It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Thursday, October 2, 2025

Madame Butterfly by Puccini - Love Duet (Opera Movie, 1995 - subtitled)

Thursday, May 22, 2025

Friday, December 27, 2024

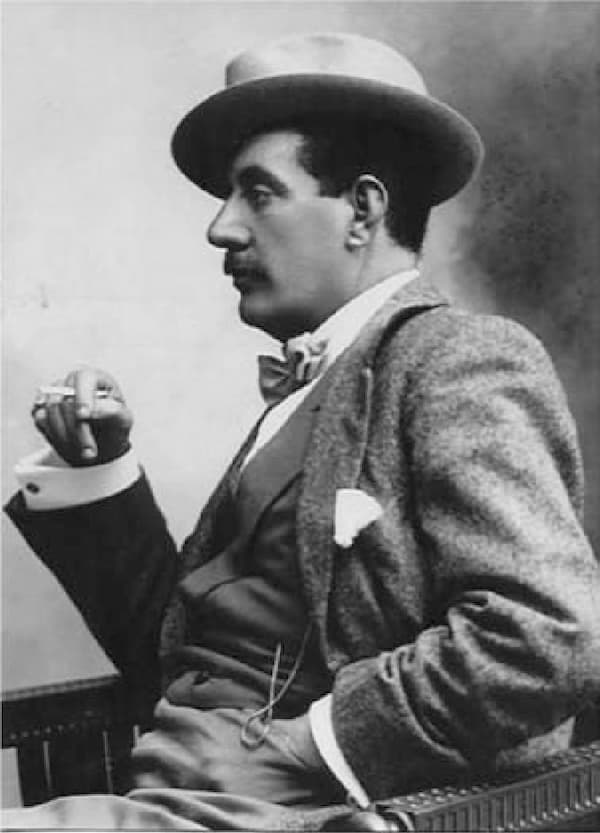

Giacomo Puccini

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Giacomo Puccini

One of the most important and influential composers in the history of opera, Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) produced works of emotional depth, melodic beauty, and rich orchestration. Bringing a new level of realism and expressiveness to the genre, Puccini’s masterworks are famous for their vivid characterisations and the ability to convey complex human emotions.

As Michele Girardi writes, “Puccini revolutionised Italian opera by mastering the orchestra and introducing bold harmonic progressions, aligning with European trends rather than traditional Italian styles. His innovative blending of lyrical vocal lines with intricate orchestral textures produced tender moments of sublime vocalism nestled within the passionate “verismo” style.” On the occasion of Puccini’s birthday on 22 December, let us explore this revolutionary composer through his music.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Nessun Dorma”

Early Days

Giacomo Puccini

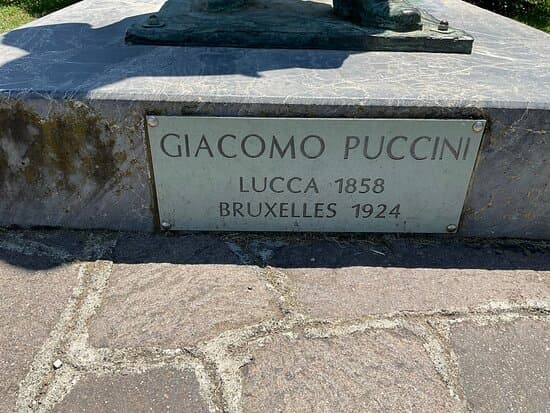

Giacomo Puccini, born on December 22, 1858, in Lucca, Italy, was part of a prominent musical family that had held the position of maestro di cappella for over a century. His father, Michele, was a church organist and choirmaster who died when Puccini was only six, marking a significant turning point in his life. Despite early academic struggles, including a reputation for being a bit of a troublemaker, Puccini pursued music under his uncle and later at the Pacini School of Music, eventually earning a diploma in 1880.

Giacomo Puccini continued his studies at the Milan Conservatory, composing his first Mass and submitting the Capriccio Sinfonico, a work that earned him recognition, as his graduation project. His first opera, Le Villi, dates from 1884 and was the result of a collaboration with poet Ferdinando Fontana. Puccini continued to revise and expand the opera, and the final version was issued in 1889. In terms of harmonic delicacy and dramatic orchestration, it laid the foundation for his future opera career.

Giacomo Puccini: Le Villi, “Torna ai felici di”

Edgar and Beyond

Giacomo Puccini’s Edgar

Based on a poem by Alfred de Musset, Puccini’s next opera Edgar premiered at La Scala in 1889. Lacking dramatic cohesion and despite a number of revisions, the work was poorly received and ultimately was Puccini’s only true failure. However, Puccini clearly learned his lesson and Manon Lescaut of 1893 became a great success. The libretto underwent a rather complicated development until librettist Luigi Illica strengthened the score and improved the drama.

A scholar writes, “drawing from Wagner’s idea of the leitmotif and combining it with the Italian dramma in musica, Puccini advanced the integration of music and drama.” In other words, Puccini uses recurring themes to represent the emotions and destinies of his characters, as Manon’s theme is repeated throughout the opera, symbolising the heroin’s fate and relationship with her lover. According to scholars, “Puccini’s skilful use of symphonic structures and thematic relationships in Manon Lescaut pushed the boundaries of the operatic genre.”

Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut, “Sola perduta abbandonata”

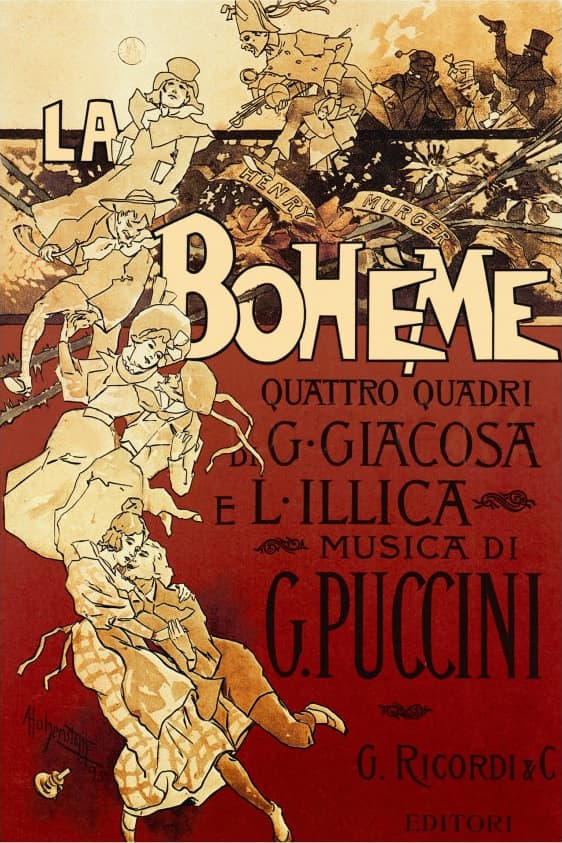

Realism and La Bohème

Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème

La Bohème is based on Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème, a collection of loosely related stories all set in the Latin Quarters of Paris. Puccini collaborated with librettists Illica and Giacosa to create a seamless integration of text and music. In fact, a good many people consider it Puccini’s finest libretto. La Bohème, premiered in 1896, stands out for its blend of realism and poetry. Puccini moved beyond traditional operatic forms by using continuous music to reflect everyday life.

Puccini uses lyrical melodies, varied orchestration, and recurring motifs to deepen emotional and narrative impact. The opera’s realism is highlighted in the second scene with dynamic and fast-paced action as cinematic events bring the environment to life. A scholar writes, “a cyclical structure elevates the personal tragedy to a universal level, leaving the sorrow fixed in the timeless realm of art.” In Bohème, Puccini was able to achieve that perfect balance of realism and romanticism, of comedy and pathos, which makes it one of the most satisfying works in the operatic repertory.

Giacomo Puccini: La Bohème, “Quando m’en vo”

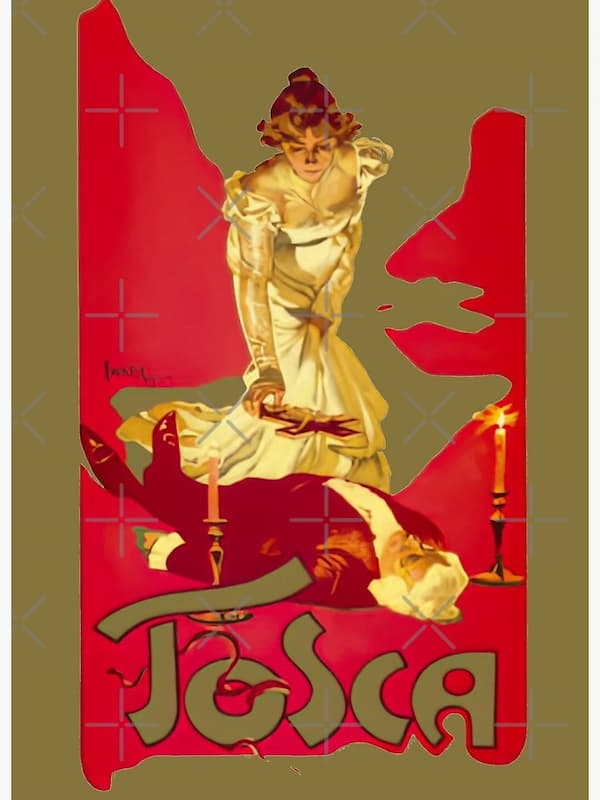

Realism and Tosca

Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca poster

In Tosca, Puccini focused on personal conflicts rather than social status. The story pits the passionate opera singer Floria Tosca and the painter Mario Cavaradossi against the heinous chief of police, Baron Scarpia. The opera explores the fleeting nature of Tosca and Cavaradossi’s love against a backdrop of political and religious conflict. The operatic realism is grounded in historical details and in the choice of three famous Roman locations.

Tosca is the most Wagnerian of Puccini’s operas. It musically relies on a web of musical leitmotivs, providing glimpses of a character’s thoughts and emotional state. Puccini’s musical language, featuring diatonic melodies and successions of unrelated chords, perfectly complements the theatrical and dramatic aspects of the work, and his blending of dramatic realism with modern operatic technique “marked his entry into the 20th century.”

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca, “Vissi d’arte”

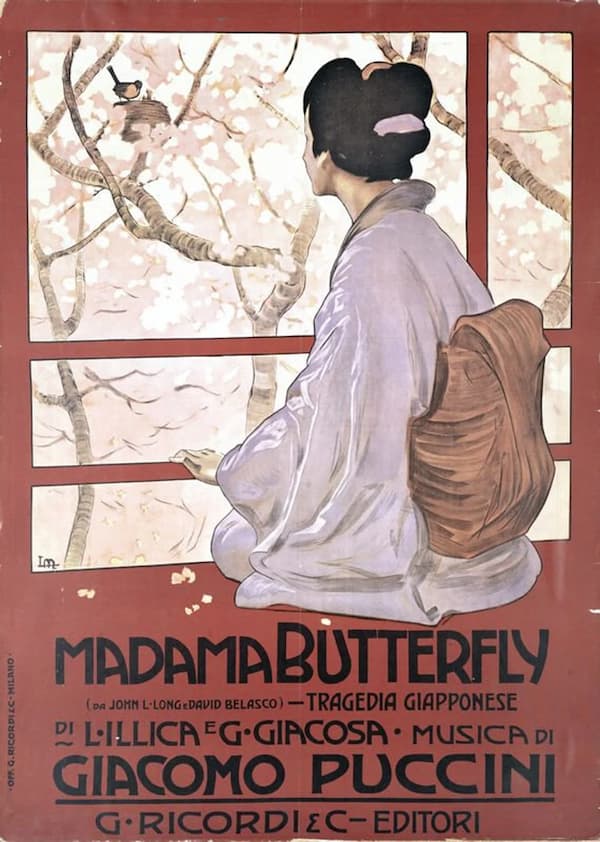

The Exotic

Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly

Puccini saw the one-act play Madame Butterfly, written and produced by the American playwright David Belasco in London in 1900. Drawn to the emotional depth of the story, Puccini crafted a powerful exploration of love, delusion, and tragedy. In terms of music, Puccini was striving for a sense of Japanese authenticity, engaging in exhaustive research to find, or at least approximate that sense of musical identity.

In all, Puccini revised his Butterfly for a grand total of five times, with the 1907 version considered to be his final say. In Butterfly, Puccini found a wonderful balance between the sentimental and the overwhelming, as moments of great delicacy alternate with emotional outbursts. The conflict is both personal and cultural, and through his unforgettable melodies, not to mention his sophisticated style of orchestration that cleverly aligns specific instrumental groups and orchestral timbres to match distinct dramatic moments, Puccini’s timeless creation will continue to resonate on a variety of psychological and cognitive levels.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Vogliatemi bene”

Evolution

Giacomo Puccini’s La fanciulla del West poster

Puccini called his opera La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the West) his “greatest work.” The work had been seven years in the making and originated during a period of severe family strife. As his long-time collaborator Luigi Illica had died in 1906, Puccini struggled to find a replacement. Puccini was also looking for new directions as he had grown disillusioned with conventional opera genres. A scholar writes, “La fanciulla departs from his earlier operas’ reliance on strict realism and instead delves into more symbolic, emotional expression.”

The opera’s dramatic complexity, innovative use of orchestration, and its departure from rigid realism show a composer at the height of his powers, experimenting with new ways to connect with modern audiences. Clearly, he was not able to please everyone as a good many commentators suggested that Puccini’s music represented a debasement and cheapening of pure Italian values. And his considerable fame abroad was seen as proof that the composer had “wilfully sacrificed national character for cheap commercial exploitation.”

Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West, “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano”

Unity

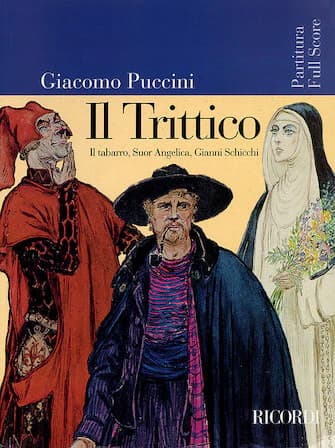

Giacomo Puccini’s Il Trittico recording cover

After the success of La fanciulla and La Rondine, Puccini eagerly explored this convergence of theatre and music. He began work on a one-act opera in 1913, however, he ended up with a collection of three one-act operas entitled Il Trittico. Comprising Il Tabarro (The Cloak), Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica), and Gianni Schicchi, Puccini attempted to draw together three different operatic genres, the dramatic, sentimental and comic, respectively, in a single project.

In Il trittico, Puccini shows himself to be the undisputed master of musical-dramatic continuity. This continuity becomes apparent within both the constraints of each singular one-act opera, as well as spanning a whole evening of operatic entertainment. This fascinating exploration of contrasting genres continues to be “one of the most innovative and complex works in the operatic canon.”

Giacomo Puccini: Gianni Schicchi, “O mio babbino caro”

Final Effort

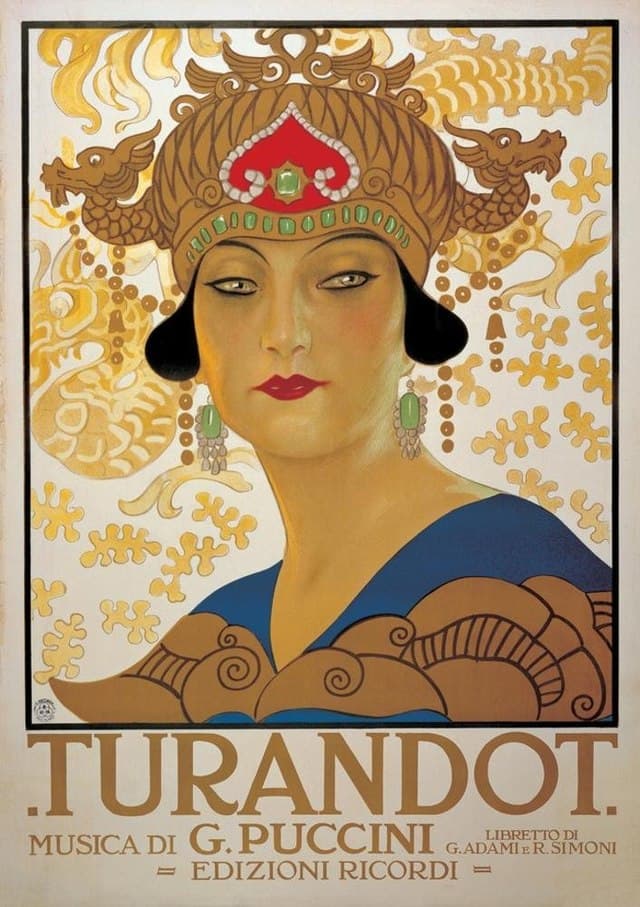

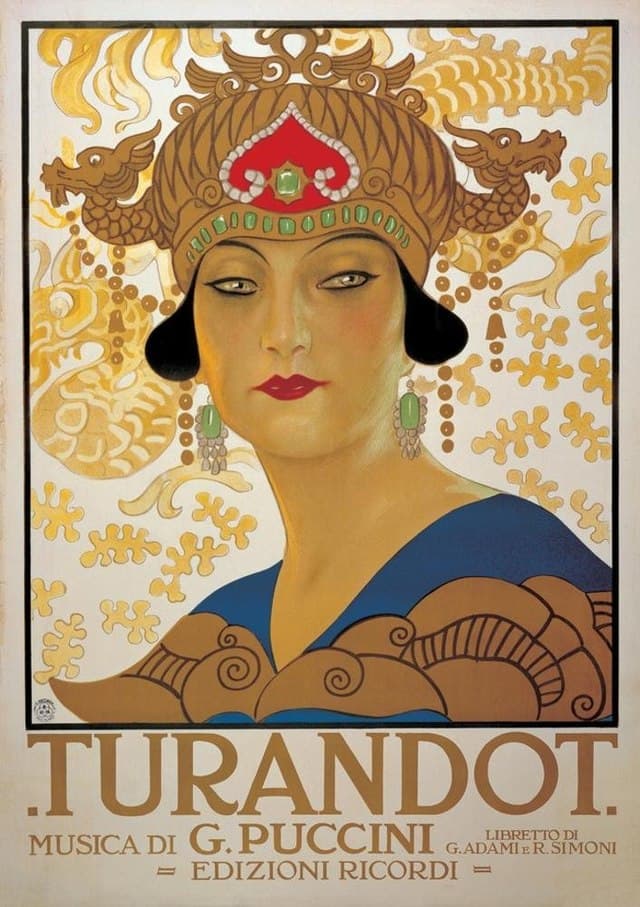

Poster of Turandot‘s performance

Puccini began working on his opera Turandot in the winter of 1919/20, urging his librettists Adami and Simoni to supply him with an Italian translation of Schiller’s adaptation of Carlo Gozzi’s play. Depicting distant lands and customs was a centuries-old musical tradition and Puccini demanded to “find a Chinese element to enrich the drama and relieve the artificiality of it, and to make use of Chinese syllables to give it a Chinese flavour.”

Puccini, once again, looked for a sense of authenticity in this musical characterisation. He visited a former diplomat in China, who owned a music box of genuine Chinese tunes. Three melodies from this music box ultimately found their way into the operatic score. Puccini left his last and most ambitious project unfinished, and Turandot has been described as “the last great Italian opera.”

However, much of the work is not Italian, as it draws on other cultures. Yet, it is in no way authentically Chinese either. A scholar writes, “it is a Western projection of the East, rife with contradictions, distortions, and racial stereotypes, and yet is also one of the most exhilarating and impressive works ever to take the operatic stage.”

Friday, November 29, 2024

On This Day 29 November: Giacomo Puccini Died

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Giacomo Puccini in Torre del Lago, where he lived for thirty years

Like his colleagues before, the physician discovered nothing suspicious beyond a slight inflammation deep down the throat. He advised Puccini to take a complete rest, abstain from smoking and come back in fourteen days. While his family was clearly relieved, Puccini knew that things weren’t right.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Tu che di gel sei cinta”

Unbeknownst to his family, Puccini consulted yet another specialist in Florence who diagnosed a “walnut-sized advanced extrinsic cancer of the supraglottis.” Tonio refused to accept the diagnosis but was told in no uncertain terms that his father was suffering from cancer of the throat in so advanced a stage that an operation would be futile. After consulting a number of eminent specialists, it was suggested that treatment by X-ray “was the only method likely to arrest the rapid progress of the disease.”

Puccini in 1924

As this kind of treatment was in its infancy, there were only two clinics in all of Europe where the method had been tried out with some success. Puccini decided to consult Dr. Ledoux in Brussels, and he wrote to his librettist Adami on 22 October 1924, “I am leaving soon… Will they operate on me? Shall I be cured? Or condemned to death? I cannot go on like this any longer. And then there is Turandot… Puccini departed for Brussels on 4 November 1924, taking with him sketches for the love duet and the finale of the last act, thirty-six pages in all.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Nessun dorma”

The first part of the experimental treatment saw Dr. Ledoux place a collar containing radium around Puccini’s neck. Puccini reports, “I am crucified like Christ! External X-ray treatment at present—then crystal needles into my neck and a hole in order to breathe… What a calamity! God help me. It will be a long treatment, six weeks, and terrible.”

Poster of Turandot‘s performance

During his initial treatment stage, Puccini was not confined to bed but was allowed to leave the clinic. He went to see a performance of Butterfly at the Theatre de la Monnaie, and his clinical condition improved. Puccini visited the local markets and went out for luncheons, and he started smoking again. The second part of the treatment commenced on 24 November, when seven needles were inserted into the tumor in an operation that lasted three hours and forty minutes. Although Puccini suffered agonizing pain, Dr. Ledoux was apparently satisfied that Puccini would pull through.

Memorial plate of Puccini

Unexpectedly, however, Puccini collapsed in the evening of 28 November and he died of heart failure at 4 am on 29 November 1924. A biographer writes, “Dr. Ledoux was so shattered by this sudden turn of events that, driving home in his car afterward, he is said to have fatally injured a woman pedestrian.”

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Del primo pianto si, straniero”

When news of Puccini’s death reached Rome, a performance of La Boheme was stopped, and the orchestra spontaneously played Chopin’s “Funeral March.” The funeral ceremony took place on 1 December in Brussels, and mourners silently lined the street from the clinic to the Church of Ste Marie. When Mme Laure Berge sang Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” a wave of emotion “rippled through the crowd outside the church as the public wanted to share their sorrow for the loss of a famous and very loved Maestro.”

Statue of Giacomo Puccini in Lucca, Italy

Puccini’s body was taken to Milan two days later. Toscanini and the Scala orchestra played the Requiem music from Edgar. Amid torrential rain Puccini’s mortal remains were then conveyed in a solemn procession to the Cimitero Monumentale for provisional burial in Toscanini’s family tomb. On the day of the second anniversary of his death, the coffin was brought to Torre and placed in “the mausoleum, which Tonio had erected in the villa by the lake. Pietro Mascagni spoke the funeral oration, and the conductor Bavagnoli and an orchestra performed music from Puccini’s operas. As for Turandot, Franco Alfano was commissioned to complete the score, a task that took him roughly six months.

Monday, November 18, 2024

Puccini - Madama Butterfly, "Vogliatemi bene"

/ wocomo

The performers are:

Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden

Giuseppe Sinopoli - conductor

Angela Gheorghiù - soloist

Roberto Alagna - soloist

Repertoire:

Giacomo Puccini - Madama Butterfly, "Vogliatemi bene"

© 1999, Licensed by Digital Classics Distribution

/ wocomo

The performers are:

Sächsische Staatskapelle Dresden

Giuseppe Sinopoli - conductor

Angela Gheorghiù - soloist

Roberto Alagna - soloist

Repertoire:

Giacomo Puccini - Madama Butterfly, "Vogliatemi bene"

© 1999, Licensed by Digital Classics DistributionTuesday, October 15, 2024

Glorious operatic singing in ‘Progetto Puccini’

Glorious operatic singing marked the culminating concert of “Progetto Puccini” (Puccini Project), thrilling the opera lovers who came in droves to the Metropolitan Manila Theater to watch recently.

Participants of the four-day master classes on operatic acting and singing took turns singing arias in the first half of the concert, which preceded the more challenging staging of “Scenes and Arias” from Giacomo Puccini’s well-loved opera, “La Boheme.”

The master classes were held daily at the Met on Oct. 1 to Oct. 4, conducted by the celebrated tenor turned conductor Fabio Armiliato; Mariano Panico, a musical director and voice teacher; and Lorena Zaccaria as diction coach. They took turns teaching vocal technique and production, diction, interpretation and stagecraft. A mini recital in the afternoon capped what had been done and learned for the day.

Friday, August 16, 2024

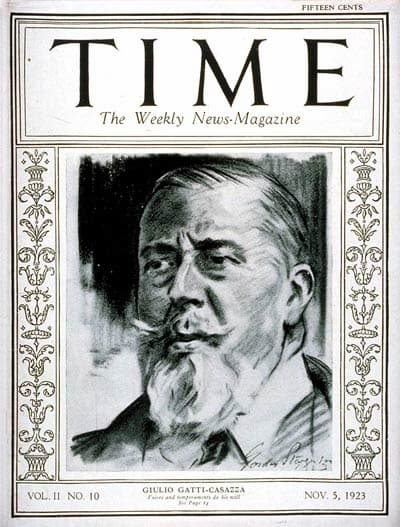

Movers and Shakers: Giulio Gatti-Casazza (1869-1940)

by Georg Predota

He single-handedly revolutionized the world of opera by applying an unprecedented entrepreneurial philosophy to arts management. Giulio Gatti-Casazza managed La Scala in Milan for a decade, and he also served as the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera of New York for a record 27 seasons! His ideas of organizing opera houses as not-for-profit cultural companies situated an ancient art form decidedly in the modern world.

Giulio Gatti-Casazza

“Even the greatest genius,” he writes, “would not be able to change the nature of things and prevent the theater from being a great public service; its two faces, artistic and economic, must be wisely harmonized, to ensure the survival of an organism that is so schematic, but not less alive.” Gatti-Casazza was born in Udine but spent his formative years in Ferrara. He studied naval engineering, but his love of opera compelled him to take on the role of general manager at the Teatro Comunale in Ferrara. His way of combining knowledge of opera, his love for music and his gift for management soon attracted attention elsewhere.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Love Duet”

At the recommendation of Arrigo Boito, Gatti-Casazza became the general manager of La Scala, and he oversaw the premiere of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. And as you might know, he brought with him a 29-year old gifted conductor from Parma by the name of Arturo Toscanini!

Arturo Toscanini

He approached his appointment with an almost maniacal passion for organization. Guided by instinct, curiosity and a clear project vision, he made radical changes in Milan. He turned the opera house into a not-for-profit institution dedicated entirely to lyric art. In addition, his vision and unshakable faith in the power of Art meant that the repertoire at La Scala was no longer confined to native composers but reflected wider European operatic expressions. His approach quickly raised eyebrows in Paris and Vienna, and came to the attention of Otto Kahn, chairman of the Met board. He strongly believed that the company needed a robust and creative leader for the future.

Giacomo Puccini: Il Trittico, “Gianni Schicci-O mio babino caro”

Gatti-Casazza arrived in New York in 1908 and brought Toscanini with him. Toscanini became the guiding artistic presence—at least until 1915—and Gatti-Casazza engaged the most important singers of the day, starting with the young Enrico Caruso and Geraldine Farrar. He brought Puccini to New York to oversee a production of Madama Butterfly as well as commissioning La Fanciulla del West and Il Trittico. Listening to Verdi’s advice, Gatti-Casazza made it his vision to have a full house every night, and Toscanini made it a priority to elevate the Met orchestra and chorus into great virtuoso artists. But what is more, Gatti-Casazza was eager to adopt new technologies and made audio recordings of the Met’s leading singers. He also initiated live radio broadcasts of opera from the Met stage, creating the template that still informs the Met transmissions on satellite radio and HD broadcasts in cinemas worldwide.

Engelbert Humperdinck: Hansel and Gretel, “The Witch’s Ride”

In a number of short years, Gatti-Casazza had turned opera into a cultural product in the corporate sense. High-quality productions combined with a self-sufficient business model raise funds without a single dollar of public subsidy. His brilliant insights into the needs of the business helped him to overcome a number of severe predicaments. Toscanini resigned and returned to Italy in 1915, and WWI prevented many European singers from coming to New York.

Giacomo Puccini with Giulio Gatti-Casazza, David Belasco

and Arturo Toscanini in New York

Responding to that need, Gatti-Casazza spearheaded the development of American talent. Under Gatti-Casazza’s leadership, the Met even survived the stock market crash of 1929 and the prolonged depression. He looked at every crisis not as a danger but as an opportunity. Although he never fully mastered the English language, he insisted that operas be done in their original languages if possible. Gatti-Casazza left New York in 1935, but only after having introduced his last great discovery, the soprano Kirsten Flagstad.

Thursday, July 4, 2024

Wednesday, July 3, 2024

Puccini: Madama Butterfly, "Un bel di vedremo" - Asmik Grigorian - 2023

Sunday, March 24, 2024

Bravo! Italian Embassy brings a night of opera to Tondo’s youth

CULTURAL EXPOSURE More than 600 students and residents of Tondo district in Manila gather at the covered court of SanPablo Apostol Parish Church on Saturday night to experience Italian culture through the staging of Giacomo Puccini’s one-act opera “Gianni Schicchi,” performed by members of the Manila Symphony Orchestra. —PHOTOS BY RICHARD A. REYES

By: Jane Bautista - Reporter / @janebautistaINQ

Philippine Daily Inquirer / 05:40 AM March 25, 2024

The Italian Embassy’s “social experiment” of introducing Italian opera to children and adolescents in Tondo, Manila, had turned out to be not just a learning experience for the young audience but also a night of entertainment last Saturday night.

“My favorite part was when [the characters] were scrambling to find their names in the will for their inheritance,” said 9-year-old Dhenvey, who was among the audience regaled by Giacomo Puccini’s one-act opera “Gianni Schicchi,” as performed by members of the Manila Symphony Orchestra (MSO) at San Pablo Apostol Parish Church on Velasquez Street.

“Gianni Schicchi” revolves around the story of the Donati family which seeks to change the will of their deceased aristocrat relative Buoso Donati to inherit his fortune. They enlist a peasant, Gianni Schicchi, to impersonate Buoso so they can dictate a new will.

Opera, the genre of musical theater that began in Italy in the late 16th century, had its audience in the country during the colonial era until the American rule, and continued to thrive past the postwar era with various efforts to promote the genre to a wider audience.

In a roundtable meeting with Inquirer editors and reporters earlier this month, Italian Ambassador Marco Clemente cited the embassy’s support behind a double-bill Puccini performance at Hyundai Hall at Areté in Ateneo de Manila University on March 16 and March 17.

The event served as a fundraising drive for the foundation bearing the name of the MSO, a pioneering orchestra in the country founded in 1926 by Austrian-Filipino conductor and pianist Alexander Lippay.

‘Bring music to everyone’

Clemente said the embassy opted to bring opera to Tondo’s youth because they didn’t want the young audience to feel intimidated in a setting outside their community.

“Gianni Schicchi” was performed before an audience of 620 students between Grade 5 and college, all scholars of the Canossa-Tondo Children’s Foundation Inc. (CTCFI).

MSO conductor Marlon Chen said that as performers, “we want to bring music to everyone.”

“That’s why the orchestra is called the symphony for the people, so we’re always up to the task no matter where we are … It was challenging but we adjust, that’s what we do,” Chen said in a brief interview after the one-hour show.

Throughout the performance, there were short pauses to explain to the audience what would happen in an upcoming scene in the opera.

Since the songs were in Italian, the scenes were broken up, so to speak, to keep the audience “up to date,” Chen said.

Before the first scene, for example, two of the performers first explained to the young audience the simple meaning of opera, being essentially a drama set to music—“musika at istorya.”

The children, as if taking part in a classroom exercise, were instructed to repeat the two words, when asked: “Could you remind us once more of the definition of an opera?”

During the scene where members of the Donati family were searching for Buoso’s last will, the actors went down the stage to mingle with the audience, asking the kids if they saw the document.

Dhenvey, along with his friends Dylan, 11, and Janno, 8, who were seated behind this reporter, appeared to be deeply engaged in the story, with one of them even explaining what was happening to his seatmates as the scenes unfolded.

After the show, Dhenvey said in an interview that he actually knew the plot because he was one of the few kids selected to watch the Ateneo performance.

“We were amazed by [the actors’] voices,” the boy said, adding that unlike in the Tondo performance where the scenes were briefly explained by the actors, the Ateneo show had subtitles instead.

‘Very enthusiastic’

In his keynote speech during the event, Clemente described the Tondo performance—one of nine events organized by the embassy as part of a cultural festival—as “historical [since this was] the first time that we bring Italian classical music, [a] fully staged opera, on this stage.”

“Tondo is very close to the Italian Embassy,” Clemente told the audience. “There’s this special bond that unites you and the Italian Embassy.”

Sought for comment about this endeavor to bring opera in Tondo, poet and journalist Pablo Tariman said, “Thus far, [there is] no history of opera being staged in Tondo. But it is possible that opera thrived in Teatro de Tondo in 1841. But not documented.”

Tariman said further research was needed, but he cited early theaters in Manila during the Spanish to American periods such as the Teatro Lírico, Teatro Español and Teatro del Principe Alfonso.

Marco Clemente

He said opera these days could be staged anywhere and not necessarily in a regular opera house, as he noted, for example, initiatives of the opera group of Viva Voce under soprano Camille Lopez Molina, who staged operas in a Baguio restaurant in 2015.

He recalled that before the Cultural Center of the Philippines was closed for renovation, the Italian Embassy, in partnership with the Department of Education, invited students to watch a performance of Puccini’s “Turandot.”

“They were very enthusiastic. Exposure of students to opera will bring about a new generation of audiences for the art form,” said Tariman, a veteran of media reporting on the arts, who is coming out with his second book, “Encounters in the Arts,” in May.

“As of now, the opera is identified with senior citizens and that is because the young people think opera is not enjoyable compared to what they get from pop music. But once given the opportunity to watch it, opera is [a] big deal among young people,” he added.

‘Dignity and honor’

Italian priest Giovanni Gentilin, vice president of CTCFI, said that in his more than three decades of service to the community in Tondo, it was his first time to see people in the music field of orchestras reach out to young people, “especially those in difficult situations,” and share a part of Italian culture with them.

According to him, the event offered “more dignity and honor to the community where the Canossian fathers are serving.”

CTCFI managing director Teresita Carmelo said she hoped the opera would serve as an “inspiration” for the children in their community.