Gershwin’s Forgotten Rhapsody

We all know George Gershwin (1898–1937) and his Rhapsody in Blue, his 1924 composition that, beginning with an extended clarinet glissando, firmly issued jazz into the world of classical music. The work was commissioned by bandleader Paul Whiteman and received its premiere at Aeolian Hall in New York with George Gershwin at the piano. Gershwin wrote it, Whiteman’s arranger Ferde Grofé orchestrated it, and history was made.

Carl Van Vechten: George Gershwin, 1937

It was written in the 5 weeks between the announcement of the commission (small detail: Gershwin had already declined to do it!) and the concert on February 12, 1924. Gershwin fleshed most of it out on a train trip between New York on Boston, where the ‘rattle-ty bang’ of the train inspired him and by the end of the journey, he had the structure in place. He started formal composition on 7 January and passed the score to Grofé on 4 February, a mere 8 days before the concert.

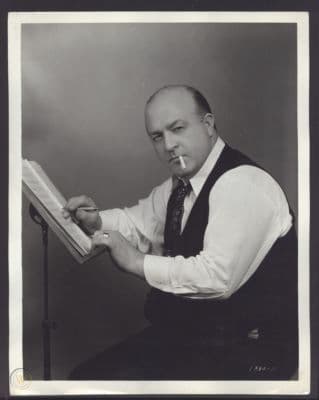

Paul Whiteman

Ferde Grofé, 1935

Billed as “’An Experiment in Modern Music”, Whiteman’s classical/jazz concert had 26 different pieces on the programme. Gershwin’s piece was no. 25. The earlier works hadn’t always been successfully received and the ventilation system in the hall wasn’t working. Gershwin took his place at the piano and with that unmistakable wail on the clarinet, the fleeing audience was stopped in its tracks and a new era in classical music was born.

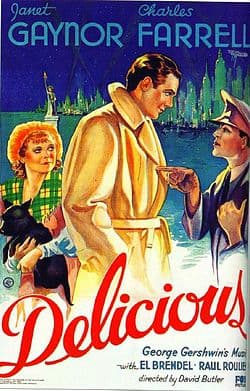

What’s been largely overlooked, however, is that Gershwin wrote another jazz concerto, the Second Rhapsody. In 1931, Gershwin was in Hollywood, writing music for the movies, when he was asked for a six-minute instrumental interlude for the movie Delicious, an early colour film set in Manhattan involving a newly arrived Scottish girl who falls in with a miscellaneous group of immigrant musicians.

“Delicious” film poster

Gershwin wrote more music than Fox Studios needed and nearly half of his music ended up on the editing room floor, but Gershwin took it to the recording studio on its own. It was given its concert premiere in January 1932 by the Boston Symphony Orchestra under Serge Koussevitzky, with Gershwin as soloist.

The most common version heard for the first 50 years after its composition was a re-orchestration done by Robert McBride, as commissioned by the music editor at Gershwin’s publisher. In this edition, Gershwin’s original vision has been simplified, voices reassigned (for example, the string quartet portion of the adagio was rescored for violin, clarinet, oboe, and cello), and former solo lines were now doubled. Also, 8 measures cut by Gershwin were added back in by McBride. The soloist is Gershwin’s friend, Oscar Levant (1906–1972).

Oscar Levant in An American in Paris, 1951

Various versions ended up in circulation – some cut down by Gershwin, some cut down by other editors – and it’s only since 1985, when conductor Michael Tilson Thomas started researching the original version that Gershwin wrote, that we start to approach the original. MTT recorded what he found with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1985.

The motifs are pure New York in the 1930s: the hammering motif at the beginning depicts riveters at work on the city’s skyscrapers, remember that the world’s tallest building, the Empire State Building, was begun in 1930 and completed in 1931, dominating the New York skyline until the World Trade Center towers eclipsed it in 1970.

Empire State Building, 2012

Riveters at work

This is what gave the work one of its earliest names: Rhapsody in Rivets. It was next given the title of New York Rhapsody, then Manhattan Rhapsody before Second Rhapsody came to the fore. In addition to the rivets, other elements of the city come in as well, with Latin rhythms providing a driving force along with the rivets. Jazz and blues also have their place. This performance by Freddy Kempf says it’s ‘in the original 1931 orchestration by the composer’.

Some blame the excessive percussive rhythms for the work’s lack of popularity, others for the lack of a definitive score that preserves Gershwin’s original ideas. The Gershwin family, as part of a larger project to create scholarly editions of Gershwin’s music in conjunction with the Library of Congress and the University of Michigan, is working on a definitive edition of the work that should help it get back onto the concert stage.

No comments:

Post a Comment