by

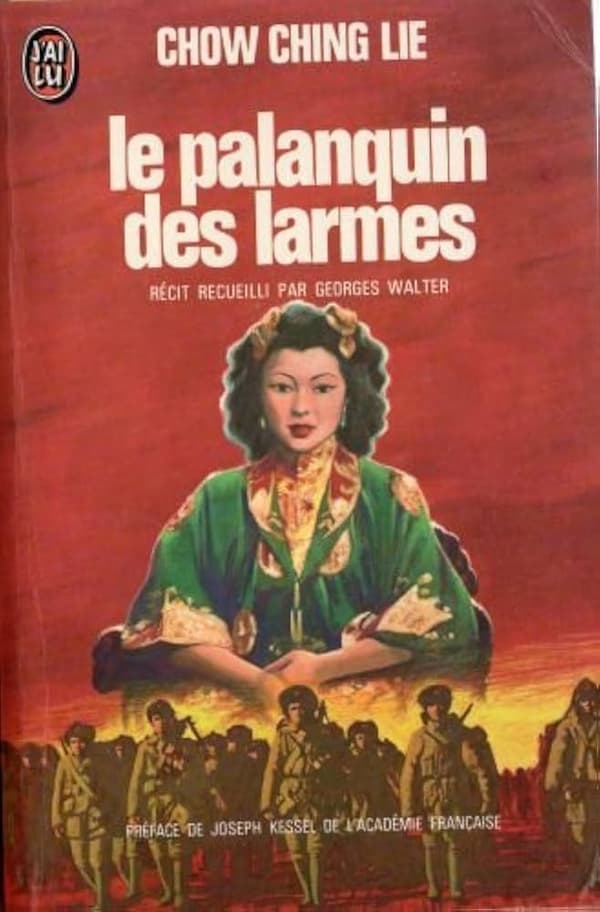

Chow Ching Lie’s personal memoir ‘Le Palanquin des Larmes’ (Journey in Tears)

Forced into an arranged marriage at the age of 13, becoming a mother by 14 and a widow at age 26, her memoirs detail her journey from a child bride to fulfilling her dream of becoming an internationally recognised pianist. It is not just a tale of personal triumph over adversity but also a critical look at gender roles, societal expectations, and a quest for personal freedom.

Chow Ching Lie Documentary Trailer

Yellow River Concerto

Her “Journey in Tears” is also a “Journey in Music,” as it becomes a source of solace in her darkest times and simultaneously a tool for empowerment. It symbolises her resilience, her fight for autonomy, and her way of reclaiming her identity. She and her two children find a new home in Paris, and by connecting with people across cultures, music becomes a profound commentary on the power of art to heal, transcend, and transform lives.

Chow Ching Lie

For Chow, who passed away on 16 February 2025, Music was always woven into the narrative of her life, highlighting significant emotional or transformative movements. It served as both a backdrop and a reflection of her personal evolution. As such, we decided to choose compositions that found thematic resonance with her life’s journey, from the melancholy of early struggles to the hopeful notes of her later achievements.

Yellow River Concerto

The Lark

Chow’s enchantment with music started at the age of six when a student at her school sat down in front of a piano to give a small recital. She writes, “this strange, shining black object stood at the centre of the stage… Suddenly, her hands flew over the keyboard like enchanted birds, and the sound that was emitted from that strange black object was more beautiful than anything I had ever heard.”

Her father rented a piano and provided first lessons to her and her sister. She managed to make considerable progress by the end of her first year. She first appeared in front of an audience at the age of 10, performing Glinka’s “Lark.” That composition would later serve as a metaphor for her newfound freedom and the sense of lightness she felt in Hong Kong. Away from the oppressive environment she had known, Chow felt that she could convey not just her technical skills but her personal joy and relief.

Glinka/Balakirev: The Lark

Moonlight Sonata

Chow Ching Lie

Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” holds a special place in Chow Ching Lie’s narrative, serving as a poignant emblem of her inner world amidst the external chaos of her life. She first played the work when she was still a young girl, trapped in the confines of her arranged marriage. For Chow, the opening movement allowed her to express the deep-seated melancholy and yearning for freedom that she was unable to voice in her real life.

The “Moonlight Sonata” reappears at various junctures, each time marking a significant milestone in her life. When she performed the work at a concert in Hong Kong, her first major performance after departing from Shanghai, it became more than just a piece of music. For Chow, it captured her journey from darkness into light, from silence to expression, embodying the essence of her transformation through music.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 14, Op. 27 No. 2 “Moonlight”

Clair de Lune

Chow Ching Lie’s performance poster in December 1973

Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” becomes a significant piece in Chow’s musical journey, particularly after her move to France. She describes her first encounter with that composition as “a revelation, as the music’s delicate and nuanced expression resonated with my soul.” Her performances of “Clair de Lune” highlight several key moments in her life, most notably at a concert in Paris.

For Chow, “Clair de Lune” became a medium through which she could share her journey of healing and self-discovery. Every note seems to echo her newfound peace and love for life, in stark contrast to the tears of her earlier years. As she called it, “this music was a way to heal from past wounds while embracing the beauty of the present.”

Claude Debussy: Clair de Lune

Alla Turca

For Chow Ching Lie, the “Alla Turca” from Mozart’s A-Major sonata represents moments of great personal joy and public acclaim. It represents music that contrasts with the much more introspective pieces she had previously associated with her life’s struggles. It came to represent the playful, confident, and exuberant parts of her personality.

The “Alla Turca” is frequently mentioned in the context of teaching music, where Chow finds delight in sharing the playful energy with her students. She vividly recalls a concert in France, where she decided to lighten the programme with a performance. Apparently, the audience, initially drawn in by her interpretations of classical works, is surprised and delighted by the sudden shift to the vibrant and spirited “Alla Turca.”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Sonata No. 11 in A Major, K. 331 “Alla Turca”

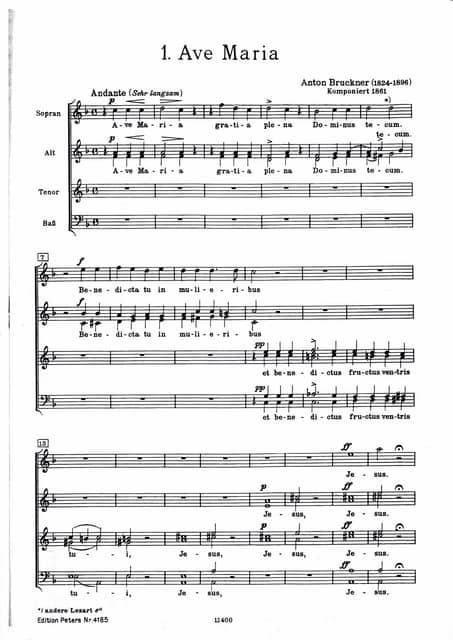

Ave Maria

Chow Ching Lie

The ideas of music and healing in Chow’s narrative are of primary importance, as music transforms her suffering into resilience and purpose. Her pursuit of music emerges as her salvation and as a means of emotional escape and eventual physical liberation. Music was not simply an art form but a powerful healing force.

The healing power of music operates on both a personal and symbolic level. Personally, it offered a way to process trauma, and symbolically, music became the conduit for transcending cultural and personal wounds. During a visit to the pilgrimage site of Lourdes, Chow was so touched by what she saw that she spontaneously started to play the “Ave Maria.” The very same piece sounded when Chow played in public for the last time; tellingly, the performance took place in a hospital under the title “Music and Healing.”

Chow Ching Lie’s Hospital Performance

Throughout Chow Ching Lie’s life, music transcended mere art and became her voice of liberation, her sanctuary amidst adversity, and ultimately the melody through which she transformed her story from one of tears into one of triumph.

Verdi described the setting of the “Ave Maria” as Scala enigmatica armonizzata a Quattro voci miste (Enigmatic scale, harmonized for four mixed voices). This enigmatic scale spans an octave and rises by a semitone and by an augmented second. It is followed by three whole tone and two semitones. It descends with two semitones followed by one whole tone and an augmented second. From there a semitone, the original augmented second, and finally a semitone concludes the descending version of Verdi’s enigmatic scale. The scale is first heard in the bass, both ascending and descending, and then in the alto, tenor and the soprano. It sounds like a harmonic and contrapuntal exercise, and originally it was not part of the Quattro pezzi sacri, but eventually the publisher Ricordi included it in the set.

Verdi described the setting of the “Ave Maria” as Scala enigmatica armonizzata a Quattro voci miste (Enigmatic scale, harmonized for four mixed voices). This enigmatic scale spans an octave and rises by a semitone and by an augmented second. It is followed by three whole tone and two semitones. It descends with two semitones followed by one whole tone and an augmented second. From there a semitone, the original augmented second, and finally a semitone concludes the descending version of Verdi’s enigmatic scale. The scale is first heard in the bass, both ascending and descending, and then in the alto, tenor and the soprano. It sounds like a harmonic and contrapuntal exercise, and originally it was not part of the Quattro pezzi sacri, but eventually the publisher Ricordi included it in the set.