by Georg Predota, Interlude

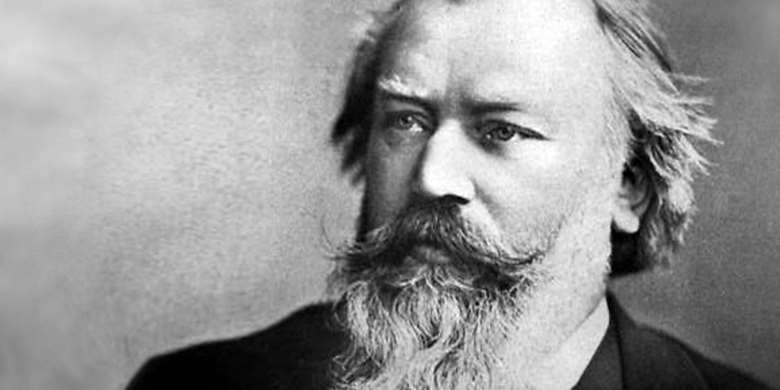

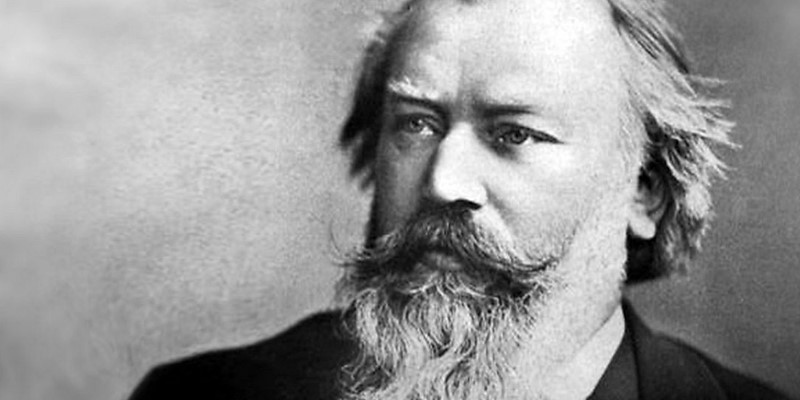

Anton Bruckner © Ludwig Grillich

His compositions, relying on a highly idiosyncratic and expansive musical style, helped to define contemporary musical radicalism. A solitary man, preferring the rural surroundings of Upper Austria to the urban environments of Linz and Vienna, Anton Bruckner remains an enigma, even as we celebrate the 200th anniversary of his birthday.

Ancestry and Study

The Bruckner family lived in a small, isolated farming community for over four centuries. His grandfather was a broom-maker, and just like Schubert, Anton was a schoolmaster’s son. His father, also named Anton, did everything in his power to stimulate his son’s musical talents. As the composer later recalled, “my favourite place growing up was in church, next to my father on the organ bench.”

Young Bruckner showed some obvious talent for music, and at the age of 10, it was decided that he should be sent to musical studies with his godfather Johann Baptist Weiss. Bruckner received his first serious lessons in harmony, figured bass, and organ and violin playing. In addition, young Anton was introduced to a wider repertory of church music. After his father’s death in 1837, Bruckner was sent to the monastery of St. Florian as a chorister.

St Florian Monastery

St. Florian Monastery

Bruckner’s first stay at the Augustinian monastery of St. Florian lasted three years. The monastery was a center for the arts and science, and as part of the centuries-old music tradition, it housed the largest organ in the Danube Monarchy. Bruckner was in awe of the great instrument, later to be called the “Bruckner Organ,” and he greatly excelled in organ improvisation. He also received lessons in reading, writing, arithmetic, and organ and piano instruction.

As Paul Hawkshaw writes, “if his Roman Catholicism had already been firmly established during his boyhood in Ansfelden, it was certainly reinforced at St. Florian. The Baroque halls of the monastery were to be a source of spiritual strength and inspiration for the rest of his life.” Bruckner was a devoutly religious man who kept a log of his daily devotions and prayed before each performance. His faith in the spiritual journey towards the afterlife became a process that decisively shaped his compositional imagination as he channeled profound spiritual messages that elevated the music to the level of an undistracted prayer.

Teacher Training and Return to St. Florian

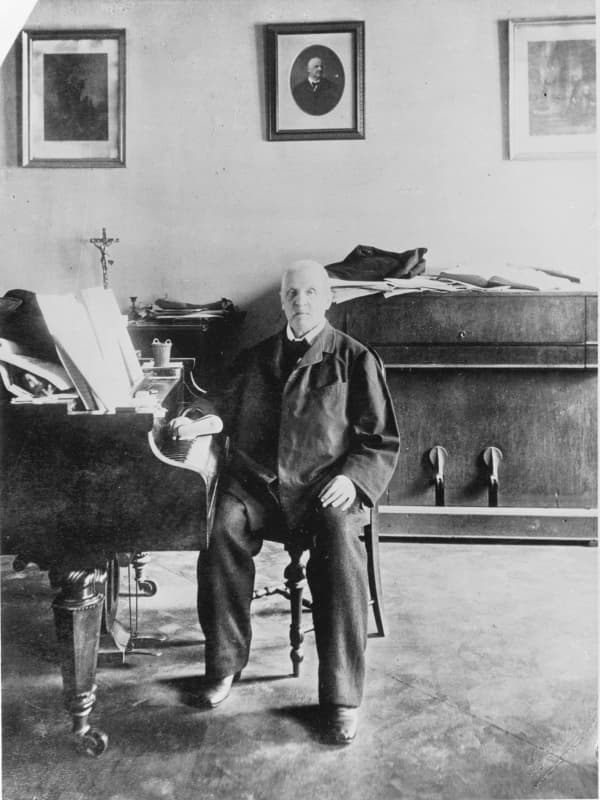

Anton Bruckner’s monument in Vienna

Despite his obvious musical abilities, Bruckner’s mother decided that he should follow in his father’s footsteps and become a schoolmaster. After taking teacher-training courses in Linz, Bruckner was sent to the remote village of Windhaag near Freistadt, where he remained as assistant schoolteacher for 16 months. A further teaching appointment saw him stationed at

Kronstorf an der Enns, but eventually, he returned to St. Florian for ten years to work as a teacher and an organist.

At the beginning of his second stay in St. Florian, Bruckner took on organ duties in the monastery church, and he dedicated himself to compositional studies aimed at improving his skills as a composer. He transcribed and analyzed works by Mozart, Michael and Joseph Haydn, and Beethoven. Bruckner remained a livelong learner, and he started to integrate these influences into his own improvisations and compositions. From about 1849 onward, almost 30 compositions were created at St. Florian.

Linz

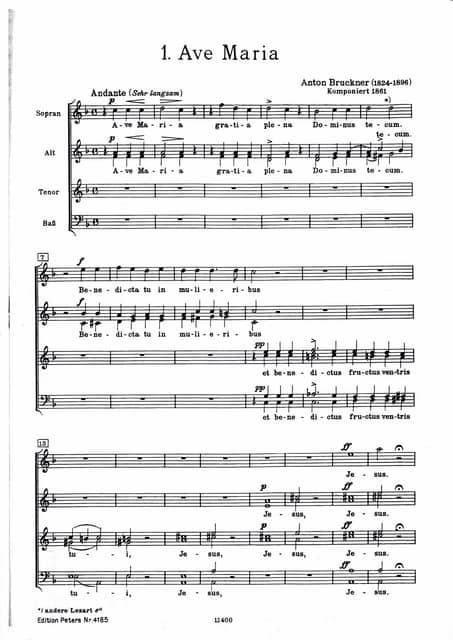

Bruckner’s Ave Maria

During the early 1850s, Bruckner became increasingly frustrated with St. Florian, and he began to set his sights beyond the monastery walls. He unsuccessfully applied for the position of cathedral organist in Olmütz, but was more successful at Linz. His provisional appointment as cathedral organist was confirmed on 13 November 1855. Bruckner greatly enjoyed his time in Linz, a period that was essentially more stable and freer from controversies.

For six years, Bruckner studied counterpoint via correspondence with the famed Viennese theorist Simon Sechter, producing thousands of pages of exercises. Sechter later confessed that he had never had such an industrious student. Bruckner even took official examinations, and in addition to his legendary reputation as an improviser at the organ, he now produced his first masterpiece, the seven-voice Ave Maria first performed at Linz cathedral on 12 May 1861.

Idol Wagner

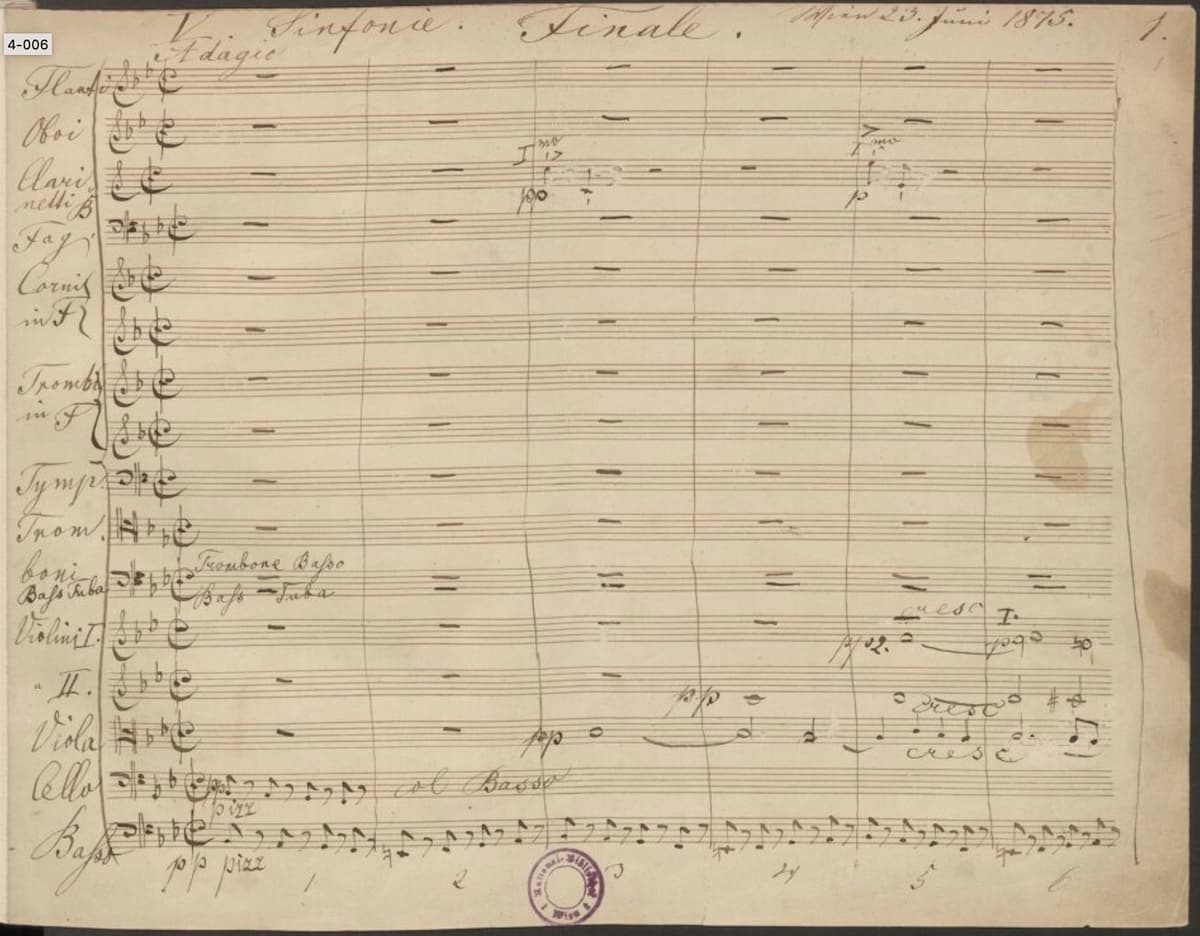

Bruckner’s autograph manuscript

In December 1861, Bruckner once again immersed himself in study, taking orchestration lessons with the German cellist and conductor Otto Kitzler. As Timothy L. Jackson writes, “Kitzler must be credited with bringing Bruckner up to date with 19th-century musical practices and introduced him to the music of Wagner.” For Kitzler, Bruckner composed a String Quartet, a “Study” Symphony in F minor, and a Psalm for double chorus and orchestra.

Bruckner first met his idol Wagner at the première of Tristan und Isolde in Munich in May 1865. Bruckner was fascinated by Wagner’s ideas about expanding the orchestra and his harmonic innovations, and he became a “fawning acolyte of Richard Wagner.” This hero worship would haunt Bruckner during his lifetime and posthumously. His total admiration is probably best demonstrated by Bruckner’s dedication of his Third Symphony. It reads, “To the eminent Excellency Richard Wagner the Unattainable, World-Famous, and Exalted Master of Poetry and Music, in Deepest Reverence Dedicated by Anton Bruckner.”

Vienna

The Bruckner Organ © stift-st-florian.at

Bruckner’s discovery of Wagner’s music at the age of 38 initiated a transition from meek church musician to bombastic symphonist. But first, Bruckner accepted Sechter’s post as a music theory teacher at the Vienna Conservatory. Bruckner was ill-prepared for the acidic and highly competitive musical environment of imperial Vienna. He presented a wide and easy target for music critics, journalists and composers alike, with most famously perhaps Johannes Brahms referring to him as a “country pumpkin.”

During his time in Vienna, which included an appointment at Vienna University in 1875, the symphony became the focus of his creative activity, starting with the so-called “Nullte,” No. 0. In a remarkable spurt of activity during 1870 and 1871, Brucker completed a series of four symphonies in little over two years. In general, the works were considered too long, and habitually plagued by debilitating periods of low self-esteem, Bruckner became preoccupied with revising earlier scores.

Symphonic Thoughts

Bruckner composed music that was simultaneously naïve and complex. Yet, once he had found his compositional path, the musical world did not know what to do with it. His “Wagner” Symphony No. 3 received a disastrous premiere in December 1877. Bruckner, never a successful orchestral conductor, was forced to take the podium. A scholar writes, “The orchestra was rebellious; the audience streamed out of the hall during the Finale and Hanslick wrote a blistering review.” As Bruckner reported to a friend, “I am once again alone in the face of adversity and misunderstanding.”

Amongst countless revisions of earlier works, the completion of the Fifth Symphony, a work he never heard performed during his lifetime, was followed by another remarkable series of works including the Sixth Symphony, the Seventh, the Eight, and the Te Deum. These works represent the summation of his symphonic journey. He was now blending Beethoven’s sense of preparation and suspense, mystery, and the ethical content of music with Schubert’s extended harmonies and Wagner’s unhurried and gradual unfolding of instrumental music.

Character and Reception

Bruckner’s tomb

Admirers describe Bruckner as an unpretentious, modest man and a “daring innovator who shied away from no enterprise.” Detractors, and he certainly had many, recognised his originality yet found nothing of value in the “work of a modest Viennese church musician who lived a solitary dreamlike existence without ambition, and who had been dragged into the limelight by an excessive Wagnerian cult.” To be sure, Bruckner was decidedly out of place in Vienna as he retained his peasant speech and social clumsiness, and he had the disastrous inclination to fall in love with teenage girls.

His distracting compulsions ranged from obsessive preoccupation with financial security to a morbid fascination with corpses. Bruckner was painfully unaware of the intellectual and political currents of his day, and he exhibited a “Neanderthal male chauvinism that even his admirers found remarkable.” He allowed outside influences to shape the content of his music, and untangling the relative merits of Bruckner’s various versions has kept performers and scholars busy until this very day. Bruckner’s symphonic works, much maligned in Vienna in his lifetime, are finally an integral part of the symphonic repertoire.

Bruckner died in Vienna on 11 October 1896 at the age of 72. He is buried in the crypt of the monastery church at Saint Florian, immediately below his favourite organ.