by Georg Predota, Interlude

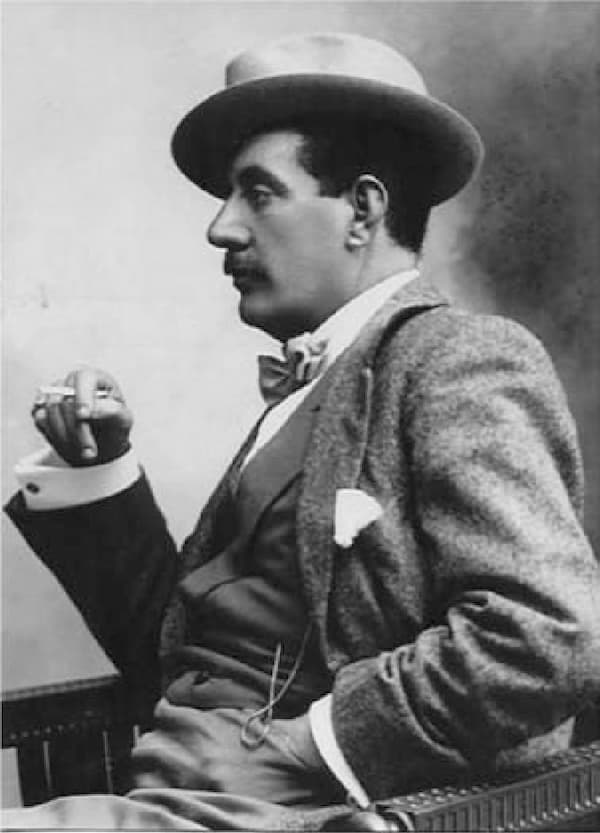

Giacomo Puccini

One of the most important and influential composers in the history of opera, Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) produced works of emotional depth, melodic beauty, and rich orchestration. Bringing a new level of realism and expressiveness to the genre, Puccini’s masterworks are famous for their vivid characterisations and the ability to convey complex human emotions.

As Michele Girardi writes, “Puccini revolutionised Italian opera by mastering the orchestra and introducing bold harmonic progressions, aligning with European trends rather than traditional Italian styles. His innovative blending of lyrical vocal lines with intricate orchestral textures produced tender moments of sublime vocalism nestled within the passionate “verismo” style.” On the occasion of Puccini’s birthday on 22 December, let us explore this revolutionary composer through his music.

Giacomo Puccini: Turandot, “Nessun Dorma”

Early Days

Giacomo Puccini

Giacomo Puccini, born on December 22, 1858, in Lucca, Italy, was part of a prominent musical family that had held the position of maestro di cappella for over a century. His father, Michele, was a church organist and choirmaster who died when Puccini was only six, marking a significant turning point in his life. Despite early academic struggles, including a reputation for being a bit of a troublemaker, Puccini pursued music under his uncle and later at the Pacini School of Music, eventually earning a diploma in 1880.

Giacomo Puccini continued his studies at the Milan Conservatory, composing his first Mass and submitting the Capriccio Sinfonico, a work that earned him recognition, as his graduation project. His first opera, Le Villi, dates from 1884 and was the result of a collaboration with poet Ferdinando Fontana. Puccini continued to revise and expand the opera, and the final version was issued in 1889. In terms of harmonic delicacy and dramatic orchestration, it laid the foundation for his future opera career.

Giacomo Puccini: Le Villi, “Torna ai felici di”

Edgar and Beyond

Giacomo Puccini’s Edgar

Based on a poem by Alfred de Musset, Puccini’s next opera Edgar premiered at La Scala in 1889. Lacking dramatic cohesion and despite a number of revisions, the work was poorly received and ultimately was Puccini’s only true failure. However, Puccini clearly learned his lesson and Manon Lescaut of 1893 became a great success. The libretto underwent a rather complicated development until librettist Luigi Illica strengthened the score and improved the drama.

A scholar writes, “drawing from Wagner’s idea of the leitmotif and combining it with the Italian dramma in musica, Puccini advanced the integration of music and drama.” In other words, Puccini uses recurring themes to represent the emotions and destinies of his characters, as Manon’s theme is repeated throughout the opera, symbolising the heroin’s fate and relationship with her lover. According to scholars, “Puccini’s skilful use of symphonic structures and thematic relationships in Manon Lescaut pushed the boundaries of the operatic genre.”

Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut, “Sola perduta abbandonata”

Realism and La Bohème

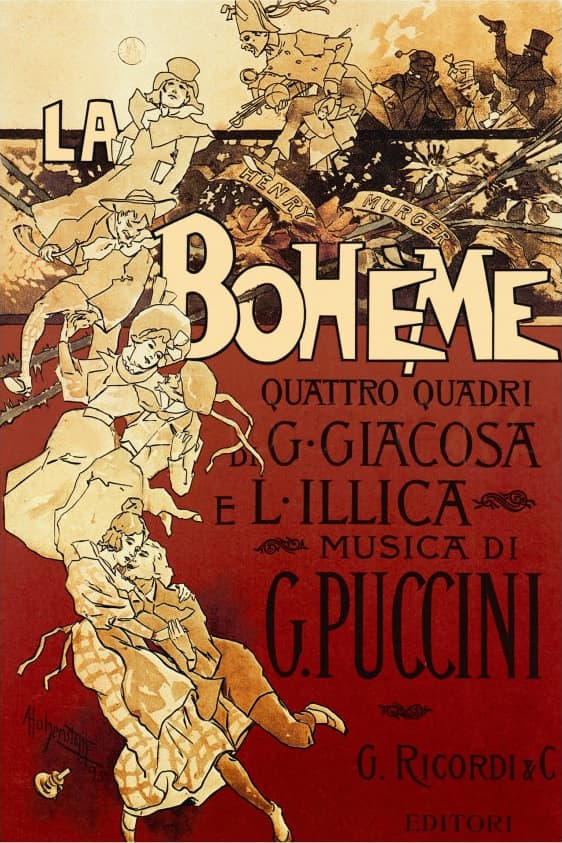

Giacomo Puccini’s La Bohème

La Bohème is based on Henri Murger’s Scènes de la vie de Bohème, a collection of loosely related stories all set in the Latin Quarters of Paris. Puccini collaborated with librettists Illica and Giacosa to create a seamless integration of text and music. In fact, a good many people consider it Puccini’s finest libretto. La Bohème, premiered in 1896, stands out for its blend of realism and poetry. Puccini moved beyond traditional operatic forms by using continuous music to reflect everyday life.

Puccini uses lyrical melodies, varied orchestration, and recurring motifs to deepen emotional and narrative impact. The opera’s realism is highlighted in the second scene with dynamic and fast-paced action as cinematic events bring the environment to life. A scholar writes, “a cyclical structure elevates the personal tragedy to a universal level, leaving the sorrow fixed in the timeless realm of art.” In Bohème, Puccini was able to achieve that perfect balance of realism and romanticism, of comedy and pathos, which makes it one of the most satisfying works in the operatic repertory.

Giacomo Puccini: La Bohème, “Quando m’en vo”

Realism and Tosca

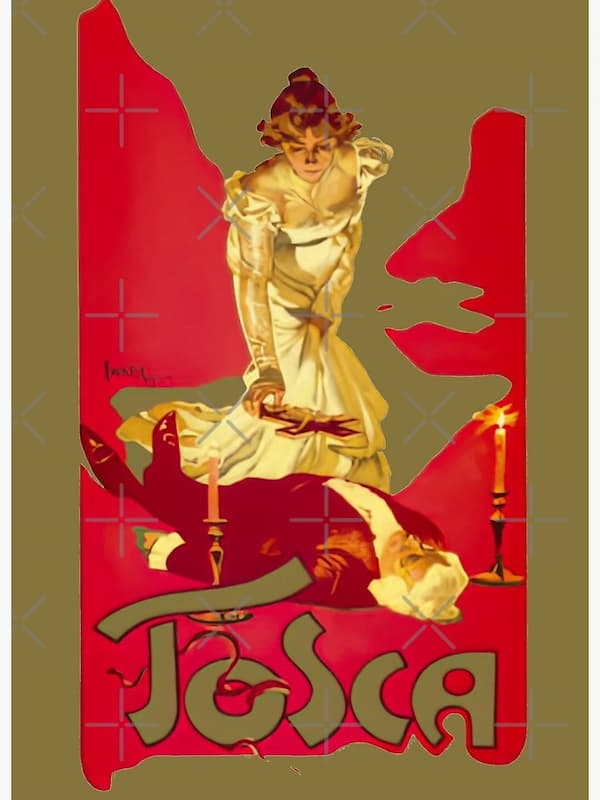

Giacomo Puccini’s Tosca poster

In Tosca, Puccini focused on personal conflicts rather than social status. The story pits the passionate opera singer Floria Tosca and the painter Mario Cavaradossi against the heinous chief of police, Baron Scarpia. The opera explores the fleeting nature of Tosca and Cavaradossi’s love against a backdrop of political and religious conflict. The operatic realism is grounded in historical details and in the choice of three famous Roman locations.

Tosca is the most Wagnerian of Puccini’s operas. It musically relies on a web of musical leitmotivs, providing glimpses of a character’s thoughts and emotional state. Puccini’s musical language, featuring diatonic melodies and successions of unrelated chords, perfectly complements the theatrical and dramatic aspects of the work, and his blending of dramatic realism with modern operatic technique “marked his entry into the 20th century.”

Giacomo Puccini: Tosca, “Vissi d’arte”

The Exotic

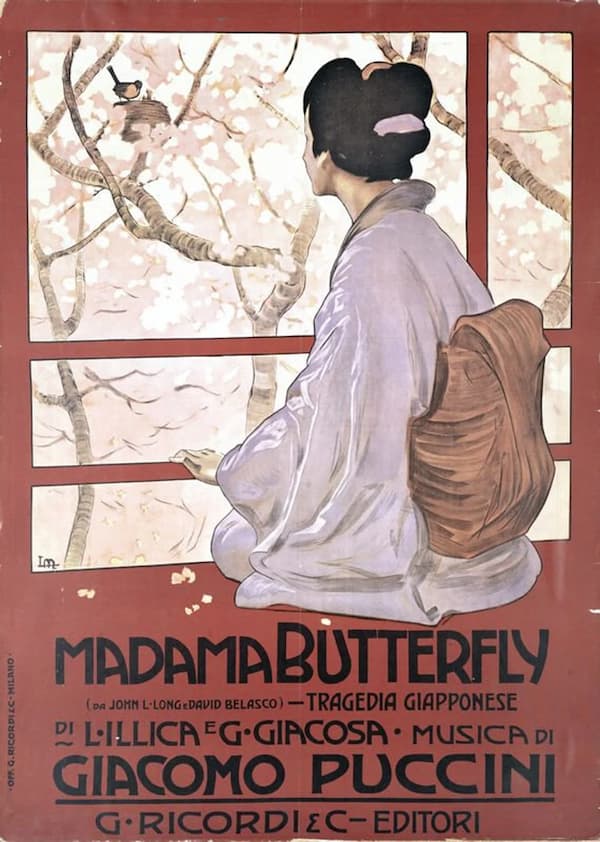

Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly

Puccini saw the one-act play Madame Butterfly, written and produced by the American playwright David Belasco in London in 1900. Drawn to the emotional depth of the story, Puccini crafted a powerful exploration of love, delusion, and tragedy. In terms of music, Puccini was striving for a sense of Japanese authenticity, engaging in exhaustive research to find, or at least approximate that sense of musical identity.

In all, Puccini revised his Butterfly for a grand total of five times, with the 1907 version considered to be his final say. In Butterfly, Puccini found a wonderful balance between the sentimental and the overwhelming, as moments of great delicacy alternate with emotional outbursts. The conflict is both personal and cultural, and through his unforgettable melodies, not to mention his sophisticated style of orchestration that cleverly aligns specific instrumental groups and orchestral timbres to match distinct dramatic moments, Puccini’s timeless creation will continue to resonate on a variety of psychological and cognitive levels.

Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly, “Vogliatemi bene”

Evolution

Giacomo Puccini’s La fanciulla del West poster

Puccini called his opera La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the West) his “greatest work.” The work had been seven years in the making and originated during a period of severe family strife. As his long-time collaborator Luigi Illica had died in 1906, Puccini struggled to find a replacement. Puccini was also looking for new directions as he had grown disillusioned with conventional opera genres. A scholar writes, “La fanciulla departs from his earlier operas’ reliance on strict realism and instead delves into more symbolic, emotional expression.”

The opera’s dramatic complexity, innovative use of orchestration, and its departure from rigid realism show a composer at the height of his powers, experimenting with new ways to connect with modern audiences. Clearly, he was not able to please everyone as a good many commentators suggested that Puccini’s music represented a debasement and cheapening of pure Italian values. And his considerable fame abroad was seen as proof that the composer had “wilfully sacrificed national character for cheap commercial exploitation.”

Giacomo Puccini: La fanciulla del West, “Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano”

Unity

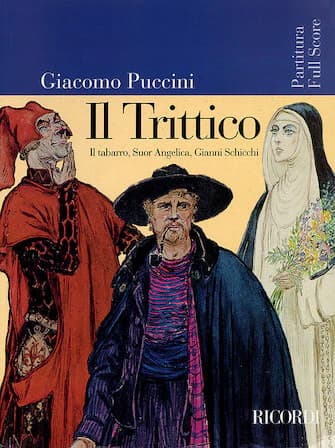

Giacomo Puccini’s Il Trittico recording cover

After the success of La fanciulla and La Rondine, Puccini eagerly explored this convergence of theatre and music. He began work on a one-act opera in 1913, however, he ended up with a collection of three one-act operas entitled Il Trittico. Comprising Il Tabarro (The Cloak), Suor Angelica (Sister Angelica), and Gianni Schicchi, Puccini attempted to draw together three different operatic genres, the dramatic, sentimental and comic, respectively, in a single project.

In Il trittico, Puccini shows himself to be the undisputed master of musical-dramatic continuity. This continuity becomes apparent within both the constraints of each singular one-act opera, as well as spanning a whole evening of operatic entertainment. This fascinating exploration of contrasting genres continues to be “one of the most innovative and complex works in the operatic canon.”

Giacomo Puccini: Gianni Schicchi, “O mio babbino caro”

Final Effort

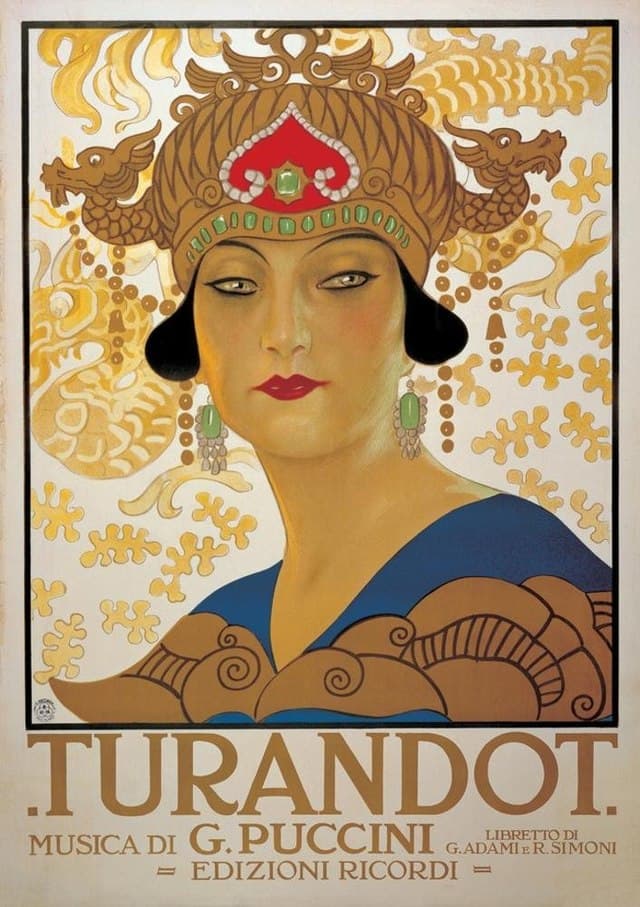

Poster of Turandot‘s performance

Puccini began working on his opera Turandot in the winter of 1919/20, urging his librettists Adami and Simoni to supply him with an Italian translation of Schiller’s adaptation of Carlo Gozzi’s play. Depicting distant lands and customs was a centuries-old musical tradition and Puccini demanded to “find a Chinese element to enrich the drama and relieve the artificiality of it, and to make use of Chinese syllables to give it a Chinese flavour.”

Puccini, once again, looked for a sense of authenticity in this musical characterisation. He visited a former diplomat in China, who owned a music box of genuine Chinese tunes. Three melodies from this music box ultimately found their way into the operatic score. Puccini left his last and most ambitious project unfinished, and Turandot has been described as “the last great Italian opera.”

However, much of the work is not Italian, as it draws on other cultures. Yet, it is in no way authentically Chinese either. A scholar writes, “it is a Western projection of the East, rife with contradictions, distortions, and racial stereotypes, and yet is also one of the most exhilarating and impressive works ever to take the operatic stage.”

No comments:

Post a Comment