It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Friday, September 27, 2024

Learn EVERY Chord and Chord Symbol - The 7 Systems

Heinrich von Herzogenberg - his music and his life

Born: June 10, 1843 - Graz, Austria

Died: October 9, 1900 - Wiesbaden

The Austrian composer, Heinrich von Herzogenberg, was the son of an Austrian Court official. He received his early education in the humanities at the Gymnasien in Feldkirch (Vorarlberg), Munich, Dresden, and Graz. In 1861, he enrolled at the University of Vienna and began a course of study in law and philosophy. This, however, was short-lived, as in 1862 he left the university to become a composition student of Felix Otto Dessoff, a professor at the Vienna Conservatory. Herzogenberg was to study with Dessoff for the next two years. It was at Dessoff's house that Heinrich first encountered Johannes Brahms. The two soon formed a lifelong friendship, with Herzogenberg devoting himself to the promotion of Brahms' music. Although he seems to have valued Herzogenberg's criticism of his own work, Brahms appears to have never found it in himself to take Herzogenberg seriously as a composer. In 1868, Herzogenberg married Elisabeth von Stockhausen (1847-1892), the daughter of a Hanoverian Court diplomat, and a pianist and composer in her own right. Von Stockhausen too shared a close friendship with Brahms, who seems to have valued von Stockhausen 's insights even more than those of Heinrich. It was through the family's interactions with Brahms that the Herzogenbergs came into contact with some of the most notable figures in German music at that time, including Robert and Clara Schumann.

For a period of four years, the Herzogenbergs lived in Graz, where Heinrich worked as a freelance composer. Then, in 1874, they moved to Leipzig where, with Philipp Spitta and several others, Heinrich was to found the Leipzig Bach-Verein (Bach Society). He became the director of the group in 1875, a position he held for the next ten years. In 1885, Herzogenberg was appointed professor of composition at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik, succeeding Friedrich Kiel. From 1889, in addition to his other teaching duties, he also conducted a master class in composition at the Hochschule. It was also in 1889 that Herzogenberg was elected a member of the Akademie and when he began his tenure as director of the Meisterschule für Komposition in Berlin, a position he was to hold from 1889 to 1892 and again from 1897 to 1900. Elisabeth's death, in 1892, seems to have been a heavy blow to Heinrich, who subsequently buried himself in his work. Later that year, he returned to his position at the Hochschule after an absence due to ill heath, no doubt compounded by his grief over the death of his wife. Herzogenberg continued teaching until 1900 when further ill health forced him to retire; he died shortly afterwards.

As a contemporary of Johannes Brahms, Heinrich von Herzogenberg spent most of his compositional life living in the shadow of Brahms' gigantic stature. Herzogenberg's works represent a great divergence in styles and influences. His output is vast and takes the form of every musical genre with the exception of opera. He wrote many concert works with sacred texts, three oratorios; several choral orchestral works, including two psalms, a mass, a requiem, several motets, and a sacred cantata; two symphonies; chamber music including three string quartets; music for piano and organ; many secular part songs (with and without accompaniment for mixed, men's, and women's choirs); and despite being a lifelong Catholic, many short liturgical works for the Protestant liturgy. In general, his music can be said to exhibit a general Brahmsian surface. The piano works in particular, which were initially influenced by Schumann, as well as the chamber music, are clearly modeled on the music of Brahms. However, beneath these surface commonalties, Herzogenberg's music illustrates not only a variety of other influences, but also the hand of a master composer in his own right. In some of his early works, he was intent upon following the path of the "New German School." A later rejection of the "New German" compositional ideology led the young Herzogenberg to a course of study using as a model the music of J.S. Bach. This interest in early music (especially the music of Bach and Heinrich Schütz) was a trait that was greatly fostered by Spitta and took form in Herzogenberg's church music, especially that of the composer's later years.

Works

While Herzogenberg has tended to be characterized as a mere epigone of Brahms, many of his compositions show little or no overt Brahmsian influence, for example his two string trios Op.27 Nos. 1 & 2, while some early compositions pre-dating his acquaintance with Brahms have features in common with the older composer. He wrote much choral, orchestral, instrumental and chamber music, including eight symphonies (one being a programmatic symphony entitled Odysseus). His early Theme and Variations, op.13, for two pianos (1870) is a notable work in its genre. Important works choral include the cantata Todtenfeier, op.80 (1893) in memory of his wife; Mass in E minor, op.97 (1894) in memory of Spitta and the oratorio Die Geburt Christi, op.90 (1894) with a libretto by Spitta’s brother Friedrich. He wrote a great deal of chamber music: 2 string trios Opp.27 Nos 1 & 2, 5 string quartets Opp.18,42 Nos.1-3, & 63, a string quintet (2 violas) Op.17, 2 piano quartets Opp.75 & 95, 2 piano trios Opp.24 & 36, a trio for piano, oboe & horn, Op.61 and several sonatas for various instruments. Today, the general consensus of critics and scholars is that his contribution in this area is his most important.

The Lesbian Diva and Swordswoman!

Julie d’Aubigny aka Mademoiselle Maupin

by Georg Predota, Interlude

When Julie d’Aubigny, born around 1673, first started her singing career at the Marseille Opéra, she quickly fell in love with a young woman. As you might well imagine, the girl’s family was not particularly amused and shipped their daughter to a convent in Avignon. Julie, undeterred, followed her lover into nun hood. When an elderly nun died, the couple stole the body and placed it in the girl’s cell. Then they set fire to the convent to cover their tracks and escaped! As such behavior was generally frowned upon, Julie was charged with kidnapping, body snatching, arson, and failing to appear before the tribunal. The judges could not quite admit to the possibility of one woman abducting another from a convent, and sentenced her in absentia—as a male—to death by fire! What a remarkable story, but who was Julie d’Aubigny, better known as Mademoiselle Maupin?

Mademoiselle Maupin

Julie’s father, an accomplished swordsman, was a secretary to King Louis XIV’s Master of Horse, Count d’Armangnac. He educated his only daughter alongside the boys training as court pages, and Julie dressed as a boy and was easily the best fencer in the group.

At age 14 she became d’Armagnac’s mistress, and she was also quickly married to Sieur de Maupin. Neither husband nor lover held her fascination for very long, so she ran away with a fencing master named Séranne. They made a living from fencing demonstrations at local fairs, and when a spectator refused to believe that she was a woman, she simply took off her blouse! Once they arrived in Marseille, she joined the opera company run by Pierre Gaultier and appeared under her maiden name. She left Séranne for the young woman, and you already know her convent story. Once again on the run, and dressed as a man, she was insulted by the Count d’Albert and quickly fought a duel. Apparently, she drove her rapier through his shoulder, and when she asked about his health the very next day, they became lovers and lifelong friends!

André Campra

Julie’s dream, however, was to become an opera star. As such, she auditioned for the Paris Opéra, was pardoned for her crimes by the King, and by age 17 became a member of one of the world’s greatest musical companies. She appeared in all of the Opéra’s major productions from 1690 to 1694, and achieved lasting musical fame under her stage name “La Maupin.” And she certainly stayed in the limelight with a number of high-profile off-stage scandals. Dressed in men’s clothing, she kissed a young woman at a court ball and was challenged to a duel by three different noblemen. She easily defeated all three, but since duels had been outlawed, she had to flee to Brussels. There, she became the lover of the Elector of Bavaria—who found her entirely too much to handle—and in Madrid she worked as maid to the Countess Marino. Back in Paris, she became infatuated with the soprano Fanchon Moreau, “tried to hill herself, threatened to blow the Duchess of Luxembourg’s brains out, and ended up in court for attacking her landlord.”

In 1703, La Maupin fell in love with the “most beautiful woman in France,” a certain Madame la Marquise de Florensac. According to contemporary accounts, the two women “lived in perfect harmony for two years.” When de Florensac died of a fever in 1705, La Maupin retired from the opera and sought refuge in a convent. She died in 1707 at the age of 33, and one biographer wrote, “destroyed by an inclination to do evil in the sight of her God, and a fixed intention not to, her body was cast upon the rubbish heap.” Théophile Gautier wrote his celebrated novel Mademoiselle de Maupin in 1835, and a number of opera roles were specifically created for her. Among them was the role of “Clorinde” in André Campra’s Tancrède, premiered in Paris in 1702. The plot is set at the time of the Crusades and depicts the tragic love of the Christian knight Tancrède for the Saracen warrior princess Clorinde. In a drama of misunderstandings and impossible love, he ends up killing her in single combat, when she fights him disguised in the armor of another man.” I don’t know about you, but it’s art imitating life, don’t you think?

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764): Seven of His Most Beautiful Instrumental Suites

by Georg Predota, Interlude

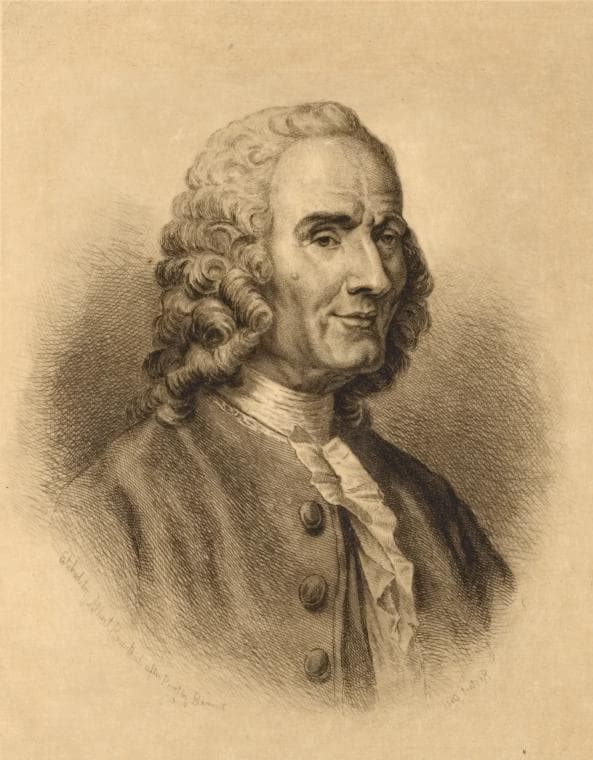

Jean-Philippe Rameau

As a composer, he made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, specifically, to keyboard music. In terms of his dramatic compositions, Rameau is widely considered, alongside with Lully and Gluck, among the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French music. As we celebrate his birthday on 25 September, we thought it might be fun to listen to seven of his most beautiful instrumental suites.

Hippolyte et Aricie

Hippolyte et Aricie

Remarkably, Rameau composed his first opera when he was almost 50, but his catalogue of works eventually grew to more than a hundred separate acts. But what is more, the quality of his dramatic productions established him as one of the greatest opera composers of the Baroque. Following the premier of his first opera, a contemporary composer commented that “there is enough music in it to make ten operas.” Rameau’s music is of the highest quality with great richness and detail, and he was also considered one of great orchestrators of his time.

For his first opera Hippolyte et Aricie of 1733, Rameau selected Abbé Pellegrin as his librettist. The plot is based on Euripides, Seneca and above all Racine’s Phèdre, and it’s a complicated affair. As she believes her husband Theseus to be dead, Phaedra confesses her love for her stepson Hippolytus, who is in love with the young princess Aricia.

When Theseus returns he thinks his son is in love with Phaedra, and asks his father Neptune to send a monster to kill him. Phaedra commits suicide but admits her passion for Hippolytus to Theseus. Hippolytus, who had been believed dead, is saved by Diana and can marry Aricia, while Theseus is condemned never to see his son again.

The dramatic action of the opera is heightened by dance episodes, and these instrumental numbers help Rameau to invent new and more expressive colours. We find a delightful French Overture, and each act features a succession of instrumental pieces. Familiar dances like the rigaudon and the gavotte are interspersed by marches used to introduce characters to the stage, and the Airs unfold in contrasting major/minor or slow/fast pairs.

Zoroastre

Rameau’s Zoroastre costume sketch by Louis Rene Boquet, 1769

Rameau’s Zoroastre of 1749 is supposedly marred by serious defects in the libretto. As a scholar writes, “the conflict of Good and Evil as found in a dualist religion of ancient Persia is weakened by structural flaws and by the introduction of a conventional love element that implausibly involves the great religious Zoroaster himself.” There is plenty of supernatural action as well, and the music is simply awe-inspiring in its power.

Zoroastre, alongside Zaïs, and Les Boréades emerged from the hand of Louis de Cahusac, a playwright for whom the themes of exoticism became more specifically focused on the Middle East. The focus falls on Zoroaster and on the Bactria region, an area annexed by the Persian empire. Although the historical character of Zoroaster had appeared in French opera before, Cahusac was the first author “to make him the central character of an opera.”

The opera was realised using a sophisticated lighting strategy. Act II is bathed in light, while Act IV, which centres on Abramane’s evil incantations, is plunged into darkness. These juxtapositions are clearly heard in the music as the programme to the Overture disclosed. “The first part is a forceful and distressing tableau of Abramane’s barbaric power and the wailing of the people he is oppressing. A gentle calm follows: hope is reborn. The second part is a vivid and joyful picture of the benevolent power of Zoroaster, and of

the happiness of the peoples he has delivered from oppression.”

The remainder of the orchestral suite presents delicate and graceful pieces that include Menuets, and the Airs musically “illustrate the darkness that Cahusac uses to achieve the greatest dramatic and emotional effectiveness during a sacrificial ceremony in which victims are sacrificed using an axe.” And let’s not forget the supernatural scenes which are glorified by dances with music worthy of the best film scores.

Les Paladins

Rameau’s Les Paladins

Rameau’s output touched on virtually all the sub-species of French opera in current use. As we have already seen, he places a heavy emphasis on the tragédie. However, he called Les Paladins a comédie lyrique, suggesting a lighter tone. Les Paladins dates from 1756, and the opera contains number in the Italian style alongside colourful dances and Airs written for the French taste.

In an old castle near a forest, Argie is in love with the paladin Atis. But her guardian Anselme wants to marry her and is holding her and her friend Nérine captive. Nérine tries to charm their jailor Orcan, while Atis and his fellow paladins arrive disguised as pilgrims. When he defeats Orcan, Anselme returns.

Argie confesses her love for Artis to Anselme. He pretends to give his blessing but secretly tells Orcan to kill her. Orcan is reluctant and Nérine, realising Anselme’s plan, again distracts him by pretending she is in love with him. The band of paladins, disguised as demons, give Orcan a beating. While the paladins celebrate their success, Anselme arrives with a group of armed men. Argie and Atis take refuge in the castle, and are saved by the fairy Manto. Manto magically transforms the castle into a Chinese palace and seduces Anselme. Argie can now point to Anselme’s infidelity and he admits defeat. Argie and Atis are reunited and the opera ends with a celebration of their love.

This exciting story elicited some wonderfully lively and colourful musical numbers from Rameau. The overture, with the addition of horns, is a sinfonia in three sections in the Italian style. However, Rameau also included French touches in the slow section. A good many numbers are dances to accompany the on-stage ballet divertissements, and the famous “Air pour les Pagodes” sees the Chinese statues come to life. A spirited Contredanse concludes this wonderful orchestral suite.

Platée

Rameau’s Platée

First performed at Versailles on 31 March 1745, Platée is Rameau’s only comic opera. The occasion for the performance was the wedding of the Dauphin to the Spanish Infanta Maria Teresa. The story is both simple and instantly appealing as it focuses on Platée, a highly unattractive frog-like nymph who inhabits a swamp. She lives under the misapprehension that she is irresistible to men, and that the god Jupiter is in love and wants to marry her.

The entire action is set up in the prologue, including the purpose of the opera, “it is a comedy mocking the folly of man, and the story of a trap set by Jupiter to cure Juno of her jealousy.” Jupiter woos Platée in the form of a donkey, and then an owl. However, the nymph calls on the birds of the marshes and scares Jupiter way.

He returns to declare his love, and as the couple prepares for the wedding, Juno arrives. Furious, she puts an end to the farce and ascends to the heavens with Jupiter. Platée is humiliated and understand that she has been duped, swimming off into the marshes to a chorus of frogs.

The target of that joke might really have been the unfortunate Infanta Maria Teresa, who apparently was not a notable beauty. The music, however, is no joking matter as Rameau’s musical inventiveness and brilliance is heard throughout. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that it was “the most excellent piece of music that has been heard as yet upon our stage.” It features a lively overture and a delicious mixture of airs, choruses and dances that musically portray the intrigue of the roles and characters.

Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s opera-ballet Les fêtes d’Hébé, ou Les talens lyriques (The Festivities of Hebe, or The Lyric Talents) was first performed on 21 May 1739, and featured the famous dancer Marie Sallé. The work consists of a prologue and three self-contained acts loosely based around the lyric arts of poetry, music, and dance. The Prologue takes us to Mount Olympus, where Hebe is sexually harassed by Momus. Cupid suggests she should escape with him to the banks of the River Seine to witness festivities celebrating the arts.

The first entrée is dedicated to poetry, and on the island of Lesbos, the love of the two poets Sappho and Alcaeus is endangered by the jealous Thelemus. He persuades King Hymas to banish Alcaeus, but when the kind is hunting, Sappho stages an allegorical play from him, showing him the truth. The king pardons Alcaeus and the lovers reunite. The second entrée is dedicated to music, and in a temple, Iphise, daughter of the King of Sparta, is ready to marry Tyrtaeus, an accomplished musician as well as a warrior. The oracle announces that Iphise must marry the “conqueror of the Messenians,” and Tyrtaeus leads his soldiers into battle. Tyrtaeus is victorious and the act ends with general rejoicing.

The third entrée devoted to dance is set in a scenic grove and includes an ornate garden. The shepherdess Eglé, well known for her skill at dancing, is due to choose a husband. The god Mercury visits her village in disguise and falls in love with her, arousing the jealousy of the shepherd Eurilas. Eglé chooses Mercury and the two celebrate with the help of Terpsichore, the muse of dance, and her followers.

Rameau was a master of writing dance music; it is full of grace and charm, and an internal sense of movements that provides the perfect vehicle for the expression of Baroque dance movements. It is hardly surprising that Les fêtes d’Hébé was one of his most popular pieces ever, performed over 300 times between its premiere and its final appearance in 1777. If you listen carefully, you will hear the orchestrated music of several harpsichord pieces Rameau had published fifteen years earlier.

Castor et Pollux

Castor and Pollux

According to Thomas Christensen, “Castor et Pollux was generally regarded as Rameau’s crowning achievement, at least from the time of its first revival (1754) onwards.” The story features the famous heroes Castor and Pollux. Although they are twin brothers, Pollux is immortal and Castor is mortal. They are both in love with princess Télaïre, but she loves only Castor.

The twins have fought a war against king Lynceus, which resulted in Castor’s death. The opera starts with his funeral rites, and Télaïre expresses her grief to her friend Phébé. Pollux and his Spartans bring the dead body of Lynceus, who was killed in revenge. Pollux confesses his love for Télaïre, but she avoids a reply. In the end, Pollux renounces his immortality so that his mortal twin might be restored to life.

Robert Mealy writes, “Rameau produces some of the most addictively kinetic music written before Stravinsky. No other Baroque dance music seems so clearly to invite its own choreography.” As the famous ballet-master Claude Gardel admitted, “Rameau perceived what the dancers themselves were unaware of; we thus rightly regard him as our first master.”

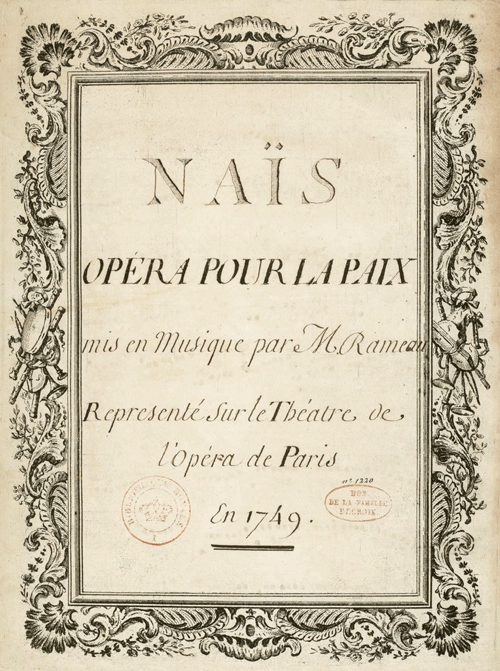

Naïs

Rameau’s Naïs

Rameau composed Naïs on the occasion of the Treat of Aix-la-Chapelle, ending the war of the Austrian Succession. The story tells about Neptune’s love for the nymph Naïs, and he disguises himself as a mortal to try to win her over. Télénus and Astérion are rivals for the affection of Naïs, and her father is a blind soothsayer who warns them to be wary of the sea god. When they attack the disguised Neptune, he drowns them by summoning huge waves. Neptune reveals his identity to Naïs and takes her to his underwater palace, where he turns her into a goddess.

When listening to some of Rameau’s fantastic instrumental suites it is worth noticing the astonishingly inventive orchestral effects created by the most economical means. He draws these special effects from a standard mix of strings and winds, with the colour of the bassoon possibly most striking. A contemporary listener remarked, “Thanks to Rameau, an instrument formerly appreciated only for its force has become pleasant and touching, capable both of pleasing the ear and affecting the heart.”

10 More Dazzling and Awe-Inspiring Piano Quartets

by Hermione Lai, Interlude

As a quick recap, you get a piano quartet when you add a piano to a string trio. The standard instrument lineup for this type of chamber music pairs the violin, viola, and cello with the piano. In its development, the piano quartet had to wait for technical advances of the piano, as it had to match the strings in power and expression.

© serenademagazine.com

Piano quartets are always special because the scoring allows for a wealth of tone colour, occasionally even a symphonic richness. The combined resources of all four instruments are not easy to handle, and the number of works in the genre is not especially large. However, a good many of the extant piano quartets are very personal and passionate statements.

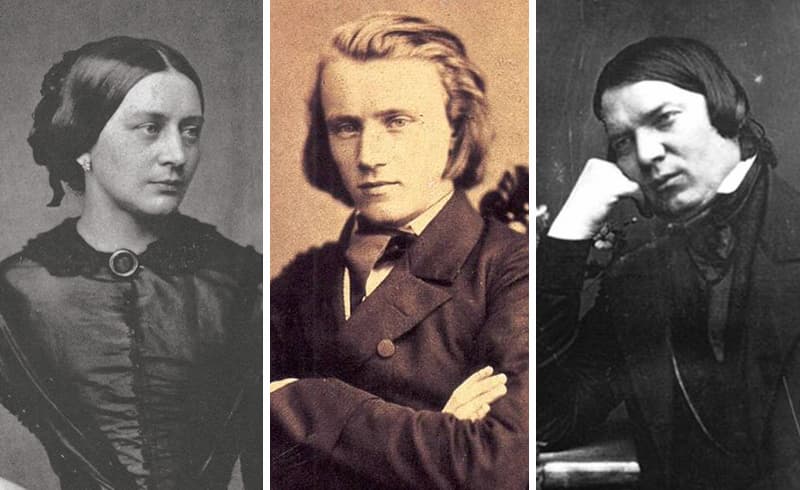

When talking about chamber music, and specifically chamber music with piano, it is difficult to avoid Johannes Brahms (1833-1897). Lucky for us, Brahms wrote three piano quartets, and his Op. 60 took its inspiration from his intense relationship with Clara Schumann. However, it took Brahms almost twenty years to complete the work. The origins date back to around 1855 when Brahms was wrestling with his first piano concerto.

Brahms put this particular piano quartet aside and only showed it to his first biographer in the 1860s with the words, “Imagine a man who is just going to shoot himself, for there is nothing else to do.” Thirteen years later, Brahms took up the work and radically revised it. He probably wrote a new “Andante” and also a new “Finale.” In the end, the work finally premiered on 18 November 1875 with Brahms at the piano and the famous David Popper on cello.

Brahms and the Schumanns

The emotional distress of his relationship with Clara is presented in a mood of darkness and melancholy. A solitary chord in the piano initiates the opening movement, with the string presenting a theme built from a striking two-note phrase. Some commentators have suggested that Brahms is musically speaking the name “Clara” in this two-note phrase. The second theme is highly lyrical but quickly develops towards the dark mood of the opening. The “Scherzo” is also in the minor key, and the deeply felt slow movement is a declaration of love for Clara. The dark opening returns in the final movement, and while the development presents some relief, the work still ends on a note of resignation, albeit in the major key.

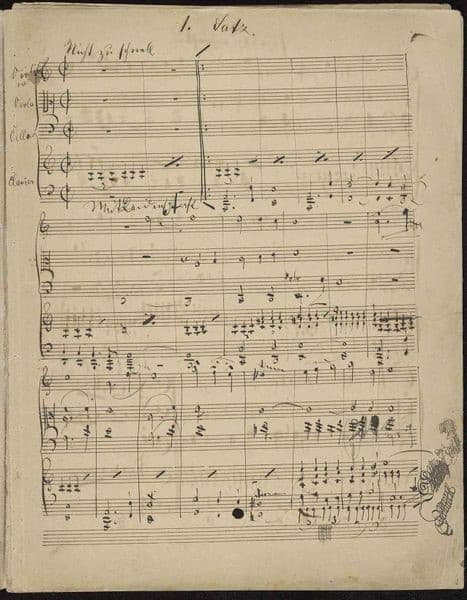

Heinrich von Herzogenberg: Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95

Heinrich von Herzogenberg

The intensely emotional and meticulously crafted compositions by Brahms served as models for a number of composers, among them Heinrich von Herzogenberg (1843-1900). As he writes, “Brahms helped me, by the mere fact of his existence, to my development, my inward looking up to him, and with his artistic and human energy.” While Brahms respected Herzogenberg’s technical craftsmanship and musical knowledge, he never really had anything to say.

Herzogenberg was undeterred and never stopped composing. In 1897, he wrote to Brahms, “There are two things that I cannot get used not to doing: That I always compose, and that when I am composing I ask myself, the same as thirty-four years ago, ‘What will He say about it?’ To be sure, for many years, you have not said anything about it, which is something that I can interpret as I wish.”

A few days before Brahms’ death, Herzogenberg presented him with his probably best and most mature work, the Piano Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 95. The gripping “Allegro” is full of unmistakably Brahmsian character, constructed with compositional economy. An introductory chord develops into the motific core of the entire movement. The “Adagio is full of dreamy intimacy, while the capricious “Scherzo” eventually transports us into a pastoral idyll. Three themes, including a folkloric principle theme, combine in a spirited and temperamental “Finale.”

When Richard Strauss (1864-1949) left college and moved to Berlin to study music at the age of 19, he suddenly discovered a new model in Johannes Brahms. Strauss would meet his current idol personally at the premiere of Brahms’ 4th Symphony in 1885. Under the influence of Brahms, the teenaged Strauss completed his Piano Quartet in C minor in 1884, and a good many commentators believe it to be Strauss’ “greatest chamber work.”

Richard Strauss

Op. 13 is a large work fusing “the sobriety and grandeur of Brahms with the fire and impetuous virtuosity of the young Strauss.” The work opens quietly, and the deceptively simple motif returns in various disguises. However, the music quickly explodes with superheated energy, and its dark sonorities and dramatic scope drive it to a virtually symphonic close.

Finally, the “Andante” introduces a measure of calm, with the piano sounding a florid melodic strain that gives way to a lyrical second subject in the viola. Both themes are gracefully extended while bathing in a delicate and charmed atmosphere. The concluding “Vivace” returns to the mood of the opening movement, and the rondo design also features a serious refrain and a spiky fugato. The work won a prize from the Berlin Tonkünstler, Strauss, however, would say goodbye to chamber music and explore orchestral virtuosity in his great tone poems.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) seems another surprising entry into a blog on the piano quartet. However, a single movement from his student days at the Vienna Conservatory does survive. Mahler took piano lessons from Julius Epstein and studied composition and harmony under Robert Fuchs and Franz Krenn. Mahler left the Conservatory in 1878 with a diploma but without the coveted and prestigious silver medal given for outstanding achievement.

Gustav Mahler’s Piano Quartet

Although he claimed to have written hundreds of songs, several theatrical works, and various chamber music compositions, only a single movement for a Piano Quartet in A minor survived the ravages of time. Composed in 1876 and awarded the Conservatory Prize, it is strongly influenced by the musical styles of Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms.

Conveying a sense of passion and longing, Mahler presents three contrasting themes within a strict formal design. The opening theme possesses an ominous and foreboding character, while the contrasting second—still in the tonic key—is passionately rhapsodic. To compensate for this tonal stagnation, the third theme undergoes a series of modulations. Thickly textured and relying on excessive motivic manipulation, this movement nevertheless provides insight into the creative processes of the 16-year-old Mahler.

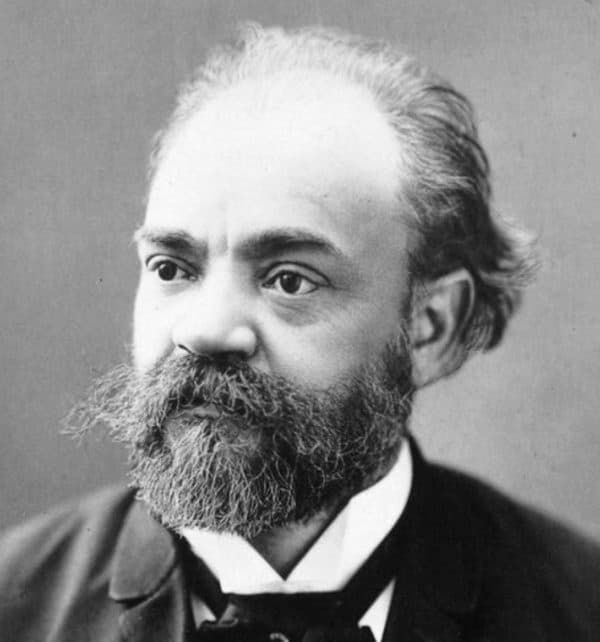

Antonín Dvorák (1841-1904) is another composer who, for a time, took his bearings from Johannes Brahms’s music. Dvorák had always been strongly drawn to chamber music, as his first published works are a string quartet Op. 1 and a string quintet Op. 2.

Dvořák in New York, 1893

Apparently, he composed his D-Major piano quartet in a mere eighteen days in 1875. It premiered five years later, on 16 December 1880. Surprisingly, this piano quartet has only three movements, as the composer combines a scherzo and Allegro agitato in alternation in the Finale. The opening “Allegro” sounds like a rather characteristic Czech melody, initiated by the cello and continued by the violin. By the time the piano takes up the theme, the tonality has shifted to B Major.

The melody of the slow movement, a theme followed by five variations, is introduced by the violin. Dvorák skillfully presents fragments of the theme in various meters and textures. The cello, accompanied by the piano, takes the lead in the final “Allegretto.” After the violin has taken up the theme, the piano takes us into the finale proper.

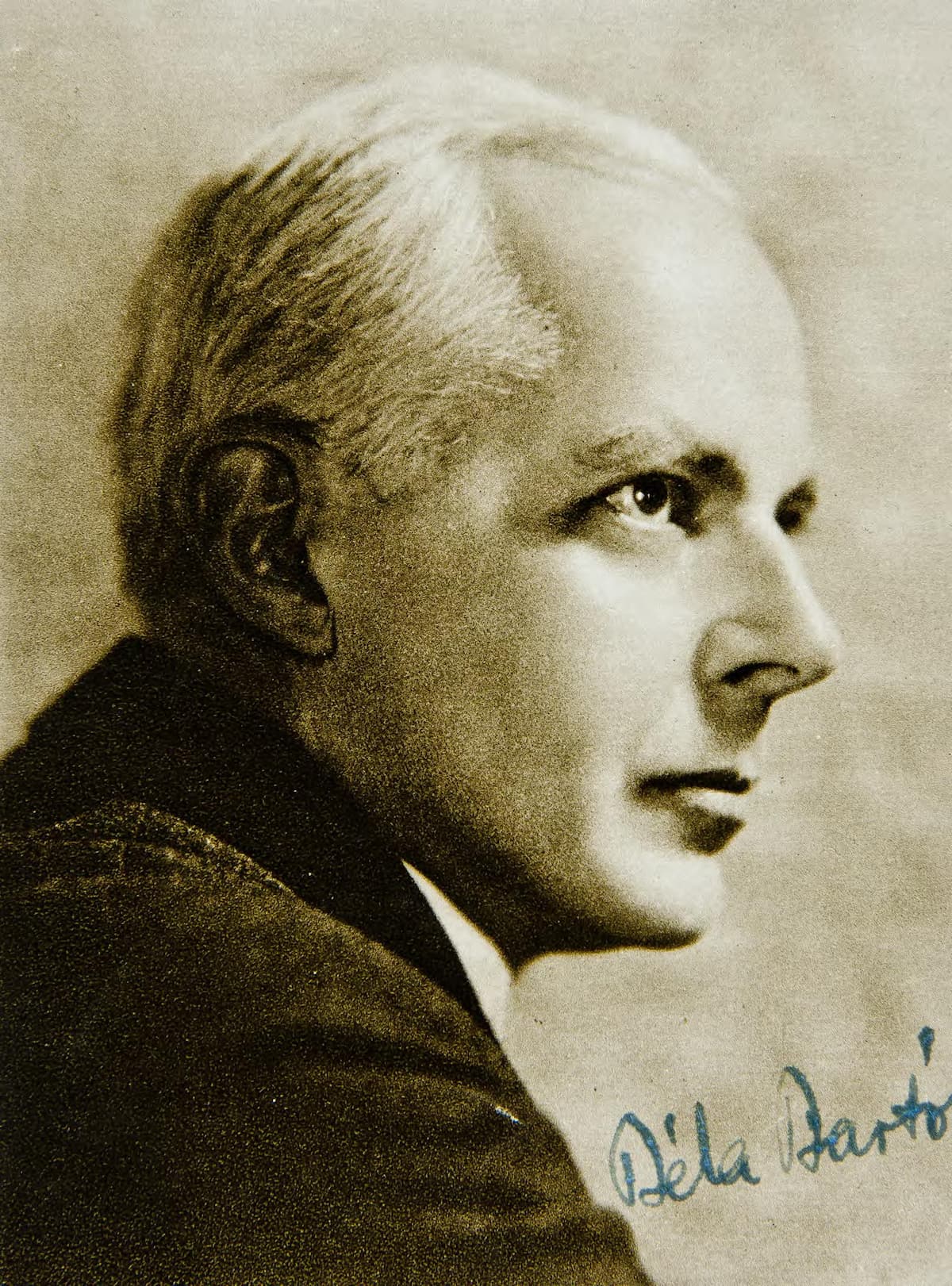

Béla Bartók: Piano Quartet in C minor, Op. 20

Béla Bartók

To his contemporaries and critics, Johannes Brahms looked like a bastion of musical conservatism. Surprisingly, it was Arnold Schoenberg, in his celebrated Radio address entitled “Brahms the Progressive”, who suggested that Brahms was “a great innovator in the realm of musical language and that his chamber music prepared the way for the radical changes in musical conception at the turn of the 20th century.”

Just one year after Brahms’ death, the teenage Béla Bartók (1881-1945) embarked on the composition of a four-movement piano quartet. For years, this score was believed to have been lost, but it was rediscovered by a member of the “Notos Quartet,” who also prepared the edition following the composer’s autograph score. What is more, they also presented a world premiere recording in 2007.

The opening “Allegro” immediately evokes the harmonic and sensuous soundscape of Johannes Brahms. And like his model, Bartók’s musical prose does not follow a predictable pattern as the boundaries and distinctions of theme and development are blurred. Brahms’ rhythmic shapes are the topic of a blazing “Scherzo,” with the “Trio” sounding a sombre lyrical contrast. The “Adagio” sounds like a declaration of love for Brahms, while the “Finale” brims with spicy Hungarian flavours.

Camille Saint-Säens introduced Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) to Pauline Viardot in 1872. Her youngest daughter, Marianne, immediately stole his heart, and Fauré courted her for four painful years. In July 1877, she finally agreed, and the engagement was announced. However, the relationship only lasted until the late autumn of 1877, when Marianne suddenly broke off the engagement.

Pauline Viardot

The exact reasons remain unclear, and Fauré was deeply distressed, with friends reporting that his “sunny disposition took a dark turn.” He started to suffer from bouts of depression, and the Clerc family helped him to recover. At this point, Fauré composed the masterpieces of his youth, among them the piano quartet in C minor.

It might well be considered an early work, however, the composer was already over forty. The opening “Allegro” is pervaded by a sense of optimism, urged on by a strong rhythmical gesture. The E-flat Major “Scherzo” opens with plucked strings and the piano making a light-hearted contribution. The sombre character of the “Adagio” provides an unexpected contrast, and that mood is taken over in the “Finale.” The asymmetrical piano accompaniment continues throughout and brings the work to an emphatic conclusion in the major key.

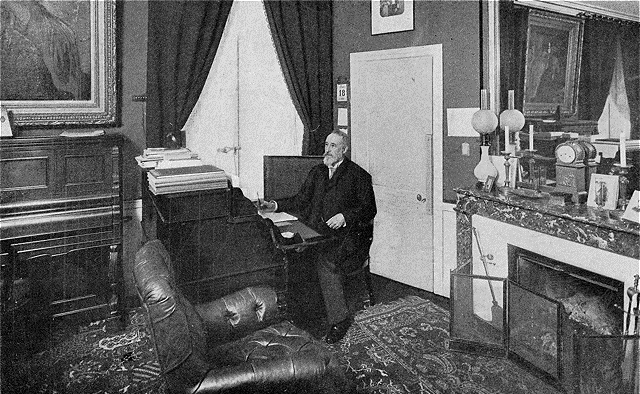

Théodore Dubois: Piano Quartet in A minor

Théodore Dubois in 1905

Théodore Dubois (1837-1924) was highly influential on the French musical scene. Early on, he was known as a composer-organist with a large oeuvre of sacred music to his name. As a pedagogue, he is still famous as the author of the most common music theory textbooks, and as an administrator, he gained notoriety by denying the famed Rome prize to Maurice Ravel on multiple occasions.

Once Dubois retired from the directorship of the Conservatoire, he worked on a chamber music project. A scholar writes, “If they are not progressive works of genius, we can still enjoy their faultless design and beauty of sonority as documents to help us understand the world and spirit in Paris before, around and after 1900.”

Dubois’ piano quartet in A minor appeared in 1907 and features a conventional four-movement design. The opening “Allegro” begins with a cautious drama but quickly transitions to a lyrical melody. The sense of melodic dominance is taken over in the “Andante,” followed by an “Allegro” replacing a scherzo. Essentially a character piece in the style of Mendelssohn, it is followed by a “Finale” of sophistication and balance.

Mélanie Bonis: Piano Quartet No. 1 in B-flat Major, Op. 69

Mélanie Bonis, 1908

Mélanie Bonis (1858-1937) was born into a Parisian lower-middle-class family and initially discouraged from pursuing music. Undeterred, she taught herself how to play the piano, and only at the urging of a family friend and with help from César Franck was she admitted to the Paris Conservatoire.

To conceal her gender during a time when compositions by women were not taken seriously, she shortened her first name to “Mel.” A good many of her late compositions have still not been published, and as she wrote to her daughter, “My great sorrow is that I never get to hear my music.”

Her first piano quartet was written between 1900 and 1905, and stylistically, it is cast in a post-Romantic tradition. Bonis explores the various possibilities of harmony and rhythm, infused with a dash of Impressionism. A good many passages show the influence of César Franck with long developments and rigorous counterpoint. At the work’s first performance, a surprised Camille Sain-Saëns declared, “I would never have believed a woman capable of writing that. She knows all the tricks of the trade.”

Joaquín Turina (1882-1949), together with his friend Manuel de Falla, helped to promote the national character of 20th-century Spanish music. At first, influenced and inspired by Debussy, Turina soon developed a distinctly Spanish style, “incorporating Iberian lyricism and rhythms with impressionistic timbres and harmonies.”

Jacinto Higueras Cátedra: Bust of the composer Joaquín Turina, 1971 (Madrid: Escuela Superior de Canto)

While his Op. 1 Piano Quintet in G minor emerged from his study with Vincent d’Indy, the Op. 67 piano quartet in A minor is “music without the slightest need of any explanations.” The three-movement work is carefully constructed in cyclical form, and “the juxtaposition of contrasting themes give the overall shape a rhapsodic structure.”

The fundamental musical idea is introduced in the opening movement and transformed and modified throughout the work. Of particular lively interest is the central “Lento,” where Turina transformed Andalusian elements without abandoning the gestures, temperament and uniqueness of his native lands. I hope you have enjoyed this further excursion into the realm of the piano quartet, and I can already promise one more article on the subject with music by Mozart, Taneyev, Hahn, Brahms, Copland and others.