The German-born English composer George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) is widely regarded as one of the greatest musical masters of his era. Indeed, his extraordinary talent and relentless dedication significantly shaped the landscape of classical music during the Baroque era.

Portrait of George Frideric Handel by Thomas Hudson, 1756

He began his musical journey in Halle, Germany, and honed his skills in Italy before settling in England. Renowned for his operas, oratorios, and instrumental works, Handel masterfully blended German, Italian, French, and English musical traditions into a distinctive and influential style.

Handel showcased his genius for dramatic storytelling and musical innovation throughout, and while his posthumous fame largely rested on a few orchestral works and the oratorio Messiah, Handel excelled in every musical genre of his time.

To commemorate his passing on 14 April 1759 at the age of 74, we decided to celebrate his legacy as one of history’s most towering musical figures.

Halle and Hamburg

George Frideric Handel

Georg Händel was born to a barber-surgeon and his wife Dorothea Taust on 23 February 1685. His father wanted him to take up a legal career, but the boy secretly practiced and received musical training from Friedrich Zachow. When he was not quite 12, his father died and left him with family responsibilities. He briefly enrolled at the University of Halle in 1702 before becoming organist at the Domkirche. He also visited Berlin, where he first encountered opera and the composer Giovanni Bononcini. Inspired, he left Halle for Hamburg in 1703.

Handel joined the city’s independent opera house as a violinist and harpsichordist in 1703, working under Reinhard Keiser’s influence. He befriended Johann Mattheson, with whom he fought a brief duel in 1704, and he began composing when Keiser’s absence created opportunities. His first opera, Almira of 1705, was a success, followed by the less successful Nero. In the event, Handel absorbed Keiser’s eclectic style of blending German, French, and Italian elements, which decisively shaped his future operatic works.

Italy

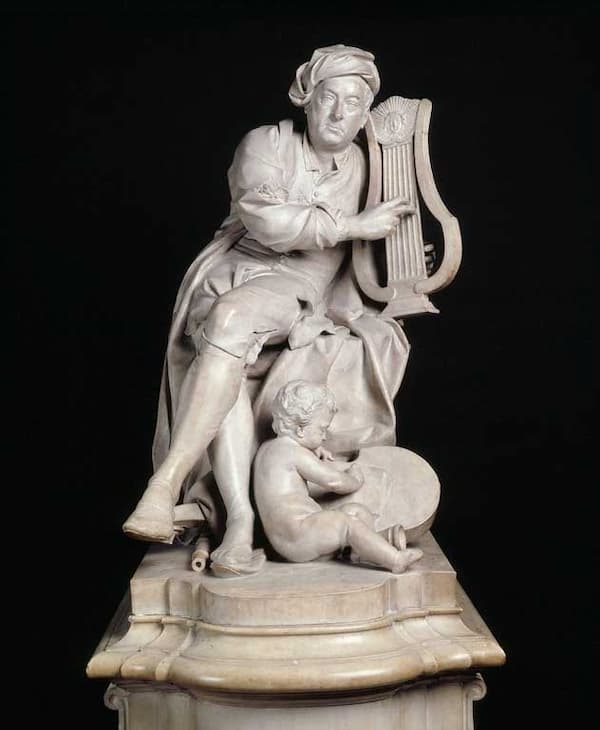

Marble statue of Handel, 1738

While in Hamburg, Handel met visiting musicians who introduced him to Italian music and encouraged him to travel to Italy. Visiting Florence and Venice, Handel arrived in Rome by early 1707 and honed his craft under the influence of composers such as Arcangelo Corelli and Alessandro Scarlatti. His talent quickly earned him the favour of both ecclesiastical and secular princes, and he composed his first opera, Rodrigo, in 1707.

His opera Agrippina, of 1709 triumphed in Venice and solidified his fame with its brilliant arias and dramatic flair. Always the diplomat, Handel navigated elite circles without compromising his independence, and his Italian interlude fuelled his ambition and equipped him with the tools to revolutionise music across Europe. A scholar writes, “Handel’s Italian experience refined his style, blending elegance and dramatic skill, and setting the stage for his later successes.”

Towards London

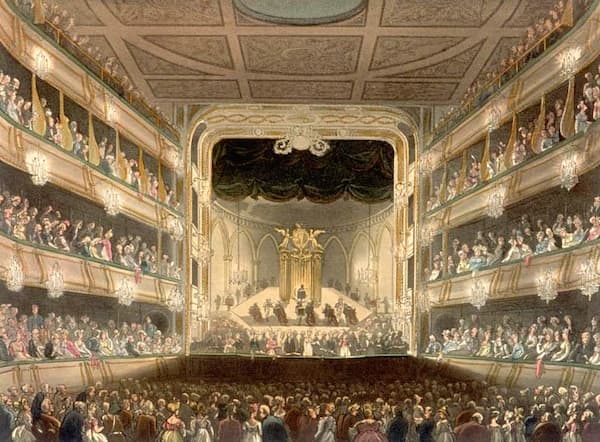

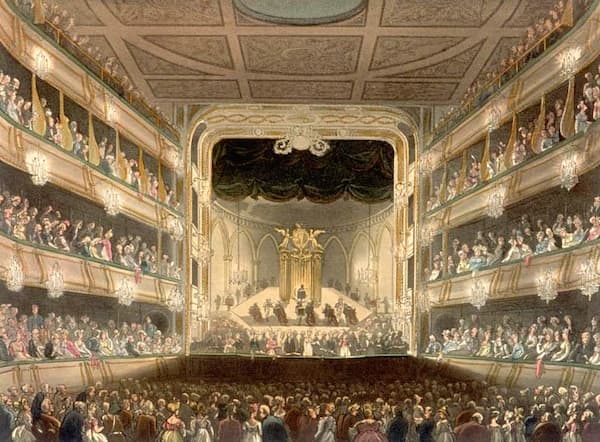

Covent Garden Theatre

Searching for new opportunities, Handel travelled north and arrived in Hanover in 1710, where he was appointed Kappellmeister at the electoral court. He certainly delighted the Electress Sophia and the later King George II with his harpsichord skills. Since his appointment allowed for travel, Handel first arrived in Düsseldorf, and by autumn 1710, he had made his way to London.

Italian opera had taken London by storm, while all-sung English opera faltered as Italian works and singers, particularly castratos became all the rage. The Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket became London’s opera hub, and Handel joined an all-Italian opera company. Rinaldo, his first opera tailored for London, premiered on 24 February 1711. The opera was an immediate success, with contemporary audiences praising “the charms of the music and the splendours of the spectacle.

Cannons

In the summer of 1717, Handel started to work for James Brydges, Earl of Carnarvon, later the Duke of Chandos, at his new mansion, Cannons. During a short but productive period, he composed 11 anthems that, according to scholars, “were unique in English church music.” Significantly, Cannons also saw the completion of the first English oratorio. Esther adapted a biblical drama and reused music from an earlier score.

The Royal Academy of Music

The Royal Academy of Music was founded in February 1719 during Handel’s residence at Cannons. The primary aim was to secure a constant supply of opera seria, with Handel appointed to engage soloists and to initially provide libretti and some arrangements. Handel’s first season at the RAM was a huge success. By staging Rinaldo, Teseo, Amadigi, and Radamisto, he had quickly reached the commanding position he sought.

In fact, Handel considered the aria “Ombra cara” from Radamisto his finest melody ever. And he was closely involved in general administration and the engagement of singers, made decisions on scenery and staging, and rehearsed the orchestra and the singers. The directorate of the Academy, however, did not want to back Handel exclusively, and their choice of resident composer fell to Giovanni Bononcini, who arrived in London in the autumn of 1720.

Operatic Seconds and Covent Garden

Carriera: Portrait of Faustina Bordoni Hasse (1730s) (Museo del Settecento Veneziano, Ca’ Rezzonico, Venice)

Over time, Bononcini’s position gradually weakened, and Handel’s influence boosted. The 1723/24 season saw a resounding triumph of Giulio Cesare, and the masterworks Tamerlano (1724) and Rodelinda (1725) marked the Academy’s artistic peak. However, the arrival of soprano Faustina Bordoni in 1726, rivalling Francesca Cuzzoni, created an atmosphere of animosity, and the RAM collapsed at the end of the 1728/29 season.

Handel was undeterred and quickly started a “Second Academy of Music.” He continued to travel to Italy to engage new singers, and he composed several more operas at home. With the rise of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, Handel also came under attack for being a foreigner. In all, Handel composed about 30 operas for the Royal Academy. Still, when a new theatre at Covent Garden opened in 1732, he shifted operations to the new location for two nights a week.

Oratorio

Francesca Cuzzoni

Handel faced shifting public tastes and financial difficulties in London during the 1730s, as Italian opera seria began to lose favour with audiences. This prompted him to pivot toward a new medium, the English oratorio. Combining his operatic flair with a focus on sacred or dramatic narratives, Handel adapted to the cultural and religious sensibilities of his English audience, who preferred works in their native language and were wary of theatrical excess in religious contexts.

His oratorios, a genre he practically invented, were performed in concert settings without staging or costumes, making them more accessible and cost-effective while still delivering emotional depth and musical grandeur. The rise of the oratorio became a cultural phenomenon, and it revitalised his career. In fact, Handel’s oratorios bridged the gap between sacred music and public entertainment, and thus cemented his legacy as a transformative figure in Western music.

Final Musical Thoughts

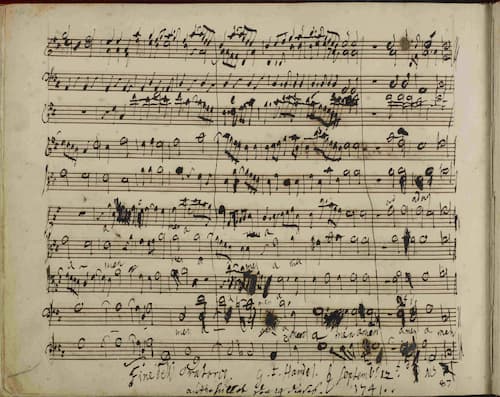

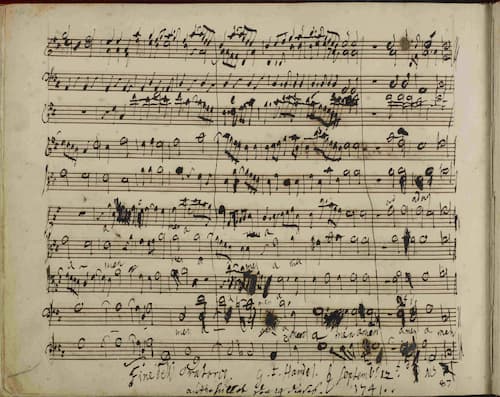

Handel: Messiah – Part III: Amen

Handel continued to refine and expand the oratorio form, producing some of his most enduring and sophisticated works despite facing significant personal and health challenges. After the triumph of Messiah in 1742, Handel’s late oratorios, such as Samson (1743), Belshazzar (1745), Judas Maccabaeus (1747), and Jephtha (1752), showcased his mastery of dramatic storytelling and musical innovation. Although his eyesight began to fail, his creative output remained remarkably robust, driven by his unrelenting passion and adaptability.

His final years were marked by both physical decline and an enduring public presence. After undergoing unsuccessful eye surgeries, he increasingly relied on assistants to notate his compositions, yet he continued to perform, often improvising at the organ during oratorio performances to the delight of the audience. Just days before his death on 14 April 1759, he attended a performance of Messiah at Covent Garden.

Personality, Style and Legacy

As contemporaries report, Handel was a “large, portly man with a sauntering gait and a mix of irascibility, humour, and good-heartedness.” Honest and reliable in financial dealings, he balanced artistic ideals with the needs of individual singers, adapting compositions while showing mixed attitudes toward fellow composers. And a scholar writes, “socially reserved, he enjoyed a private circle, supported charities, and, despite coarse habits like swearing and overeating, was cherished as a genius until retreating into privacy in later years.”

Handel’s music is characterised by its dramatic intensity, melodic richness, and a masterful blend of emotional depth and structural clarity. It displays a remarkable adaptability, consolidating the characteristics of the leading European styles of his day. His works often balance intricate polyphony with straightforward, singable melodies, making them appealing to both sophisticated listeners and broader audiences. Across all genres, Handel’s music is defined by its accessibility, emotional resonance, and enduring versatility.

Handel’s legacy endures, with his contributions influencing generations of composers and performers. Works like Messiah remain cultural touchstones, performed worldwide and cherished for their universal appeal and spiritual depth. Handel’s ability to blend technical brilliance with profound emotion ensures his continued iconic status, equally eliciting scholarly advocacy and the enthusiasm of practical musicians around the world.