What does the muse of music look like? In the imagination of countless painters, that essentially abstract concept was depicted by a graceful yet stern and beautiful female figure holding or playing a musical instrument. Reality, however, can be a somewhat sobering experience, and on occasion, the musical muse turned out to be a portly, epileptic and sickly bloke. Such was the case with Rudolph, Archduke of Austria. He was a noble Habsburg by birth, a Cardinal-Archbishop by career and a patron of music by heart. He was brought to Vienna in 1792 when his eldest brother, Archduke Franz, became Emperor. As a child, Rudolph showed an exceptional talent for music and, at 15, was performing as a pianist. He met Ludwig van Beethoven in the winter of 1803/4 and began piano and theory lessons, followed shortly by lessons in composition. Beethoven dedicated 11 of his greatest compositions to Rudolph, including the famous “Archduke” Trio.

Archduke Rudolf

Under Beethoven’s guidance, Rudolph improved steadily as a pianist, and he premiered the violin sonata Op. 96 of his teacher. A critical observer wrote, “the performance as a whole was good, but we must mention that the piano part was played far better, more in accordance with the spirit of the piece, and with more feeling than that of the violin.”

Archduke Rudolph also has the unique distinction of being Beethoven’s only composition student. In two decades of study, Rudolph produced a sizable and well-crafted body of music for piano, chamber ensemble, and voice. Never venturing beyond traditional forms, genres and the harmonic language of the period, Rudolph nevertheless had a strong lyrical voice. A good many of the Archduke’s autographed manuscripts, currently held at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, show corrections, suggestions, and emendations in Beethoven’s hand.

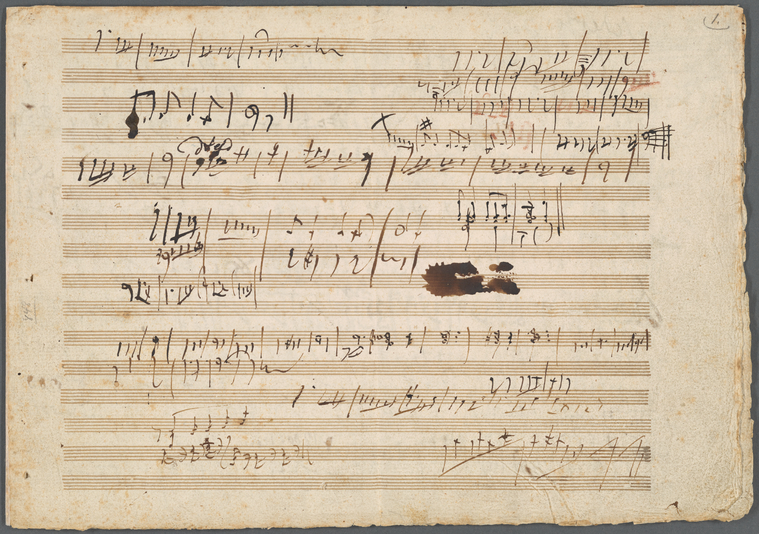

Sketches for Beethoven’s Archduke Trio

In 1809, Beethoven was offered a proper job. King Jerome of Westphalia, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, offered Beethoven the position of Kapellmeister at the court in Kassel. That appointment, with very few obligations attached, was worth about 3,400 florins annually and promised for life. Beethoven had no intention of leaving Vienna, and he now used the Kassel figures to obtain a matching offer from Vienna.

Archduke Rudolph persuaded Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Kinsky to contribute annually for a guaranteed salary of 4,000 florins, and Beethoven remained resident in Vienna for the rest of his life. One way of thanking the Archduke for any financial commitments or other favours was to dedicate music specifically to him. And that was also the case with Baron Heinrich Eduard Josef von Lannoy. A member of one of the oldest families in Belgium, Baron Heinrich spent most of his life in Austria, and he dedicated his clarinet trio to his friend the Archduke Rudolph.

Baron Heinrich Eduard Josef von Lannoy

In early 1825, Schubert began to write piano sonatas for the first time, which he intended to publish. He composed six sonatas in the four-movement format pioneered by Beethoven and started to look for a publisher. In the end, Schubert selected three sonatas and originally planned to issue them as a group dedicated to Hummel. However, he eventually changed his mind, and a different Viennese publisher issued each work separately. And the dedication to Hummel—at least in the case of D. 845—was dropped in favour of Archduke Rudolph. The Archduke took a bit of time before accepting the composition, but in the end gave his seal of approval. By that time, Archduke Rudolph had abandoned a career in the army for a much less strenuous one in the church. He died at the early age of 43 and ordered that his heart should be entombed in the cathedral at Olmötz and his body buried in the Imperial vault at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

No comments:

Post a Comment