by

But do you know about Rosalyn Tureck, the incredible keyboard player who inspired him?

Over the course of her very long career, Rosalyn Tureck wore countless hats as a pianist, theremin player, harpsichordist, keyboard player, composer, conductor, teacher, and all-around great musical thinker.

Rosalyn Tureck

Today, we’re looking at her life, including the mystical experience in a Juilliard practice room that changed the course of her career, her fascinating experiments with very new (and very old) instruments, and how her playing inspired a young Glenn Gould.

Rosalyn Tureck’s Early Education

Rosalyn Tureck was born on 14 December 1913 in Chicago to two Russian-Jewish immigrants.

Her whole family was musical. Her grandfather worked as a cantor in Kiev, and her mother taught her three daughters to play piano.

When Rosalyn was nine, she began taking lessons from Sophia Brilliant-Liven. Brilliant-Liven had an impressive resume: she’d studied under Anton Rubinstein, the pianist who had founded the St. Petersburg Conservatory.

She was also a strict teacher. Tureck later remembered that for an entire four years, she never received a single compliment.

The first compliment came after Rosalyn won a major competition at thirteen. Brilliant-Liven heard her performance and told her, “If I had been listening from outside the auditorium, I would have sworn it was Anton Rubinstein himself playing.”

A Fascination With New (and Old) Technology

Rosalyn Tureck

From an early age, Tureck demonstrated what would become a lifelong interest in new musical technology.

She was especially taken by an electronic instrument called the theremin, which was patented in 1928. When she was ten years old, she had the opportunity to meet the instrument’s inventor, Leon Theremin. It wasn’t long before she was playing Bach on it.

At sixteen, she realised she could use her theremin expertise to secure a scholarship. She went on to make her Carnegie Hall debut on the theremin – not piano – in 1932.

Around the same time, Tureck also began studying with pianist and harpsichordist Gavin Williamson in Chicago. In the 1920s, when there were only a couple of dozen harpsichords in the country, Williamson and his partner Philip Manuel went to Paris to commission a reproduction. They played a major role in resurrecting the instrument in America.

Williamson passed along his love of the harpsichord – and especially Bach as played on the harpsichord – to Tureck.

Revelations at Juilliard

Rosalyn Tureck

When Tureck auditioned for Juilliard in 1931, the audition committee asked her to play a Bach Prelude and Fugue. She asked, “Which one?” Turns out she had all of them memorised and was prepared to play any.

Needless to say, she was accepted into Juilliard. She began studying with Olga Samaroff, a teacher well-known for encouraging the unique creative voices of her students.

One day, while at Juilliard, she had an epiphany about the works.

One Wednesday, I started studying the Fugue in A minor from the WTC First Book.

At a certain point, I lost consciousness, and when I regained it, I had a sort of revelation. All of a sudden, I had within my reach a penetration of Bach’s structure, of his entire sense of form…

A door had opened for me on an entirely different world.

This epiphany at college would form the basis of her professional specialty.

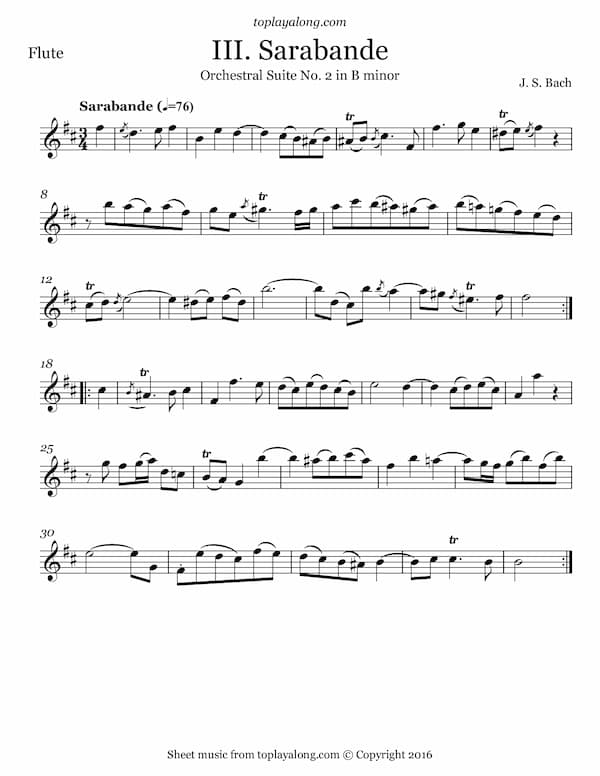

Rosalyn Tureck playing Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in A Minor

Promoting Bach

In 1937, Tureck played six all-Bach concerts in New York City. Such a specialty was unusual at the time. She began presenting these performances annually.

It took time to win over the critics, but she eventually did. In 1944, the New York Times wrote about her performance of the Goldberg Variations that she “gave each variation with so distinctive a character and with such verve and vitality that the listener had the illusion of hearing Bach himself playing them on the harpsichord.”

Other musicians were also engaging with Bach’s keyboard works around this time. In 1946, harpsichordist Wanda Landowska made a recording of the Goldberg Variations, and it sold unexpectedly well.

Tureck went into the studio herself in 1947, creating her own recording of the Goldberg Variations.

In 1949, a sixteen-year-old Glenn Gould came to one of her New York Bach concerts. He was absolutely dazzled by her and her recordings.

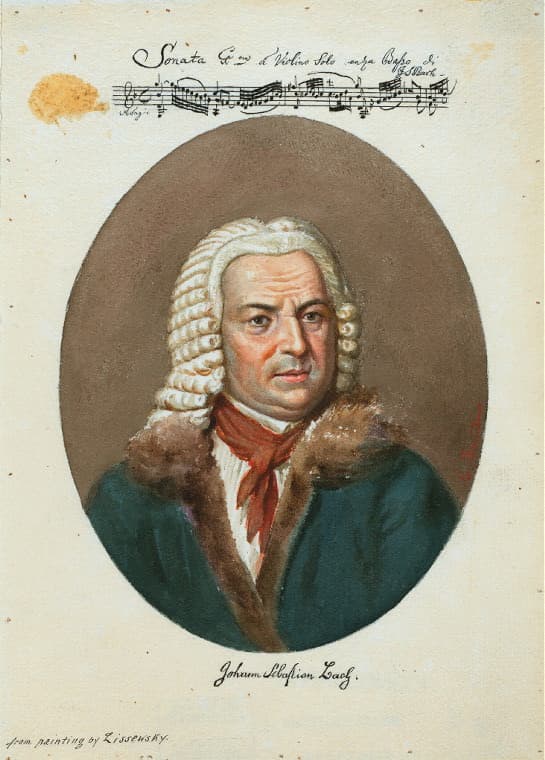

Glenn Gould at the piano

He later remembered Tureck:

She was the first person who played Bach in what seemed to me a sensible way. It was playing of such uprightness, to put it into the moral sphere. There was such a sense of repose that had nothing to do with languor, but rather with moral rectitude in the liturgical sense.

He also said:

I was fighting a battle in which I was never going to get a surrender flag from my teacher on the way Bach should go, but her records were the first evidence that one did not fight alone.

Gould himself went on to make his own legendary, hugely influential recording of the Goldberg Variations in 1955.

Embracing New Technology

Leon Theremin © thereminworld.com

Tureck’s expertise didn’t stop at Bach. Even during her time at Juilliard, she began exploring her interest in electronic instruments. She actually began studying the theremin with Theremin himself.

Later, she’d become fascinated with the artistic possibilities inherent in electronic keyboards.

For twenty years, she worked with researcher Dr. Hugo Beniof, a seismologist who worked at CalTech and was developing electronic keyboards. The two wanted to create an instrument that played like a piano and had a wide dynamic range.

After Beniof’s death, despite the fact that the instrument had never been truly perfected, a performance featuring it was organised at the Hollywood Bowl. Marketing materials heralded that the electronic piano would be louder than an entire orchestra.

The invention was conceptually interesting and pushed the bounds of technology at the time. Unfortunately, in the end, it turned out that a loud piano had limited commercial appeal, but it was still a testament to Tureck’s fascination with pushing boundaries.

Contemporary Music

Rosalyn Tureck

Tureck also loved contemporary music, championing many new works over the course of her career.

She premiered Copland’s challenging piano sonata in Britain; Diamond wrote his first piano sonata in 1947 for her; and she premiered William Schuman’s 1942 piano concerto.

In 1949, she founded the Contemporary Music Society, and she ran the organisation until 1953.

She even composed herself, even studying for a time with Schoenberg. In 1952, in the words of her obituary, “she presented the first programme in the United States of tape and electronic music.”

Travels and Teaching

For decades, Rosalyn Tureck traveled across America and the world giving performances.

She founded her own orchestra – the Tureck Bach Orchestra – which performed between 1960 and 1972.

She also became the first woman to conduct at a New York Philharmonic subscription concert in 1958. Leonard Bernstein conducted the program, but he stepped aside during the Bach concerto so that she could conduct from the piano.

Teaching was a major part of her life. Over the course of her career, she taught at a number of institutions, including the Philadelphia Conservatory, the Mannes School of Music, Juilliard, Columbia University, and Oxford.

She was also the author of a number of books, including the three-volume Introduction To The Performance Of Bach, and also edited editions of various Bach works.

The list of musical organisations she founded is staggering. Here’s the list in her obituary:

“Composers of Today, New York City, 1949-53; the International Bach Society in 1966, and the Institute for Bach Studies, New York, two years later; the Tureck Bach Institute, New York, 1966-90; and last but not least, the Tureck Bach Research Foundation (TBRF) of Oxford in 1993.”

Final Years and Legacy

Rosalyn Tureck

In the 1990s, Tureck moved to Oxford to oversee the TBRF. Her wide-ranging interests and huge personality proved to be irresistible.

In the words of her obituary:

The TBRF held an annual symposium at which distinguished speakers from different disciplines – ranging from music to astrophysics and Egyptology – addressed the same topic, such as structure or embellishment.

At those meetings, Tureck played Bach on everything from the harpsichord to the Steinway and the synthesiser – often on several instruments during one concert – and she had little patience for the restrictive attitudes that declared Bach should only be played on historical instruments.

Rosalyn Tureck died in July 2003. She left behind a reputation for being one of the most imaginative keyboard artists of the twentieth century.