It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Sunday, June 2, 2024

Friday, May 31, 2024

Lullaby of Tears Claude Debussy: Berceuse héroïque

by Georg Predota , Interlude

The Battle of the Somme was fought between 1 July and 18 November 1916. One of the largest and most brutal engagements of the First World War, almost one million men were wounded or killed! Among them was the young British composer George Butterworth, who was shot through the head by a sniper in August 1916. Butterworth was one of thousands of well-educated soldiers that chronicled their personal experiences through words, art and music. The writers Robert Graves, JRR Tolkien and Edmund Blunden left a legacy of poetry, memoirs and fiction that helped future generations to understand the reality of war. The same is true for Ralph Vaughan Williams, Gustav Holst and Maurice Ravel.

The Battle of the Somme © dailymail.co.uk

Ravel had hoped to help his country as an aviator, but was considered too old and too short. As such, he served as a driver on the Verdun front, and he memorializes six of his dead friends in Le tombeau de Couperin. Arnold Schoenberg, entirely immersed into his reorganization of traditional tonality, was first drafted into the Austrian Army at age 42. He served for almost a year before a petition for his release was granted. One year later, he was called to active duty again, but given his advanced age, was assigned light duties in and around Vienna.

Claude Debussy © super-conductor.blogspot.com

Claude Debussy, meanwhile, was fighting his own personal battle against colon cancer. He dejectedly wrote, “My age and fitness allow me at most to guard a fence…but, if, to assure victory, they are absolutely in need of another face to be bashed in, I’ll offer mine without question.” Just a couple of years earlier, Debussy had hoped for a quick end to hostilities, but was eventually drawn into a well-organized propaganda campaign protesting the violation of Belgian neutrality by the Germans. King Albert’s Book: A Tribute to the Belgian King and People from Representative Men and Woman Throughout the Word was published in November 1914, and included contributions by Edward Elgar, Jack London, Edith Wharton, Maurice Maeterlinck, among numerous others. Debussy contributed the Berceuse héroïque, a short improvisatory piano piece full of melancholy and discretion that the composer explained “has no pretensions other than to offer an homage to so much patient suffering.”

As the war entered its second year, life for Debussy and his family became a real challenge. Shortages of food and fuel, and a steady escalation of cost made it increasingly difficult to earn a living. “It is almost impossible to work,” Debussy wrote, “to tell the truth, one hardly dares to, for the asides of the war are more distressing than one imagines. I am just a poor little atom crushed in this terrible cataclysm.” Yet, Debussy took heart and began to compose more than he had in years. These works, among them En Blanc et Noir for two pianos, Douze Études composed and dedicated to Chopin, the Sonata for flute, viola and harp and the Cello Sonata are strongly affected by the war. Debussy wrote to a friend, “these works were created not so much for myself, but to offer proof, small as it may be, that French thought will not be destroyed…I think of the youth of France, senselessly mowed down…What I am writing will be a secret homage to them.” The Sonata for violin and piano of 1916/17 was Debussy’s last completed composition, and below his name proudly appeared the telling signature “musicien français.”

Debussy’s last surviving musical autograph, a short piano piece, was presented as a form of payment to his coal-dealer, probably in February or March 1917. The bombardment of Paris as part of a final German offensive commenced on 23 March 1918, two days before Debussy’s death. By that time, the composer was too weak to be carried into the shelter. Yet his perception of war had fundamentally changed. “When will hate be exhausted?” he wrote, “or is it hate that is the issue in all this? When will the practice cease of entrusting the destiny of nations to people who see humanity as a way of furthering their careers?”

Recommended Recordings of Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor, Op. 11

by Ansons Yeung, Interlude

Frédéric Chopin, after a portrait by P. Schick, 1873

© Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

One of the greatest piano concertos ever, Chopin Piano Concerto No. 1 in E minor has long been a cornerstone in the repertoire of many concert pianists. It was actually Chopin’s second piano concerto, as it was written after the premiere of Piano Concerto “No. 2” in F minor. Preceded by trials with a quartet and a small orchestra, the premiere took place in October 1830 at the National Theatre of Warsaw with great success. The concerto enjoyed immediate popularity and remained so up to this day.

As we appreciate this masterpiece, we should imagine ourselves as the 20-year-old Chopin deeply enchanted by his first love, Konstancja Gładkowska, who inspired both of his piano concertos. Chopin wrote to his friend Tytus Woyciechowski, “As I already have, perhaps unfortunately, my ideal, whom I faithfully serve, without having spoken to her for half a year already, of whom I dream, in remembrance of whom was created the Adagio of my Concerto” (referring to his Piano Concerto in F minor). Before Chopin left Warsaw, Gładkowska wrote the following poem in Chopin’s diary to bid him farewell:

Yet while others may

Better appraise and reward you,

They certainly cannot

Love you more strongly than we.

I. Allegro maestoso

Konstancja Gladkowska

The orchestra makes a majestic declaration, followed by the second theme in E major marked cantabile, but the music soon resumes its agitated mood. In fact, the indication maestoso often appears in Chopin’s music, such as in Polonaises Op. 26 No. 2, Op. 53 (“Heroic Polonaise”), Op. 71 No. 1, as well as the first movement of Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor. The piano part presents itself with a powerful, dignified first theme, while the second theme in E major conveys much warmth and intimacy. Later, the second theme appears again but this time in G major, creating a heartrending contrast with the ensuing section with spiralling anxiety and coda, ending in sudden unison in forte.

II. Romanze: Larghetto

The second movement is a breathtakingly beautiful, reverie-like recollection of fond memories, despite the transient turbulence in the middle. In Chopin’s letter to Woyciechowski, he wrote “The Adagio of the new concerto is in E major. It is not meant to create a powerful effect; it is rather a Romance, calm and melancholy; giving the impression of someone looking gently toward a spot which calls to mind a thousand happy memories. It is a kind of reverie in the moonlight on a beautiful spring evening.” There’s probably no better description than this.

III. Rondo: Vivace

While the first two movements were swiftly written, the third movement was completed with some difficulty in August 1830. Full of zeal, vigour and youthful energy, the final movement is based on Krakowiak, a syncopated folk dance from Kraków in 2/4 time. The styl brillant lives up to its full potential with the dazzling passagework, demanding much virtuosity from the soloist. Aside from the technical bravura, the underlying dancing pulse adds even more vivacity to the music. Eventually, the music is brought to a truly triumphant conclusion.

Below are some recommended recordings from me, which are by no means exhaustive!

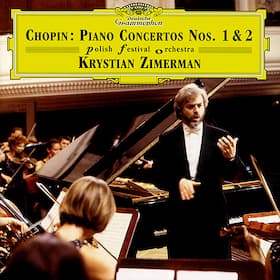

Krystian Zimerman, Polish Festival Orchestra

© Deutsche Grammophon

Zimerman’s unremitting pursuit of perfection is astonishing – hand-picking each of the musicians of the orchestra, meticulously (or obsessively) planning the travel route, accommodation and meals for musicians during the concert tour, rehearsing for painstakingly long hours, etc. The outcome is equally remarkable, to say the least.

Right from the opening of Allergo maestoso, there was immaculate attention to orchestral parts, revealing many nuances that haven’t been heard of previously. Every sound was tastefully sculpted, each phrase scrupulously shaped, with rubato plentiful. Zimerman’s pianism was exceptional as usual – from the luscious tone colours in Romanze to the technical brilliance in Rondo. This is not only a legendary recording of this masterpiece but also of Chopin’s music as a whole.

Bella Davidovich, Sir Neville Marriner, London Symphony Orchestra

Having studied at the Moscow Conservatory under Konstantin Igumnov and Yakov Flier, Bella Davidovich shared the first prize with Halina Czerny-Stefańska in Chopin Competition in 1949. When I encountered this recording, I was immediately struck by the simplicity, naturalness and poetry in her Romanze. Long singing lines were maintained with bel canto by Davidovich, who was known for her singing tone and sensitive touch. It was completely devoid of sentimentality, coupled with a fine balance between classicism and romanticism, which many pianists overlook today. On the other hand, her reading of Rondo, albeit not the most extroverted, had such poise with a natural emphasis on the underlying pulse.

Kyohei Sorita, Andrzej Boreyko, Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra

In my humble opinion, this is the most outstanding rendition in Chopin Competition in 2021. Combining respect for tradition and creativity, Sorita unearthed so many details throughout (especially inner voices from the left hand), which asked for a deep understanding of the score. For instance, listen to his left hand from 9:20 to 9:28, from 14:18 to 14:22, and the inner line from 12:47 to 12:52. Meanwhile, the emotional aspect was never ignored – żal, poignancy, tranquillity and bliss were all distilled into the first movement, while the final movement was filled with ebullience and verve. What a delight!

Manchester Camerata to Host the UK’s First Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia

by Frances Wilson, Interlude

According to the UK’s National Health Service, there are over 940,000 people in the UK with dementia, with 1 in 11 people over the age of 65 being most affected. The care of people living with dementia in the UK costs more than £34bn each year, with the Alzheimer’s Society saying that by 2040, 1.6 million people in the UK will have dementia.

Manchester Camerata’s Music Cafe at the Monastery in Gorton © Duncan Elliott

The Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia is a new collaboration between the Manchester Camerata, a British chamber orchestra renowned for its innovative programming and pioneering outreach work, Alzheimer’s Society, and the University of Manchester. This will continue Manchester Camerata’s existing Music In Mind, a research-based music therapy programme, training a workforce of over 300 volunteer ‘Music Champions’, as well as developing Alzheimer’s Society’s ‘Singing for the Brain’, with the aim to offer musical support to people living with dementia across Greater Manchester. The long-term goal of the Centre of Excellence for Music and Dementia is to analyse how incorporating music into dementia care can reduce the need for intervention from healthcare services, reducing pressure on those services and care staff, as well as improving quality of life for patients, their carers, and families.

© Duncan Elliott

The Camerata’s Music Cafes, which have been running for more than a decade now, will provide support to over 1000 people currently living with dementia in the Manchester area. Created in partnership with the University of Manchester, these music champions use the fundamental principles of music therapy, bringing people living with dementia together to sing songs and perform vocal exercises that help improve brain activity and general wellbeing.

Bob Riley (CEO of Manchester Camerata) and Andy Burnham (Mayor of Greater Manchester) © Jay Cipriani

Speaking at the launch, Mayor of Manchester, Andy Burnham, said that Manchester is “a place that has always understood the power of music” and that the project will “unlock that power more fully and ensure that people everywhere, and in all settings, can benefit. For people living with dementia, who love music, the best thing you can do for them…is to reconnect them with that passion, because in that moment when they recognise that music, they are themselves again.” He highlighted the power of music to create connections: for families where a relative has dementia music can “give them glimpses of the person, and that’s why it’s so precious.” (interview with BBC Radio 3).

© Duncan Elliott

The project’s vital funding, totalling over £1million, will support three years of direct musical support activities across all of Greater Manchester’s 10 boroughs, starting in October 2024.

The project will have major significance in terms of ground-breaking research opportunities, and the intention is that the programme will grow into other areas of the National Health Service and areas of the country, with the hope that other musicians and other orchestras/ensembles may get involved.

“It’s one of the most joyous things any of us have ever experienced. It’s really changed how we view music and what it can do for people.” – Amina Hussain, flautist

Thursday, May 30, 2024

Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You (Orchestral) (Official Video - Netflix’...

LeAnn Rimes - You Light Up My Life - Official Music Video

/ leannrimes

Facebook:

/ leannrimes

Facebook:  / leannrimesmu. .

Twitter:

/ leannrimesmu. .

Twitter:  / leannrimes

/ leannrimes

Monday, May 27, 2024

Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You (Sessions at AOL)

Top 30 Catchiest Songs from Classic Movie Musicals

Bilitis by The Francis Lai Orchestra (13 Days in Japan - Live Tokyo)

Manila Symphony Orchestra | Medley of Philippine Folk Songs

Saturday, May 25, 2024

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1, Op. 23 - Anna Fedorova - Live Concert HD

Friday, May 24, 2024

What Happened to Mozart’s Children?

by Emily F. Hogstad, Interlude

© media-cldnry.s-nbcnews.com

Their courtship had been dramatic. They had started dating the summer of the previous year (after Wolfgang had initially fallen in love with Constanze’s sister). They discussed marriage, but Wolfgang’s father, Leopold, was firmly against it.

Then, in April 1782, they broke up after Constanze had played a parlor game with another young man, during which he measured her calves.

However, after a while, she and Wolfgang made up. In July of 1782, they even moved in with each other…without getting married first!

Constanze Mozart in 1802, portrait by Hans Hansen © Wikipedia

The situation proved scandalous. Wolfgang admitted to his father that they were already sleeping together, so he claimed they had no choice but to get married. Constanze’s mother was beside herself, inquiring whether the police could get involved to rescue her daughter and save her reputation.

Amidst all of this drama, the two did finally get married. The morning after their wedding, Leopold’s extremely reluctant permission arrived in the mail.

The story of Constanze’s pregnancies and their children’s lives offer a unique lens through which to understand Mozart’s biography and music. Today, we’re looking at the six children that Wolfgang and Constanze had together between 1783 and 1791.

Raimund Leopold Mozart (17 June 1783 – 19 August 1783)

On 17 June 1783, around one o’clock in the morning, Constanze Mozart went into labor with her first baby.

While Constanze gave birth, Wolfgang nervously composed two movements of his D-minor string quartet. (Constanze later claimed that the chromatic minuet was inspired by her screams.)

Five hours after Constanze’s labor began, Raimund Leopold Mozart was born: “a fine, sturdy boy, round as a butterball,” Wolfgang reported to his father in a letter the following day.

The Mozarts named the baby Raimund after their landlord. Oddly, their landlord served as the baby’s godfather instead of Leopold. According to Wolfgang, he wanted to call the baby Leopold, but the landlord offered his services as a godparent, and Wolfgang felt helpless to resist. Either Wolfgang was spineless, or it was an attempt to escape his father’s influence.

The Mozarts hired a wet nurse to help care for little Raimund. “Against my wishes and yet not altogether against my will, they brought in a wet nurse for the child!” he reported to his father.

Over the course of the summer of 1783, Wolfgang made plans to visit his father Leopold in his hometown of Salzburg. Wolfgang was leery of leaving Vienna; he was concerned about being arrested, as he’d left his job with the Salzburg archbishop without officially resigning. His father laughed these concerns off and accused his son of just not wanting to see him.

Feeling guilty about Leopold’s jab, he set off with Constanze to Salzburg six weeks after the baby had been born. They left Raimund behind in Vienna (we don’t know why or with whom), choosing not to introduce him to Leopold. Raimund died in mid-August before the visit was over.

We have very little evidence as to how Wolfgang and Constanze handled the death of their firstborn child. Mozart’s sister didn’t mention it in her diaries. A couple of months later, Mozart wrote to Leopold, “We are both very sad about our poor, bonny, fat, darling little boy.” And that’s the last we hear about him in the historical record.

Karl Thomas Mozart (21 September 1784 – 31 October 1858)

Karl Thomas Mozart © Wikipedia

A few months later, around the start of 1784, Constanze got pregnant again. She had Karl Thomas Mozart in September.

Wolfgang died when Karl was seven years old. Later in life, he advanced the theory that his father had been poisoned, although, of course, being just a child, he couldn’t have known if such a thing had really happened.

He went to school in Prague and studied music with Franz Xaver Niemetschek (the first biographer of Wolfgang Mozart) and composer František Xaver Dušek.

When he was twenty-one, he moved to Milan, where he would live for the rest of his life. He tried to make a career in music, but in his mid-twenties he gave up and went into accounting and Italian translating instead.

He earned enough royalties from Wolfgang’s music that he was able to buy a country estate in the township of Valmorea, near Lake Como.

He never got married or had any children, and he died in 1858 at the age of seventy-four.

Johann Thomas Leopold Mozart (18 October 1786 – 15 November 1786)

In 1786, Wolfgang’s big musical project was composing and mounting The Marriage of Figaro, which premiered in May. In January 1787 he went to Prague to conduct a production of it.

In between, Constanze gave birth to their third son, but he died just a month later of “Stickfrais”, which was a term that meant breathing difficulties. It may have been something like whooping cough or lung disease.

Theresia Constanzia Adelheid Friedericke Maria Anna Mozart (27 December 1787 – 29 June 1788)

Just after Christmas 1787, Constanze gave birth to the couple’s first daughter, to whom they gave a very long name. By using the name Maria Anna, they were paying tribute to Mozart’s musician sister, Maria Anna Mozart (also known as Nannerl).

Tragically, their daughter died of intestinal trouble in the summer of 1788. This was the same summer that Mozart wrote his 39th, 40th, and 41st symphonies…a feat that’s difficult to imagine.

Anna Maria Mozart (born and died on 16 November 1789)

In the spring of 1789, when Constanze was pregnant, Wolfgang left Vienna.

He had racked up considerable debt and decided to travel to Dresden, Berlin, and Prague to give concerts to make money. For an entire month after he left, no letters arrived, to Constanze’s great distress.

Wolfgang eventually returned to Vienna, only to find Constanze sick with a leg ulcer. In fact, there was a question of whether she was going to recover. Wolfgang reported in a letter to friends that she was calmly facing her fate, whatever it might be.

Fortunately, she recovered, and after she entered her third trimester, they went to Baden, a spa resort.

Anna Maria Mozart, Wolfgang and Constanze’s fifth child and second daughter, was born in mid-November. She was named after Mozart’s late mother, who had died in 1778. Tragically, she died an hour after she was born. She was baptized before her death and buried the next day.

Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart (26 July 1791 – 29 July 1844)

Karl and Franz Xaver Mozart © Wikipedia

The Mozarts’ final baby, Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart, was born in the summer of 1791. Although he was just an infant when his father died, he ended up being the child who would carry on the Mozart family reputation in the music world. He also inherited the name Wolfgang, which he’d be called by his family.

He was musically talented as a child. Although his older brother believed that their father may have been poisoned, Wolfgang the younger took lessons from Antonio Salieri, who is sometimes named as one of the potential suspects. This is perhaps proof of how unserious his mother took the poisoning rumors. He also studied with Johann Nepomuk Hummel.

Franz Xaver Mozart (1825) by Karl Gottlieb Schweikart

Wolfgang, Jr., made his debut in Vienna in April 1805 at the Theater an der Wien, where Beethoven had given multiple legendary premieres over the previous few years.

He spent most of his career teaching and traveling, performing his own works and the works of his father.

However, he simply wasn’t as talented as his father, and he knew it.

He died a few days after his fifty-third birthday of stomach cancer. His poignant epitaph reads, “May the name of his father be his epitaph, as his veneration for him was the essence of his life.”