by

Composers have been writing violin concertos since the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Over the next three centuries, composers created thousands of violin concertos.

Most have since fallen into obscurity…but a handful have demonstrated their enduring appeal to both musicians and audiences.

© medium.com

Although it’s a fool’s errand to make an objective list of the ten greatest violin concertos, we’re taking a shot at making a subjective one.

So here’s our list of the ten greatest violin concertos, a brief overview of what makes each one so appealing, and a link to the most popular YouTube performance of each concerto.

10. J.S. Bach: Violin Concerto No. 1 (c. 1720)

Johann Sebastian Bach’s first violin concerto likely dates from around 1720, when Bach was employed by Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen.

While working for Leopold, he wrote more instrumental secular music than religious music.

One of the pieces dating from this time was this violin concerto.

It has become one of the most beloved violin concertos of the Baroque era. It features a lively, emphatic first movement; a songful slow movement; and a driving, flowing third movement.

The most-viewed version of the concerto on YouTube is played by German violinist Julia Fischer. It’s light and lovely.

The YouTube heatmap indicates that the most popular part of the performance is at the start of the slow movement at 4:30. Fischer’s playing here is especially luminous.

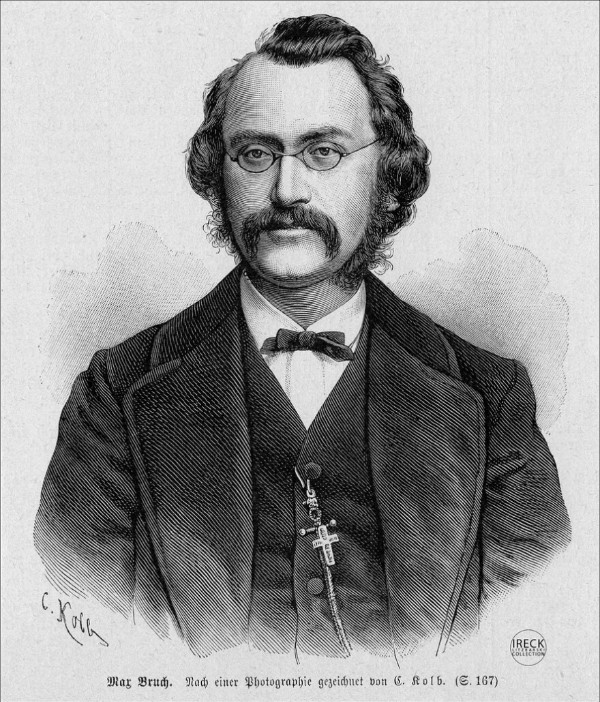

Max Bruch was a prolific German Romantic composer. Unfortunately, he ended up becoming a bit of a one-hit wonder…but that one hit ended up becoming one of the pillars of the Romantic violin repertoire.

After a while, Bruch became exasperated at the concerto’s popularity, which eclipsed so many of his other works:

Max Bruch

“Every fortnight, another [violinist] comes to me wanting to play the first concerto. I have now become rude, and have told them: ‘I cannot listen to this concerto any more – did I perhaps write just this one? Go away and once and for all play the other concertos, which are just as good, if not better.”

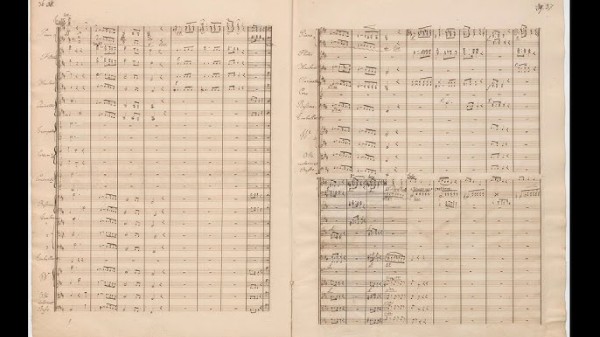

The concerto begins with a slow, theatrical opening marked Vorspiel, the German word for “prelude” or “overture.”

The body of the first movement moves without a break into a warm and placid second movement.

The finale features a triumphant and hummable dance-like theme.

The most popular recording on YouTube is American violinist Hilary Hahn’s performance with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony. The most popular moment in her performance is the stormy second half of the first movement, beginning around 4:45.

Dark, brooding, and painfully personal, Shostakovich’s first violin concerto reflects the composer’s struggles under the oppression of the Soviet rule.

The concerto was written between 1947 and 1948, but Shostakovich knew its style wouldn’t appeal to the conservative tastes of Soviet authorities, so he suppressed it.

It was only able to safely premiere in 1955, two years after the death of Stalin.

It includes a haunting Nocturne, a desperately virtuosic cadenza linking the third and fourth movements, and a fiery finale.

Hilary Hahn once again has the most popular YouTube recording of this repertoire.

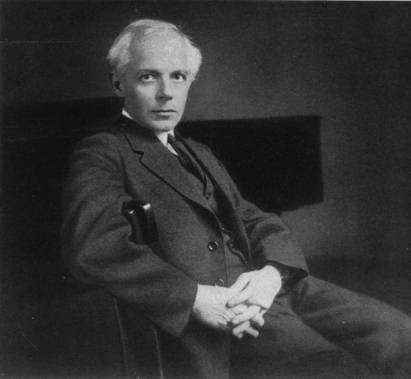

7. Bartók: Violin Concerto No. 2 (1937-38)

Bartók’s second violin concerto is a tour de force of thrilling rhythms and striking colours. It is also one of the most technically demanding violin concertos in the standard repertoire.

Written between 1937 and 1938, this concerto draws heavily on the traditions of Hungarian folk music, while also sounding contemporary and cutting-edge.

Béla Bartók, 1927

Violinist Augustin Hadelich’s performance of this concerto is the most-viewed one on YouTube.

According to the YouTube heatmap, the most popular part of the video is the concerto’s breathless final moments, beginning at 36:00 in this performance. The music sounds like an unhinged folk fiddler has been dropped into the middle of a symphony orchestra.

6. Mozart: Violin Concerto No. 5 (1775)

Unbelievably, Mozart composed all five of his violin concertos while still a teenager. He wrote the first when he was seventeen and the rest when he was nineteen.

Each one shows his musicality growing by leaps and bounds. By the time he wrote the fifth, his technique was completely assured.

This concerto is known for its contrasts and shifts in character. For instance, the opening begins with a cheery tune in the orchestra, but the soloist then enters with a slow, heavenly, operatic sequence of notes before bustling off.

It is nicknamed the “Turkish” concerto due to the percussive segments in the finale, a remnant of the craze for all things Turkish that swept Vienna and western Europe during the late eighteenth century.

The most popular performance of the concerto on YouTube is a 2015 performance by Korean violinist Bomsori Kim at the Queen Elisabeth Competition.

5. Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto (1878)

Tchaikovsky wrote his violin concerto shortly after the breakdown of his six-week-long marriage. (The relationship was doomed because he was gay, and his new wife clearly didn’t understand what she’d gotten herself into.) He fled to Switzerland with a former student/love interest, violinist Yosif Kotek.

Inspired by escaping his traumatic marriage and refreshed by the new surroundings (and company), he wrote his violin concerto in just two weeks.

Although the reaction to the work was initially cool, it has since become one of the most beloved violin concertos ever written.

Yosif Kotek and Tchaikovsky

Violinist Alena Baeva and the Düsseldorf Symphony have created the most-viewed version of the Tchaikovsky violin concerto on YouTube.

The Sibelius concerto is icy, intense, and utterly unique. It is the only violin concerto that Sibelius ever wrote, and is a passionate love letter to his beloved instrument.

He once wrote:

“My tragedy was that I wanted to be a celebrated violinist at any price. Since the age of 15, I played my violin practically from morning to night… My love for the violin lasted quite long, and it was a very painful awakening when I had to admit that I had begun my training for the exacting career of a virtuoso too late.”

Jean Sibelius, 1923

He poured all of his regrets into a deeply emotional violin concerto with a haunting opening, a wistful slow movement, and a finale that has been described as a dance for polar bears.

The most popular performance of the Sibelius concerto on YouTube is one given by Hilary Hahn and the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France in May 2019.

According to the YouTube heatmap, the moment that listeners keep returning to is the final two minutes of the first movement, starting at 17:00. Sibelius’s passion combined with Hahn’s virtuosity is jaw-dropping.

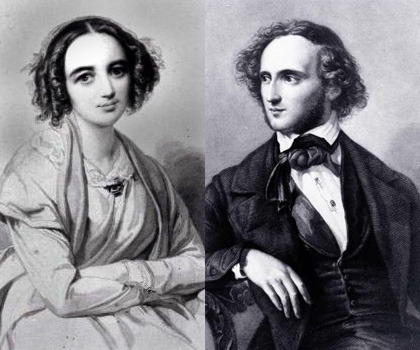

Mendelssohn’s violin concerto is one of the most structurally and technically perfect violin concertos ever written.

It is memorable from the very first measures. The soloist enters almost immediately with a thrilling melody that makes full use of the silvery qualities of the violin’s highest string.

Its flowing melodies, dramatic orchestral interjections, seamless transitions between movements, and fairylike finale have made it a favourite of audiences for nearly two centuries…and it shows no hint of ever going out of style.

Taiwanese-Australian violinist Ray Chen’s performance of the Mendelssohn is the most-viewed performance of this concerto on YouTube. For this elegant 2015 performance, he joined forces with the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra.

Brahms’s violin concerto was written for his dear friend and colleague Joseph Joachim, one of the greatest violinists of his generation.

It is a muscular, monumental work that demands a huge amount of physical and emotional stamina from the soloist.

Joseph Joachim

Another layer of difficulty is that Brahms was not a violinist, so his string writing can be clunky to pull off and make look effortless.

Despite its demands, the radiating warmth and soul-piercing sincerity of this music shine through at every measure, and it has come to be regarded as one of the very greatest violin concertos ever written.

The most popular version of the Brahms concerto on YouTube was performed by Hilary Hahn and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra in March 2014.

There are a few popular moments in this recording, but one of the most popular is Hahn’s powerful entrance at 3:00.

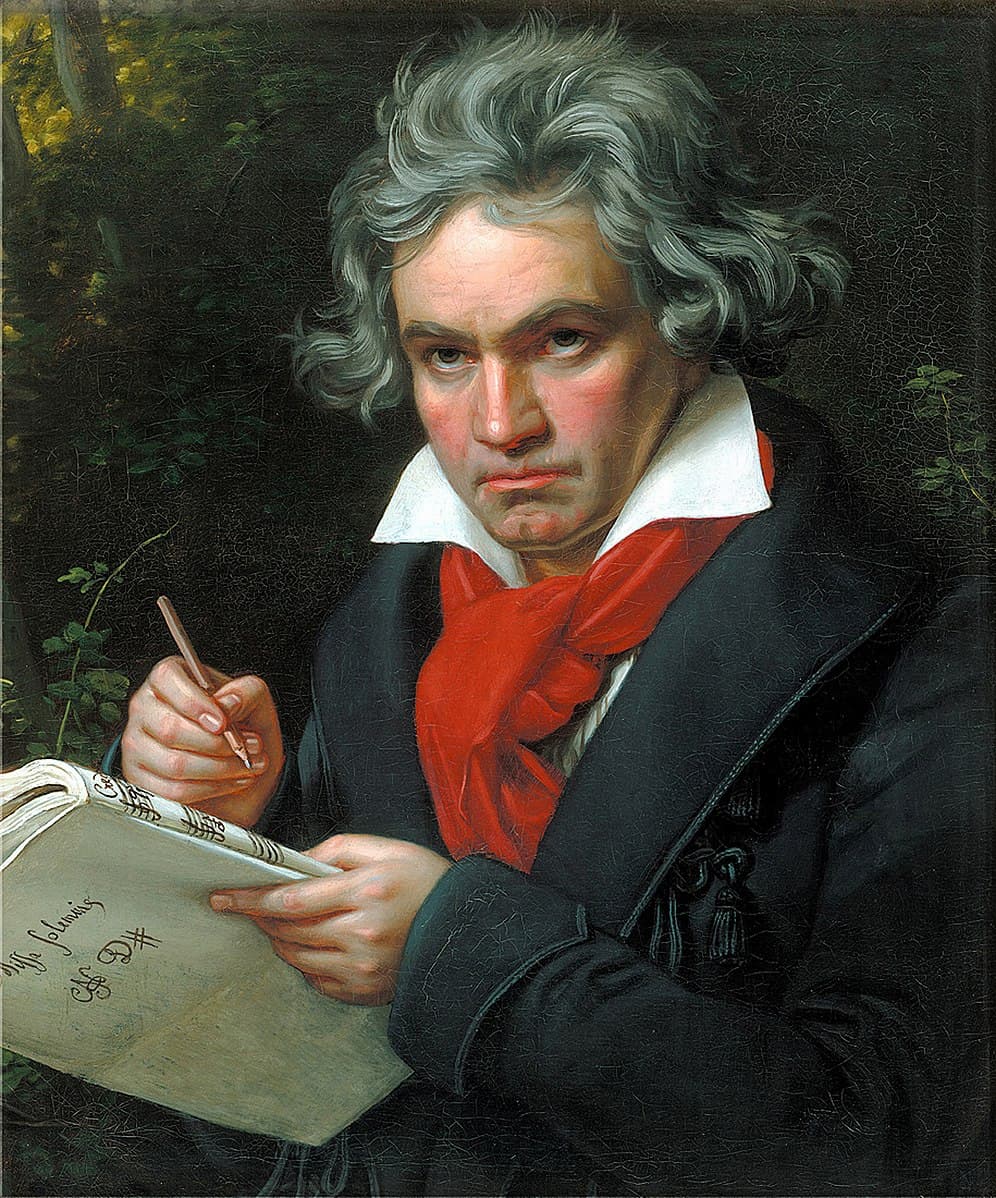

It’s hard to choose the greatest violin concerto, but nobody will criticise you for having the Beethoven concerto at the top of your list.

In this work, Beethoven gives the soloist gorgeous (and incredibly difficult) lyric lines. He also creates an astonishing dialogue between the soloist and orchestra.

The work is on a massive scale: the first movement alone lasts for around twenty minutes. The slow movement is some of the most beautiful music Beethoven ever wrote, and the closing rondo is some of his most joyful and life-affirming.

The most popular performance on YouTube is, once again, one by Hilary Hahn, this time with the Detroit Symphony.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven

Interestingly, the most popular spot in the video is not by Beethoven at all: it’s at 19:45, when Hahn plays a flawless version of Fritz Kreisler’s Beethoven concerto cadenza. Even though modern ears might find it a touch too romantic, it is one of the most famous and beloved violin cadenzas of all time, and an incredible experience to witness being played.

Conclusion

We told you at the start that it’s impossible to choose an objective list of the ten best violin concertos, but this is our best shot at it!

How do you think we did? Which of your favourites did we leave out? And what concerto would be your number one pick