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons and horns, with strings, and the violas divided.

Leopold Mozart was present at the premiere, and he wrote to his daughter, “We drove to Wolfgang’s first subscription concerto, at which a great many members of the aristocracy were present… Then we had a new and very fine concerto by Wolfgang, which the copyist was still copying when we arrived, and the rondo of which your brother did not even have time to play through as he had to supervise the copying.” Isn’t it amazing that in about three weeks, Mozart was able to write the most perfect and most passionate of concertos?

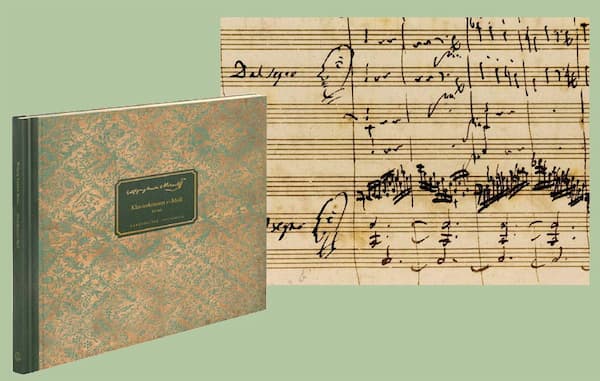

Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 20 autograph score

The D-minor concerto was a turning point as it was Mozart’s first “symphonic” concerto. The orchestra is given a completely equal position, and the wind parts become even more weighty. The sense of drama is evident in the large-scale orchestral introduction, and many of the piano parts would comfortably fit into an operatic seria. However, they are much more than just a beautiful melody. A noted performer writes, “Mozart probably found in D minor the threatening and demonic colouring he was looking for. A very personal statement!”

Mozart completed his 21st Piano Concerto in C Major, K. 467, on 9 March 1785, exactly a month after the premiere of his first concerto in the minor key. Contrary to the dramatic narrative of K. 466, the C-Major Concerto is a work filled with humour that focuses on elegant simplicity. A critic reported that Mozart’s playing “captivated every listener and established Mozart as the greatest keyboard player of his day.” Leopold Mozart added that the work was “astonishingly difficult,” and it would be the last time that father and son would actually see each other.

Presently, this concerto is known as the Elvira Madigan Concerto because the use of the second movement contributed strongly to the mood of the film of that name. The work opens quietly, with unison strings setting an opera buffa stage. There is an air of anticipation as the winds once again play an important role. They initiate little fanfare, double the strings, or even capture centre stage with melodic interjections. The soloist enters with new and independent ideas and then follows its own path.

Soloist and orchestra have a unique relationship here as both forces seem primarily concerned with their own material. As Donald Francis Tovey writes, “In no other concerto does Mozart carry so far the separation between the two… Mozart has succeeded in making the piano as capable a vehicle of his thought as the orchestra.” The dream-like and elegant second movement provides for a nocturnal atmosphere, while the concluding “Rondo” returns us to the opening mood. Mozart borrowed a theme from his concerto for Two Pianos, K. 365, and the entire movement is based on that witty tune with plenty of scope for soloists and the orchestra to show their brilliance.

Mozart completed his Piano Concerto in A Major, K. 488, on 2 March 1786. It was designed for use in a series of three subscription concerts that Mozart had arranged for part of the winter season. Simultaneously, Mozart was busy working on his first Italian opera for Vienna, Le nozze di Figaro. Yet, times had changed. Only three years earlier, the Viennese public had lavishly acclaimed the piano concertos by the young virtuoso; now, they sought musical entertainment elsewhere.

The concerts were not well subscribed, but Mozart nevertheless went ahead “believing that he could seduce the public with his unquenchable ability to come up with something new and tantalising.” K. 488 has remained popular and frequently performed as it creates a sense of weightlessness. And the role of the piano becomes even more versatile. It functions as a solo instrument and accompanies the orchestra, but it also integrates into the orchestra. In a sense, it functions as an orchestral instrument.

In his orchestration, Mozart replaced the bright-toned oboes with clarinets, providing a much darker colouration. This is particularly evident in the passionate and richly chromatic slow movement in the unusual key of F-sharp minor. However, the orchestration remains essentially intimate, as Mozart foregoes trumpets and drums. The chamber-music feeling of the first two movements is reinforced by active interchanges between the woodwinds. The soloist initiates an extensive rondo finale that has the character of a fast stretta, all ending in a buffo-like coda.

The second piano concerto in the minor key, the Concerto in C-minor, K. 491, was completed on 14 March 1786. It is scored for clarinets and oboes, flutes, pairs of bassoons, horns, trumpets and drums, and strings. It opens with an ominous theme that Beethoven would subsequently use as the inspiration for his C-minor Piano Concerto. A sense of foreboding permeates the entire movement, disturbed only momentarily by the tranquillity of the second theme.

Piano Concerto C minor K. 491 by W. A. Mozart

The ”Larghetto” movement opens in the major key, and episodes are framed by the principle melody. However, the music is soon led into the minor key by the woodwind, and a ray of serenity returns us to the opening. Mozart concludes this masterwork with a set of variations.

Piano Concerto No. 27 in B-flat Major, K. 595

Mozart completed the cycle of twelve Viennese concertos in December 1786. He waited almost 14 months to write another piano concerto, the so-called “Coronation.” Another three years passed before he brought this grand series to a close with the B-flat Major Concerto, K. 595. To scholars, this “work stands along, not only in terms of its chronological separation from the other piano concertos but because its content and character make it unique.” It is probably the most deeply personal of all Mozart concertos.

The clearly defined drama of the minor key concertos is replaced by what has been described as “a more personal notably resigned accent” and a feeling of “subdued gravity.” Mozart gave the premiere on 4 March 1791, and it was the last such appearance before the Viennese public. Alfred Einstein wrote, “it was not in the Requiem that Mozart said his last word… but in this work, which belongs to a species in which he also said his greatest.”

Friday, October 4, 2024

Who Was Mozart’s Real Musical Father?

by Janet Horvath, Interlude

Fans of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart will likely be aware that he was taught, shaped, and influenced by his father Leopold Mozart, a violinist and composer. When Leopold began to teach his seven-year-old daughter Nannerl, in 1759, he discovered that Wolfgang could imitate anything his sister played on the keyboard. Leopold began teaching the little boy, and in no time, Wolfgang made astonishing progress. Leopold, deciding the children’s exceptional talents had to be shown off, organized extensive concert tours of the continent, and the children impressed and amazed kings and queens with their music making.

Leopold Mozart © stringsmagazine.com

Wolfgang met many illustrious musicians while traveling in Europe and encountered the music of George Frideric Handel, Johann Sebastian Bach, Joseph Haydn, and Johann Christian Bach. Wolfgang’s friendship and musical kinship with Johann Christian (J.C.) Bach became pivotal.

Both Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Johann Christian Bach, were sons of famous musicians. J.C., the youngest son of Johann Sebastian Bach, was born in Leipzig. The elder Bach was by then fifty years old and in 1750, when J.C. was a young teenager, Johann Sebastian passed away. J.C. traveled to Berlin to live with his older brother and to further his studies in composition and on the keyboard with him, the eminent composer Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Johann Christian soon developed into an accomplished performer and composer in his own right. He began to travel widely, eventually settling in Italy.

Portrait of Mozart by Johann Nepomuk della Croce

Captivated by the new musical style he heard in the operatic music there—lyrical, charming, and effortless that shied away from the serious counterpoint of baroque music, J.C. began perfecting Stile galant. It was the music of the future, which introduced simple, graceful phrases that highlighted the melody. Johann Christian’s successful first operas were composed in this elegant style.

Appointed to the position of Music Master to Queen Charlotte, he moved to London in 1762. His reputation increased after writing several successful operas. In 1764 “The English Bach” met and mentored the young eight-year-old Wolfgang and the two enjoyed improvising on the harpsichord. Nannerl, Mozart’s sister, wrote in her letters that Bach would sit Mozart in front of him at the keyboard. J.C. played one bar, then Mozart would elaborate on the next bar, ‘and in this way they played a whole sonata, and someone not seeing it would have thought that only one man was playing’.

Mozart’s predilection for wind instruments originates with J.C Bach. The latter thought the winds should be featured; they should carry the melody and not simply double melodic lines. In fact, J.C. Bach’s earliest opera was the first to include clarinets.

Portrait of Johann Christian Bach in 1776 by Thomas Gainsborough ©

Bach’s keyboard style also greatly influenced Mozart. Naturally Mozart and his sister played keyboard duets throughout their childhood, and Mozart’s sparkling and enchanting compositions for piano four hands and for two pianos will always be celebrated. Piano duos or works for piano four hands are performed on one piano and differ from compositions that are written specifically for two pianos. Mozart wrote his Fugue in C minor K. 426, and his Sonatas in D major K. 448 and in C major K. 545 for two pianos, and many other composers from Ravel to Liszt, and Brahms to Rachmaninoff followed suit.

At the Duo Pleyel concert

It was enlightening to hear the two composers, Mozart and J.C. Bach, juxtaposed, and to hear Bach’s influence firsthand in a recent concert by Duo Pleyel in Austria at the spectacular 12th century abbey Klosterneuburg, in Augustinus Hall. Pianists Alexandra Nepomnyashchaya and Richard Egarr presented a program entitled “Mozart’s Real Musical Father” that alternated Piano Duets by W. A. Mozart and those by J.C. Bach. They performed on a replica of Chopin’s preferred piano, a Pleyel built in 1848.

The duo opened the concert with the Mozart Sonata for Piano 4 Hands in D Major, K. 381. I think you’ll agree the first movement Allegro could not be more beguiling. Within the movement the interlocking melodies alternate from the major and minor key effortlessly, moving from charm to mystery, and from affecting to poignant.

Stift Klosterneuburg

A delightful duo by Johann Christian Bach followed, the Sonata for Piano Duet in A major Op. 18, No. 5. The duo is only two movements. The allegretto is expressive and lyrical, with the two pianos evenly matched singing through beautiful scale passages and ornaments, certainly an example of Stile galant and the compositional style Mozart would emulate.

Mozart’s Five Variations in G Major for Piano Duet, K. 501 was next on the program. Mozart’s wizardry in this brief work of only 7 minutes, is riveting. He highlights and embellishes the initial enchanting melody first in eight notes, then in triplets in the lower piano line, then in sinuous sixteenth notes in the higher register. It’s followed by a slow and weightier variation in the minor key. More virtuosic flourishes follow before the simple version from the introduction returns towards the end and fades out gracefully. It’s masterful.

Acciacatura

The Sonata for Piano 4 Hands in F Major, K. 497 by Mozart begins with an exquisite Adagio before it embarks on a lighthearted Allegro di molto. What could be more beautiful than this opening? Mozart composes with such brilliant panache. Listen for the acciaccaturas – grace notes played as quicky as possible before the main note with the emphasis on the main note, as if little birds are chirping—as well as the speedy turns—a four-note pattern where the main note is played, then the note above, followed by the main note again, and then the note below, and is notated by a sideways ‘S’ symbol.

J.C. Bach Sonata for Piano Duet in F Op. 18, No. 6 followed, a work of only two movements, an Allegro, and a Rondeau-Allegro, which is an animated movement featuring unison playing and short cadenzas. One can hear many similarities in style that Mozart later adopted and perfected.

The concluding piece on the program, W.A. Mozart Sonata for Piano Duet in B-flat, K 358, begins with a lively and vivacious Allegro that highlights scales and unison passages in each of the two parts.

The third movement, a captivating Molto presto, features long passages of repeated notes, light and quick staccato notes, sparkling ornaments, rhythmic accents on the offbeats, low register bombast, all in merely three minutes. It must be so much fun to play, and lovely to listen to.

To hear these piano duos and to see the parallels between the composers in this most enjoyable program was illuminating, and evidence of the musical kinship between J.C. Bach and W. A. Mozart.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)