It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Showing posts with label Peter I. Tschaikowsky. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Peter I. Tschaikowsky. Show all posts

Sunday, July 27, 2025

Friday, February 7, 2025

From John Field to Alexander Scriabin: The Russian Nocturne

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

In our last blog we listened to some of the most beautiful Nocturnes by John Field. He is considered the father of the Nocturne, and his smaller-scale character pieces emerged from a growing salon culture throughout Europe. Field made fantastic use of the technical improvements of the piano, now allowing for a more sustained legato, greater variety of touch, subtler range of dynamics and a highly efficient sustaining pedal.

Anton Wachsmann: John Field, ca 1820 (Gallica: btv1b84179686)

On occasion, one can still hear performances of the Field Nocturnes in the concert halls, but they seem to have been relegated to preparatory exercises for the magnificent Nocturnes of Frédéric Chopin. He took on the legacy of Field’s invention and took this new salon genre to a deeper level of sophistication.

In light of Chopin’s achievements, it is easy to forget that Field’s influence was also felt in Russia. Field made Russia his home between 1802 and 1829, and he was deeply admired as a performer. However, he also set up a highly successful private piano studio, which contributed to the establishment of the Russian piano school and to Russian music itself. Will you join me on a journey through the wonderful world of the Russian Nocturne?

The Glinka Connection

Michael Glinka: Nocturne in E-Flat Major

When I started looking for John Field’s Russian connections, I came across the marvellous website of pianist and scholar Daniel Pereira. He embarked on an ongoing 15-year research project that looks at the history of universal pianism and its interpreters and teachers. It’s called “Piano Traditions Through their Genealogy Trees” and features thousands of piano connections throughout time, including pianists, teachers and the establishment of national and regional schools of playing.

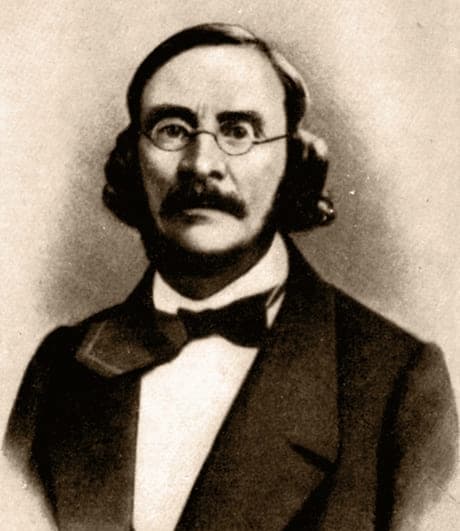

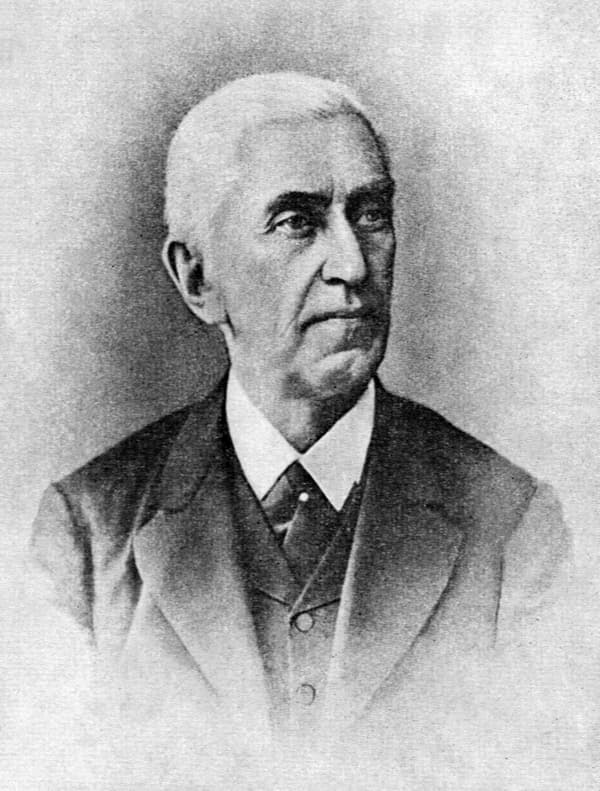

Mikhail Glinka

Thanks to Daniel Pereira, we can now trace the students of John Field and their role in the Russian Nocturne tradition. One of the biggest names to emerge is Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857), who is generally regarded as the father of Russian music. Apparently, Glinka had a number of piano lessons from Field, and we know that his operas “A Life for the Tsar” and “Lyudmila” are cornerstones of a Russian tradition.

Glinka was surprisingly well travelled, and he personally knew Donizetti, Bellini, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Auber, and Victor Hugo. But even more interesting for this blog, he also composed a number of piano pieces, including several Nocturnes. His “Nocturne in E-flat Major” dates from 1828 but was published only fifty years later. Some commentators call it “the first Russian Nocturne,” and the connection to Field is obvious. The beautifully flowing and melancholy Nocturne in F minor dates from 1839 and was written for Glinka’s sister while she was away, hence the title “The Separation.”

The Rubinstein Connection

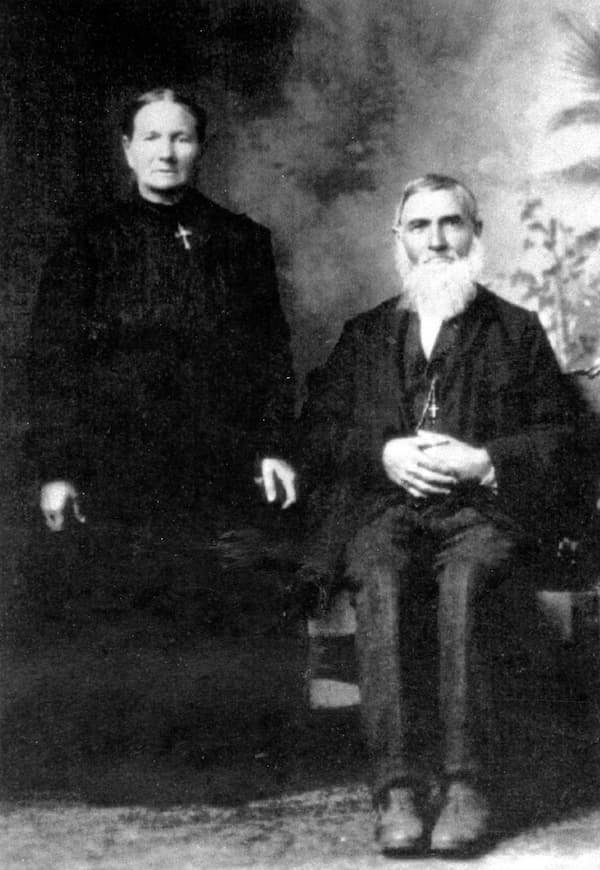

Alexander Villoing

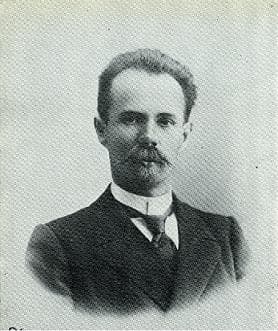

Alexander Villoing (1804-1878) was born of a French émigré family and he studied piano with John Field in Moscow. By 1830, in the tradition of his teacher, he had established his own piano studio and soon enjoyed a reputation as one of the best pedagogues in Russia. Most significantly, in 1837 he was tasked with teaching the eight-year-old Anton Rubinstein. In fact, he is still considered Rubinstein’s only teacher and one of his best friends.

Villoing accompanied his young charge on a European concert tour between 1840 and 1843. He once again toured with Anton, his brother Nikolai and their mother Kalerija Christoforovna between 1844 and 1846. And we know that he became a professor at the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1862, an institution founded by Anton Rubinstein.

Villoing not only taught at the St Petersburg Conservatory, he also published his “Piano School”, the École pratique du piano in 1863. That particular piano primer was also called “Exercises for the Rubinstein Brother.” It was adopted as the official piano method at the Conservatory, republished several times, and even translated into German and French.

Anton Rubinstein, 1842

As a student of Field, Villoing was almost certainly introduced to the Nocturnes, a tradition he passed on to Anton Rubinstein. Rubinstein started to compose at the age of 12 and established world fame as a pianist. However, he was always keen to establish himself as a composer, and “he was the first Russian composer whose works for solo piano embodied the same serious artistic ideas as his symphonies and chamber music.”

In all, Anton Rubinstein composed eleven Nocturnes, two of them for piano four hands. Thematically charming and pianistically perfect, the Rubinstein Nocturnes are written with great skill and refinement. A critic suggests, “rather than plumbing the deepest emotions, they are far above the average Romantic salon music.

The Tchaikovsky Connection

Anton Gerke

Among Field’s students, we also find the pianist, composer and teacher Anton Gerke (1812-1870). He was the son of a Polish violinist, and he personally knew Liszt, Thalberg, and Clara Schumann. I don’t know much about his apprenticeship with John Field, but by 1831 he was appointed court pianist in St Petersburg. Gerke was also involved with setting up the Russian Music Society.

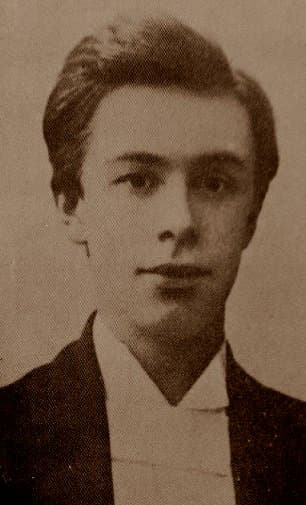

Anton Gerke taught at the St Petersburg Conservatory between 1862 and 1870, and among his students were Nikolay Zaremba, Nadeszhda Rimskaya-Korsakova, Modest Mussorgsky, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Of course, when we look at the Tchaikovsky connections, we also find Anton Rubinstein.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Two Pieces Op. 10, No. 1 “Nocturne in F Major”

Tchaikovsky and Anton Rubinstein did not get along at all. Tchaikovsky was a student in Rubinstein’s instrumentation classes in the conservatory’s first intake in 1862. Rubinstein was unquestionably the greatest pianist besides Franz Liszt, and he knew it. Rubinstein considered himself a successor of Schubert and Chopin, and he very much disliked Tchaikovsky’s music.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

As Tchaikovsky later wrote, “In my younger days, I very impatiently blazed my way—tried to acquire a name and fame as a composer—and hoped that Rubinstein would help me in my quest for laurels. But I must confess with grief that Anton Rubinstein did nothing, absolutely nothing, to further my desires and projects.”

Tchaikovsky composed his two Nocturnes in the 1870s, and “they are generally regarded as real jewels of Russian music.” He almost certainly knew the Nocturnes by Field, Rubinstein, and Chopin, but he also seems to take his bearing from Glinka. A pianist writes, “Tchaikovsky’s nocturnes abound with the heartfelt poetry of everyday life, and in following Field, places floating melodies above repeated pulsating chords.” Tchaikovsky also loved to place his melodies in the cello register of the piano, “creating an almost orchestral texture.”

The Glazunov Connection

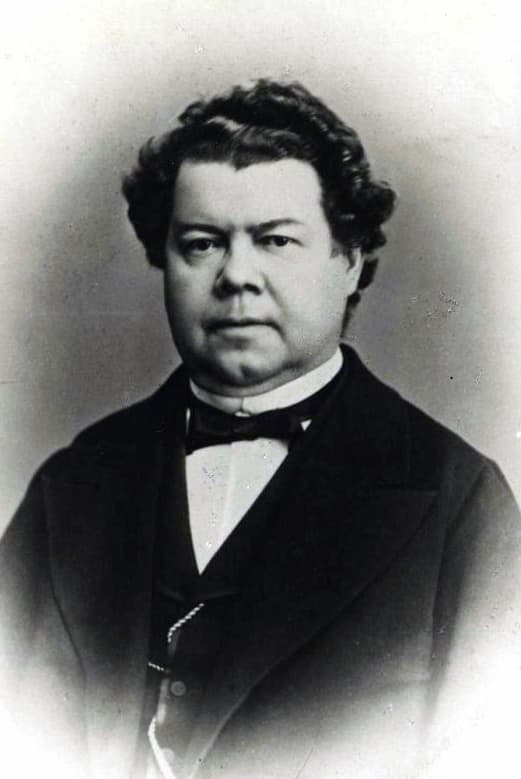

Alexander Dubuque

We must count the pianist and teacher Alexander Dubuque (1812-1898) among the most influential students of John Field. He was probably of French descent, and as one of the most influential teachers in Russia, Dubuque carried the piano tradition of John Field into the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Among his most distinguished students were Balakirev and Nikolay Zverev, the teacher of Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Ziloti. Dubuque was known for an intellectually controlled, poised and precise style that became associated with the Field-Dubuque Moscow tradition. He even published a book on the technique of piano playing and one on his “Reminiscences of Field.”

Mily Balakirev

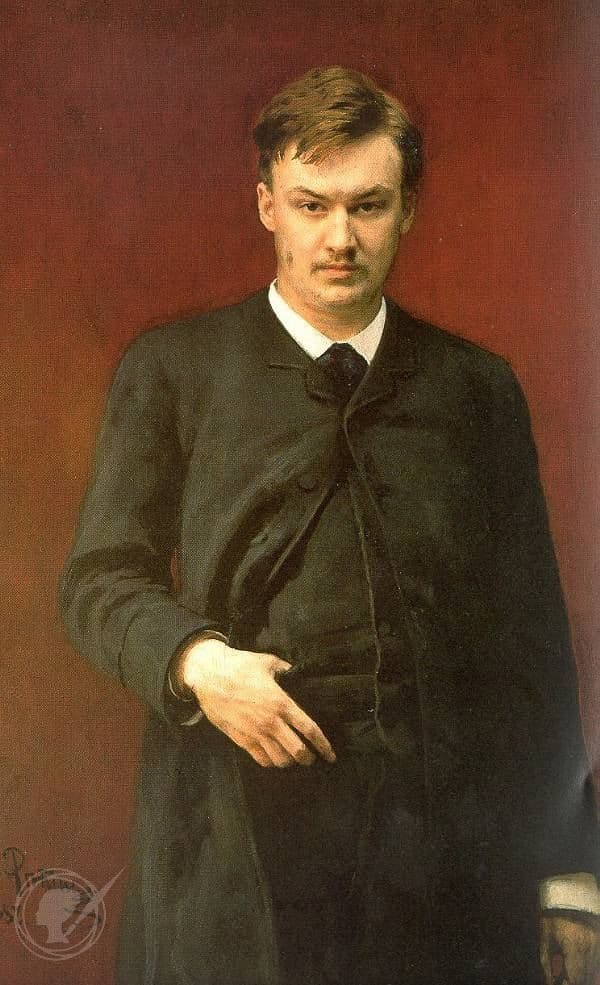

Both Tchaikovsky and Balakirev dedicated piano pieces to Dubuque, and it was Mily Balakirev, a member of the famed “The Five,” who discovered Alexander Glazunov. Glazunov had started taking piano lessons at the age of nine and fashioned his first compositions at the age of 11. Balakirev took his early compositions to Rimsky-Korsakov, and among his early works, we find two Nocturnes. These youthful works show clear musical attention to texture, clarity of melodic line and harmonic sumptuousness, all attributes going back to John Field.

Alexander Glazunov

The Rachmaninoff Connection

Nikolai Zverev

The Field student Alexander Dubuque also taught Nikolay Zverev, born into an aristocratic family, in 1833. Zverev studied mathematics and physics at Moscow State University, but concurrently, he also took lessons from Dubuque. Zverev inherited a large family fortune and moved to St Petersburg to become a civil servant. Unhappy with his career and urged on by Dubuque, he returned to Moscow to establish his private piano studio. When Nikolai Rubinstein invited him to teach at the Moscow Conservatory, he happily accepted.

Rachmaninoff was only 12 when he auditioned to become Zverev’s student. He was quickly accepted and entered the pianist’s home to receive private piano lessons. Rachmaninoff remembered, “I entered Zverev’s home with a heavy heart and foreboding, having heard tell of his severity and heavy hand, which he had no qualms of resorting to. Indeed, we were able to witness proof of this latter: Zverev had a temper and could launch himself at a person, fists flailing, or hurl some object at the offender. I myself had been the object of his fury on three or four occasions.”

Rachmaninoff continued, “but all other talk of his exacting and severe manner were false. This was a man of rare intellect, generosity and kindness. He commanded a great deal of respect among the best people of his time. Indeed, discipline entered my life.” In May 1886, Zverev took his students to Crimea, where Rachmaninoff continued his studies in hopes of being accepted into Anton Arensky’s class at the Moscow Conservatory.

Sergei Rachmaninoff

It was during this time that Rachmaninoff created his first composition, a now lost Etude in F-sharp Major. He also composed a group of pieces titled “Three Nocturnes,” works regarded as his first serious attempt at writing for the piano. The pieces are not entirely nocturnal in their approach, and they are certainly closer to Field than Chopin. The nocturnes were published only in 1949 without opus number, and while they lack maturity, they are full of suggestions of what was still to come.

First performed in 1892, Rachmaninoff’s C-sharp minor Prelude became his first real hit. In addition, Tchaikovsky tirelessly promoted Rachmaninoff’s talents, and the young composer was exceptionally successful in getting his early compositions into print. Rachmaninoff composed his “Morceaux de salon,” Op. 10, after graduation from the Moscow Conservatory in 1892. A “Nocturne in A minor” opens this collection of piano pieces, and like Field and Chopin, he concentrated on a framework of singing melodies supported by rich harmonies and elaborated by embellishments.

The Scriabin Connection

Georgy Konyus

With Alexander Scriabin we once again find the connection to John Field in the home of Nikolai Zverev. Scriabin had been able to play the piano with both hands by the time he was five, and he was able to reproduce the tunes he heard from passing organ grinders. He received his first formal music lessons from Georgy Konyus, who was not impressed. He writes, “He knew the scales and the tonalities, and with the weak sound of his little fingers which barely carried, he played to me, what exactly, I don’t remember, but it was accurate and satisfactory… he learned pieces quickly, but his performance, it should be remembered, as a result of the shortcomings of his physique, was always ethereal and monotonous.”

Because Scriabin could count on significant family connections, he was able to study with Taneyev, who prepared him for entry to the Moscow Conservatory. And in turn, Taneyev introduced Scriabin to Zverev. Zverev insisted that his students should live in his own house, and Scriabin “learnt not only French and German but also the manners of high society; he was shown great literature and how to drink vodka.”

Scriabin studied among a group of boys of similar age, and that included Rachmaninoff and Goldenweiser. During his study with Zverev, Scriabin performed Schumann’s “Papillons” in the Great Hall of the Charitable Society. That performance showed some obvious talent “despite some inaccuracy.” It was suggested that Scriabin became Zverev’s favourite student, but things changed when his young charge tried his hands at composition. When he dedicated a Nocturne in F-sharp minor to his teacher, later to be published as Op. 5, No. 1, Zverev put his foot down and told him to stop composing.

Alexander Scriabin

From his very beginnings, Scriabin loved the music of Chopin. It’s hardly surprising that we should find a couple of nocturnes in his oeuvre. Stephen Coombs writes, “The Two Nocturnes Op 5, written in 1890, have only the faintest suggestion of reflective ‘night music’ and could as easily have been titled ‘impromptus’ or ‘poems.’ Both pieces display an increased sensuousness and rhythmic freedom together with a more confident and daring use of harmony.”

Scriabin wrote only one more Nocturne, the second of his Two Pieces for Left Hand, Op. 9. Competing against the likes of Rachmaninoff, Hofmann and Lhévinne, Scriabin temporarily lost the full use of his right hand. Eager to prove his ability as a pianist, he turned the Nocturne into a particularly devilish technical exercise. As a pianist wrote, “with Scriabin, the nocturne breaks with the bel canto singing to which it was through John Field, historically linked.” Please join us next time when we take a closer look at the 10 most beautiful Nocturnes by Frédéric Chopin.

Saturday, July 20, 2024

Swan Lake - Tchaikovsky : A Classical Masterpiece

Friday, March 22, 2024

Composer Galina Ustvolskaya: The Shostakovich-Trained Iconoclast

By Emily E. Hogstadt, Interlude

Composer Galina Ustvolskaya (1919-2006) has been called “the lady with the hammer” and is known for her connection to Dmitri Shostakovich.

Galina Ustvolskaya and her dog

But she was so much more than this. She was also fiercely independent, staggeringly talented, and completely unafraid. She not only refused to fit in a musical mold but threw out that mold entirely.

Today, we’re taking a look at the life and times of Soviet composer Galina Ustvolskaya.

Ustvolskaya’s Childhood

Galina Ustvolskaya was born on 17 June 1919 in Petrograd to an unmusical family. Her father was a lawyer, and her mother was a teacher from impoverished nobility.

Her childhood was lonely and full of financial pressures.

“I would wear an old coat of my father’s (which was too long for me) and his muffler, which I gave to a young friend. I loved to give gifts, although we did not have anything to spare. Since childhood, I could not tolerate these kinds of pressures.”

Her desire for financial security would later impact her career choices.

She loved music deeply from an early age. When she was young, her parents took her to a performance of Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin, but the family had to leave when she started crying. “I want to be an orchestra,” she told them.

Time with Shostakovich

Ustvolskaya studied at a school for young people associated with the Leningrad Conservatory. In 1939, when she turned twenty, she joined Dmitri Shostakovich’s composition class. That year, she was the only woman in that class.

Shostakovich was intrigued by her and in awe of her talent. “I am convinced that the music of G. I. Ustvolskaya will achieve world fame and be valued by all who hold truth to be the essential element of music,” he wrote once. He also said, “It is not you who are under my influence, but I who am under yours.”

He valued her opinion so much that he asked for her feedback on his own compositions. He also used a theme from her clarinet trio in his fifth string quartet (from 1952) and his Suite on Verses of Michelangelo Buonarroti (from 1974, toward the very end of his life).

Ustvolskaya studied in his class twice – once from 1939 to 1941 and again from 1947 to 1948. That six-year break coincided with the war, as well as the devastating two-and-a-half-year siege of Leningrad.

A month into the siege of Leningrad, Shostakovich was evacuated to Moscow and Ustvolskaya to Tashkent, the current-day capital of Uzbekistan, along with others linked to the Conservatory. In 1943, she worked in a hospital in the city of Tikhvin, two hundred kilometers from St. Petersburg.

Galina Ustvolskaya

She later made it very clear that she was not keen on an association with Shostakovich. She called his music “dry and lifeless” and wrote to her publisher, “One thing remains as clear as day: a seemingly eminent figure such as Shostakovich, to me, is not eminent at all, on the contrary, he burdened my life and killed my best feelings.”

Her distaste for him may have been rooted in extra-musical reasons. She later claimed that Shostakovich proposed marriage to her, but she turned him down.

Later, she went even further: “There is no link whatsoever between my music and that of any other composer, living or dead,” she once proclaimed.

Ustvolskaya and Soviet Propaganda

From 1947 to 1977, she taught composition at the Leningrad Conservatory. She didn’t think of herself as a particularly talented professor – composition was her true calling – but teaching was a way to make a living.

In February 1948, a resolution went out from the Soviet government, accusing some composers of Formalism (i.e., failing to compose music that fully supported the state).

After this, she split her creative self into two parts. One composed propaganda pieces acceptable to Soviet leadership, while the other wrote secret avant-garde works that she knew might never be heard.

Writing music to please the authorities was soul-destroying, but she was apparently very good at it. Her tone poem Stepan Razin’s Dream opened the Leningrad Philharmonic’s 1949 season, to acclaim. She was even nominated for the Stalin Prize.

However, in 1962, she hit her limit. From that time on, she vowed to only write what she truly wanted to write, and she worked to destroy all traces of everything she ever wrote for political reasons.

Fortunately, later in the century, the Soviet Union started being easier on modernist composers, and allowing them to share some of their more controversial music. Ustvolskaya slowly began sharing some of the music she’d been keeping hidden.

Ustvolskaya’s Later Years

Galina Ustvolskaya

By the 1970s the Leningrad Union of Composers began presenting evenings of her music, and critics were impressed.

Her music has several distinguishing features, including extreme dynamics, unusual instrumentation, and brutal and relentless repetition.

The website Ustvolskaya.org writes, “Ustvolskaya’s music is unique, unlike anything else; it is exceedingly expressive, brave, austere, and full of tragic pathos achieved through the most modest of expressive means.”

Unfortunately, for years, hardly anybody outside the Soviet Union heard it. But in 1989 her work was performed at the Holland Festival, and it made a big impression on audiences.

She was living as a bit of a hermit by the 1990s, but she traveled to Amsterdam to watch performances of her work. Although she hated interviews, she agreed to one with journalist Thea Derk. But when the time for the interview came, she nearly backed out, and only agreed to partake after she was assured she could answer questions with monosyllables, without elaboration. (Luckily, Derk was able to get more than that out of her.)

She was asked how she liked the performance she’d heard. “Not very much,” she said bluntly. She elaborated: “The acoustics were not favourable, so that the piano didn’t come out properly, and the five double basses should have been placed more to the front. Moreover, the ensemble, recruited more or less ad hoc from members of the Concertgebouw orchestra, hadn’t as yet properly mastered the score, and the reciter wasn’t adequately amplified. But yesterday it was better and I hope it will again be better tonight.”

Ustvolskaya’s Death and Legacy

A perfectionist iconoclast to the end, Galina Ustvolskaya died in 2006 in St. Petersburg. She was eighty-seven years old.

In 1998 she gave a description of her life to an interviewer that serves as a kind of thesis statement about her music:

“The works written by me were often hidden for long periods. But then if they did not satisfy me, I destroyed them. I do not have drafts; I compose at the table, without an instrument. Everything is thought out with such care that it only needs to be written down. I’m always in my thoughts. I spend the nights thinking as well, and therefore do not have time to relax. Thoughts gnaw me. My world possesses me completely, and I understand everything in my own way. I hear, I see, and I act differently from others. I just live my lonely life.”

Friday, March 8, 2024

The Sting of a Bad Review — And Revenge!

by Janet Horvath , Interlude

Bad reviews hurt! Why else would we remember Word for Word our first bad review?

When I was a college student, I performed one of my first solos with an orchestra. I had just won the school wide concerto competition and I was chosen to perform Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. It was in a fabulous new concert hall in Ottawa, Canada. The review said, “… nice tone, iffy intonation…a talented but premature exponent of the Rococo Variations for Cello and Orchestra.”

Reviews can be nasty. Some of these are infamous. Perhaps you’ve heard worse? “Often dull and obscure…” wrote Leon Escudier about Bizet’s ever-popular opera Carmen. Regarding Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, The Harmonicon, an influential monthly journal of music, printed the following review, “… Frightful indeed, which puts the muscles and lungs of the band, and the patience of the audience to a severe trial…” \

Famed writer George Bernard Shaw was quoted as saying about the Brahms Requiem, “It is so execrable and ponderously dull…“

Another favorite composer, Rachmaninoff, didn’t escape the vindictive words of Cesar Cui. He wrote “… This music (Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 1) leaves an evil impression with it’s broken rhythms, obscurity and vagueness of form, meaningless repetition of the same short tricks…” And fellow Russian, Tchaikovsky?

“Tchaikovsky’s First Piano Concerto, like the first pancake, is a flop,” said Nicolai Soloviev.

Lexicon of Musical Invective

Between its hundreds of pages The Lexicon of Musical Invective, by Nicolas Slonimsky, first published in 1953, and later revised in 2000, is a collection of brutal outbursts. I suppose it is more entertaining to read a slam than a gushing review. None other than Peter Schickele of P.D.Q. Bach fame wrote the foreword to the book:

“It is a widely known fact—or, at least, a widely held belief—that negative criticism is more entertaining to read than enthusiastic endorsement. There is certainly no doubt that many critics write pans with an unbridled gusto that seems to be lacking in their (usually rarer) raves, and these critics often become more famous, or infamous, than their less caustic colleagues.

– From “Dangerous Minds”, Posted by Ron Kretsch

Klaus Tennstedt

One of our favorite conductors of all time was Klaus Tennstedt our principal guest conductor of the Minnesota Orchestra from 1979 to 1982. We just clicked! Everything we performed with him was magic. He was known for his brilliant interpretations of Mahler symphonies and we played many of those, but we also performed other works including Beethoven and a memorable performance of the New World Symphony of Antonin Dvořák. The interpretation was so deep and riveting that many of us were literally in tears on stage. It was one of those times that we ascended into the spheres making music that transcended boundaries. Sadly, the reviewer didn’t think so. We were aghast. The headline read:

“Is Klaus Tennstedt Losing His Touch?”

As perhaps you know, the slow movement has a memorable melody for the English horn, which was performed with great heart and soul by our young English horn player now a member of the Philadelphia Orchestra. The reviewer, with stunning ignorance, referred to the famous solo as an oboe solo — indicating to us that this person not only lacked discernment but also of basic knowledge of orchestral music.

Normally one has to take a bad review and swallow it! It’s a matter of taste, preference and perhaps experience of other performances. But here was a case of blatant ignorance.

The members of the orchestra decided to do something that we’ve never done before — not only did several of us write individual letters to the newspaper, we wrote a collective letter— a rebuttal, that was signed by virtually all the members of the orchestra, head lined:

Dvořák Conductor Didn’t Deserve Critic’s Caviling

“As members of the Minnesota orchestra, we wish to express our collective outrage at the criticism written by X. We strongly question the credibility of the XX in engaging a free-lance writer who knows so little about the subject matter. A cursory glance through the program notes would have revealed to X that the solo in the LARGO movement of Dvořák New World Symphony was not an oboe, as X stated, but an English horn…. unable to distinguish a great performance from a bad one….X stated Maestro Tennstedt had “nothing new to say about the New World Symphony…” criticizing the orchestra for including a “Warhorse” on the program that was capable of, “bringing down the house even with a high school orchestra… the last movement seemed to have nothing to say, but said it loudly…”

…The spontaneous ovation from the 2,200-plus members of the audience and the 82 members of the Minnesota Orchestra on the stage …constituted an eloquent testament to the depth of the performance and the profundity of Tennstedt’s interpretation…

The orchestra is forced to compete with the orchestras of Berlin, London, Boston, New York and Philadelphia (to name a few) for his time and talent and it is lamentable that the X prints insulting columns by a writer who not only displays a dearth of simple musical knowledge but also a total lack of critical acumen… Klaus Tennstedt’s knowledge and genius are not in question. However the critical perceptiveness of X and the editorial integrity of XX most certainly are.

The reviewer was fired. Bad reviews may be part of the business but the next time you are rejected, passed on or criticized, remember our sweet revenge!

Friday, March 1, 2024

Tchaikovsky for Beginners: 12 Pieces to Make You Love Tchaikovsky

by Emily E. Hogstad February 26th, 2024

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born on 7 May 1840 in Votkinsk, a town almost eight hundred miles east of Moscow.

Nowadays he is remembered as music’s quintessential Russian Romantic, and a forebear to giants like Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, and Shostakovich.

Pyotr Il’ych Tchaikovsky

Today we’re looking at twelve pieces spanning the length of Tchaikovsky’s composing career. Before we jump in, here are some things you should know about him.

- Tchaikovsky wrote music in an era of nationalism:

During his lifetime, artists of all kinds were inspired by their national identities.

Tchaikovsky often found himself caught up in debates about whether Russian composers should focus on creating uniquely Russian music or copying a more Western European style (he preferred the idea of striking a balance between both).

That said, the Russian vocabulary of his work is unmistakable, and it influenced future Russian and Soviet composers for generations to come. - Tchaikovsky was gay. He married in 1877, but it was the most traumatic experience of his life. Six weeks after the wedding, he fled the country to recover. He and his wife never reconciled, but they also never divorced.

- Tchaikovsky suffered from crippling self-doubt. He was enamored by his work one moment, then repulsed by it the next. This emotional seesaw is a hallmark of his works, as well.

- Tchaikovsky was able to write much of his music due to the financial aid of a wealthy woman named Nadezhda von Meck, who pledged to support him…just as long as they never met in person. This unusual arrangement worked well for both parties, and the letters they exchanged became important emotional outlets for each of them.

- Tchaikovsky died of cholera in 1893, supposedly after drinking a glass of contaminated unboiled water, but conspiracy theories have surrounded his death for generations. Some people believe it was suicide or forced suicide, perhaps due to his homosexuality.

Tchaikovsky tomb at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery

If that peek at Tchaikovsky’s dramatic life intrigues you, keep reading. Here are twelve pieces that will make you fall in love with Tchaikovsky:

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1874) Tchaikovsky’s

has become one of the most popular works for piano and orchestra ever written, but originally, it was criticized.

A 34-year-old Tchaikovsky brought the score to pianist Nikolai Rubinstein as soon as he finished it, looking for feedback. Rubinstein was brutal in his assessment: he hated it.

Tchaikovsky wrote later, “I need and shall always need friendly criticism, but there was nothing resembling friendly criticism. It was indiscriminate, determined censure, delivered in such a way as to wound me to the quick.”

But when the work was premiered in Boston in 1875, the audience loved it. They continue to love it to this day.

You can hear elements in this work that read as Russian, especially the lush sweeping string passages and folk dance rhythms.

Swan Lake (1875-1876)

We don’t know exactly where the story of Swan Lake came from, although it’s possible that Russian folklore was an inspiration.

In this ballet, a prince is told by his mother that he must marry as soon as possible and that a slate of options will be presented to him at a ball the following night. A flock of swans flies overhead. To distract himself from his imminent engagement, the prince embarks on a hunt.

Swan Lake ballet performance

© PortsmouthNH.com

One swan transforms into a beautiful woman named Odette. A sorcerer has enchanted her, and the only way she can return to human form is if someone who has never loved before promises to love her forever. She is then turned back into a swan.

The following night at the ball, the sorcerer arrives with a woman who looks just like Odette. Unfortunately, the sorcerer has transformed his own daughter to look like Odette, and the real Odette is still stuck by the lake. Obliviously, the prince falls in love with the fake Odette.

But when the prince discovers the girl’s true identity, he rushes to the real Odette and apologizes. Unable to break the spell, the two decide to die together. They reunite after death.

A variety of alternative endings exist, too, but the story is always secondary to Tchaikovsky’s dramatic music.

It’s easy to see why Tchaikovsky poured his heart and soul into this project. It touches on his love of dance and drama, tapping into an unrestrainedly emotional Russian style of writing. It also reflects the despair of a man being forced to marry, and the tragedy present in doomed love.

Slavonic March (Marche slave) (1876)

In 1876, an organization called the Russian Musical Society commissioned a piece from Tchaikovsky to be played at a benefit concert for wounded Serbian veterans.

At the time, Serbia and the Ottoman Empire were fighting the Serbian-Ottoman wars, in which Serbia was seeking its independence from the Empire. Russia had allied itself with Serbia in the struggle. So this work is a bit of musical propaganda.

Tchaikovsky uses Serbian folk songs in this work, as well as the melody from the Russian imperial anthem God Save the Tsar. He intertwines these melodies with a militaristic musical language that’s heavy on brass, piccolo, and percussion.

Even though the military conflict it was written about is long over, the work remains popular for its heart-on-sleeve bombast.

Violin Concerto (1878)

Tchaikovsky married a pianist named Antonina Miliukova on 18 July 1877. His crush, violinist Yosif Kotek, was one of the witnesses. Six weeks later, Tchaikovsky fled the country alone to come to terms with his disastrous decision.

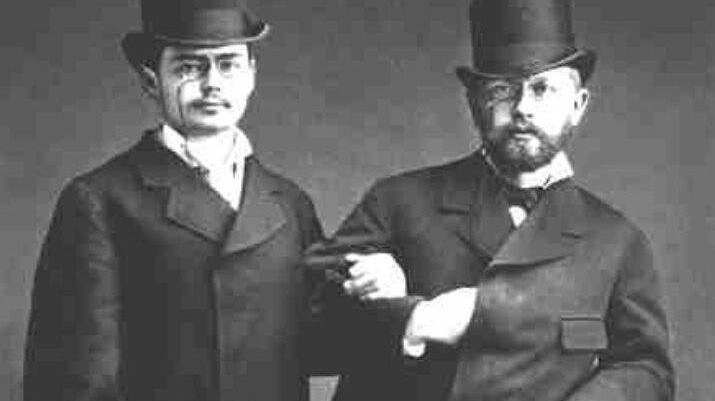

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Yosif Kotek

In March 1878, he ended up at his patroness’s Swiss estate. Kotek came to visit, and the two struck up a productive creative partnership. With Kotek’s help, inspiration, and feedback, Tchaikovsky wrote his violin concerto in under a month. Today it is one of the most popular violin concertos in the repertoire, and it’s bursting with longing, regret, and joy.

Things didn’t end well between Tchaikovsky and Kotek. Any attraction they had for one another quickly cooled, especially after Kotek began seducing a string of women. But the violin concerto remains as a monument to their deep affection for one another.

Serenade for Strings (1880)

The patroness whose Swiss estate Tchaikovsky had fled to was none other than Nadezhda von Meck.

In 1877, the same year as his wedding, she began sending Tchaikovsky 6000 rubles a month, a hugely generous income that enabled him to quit teaching and focus solely on composition.

Nadezhda von Meck © en.tchaikovsky-research.net

His connection with her helped kick off a new era in his creative life. The Serenade for Strings is one of the pieces from early in their creative partnership.

Tchaikovsky wrote this serenade as a kind of antidote, because he was burnt out from composing another work that he feared was artistically worthless…

1812 Overture (1880)

The work that Tchaikovsky feared was artistically worthless was the 1812 Overture, a work that has become among Tchaikovsky’s most popular.

The overture was commissioned to celebrate the completion of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in St. Petersburg, a monument that had been started generations earlier, after Napoleon’s ill-fated attempt to overtake Russia.

The historical event was massive and the cathedral was massive, so the overture had to be massive, too. Tchaikovsky wrote parts for a large orchestra with a huge percussion section, a brass band, pealing church bells, and even cannons, which were supposed to be set off by electric switch.

The scale of the premiere deflated after the assassination of the tzar in 1881. It took until the 1950s for a recording to be made that actually included cannon fire.

Capriccio Italienne (1880)

One of the destinations that Tchaikovsky escaped to while avoiding his new wife was Italy. Tchaikovsky was enchanted by Italy. He wrote to Nadezhda von Meck:

“I have already completed the sketches for an Italian fantasia on folk tunes for which I believe a good fortune may be predicted. It will be effective, thanks to the delightful tunes which I have succeeded in assembling partly from anthologies, partly from my own ears in the streets.”

Even though the purportedly Italian-inspired Capriccio is also very Russian, it works well, anyway. It remains a moving musical portrait of what Tchaikovsky saw as he was recovering and coming to terms with the trauma of his marriage.

Romeo and Juliet Overture (1880)

Another coping mechanism that Tchaikovsky used during this time was reworking music from his past.

In the late 1860s, when he was a young music professor in St. Petersburg, Tchaikovsky fell in love with a magnetic singer named Désirée Artôt. Since Artôt ended up being the only woman in his entire life who Tchaikovsky felt this way about, some people speculate that he may have been in love more with her singing than with her as a person.

Désirée Artôt

The two discussed marriage, but she ultimately married another man…possibly because she heard about Tchaikovsky’s same-sex attraction.

Shattered by the rejection, Tchaikovsky wrote a symphonic poem based on the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet. He struggled with mixed feedback from renowned composer Mily Balakirev. One version was premiered in 1870, and a second in 1872, but neither one stuck.

Fortunately, during his burst of creative productivity in 1880, he finally figured out what he wanted to say with the piece, and reworked it a third time, to great effect.

The love theme was adored by audiences, and it remains cultural shorthand for love, even today.

Orchestral Suite No. 4 in G major “Mozartiana” (1887) Play

Mozart had always been Tchaikovsky’s favorite composer. In 1887, on the centenary of the premiere of Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni, Tchaikovsky came out with this orchestral suite to celebrate his hero.

This work is unusual in Tchaikovsky’s output in that it is based on Mozart piano pieces (as well as a slightly treacly reworking of a passage from his Requiem).

It’s fascinating to hear how this most Romantic of Russian composers treats the delicate work of Mozart, the Classical era’s poster child. It reveals a new side to Tchaikovsky’s interests and musical personality that isn’t often seen.

Symphony No. 5 (1888)

In 1888, Tchaikovsky wrote a note to himself: “Introduction. Complete resignation before Fate – or, what is the same thing, the inscrutable designs of Providence.”

This idea of a symphony exploring the idea of unalterable fate – with all of the darkness, joy, and inevitability that such an idea implies – became a part of his fifth symphony, which opens with a theme that has come to be known as the “fate” theme, and which recurs throughout the work.

He updated von Meck: “I shall work my hardest. I am exceedingly anxious to prove to myself, as to others, that I am not played out as a composer. Have I told you that I intend to write a symphony? The beginning was difficult, but now inspiration seems to have come. We shall see…”

He finished it in a few months, but the premiere was unsuccessful. He updated von Meck, “Having played my Symphony twice in Petersburg and once in Prague, I have come to the conclusion that it is a failure. There is something repellent in it, some over-exaggerated color, some insincerity of fabrication which the public instinctively recognizes.”

However, within a matter of months, having returned to it and performed it again, he changed his mind yet again, writing to his nephew, “I have started to love it again. My earlier judgment was undeservedly harsh.”

Whether you love it or hate its over-the-top emotion, take solace in the fact that at some point, Tchaikovsky agreed with you!

The Nutcracker (1892)

For The Nutcracker, which would turn out to be his last ballet, Tchaikovsky partnered with legendary choreographer Marius Petipa.

Their partnership became extremely granular. Petipa gave measure-by-measure instructions about what he was envisioning for the dance, and Tchaikovsky delivered. Despite this, the colorful score feels incredibly free and organic.

The initial response to The Nutcracker was lukewarm, but future generations came to treasure it. After dancer George Balanchine choreographed a version in New York in the 1950s, it became established as a December holiday tradition, especially in America.

The Nutcracker has become so popular that it has single-handedly helped keep many ballet companies afloat in financially difficult times. Tchaikovsky would no doubt be pleased!

Symphony No. 6 (1893)

Tchaikovsky began the composition of the sixth symphony by creating notes…and then ripping them up.

But he kept trying. In 1893, he wrote to his nephew, “I am now wholly occupied with the new work … and it is hard for me to tear myself away from it. I believe it comes into being as the best of my works.”

What resulted was his darkest music yet, exploring themes of loss and mortality. Notably, it ends on a quiet, tragic note, instead of the much more common flurry of triumph.

Composing the work seems to have excised dark feelings for Tchaikovsky. His brother wrote later, “I had not seen him so bright for a long time past.”

The symphony was premiered in late October 1893. On the Wednesday after its premiere, he went to a restaurant and supposedly drank unboiled water. On Thursday, he began showing symptoms of cholera. On Monday, he was dead.

Tchaikovsky on his death bed

For obvious reasons, the sixth symphony is the most mythologized piece in Tchaikovsky’s entire output. It is difficult to listen to it and not think of the tragic fate that befell its composer a few days after its premiere. This juxtaposition has led to all sorts of conspiracy theories.

Conclusion

There are many reasons why Tchaikovsky is one of the most beloved composers in classical music history.

His music is accessible and affecting. He knew how to spin a melody and how to orchestrate, and he never got caught up in academic arguments at the expense of the music. For him, expressing emotion was always the most important thing, and audiences through the generations have responded to that.

Add in the struggles he faced with depression and self-doubt, and the lifelong struggle of hiding his homosexuality and never being able to be in an open relationship with a man, and he becomes a relatable – albeit tragic – figure for many people.

One thing is clear. As long as orchestral music is played, it seems likely that audiences will be hearing and loving Tchaikovsky.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)