by Emily Hogstadt, Interlude

Today, we’re looking at ten pieces of classical music that reflect on composers’ friendships in some way, whether it’s Beethoven’s dedication of a private string quartet to a friend or Elgar’s extravagant orchestral puzzle dedicated to his friends.

Enjoy!

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet No. 11 (1810-11)

Beethoven’s eleventh quartet was a unique piece from the start: he wrote in a letter to a friend that “The Quartet is written for a small circle of connoisseurs and is never to be performed in public.”

In it, Beethoven allowed himself to experiment and take risks. It was written the year after Napoleon invaded Vienna when the routines of people in the city had been shattered, so there weren’t many audiences interested in coming to performances, anyway.

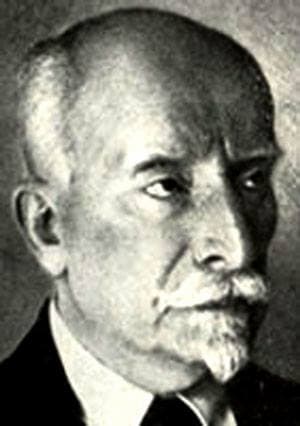

Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz © Wikipedia

Beethoven dedicated this work to his friend, Count Nikolaus Zmeskall von Domanovecz. Zmeskall was a civil servant and an amateur cellist who hosted gatherings in his home where chamber music was performed. These house concerts were the first place where much of Beethoven’s later chamber music was first heard.

Frédéric Chopin: Variations on “Là ci darem la mano” (1827)

Frédéric Chopin had such an intense friendship with political activist Tytus Woyciechowski that some scholars have recently claimed that the two had a romantic relationship.

Tytus Woyciechowski © Wikipedia

Some historians have protested, but regardless of the truth, Chopin certainly did write some very intimate letters to Woyciechowski, including this one in 1830:

I will go and wash. Don‘t kiss me now because I haven‘t yet washed. You? Even if I were to rub myself with Byzantine oils, you still wouldn’t kiss me, unless I compelled you to do so with magnetism. There is some sort of force in nature. Today you will dream that you‘re kissing me. I have to pay you back for the nasty dream you brought me last night…

Three years earlier, Chopin had written a series of variations for piano on an aria from Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni and dedicated it to Woyciechowski.

The two friends eventually drifted apart, but they always remained in each other’s hearts. Woyciechowski eventually named one of his children after Chopin.

Felix Mendelssohn: Allegro Brillant (1841)

Since he was very young, composer Felix Mendelssohn was a close colleague of prodigy pianist Clara Wieck Schumann (the woman who eventually married composer Robert Schumann).

Felix Mendelssohn © U.S. Public Domain

In 1835, Mendelssohn was named music director of the Gewandhaus orchestra in Leipzig. Wieck, born in 1819, was a popular up-and-coming Leipzig-born piano prodigy, so the two often worked together professionally.

As a token of his admiration, in 1841, the year after her marriage to Robert Schumann, Mendelssohn wrote the dazzling Allegro Brillant for piano four-hands for Clara.

As a token of respect for his friend’s ability, the Allegro Brillant is devilishly difficult.

Johannes Brahms: Violin Concerto (1878)

Another musician in the Mendelssohn/Schumann social circle was a Hungarian violinist named Joseph Joachim.

In 1844, at the age of twelve, Joachim gave the first performance in decades of Beethoven’s violin concerto. This performance helped to kick off an entire reappraisal of the work. (By the way, the conductor at that concert? None other than Felix Mendelssohn!)

Joseph Joachim, 1853

When they were young, Joseph Joachim became great friends with pianist Johannes Brahms, and tried to help promote Brahms’s career. In fact, Joachim made the introductions between Brahms and the Schumanns, which became one of the most formative experiences of Brahms’s life.

Brahms and Joachim continued to be friends for many years (although their relationship had its ups and downs).

When Brahms wrote his violin concerto, he wrote it for Joachim, consulting extensively with him via mail. It shouldn’t be a surprise that the finale is extremely Hungarian in character. Joachim reciprocated the friendly gesture by writing the cadenza in the concerto, which is still the only one regularly played.

Edward Elgar: Enigma Variations (1898-99)

When Edward Elgar published his Enigma Variations for orchestra, he included a dedication: “to my friends pictured within.”

Each movement is a portrait of someone in his life, complete with musical puzzles and extra-musical references that have kept musicologists and nerdy listeners debating as to their identities for generations.

In 1911, he expanded on his dedication:

This work, commenced in a spirit of humour & continued in deep seriousness, contains sketches of the composer’s friends. It may be understood that these personages comment or reflect on the original theme & each one attempts a solution of the Enigma, for so the theme is called. The sketches are not ‘portraits’ but each variation contains a distinct idea founded on some particular personality or perhaps on some incident known only to two people. This is the basis of the composition, but the work may be listened to as a ‘piece of music’ apart from any extraneous consideration.

Sergei Rachmaninoff: Piano Concerto No. 2 (1900-1901)

Rachmaninoff’s second piano concerto may be among his most popular works today, but it only came to life after a lot of blood, sweat, and tears…and one especially helpful friend.

Nikolai Dahl © Wikipedia

To make a long story short, Rachmaninoff was so traumatized by the failure of his first symphony in 1897 that it triggered a mental breakdown. He wasn’t sure if he’d be able to compose again.

After several years of writers’ block, in early 1900, Rachmaninoff finally began going to a neurologist and family friend named Nikolai Dahl. Dahl helped him process the failure of his symphony and feel comfortable composing again. In gratitude, Rachmaninoff dedicated his second concerto to him.

The concerto is lush, deeply emotional, and beautifully paced and proportioned. Rachmaninoff toured the world playing and promoting it, ensuring its spot in the classical music canon.

George Enescu: Violin Sonata No. 3 (1926)

In 1926, violinist Franz Kneisel died. Kneisel had had a remarkable career. He was born in Bucharest, Romania, and studied music there and in Vienna. He became a concertmaster when he was just a teenager; he was later handpicked to serve in that position with the fledgling Boston Symphony, and he also founded the first professional string quartet in the United States, the Kneisel Quartet, which performed in America for decades.

Violinist Franz Kneisel in 1902 © Wikipedia

So when Kneisel died in 1926, he was very famous. Composer and violinist George Enescu – a fellow Romanian musician – decided to pay homage to Kneisel’s origins by posthumously dedicating a violin sonata “in Romanian Folk Style” to him. It became Enescu’s most popular work.

Karol Szymanowski: Violin Concerto No 2 (1932-33)

Ukrainian violinist Paweł Kochański became sick with cancer in his forties. Cancer treatments were relatively limited at the time, and he would die at the age of 46 from the disease.

Before he died, however, he commissioned a violin concerto from his friend, Polish composer Karol Szymanowski. Szymanowski was deeply inspired by the request and wrote the concerto in a matter of weeks.

Paweł Kochański © Wikipedia

Happily, Kochański stayed well enough to premiere the work in October 1933 in Warsaw. But his health deteriorated rapidly afterward, and he died a few months later.

Before the score’s publication, Szymanowski edited the dedication to read “A la memoire du Grand Musicien, mon cher et inoubliable Ami, Paweł Kochański” (“In memory of the Great Musician, my dear and unforgettable Friend, Paweł Kochański”).

It ended up being Szymanowski’s last big work, too. He died in 1937 of tuberculosis.

Dmitri Shostakovich: Piano Trio No. 2 (1943-44)

Composer Dmitri Shostakovich began his second piano trio in late 1943 and finished it in August 1944.

While he was working on the trio, in February 1944, a close friend named Ivan Sollertinsky died in his sleep.

Sollertinsky was a brilliant figure who reportedly spoke twenty-six languages (and no, that’s not a typo). Among other things, he helped introduce Mahler‘s music to the Soviet Union.

Understandably, Shostakovich was devastated at the loss, and he wrote that devastating into his haunting piano trio.

According to Sollertinsky’s sister, the trio’s second movement was a portrait of her late brother. It is followed by a tragic dirge.

Arvo Pärt: Für Alina (1976)

There’s a deeply bittersweet real-life story behind Estonian composer Arvo Pärt’s short piano piece Für Alina (or “For Alina”).

In the 1970s, some family friends broke up. The father of the family left for England, and his teenage daughter Alina chose to go with him to see more of the world beyond Estonia.

The work is Pärt comforting his friend, Alina’s mother, while also recognizing her grief at her little girl leaving home.

Conclusion

Classical musicians can certainly be temperamental, but as this overview proves, sometimes the best friendships are friendships based on music!

What are your favorite friendship stories in the history of classical music? What pieces would you add to our list?

.jpg)