by

Music is always an important part of any funeral service or memorial service.

The right choice of music can pay tribute to the deceased’s tastes and provide comfort to the mourners left behind.

Have you ever wondered what music the great composers had performed at their funerals? Today, we’re looking at four fascinating composer funerals – and the music that was played at each of them.

George Frederic Handel (1759)

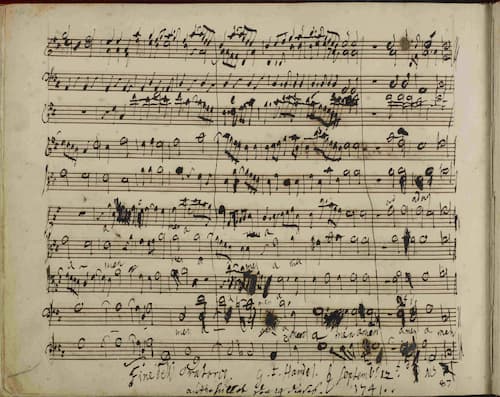

Marble statue of Handel, 1738

In August 1751, sixty-six-year-old composer George Frederic Handel developed a cataract in one eye. His vision began deteriorating, especially after a procedure conducted by a quack surgeon.

By the following year, he was totally blind and no longer able to compose.

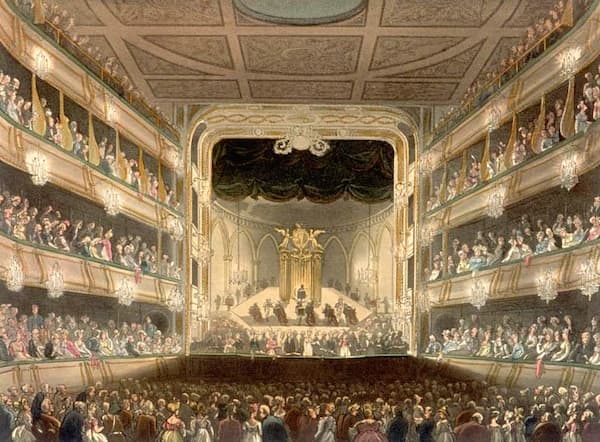

He died in 1759. Although he had been born in present-day Germany, he had become a celebrity during his time in England. Accordingly, he was granted the privilege of a state funeral at Westminster Abbey.

He died on 14 April, and his funeral was held on 20 April. The Bishop of Rochester officiated, and over three thousand mourners attended.

Three choirs collaborated on a performance of Funeral Sentences by composer and organist William Croft.

These works have been performed at many famous British funerals since, including Winston Churchhill’s, Princess Diana’s, and Queen Elizabeth II’s.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1791)

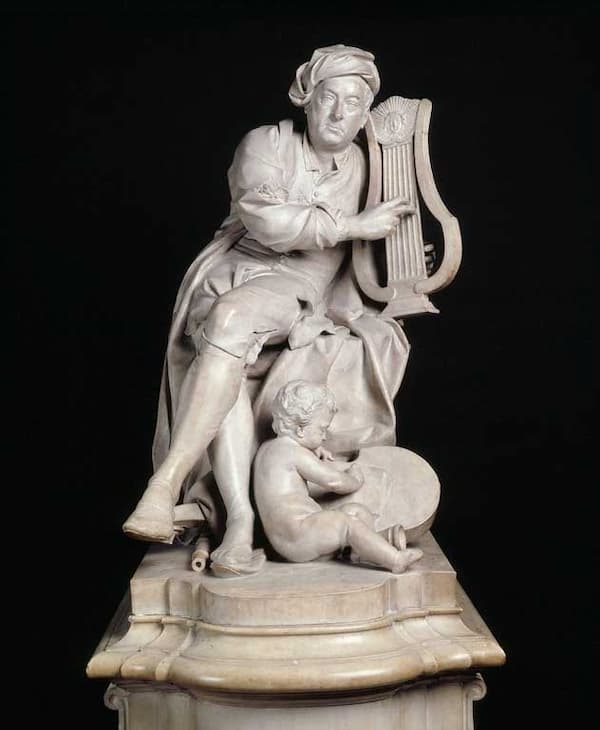

Engraving (1860) representing Mozart’s burial © wordsmusicandstories.wordpress.com

Historians disagree about the cause of Mozart’s death and the length of his health decline during the autumn of 1791.

However, it is known that by 20 November, he was bedridden, in pain, and vomiting.

He died on 5 December at his home, a little after midnight. The Requiem he was working on was left unfinished.

Mozart’s funeral was planned by his friend and patron Baron Gottfried van Swieten. It took place on 10 December at the parish of St. Michael in Vienna.

A portion of his unfinished Requiem was played at the service. The only movement that Mozart had completed and that was ready for performance was the opening “Requiem aeternam” from the Introitus section.

Scores for a few more movements based on sketches were quickly rounded out by Mozart’s student Franz Jacob Freystädtler, who completed the unfinished portions of the remaining movements, such as the Lacrymosa, Sanctus, and Benedictus.

Completion of the other movements was later tackled by another Mozart student named Franz Xaver Süßmayr.

The musicians who performed at Mozart’s funeral volunteered their services to pay tribute to their dead colleague.

Learn more about Mozart’s funeral.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1827)

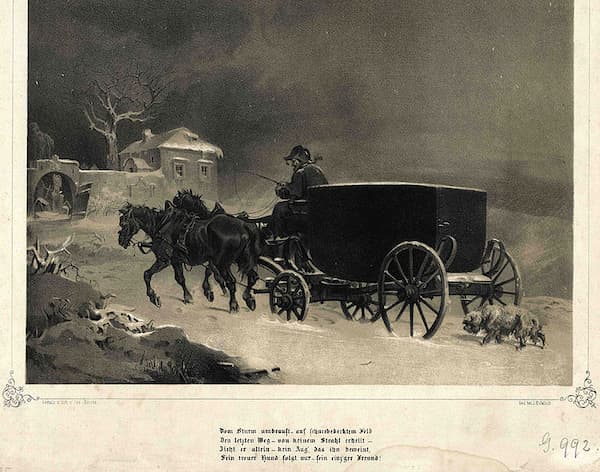

Beethoven’s funeral as depicted by Franz Xaver Stöber © Wikipedia

By the time of his death in 1827, Beethoven’s health had been deteriorating for years.

Of course, his deafness was his most famous health complaint, but he also struggled with liver failure, pneumonia, and alcohol addiction.

He died in the early evening of March 26.

The funeral was a massive event. It is estimated that between 10,000 and 30,000 mourners lined up on the surrounding streets to pay tribute, or at least catch a glimpse of him.

His pallbearers included composer Johann Nepomuk Hummel, piano pedagogue Carl Czerny, and composer Franz Schubert.

Beethoven had not left specific instructions about what music he wanted to have performed at his funeral. Conductor and composer Ignaz von Seyfried took on the responsibility of providing music for the event.

Seyfried picked out two of Beethoven’s Three Equals, works for trombone ensemble that had been commissioned for All Souls’ Day in 1812. Seyfried rearranged them to include a men’s chorus.

Next he arranged the third movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 12, a funeral march, again for trombone and men’s chorus.

He also conducted a “Chorale of the Brethren of Charity” from incidental music for Wilhelm Tell by now-forgotten composer Bernhard Anselm Weber.

To wrap it up, Seyfried offered his own “Libera me”, which quoted Mozart’s Requiem.

The bigger musical tribute came a few days later after the funeral proper at a commemorative performance. There the entire Mozart Requiem was performed in full.

Learn more about Beethoven’s funeral.

Frédéric Chopin (1849)

Pianist and composer Frédéric Chopin had endured severe chronic illness throughout his adult life.

However, during the 1840s, it became clear that his tuberculosis infection was likely going to kill him.

In 1842, he wrote to a friend that he was so sore and fatigued that he was lying in bed for the day.

On 15 October 1849, it became clear that the end was finally near. Musical visitors came and performed for him to provide comfort. He finally died on 17 October.

The funeral took place on 30 October. Chopin’s fame was such that tickets had to be printed for the event. Thousands of people came from around Europe to pay tribute, but only four thousand ticketed mourners were allowed into the Church of the Madeleine.

The music had been carefully chosen by Chopin himself and included Mozart’s Requiem. The archbishop himself had to issue special dispensation to allow women singers to sing in church, as long as they performed behind a black curtain.

Other musical offerings included organ arrangements of his fourth and sixth piano preludes, as well as the funeral march from his Piano Sonata No. 2.

For more of the best in classical music, sign up for our E-Newsletter