by Georg Predota, Interlude

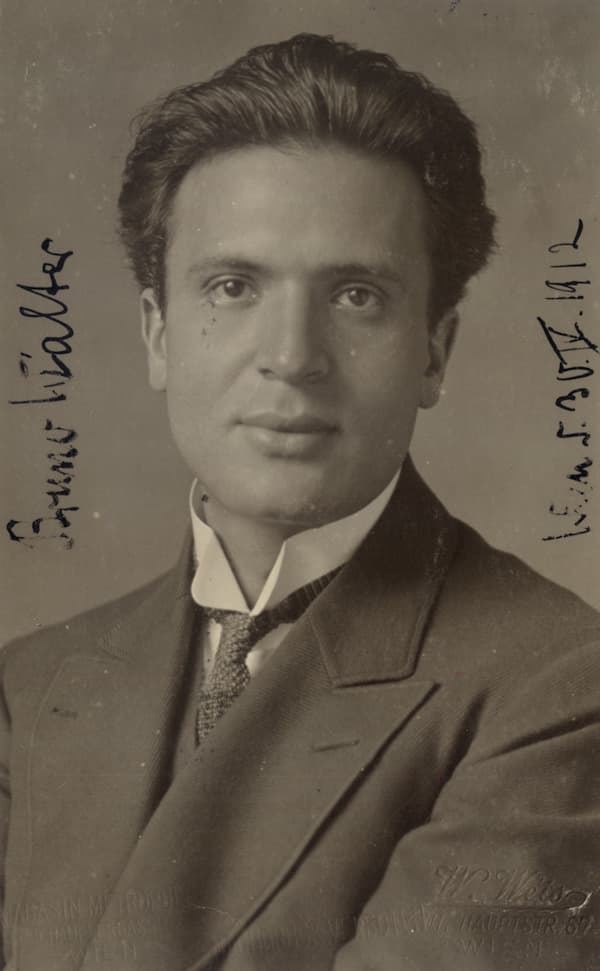

Bruno Walter in 1912

For one, Walter was a founding member of the “Society of Creative Musicians,” founded in 1904 and championed by Alexander von Zemlinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, with Gustav Mahler as the honorary president. The musicologist Guido Adler wrote, “the society aims to give contemporary music an ongoing platform and to keep the concert-going public abreast of current developments in music composition.”

From his earliest days at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin, Walter was interested in composition as he “covered innumerable sheets of music of all kinds… none of them remarkable.” Initially, Walter prepared for a pianistic career but eventually turned towards composing and conducting. His composition activity flourished during his early years in Vienna, and in an article by the Mahler biographer Richard Specht, Walter was counted among the progressive composers of the day.

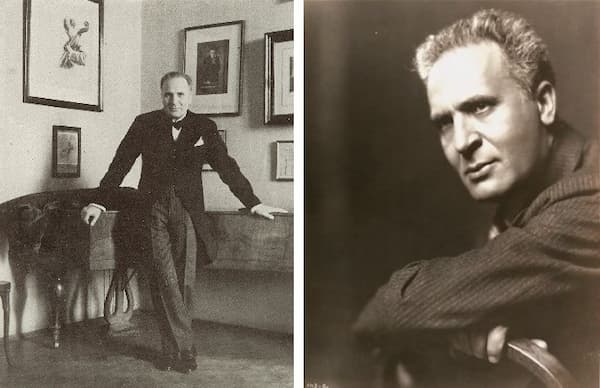

Arnold Rosé

Arnold Rosé

In 1901, Walter was appointed at the Vienna Court Opera at the request of Gustav Mahler. Walter knew Mahler from Hamburg, and he described him as a man “who renewed himself every minute, and who did not know the meaning of slackening either in his work or in his vital principles.” However, Walter initially built his most intense artistic relationship with the violinist Arnold Rosé, concertmaster at the Vienna Philharmonic and leader of a famed string quartet that bore his name.

As Walter writes in his autobiography, “I shall never forget the sublime beauty of his violin solos, and the magic of Rosé’s playing lost none of its enchanting effect on me in the course of a great many years… Never for a moment did the high tension of his playing relax, whether at rehearsals or performances…His musicianship was innate and intuitive, his intonation and sense of rhythm were infallible, and he was gifted with a perfect ear.”

As such, it is hardly surprising that the Rosé Quartet premiered Walter’s String Quartet in D Major on 17 November 1903. Walter told his friend Hans Pfitzner after the premiere, “Rosé performed my quartet exquisitely. The audience received the first two movements warmly, then listened to the third (most important) movement with icy silence, and the last movement ultimately unleashed a veritable battle; the press was at a total loss but were respectful.” The work was never performed again, and parts of the autograph score were presumed lost. Fortunately, a copy of the entire composition has recently been unearthed in Vienna.

Piano Quintet

Bruno Walter

The Rosé Quartet with the composer at the piano also performed the premiere of Walter’s Piano Quintet in F-sharp minor on 28 February 1905. This substantial four-movement work is modelled in the tradition established by Schumann and Brahms, and written in a late-Romantic style. As Wolfgang Klos writes, “the work is dedicated to Nina Spiegler (née Hoffmann), who almost became Mahler’s sister-in-law and whose salon brought together the leading intellectuals in Vienna at the turn of the century, including Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Karl Kraus, Alfred Polgar, Peter Altenberg and Arthur Schnitzler.”

Walter composed dense and propulsive outer movements, “tossing out ideas like darts that don’t consistently strike nor stick to the intended target.” Cast in three parts, the second movement marked “Ruhig und heiter” has melodic touches reminiscent of Mendelssohn punctuated by a fiery central section. I hear a bit of Mahler in the third movement, also in three parts, but it seems rather overly busy in parts.

The work was reasonably well received, but it has only recently been recorded. In addition, Universal Edition was an early publisher of Walter’s work, and they have finally issued the first edition as well. Contemporary reviews have been lukewarm at best, describing the Quintet as “a mess with clunky scoring and a dense and opaque texture. Walter chose the right career path.”

Symphony No. 1

Bruno Walter was intimately connected with premiere performances of the symphonies of Gustav Mahler, and he started work on his own Symphony No. 1 in 1906. He played through the work for Mahler in September 1907, but it clearly failed to make an impression. As Mahler wrote to his wife, Alma, “Unfortunately, it means nothing to me, and my frank opinion put him in a state of mild despair.”

The work did premiere on 6 February 1909 at the Vienna Musikvereinssaal with the composer conducting. As Erik Ryding notes, “A large and ambitious work, the symphony runs for nearly an hour, and shows Walter completely in control of his massive forces. For a first symphony, it is a remarkably advanced piece with well-wrought counterpoint and ingenious motivic development both within and across movements. The angular, chromatic lines and the sometimes-tortured atmosphere, specifically in the opening movement, may come as a surprise.”

A critic suggested that “Walter’s music strives to capture chivalric feeling, battle, glory, power, heroic victory and death,” sentiments that do seem to capture much of Walter’s musical expressions. However, Vienna’s most feared critic at the time, Julius Korngold wrote, “Walter’s themes seem artificial, not naturally grown…twisting laboriously, saying little of significance. Even the development, the structuring, indeed the use of material … are lacking in clarity and a deeper inner logic.” Erik Ryding disagrees, and sees the symphony not as an imitation of Mahler, but an original symphony that marks a significant step forward in style.

Lieder

Bruno Walter was a voracious reader who developed a passion for literature during his early years at school. He devoured the poetically inspired fairy tales of Andersen and the collection of Grimm, and he was soon captivated by the fabulous works of Greek mythology. As he recalls in his autobiography, “when I was nine or ten, the attraction to my juvenile books began to fade, and I felt drawn towards the treasures in my parents’ bookcase.”

He was soon reading Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Heine, Hauff, Rückert and Shakespeare. As he recalled, “my early eagerness for and susceptibility to the drama and my inclination to identify myself with literary figures clearly indicate a dramatic vein in my mental endowment. No wonder then that at the very beginning of my career, I was irresistibly drawn toward the opera.”

Walter soon graduated to a “well-ordered and profound cultivation of beloved authors,” and he found his way into poetry. Besides Goethe, “whose works implanted in me a passionate desire for self-education and the systematic development of my talents,” he became fond of the poetry of Joseph von Eichendorff. Predictably, Walter set a number of poems to music, and the featured Eichendorff selection bears the clear musical influence of Gustav Mahler.

Violin Sonata in A Major

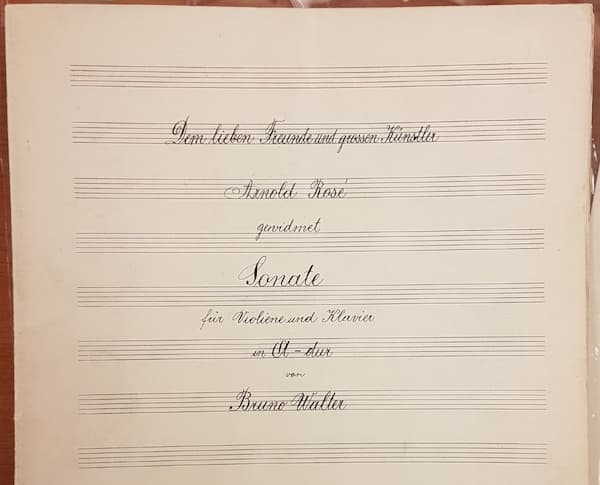

Bruno Walter’s Violin Sonata score

The Sonata for Violin and Piano in A Major, premiered by and dedicated to Arnold Rosé, first sounded on 9 March 1909 with the composer at the piano. The dedication reads, “For my dear friend, the great artist Arnold Rosé.” This would be Walter’s final chamber music composition and the only one published during his lifetime.

The expansive opening movement provides for a rather complicated motivical development, while the “Andante” undergoes a series of mood changes that place serious technical demands on the performers. The “Finale” unfolds in the manner of a Rondo, with the refrain shared between the violin and the piano.

As Erik Ryding noted, “Walter composed in a post-Romantic, expressionist vein, and his well-crafted works are often thick-textured, ecstatic outpourings.” Walter emphatically stated later in life, “I am not a composer… yet there was a time when I still entertained the illusion of being one.”