It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, June 29, 2025

Anne-Sophie Mutter, Daniel Barenboim, Yo-Yo Ma – Beethoven: Triple Concert

Sunday, June 22, 2025

Friday, May 9, 2025

Yunchan Lim piano - Beethoven Piano Concerto No 3 from 2022 Yeulmaru New...

Thursday, March 20, 2025

Beethoven | Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Piano in C major "Triple Concert

Friday, July 19, 2024

Archduke Rudolph of Austria: The Sickly Muse

What does the muse of music look like? In the imagination of countless painters, that essentially abstract concept was depicted by a graceful yet stern and beautiful female figure holding or playing a musical instrument. Reality, however, can be a somewhat sobering experience, and on occasion, the musical muse turned out to be a portly, epileptic and sickly bloke. Such was the case with Rudolph, Archduke of Austria. He was a noble Habsburg by birth, a Cardinal-Archbishop by career and a patron of music by heart. He was brought to Vienna in 1792 when his eldest brother, Archduke Franz, became Emperor. As a child, Rudolph showed an exceptional talent for music and, at 15, was performing as a pianist. He met Ludwig van Beethoven in the winter of 1803/4 and began piano and theory lessons, followed shortly by lessons in composition. Beethoven dedicated 11 of his greatest compositions to Rudolph, including the famous “Archduke” Trio.

Archduke Rudolf

Under Beethoven’s guidance, Rudolph improved steadily as a pianist, and he premiered the violin sonata Op. 96 of his teacher. A critical observer wrote, “the performance as a whole was good, but we must mention that the piano part was played far better, more in accordance with the spirit of the piece, and with more feeling than that of the violin.”

Archduke Rudolph also has the unique distinction of being Beethoven’s only composition student. In two decades of study, Rudolph produced a sizable and well-crafted body of music for piano, chamber ensemble, and voice. Never venturing beyond traditional forms, genres and the harmonic language of the period, Rudolph nevertheless had a strong lyrical voice. A good many of the Archduke’s autographed manuscripts, currently held at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, show corrections, suggestions, and emendations in Beethoven’s hand.

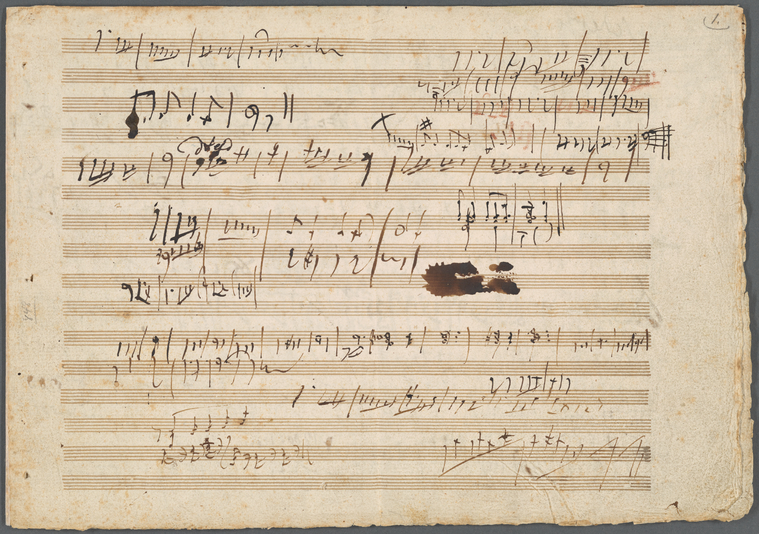

Sketches for Beethoven’s Archduke Trio

In 1809, Beethoven was offered a proper job. King Jerome of Westphalia, brother of Napoleon Bonaparte, offered Beethoven the position of Kapellmeister at the court in Kassel. That appointment, with very few obligations attached, was worth about 3,400 florins annually and promised for life. Beethoven had no intention of leaving Vienna, and he now used the Kassel figures to obtain a matching offer from Vienna.

Archduke Rudolph persuaded Prince Lobkowitz and Prince Kinsky to contribute annually for a guaranteed salary of 4,000 florins, and Beethoven remained resident in Vienna for the rest of his life. One way of thanking the Archduke for any financial commitments or other favours was to dedicate music specifically to him. And that was also the case with Baron Heinrich Eduard Josef von Lannoy. A member of one of the oldest families in Belgium, Baron Heinrich spent most of his life in Austria, and he dedicated his clarinet trio to his friend the Archduke Rudolph.

Baron Heinrich Eduard Josef von Lannoy

In early 1825, Schubert began to write piano sonatas for the first time, which he intended to publish. He composed six sonatas in the four-movement format pioneered by Beethoven and started to look for a publisher. In the end, Schubert selected three sonatas and originally planned to issue them as a group dedicated to Hummel. However, he eventually changed his mind, and a different Viennese publisher issued each work separately. And the dedication to Hummel—at least in the case of D. 845—was dropped in favour of Archduke Rudolph. The Archduke took a bit of time before accepting the composition, but in the end gave his seal of approval. By that time, Archduke Rudolph had abandoned a career in the army for a much less strenuous one in the church. He died at the early age of 43 and ordered that his heart should be entombed in the cathedral at Olmötz and his body buried in the Imperial vault at St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna.

Monday, May 20, 2024

A message to humanity: Symphony No.9 by Ludwig Van Beethoven.

Friday, May 3, 2024

200th Anniversary of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony

by Georg Predota, Interlude

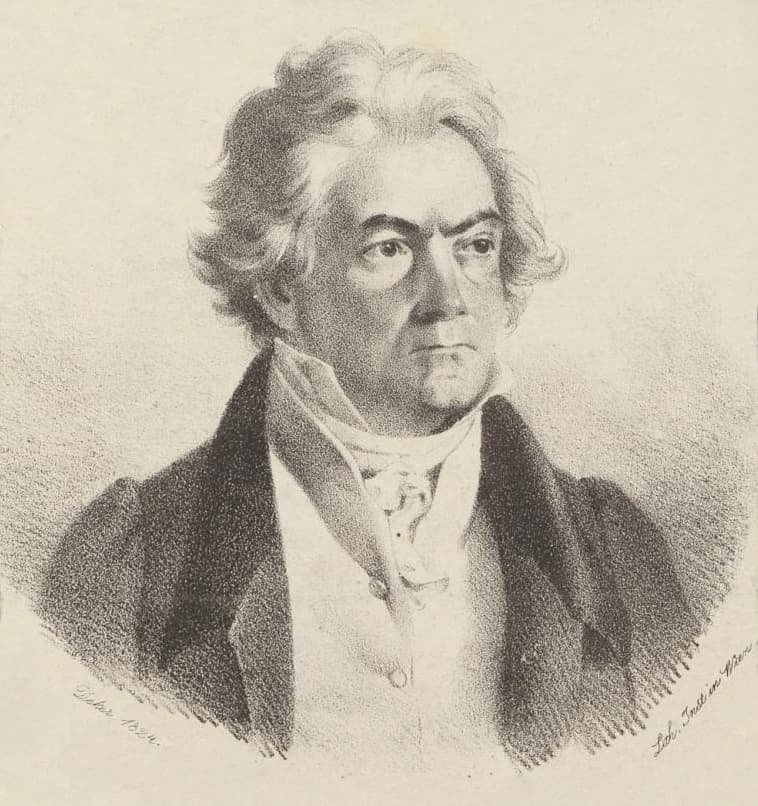

Ludwig van Beethoven in 1824

To commemorate the 200th anniversary of this memorable event, the Beethoven-Haus Bonn has organised an extensive and multi-faceted 10-day anniversary programme. Visitors and enthusiasts, onsite and online, are treated to exhibitions, a book presentation and signing, a conference, various exhibitions, concerts, and livestreams. At the heart of the celebration is the re-creation of the 7 May 1824 concert at the Stadthalle Wuppertal.

7 May 1824

Beethoven-Haus Bonn

In 1824, Beethoven assembled a large orchestra and recruited Henriette Sontag and Caroline Unger to sing the soprano and the contralto parts, respectively. According to participating musicians, the 9th Symphony had only two full rehearsals, and was prefaced by the Overture Op. 124 and the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei from the Missa Solemnis. Unsurprisingly, various stories and anecdotes surrounded this momentous occasion. Beethoven, stone deaf at this time, actually took part in the performance by giving the tempos for each part and turning the pages of his score “as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts.”

However, the official conductor Michael Umlauf, had instructed the singers and musicians to ignore all of Beethoven’s instructions. When the concert had ended, Beethoven was still conducting and Caroline Unger is credited with turning Beethoven to face the applauding audience. Beethoven’s underlying conception of music as a mode of self-expression still resonates strongly today, and whether one agrees with, or rejects his compositional approach, after him, nothing in music could ever be the same.

7 May 2024

Martin Haselböck

200 years later, the complete premiere performance will be reconstructed by the Orchester Wiener Adademie, considered one of the leading period-instrument orchestras. Soloist and the WDR Rundfunkchor under the musical direction of Martin Haselböck invite audiences to the 19th-century historical City Hall in Wuppertal to experience the original programme in its original order and its entirety. This promises a unique and rather lengthy listening experience, and one that will undoubtedly provide a new and unique perspective.

As the Director of the Beethoven-Haus Bonn, Malte Boecker explains, “to mark its 200th anniversary, we are presenting the Ninth for the first time in the sound of 1824 again as well as in the probable instrumentation, the line-up and the programmatic arrangement that Beethoven himself had planned.” Researchers and scholars have been able to reconstruct a number of facts regarding the original performance. Apparently, the choir had been positioned in front of the orchestra and not as we have come to expect, behind the instrumental forces. Additional research has suggested a possible instrumentation described by Beethoven, and important new details regarding the musical text.

Romantic Historiography and Meaning

Caroline Unger

According to the organisers of the anniversary concert, “in terms of content and aesthetics, the reconstructed programme shows a variety of relationships and suggests that Beethoven wanted to appeal to the idea of Eternal Peace with the Academies.” By definition, ascribing meaning to a programme and/or a particular work is a slippery subject, as we can interpret Beethoven’s meaning in endless ways. It all depends on our interests as modern reconstructions, while historically informed, are essentially restorations according to contemporary attitudes and tastes.

The recasting of this event in the tradition of terms and meanings is not really a historical project, since the concept of historiography was invented long after Beethoven’s death. It is simply impossible to ascribe a definite meaning to Beethoven’s programme or symphony, nor is it possible to deny the symbolic dimensions of the evening and the work. That is probably why a critic once wrote, “Beethoven’s 9th Symphony is a piece one loves to hate: It’s incomprehensible and irresistible, it’s awesome and naïve.”

Berlin Premiere

Henriette Sontag

It might be worth remembering that Beethoven was adamant that his 9th Symphony should be premiered in Berlin and not in Vienna. His threat to take his symphony to Berlin was real enough as it took a petition signed by many prominent Viennese patrons, friends, financiers and performers for the composer to change his mind.

Why then was Beethoven so unhappy with Vienna? For some years the composer had lamented the changing musical taste of Viennese audiences, who numerously flocked to see the operatic entertainments offered by Rossini and other Italian composers. Beethoven and Rossini probably met once in Vienna in 1822, and supposedly Beethoven counselled his young colleague with the words, “Above all, make a lot of Barbers!”

Ode to Joy

For Beethoven, Rossini was a composer of light comedies, who embraced the “rankest lap of luxury” by pandering to populist demands. Supposedly, Beethoven quipped “Rossini would have been a great composer if his teacher had spanked him enough on the backside.” Whether this meeting and conversation actually took place or not is clearly beside the point, as it quickly became, and still is, part of a much larger narrative.

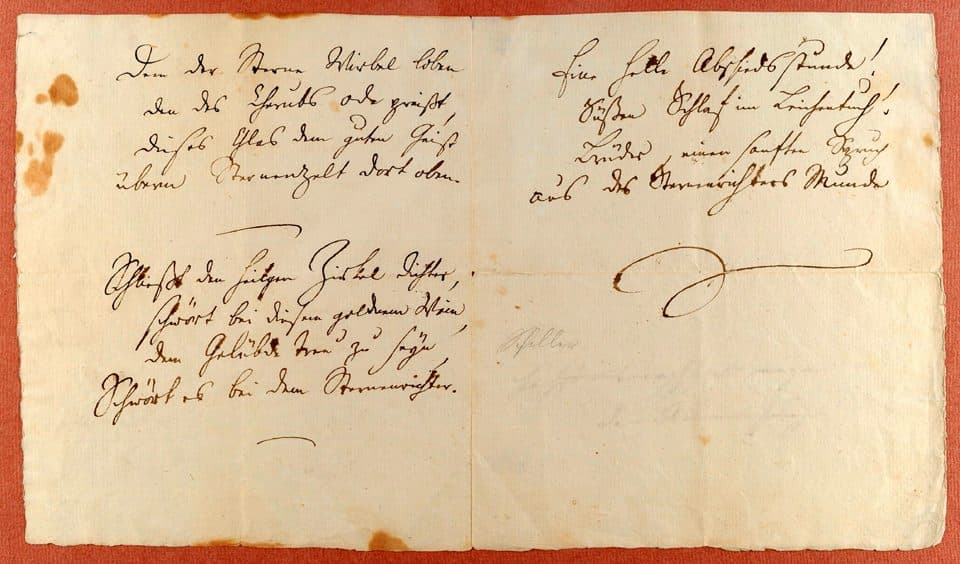

Schiller’s Ode to Joy

By presenting his Ops. 123, 124, and 125 in a single academy, Beethoven was clearly not trying to appeal to popular demands. Rather the opposite, it seems, as a programme of such seriousness, duration and ticket expense, was hardly going to attract the bohemian party crowd. By appealing to the spirit of Romanticism and the shared ideals of humanity as expressed in Schiller’s Ode to Joy, the composer appeared to have made not only a musical point but also issued a decisive cultural statement.

200 years later, the Ode to Joy is the anthem of both the European Union and the Council of Europe. Its described purpose is to “honour shared European values, expressing the ideals of freedom, peace, and unity.” The 2024 re-creation of the 1824 academy still won’t be a crowd magnet, nor will it be an attractive event for most Europeans. However, the statement of intent seems very clear. The utopian ideals expressed in the 9th Symphony, although no longer believable in 2024, still need to provide the fundamental bases of interaction in a world intent on proving the opposite on a daily basis.

Wednesday, February 28, 2024

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 | Margarita Höhenrieder, Staatskapelle Dresden

Wednesday, January 31, 2024

Anne-Sophie Mutter, Daniel Barenboim, Yo-Yo Ma – Beethoven: Triple Concert

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Beethoven - 5th Piano Concerto 'Emperor'

Monday, February 27, 2023

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major op. 58 | Y. E. Son

Thursday, February 16, 2023

Thursday, February 2, 2023

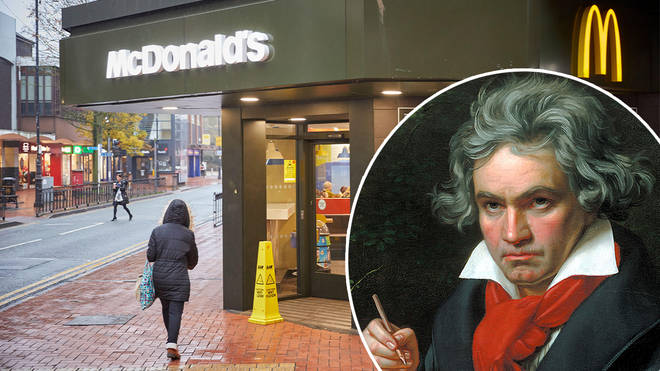

McDonald’s restaurant in Wales to play Beethoven to tackle late-night antisocial behaviour

By Maddy Shaw Roberts, ClassicFM

A Welsh branch of the fast-food chain will soon start piping in the music of Beethoven, in a bid to tackle antisocial behaviour.

Frequenters of a branch of McDonald’s in Wales will soon have a symphonic accompaniment to their quarter-pounders and fries.

McDonald’s in Wrexham is set to introduce the music of Beethoven in an attempt to combat persistent issues with gangs of young people.

Classical music will be heard at the fast-food restaurant in north Wales from 5pm, following multiple reports of issues including an assault involving at least 20 people when staff were hit with coins.

North Wales Live reports that police inspector Luke Hughes said they had received “multiple reports... of one particular group of youths, that at times numbered 20-30, roaming between locations”.

“There was more than one allegation of assault, a fire extinguisher set off, signs and coins thrown at shop staff and younger children chased by this group,” he added.

The restaurant will also restrict its WiFi service in an attempt to deter the troublemakers.

Hughes later said: “I also want to thank those businesses that I had written to earlier in the week. I had a great response, with some imposing entry conditions.

“A well-known fast-food retailer will be playing classical music from 5pm in the evening, so unless we have some local and unruly Beethoven enthusiasts, it should discourage some issues.”

For more than a decade, McDonald’s and other fast-food chains have been opting for classical music to calm hungry patrons, relax those waiting for food and help tackle antisocial behaviour.

McDonald’s has previously said: “We have tested the effects of classical music in the past and played it in some of our restaurants as it encourages more acceptable behaviour.

“Typically, classical music would be played from early evening onwards and, in some cases, on certain nights in a small number of restaurants.”

A branch in Shepherd’s Bush, which had 71 reports of crime in or near the store in 2017, saw its crime rate fall significantly after classical music was introduced, according to the manager.

Atul Pathak, who operates several restaurants in the capital, said at the time: “Working together with the police and the local council in Shepherd’s Bush to help them with combating persistent antisocial behaviour, we thought that playing classical music at certain times of the day would help to set a different and calmer tone.

“It is working really well and has been positively received by many customers, so much so that we are giving real consideration as to where else we might introduce it.”

While McDonald’s Wrexham won’t be the first fast-food restaurant to use classical music to calm its potential customers, it remains to be seen whether the composer’s symphonies will help the branch achieve its desired outcome. They may be wise to steer clear of this rather glorious 10,000-person take on the ‘Ode to Joy’.

Listen to this 10,000-strong Japanese megachoir sing Beethoven’s ‘Ode to Joy’

By Sophia Alexandra Hall

@sophiassocialsOver a century ago, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony reached Japan in an unexpected way. Today, it’s one of their most celebrated pieces of repertoire, and there’s a very particular performance of it once a year we think you should see.

When Beethoven wrote his Ninth Symphony, he probably had no inkling of the worldwide phenomenon the triumphant choral climax of his work would become.

The final movement of his final symphony, or as it’s more commonly called, ‘Ode to Joy’, has its vocal libretto taken from a 1785 German poet Friedrich Schiller of the same name.

The choral work’s lyrics are often associated with messages of freedom, hope, and unity, and when sung by a large chorus to Beethoven’s simple stepwise melody, have great power and resonance across the world.

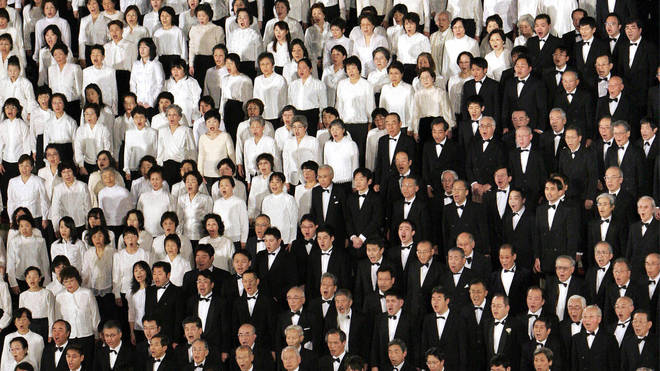

And no performance is arguably more powerful than that of a choir totalling over 10,000 singers.

In Japan, every December, ‘Ode to Joy’ is sung all across the country, but the most notable performance takes place once a year, when 10,000 singers join together to sing the German composer’s most famed vocal work.

A performance like this can’t accurately be described any other way, than by listening. Watch it below...

This particular performance, recorded in December 2012, was conducted by Yutaka Sado – a Japanese conductor who studied under Leonard Bernstein and Seiji Ozawa.

Along with professional soloists, a smaller chamber choir and an orchestra, the remaining singers in the 10,000-strong choir are all untrained, or amateurs who wish to take part in the annual ‘Daiku’ (translated literally as number nine, in reference to Beethoven’s symphony).

‘Ode to Joy’ is sung by the Japanese choir in German, and the singers taking part in the event spend anywhere from between weeks and months preparing to sing in the original language.

It is a privilege to be chosen to sing as part of the 10,000-voice choir, as the chance to perform with the ensemble is oversubscribed every year. The first time the choir sang with over 10,000 members was during the coronavirus pandemic, when 11,961 voices joined virtually around the world to celebrate Beethoven’s 250th birth year.

But why Beethoven? Ode to Joy’s significance in Japan

How Beethoven’s vocal work arrived in Japan is a solemn story which originates during the First World War.

During this war, Japan and Germany were enemies, and approximately 1,000 German soldiers were captured from the German-occupied Chinese island of Qingdao, and taken to a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in 1914.

Subsequently, ‘Ode to Joy’ is said to have arrived in Japan via these German prisoners, who would sing the Beethoven masterwork while being held in Naruto’s Bando War Camp.

By 1918, the war camp had taken on more prisoners. And in July of that year, one German prisoner of war led an orchestra (made up of mostly handmade instruments) of 45 prisoners, and an 80-strong all-male choir, in a performance of the Ninth.

News of this concert spread across Japan, and by 1925, the first known performance of the Ninth by Japanese musicians was performed by students at the predecessor of the Tokyo University of the Arts.

Over 100 years since the Bando prison camp was destroyed, remnants of that first musical exchange remain in modern day Naruto.

A roadside station named the ‘Home of the Ninth’ stands in Naruto today, selling German sausages among the usual goods found in such stores. The building is notably constructed from the original parts and materials used in the prisoner-of-war camp.

A statue of Beethoven also stands nearby, erected in 1997 by German sculptor Peter Kuschel. Surrounding the statue are pictures taken at various anniversary concerts, marking the first performance of his Ninth in Asia in that prison camp in 1918.

Despite its solemn beginnings, the Ninth has become a staple of Japan’s performance repertoire. And with its themes of friendship, fellowship, and unity, it’s no wonder this choral work is still so widely performed all across the world today.