by Georg Predota, Interlude

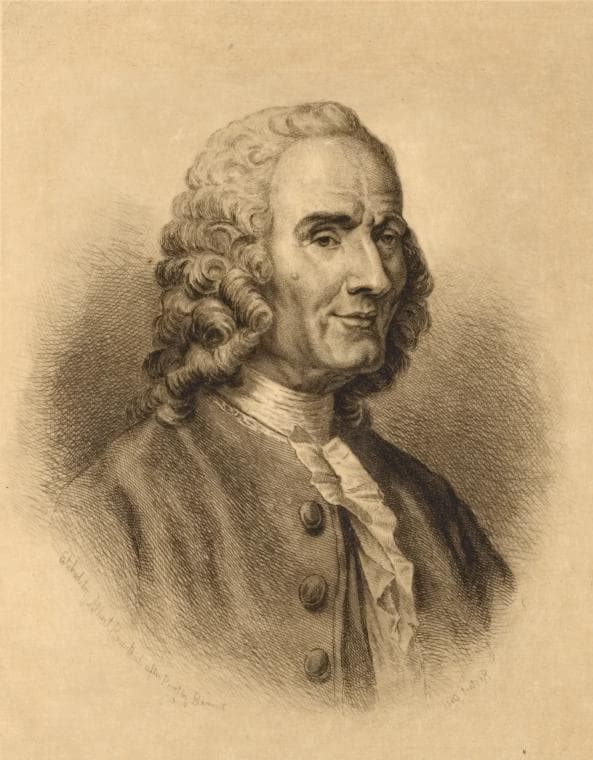

Jean-Philippe Rameau

As a composer, he made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, specifically, to keyboard music. In terms of his dramatic compositions, Rameau is widely considered, alongside with Lully and Gluck, among the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French music. As we celebrate his birthday on 25 September, we thought it might be fun to listen to seven of his most beautiful instrumental suites.

Hippolyte et Aricie

Hippolyte et Aricie

Remarkably, Rameau composed his first opera when he was almost 50, but his catalogue of works eventually grew to more than a hundred separate acts. But what is more, the quality of his dramatic productions established him as one of the greatest opera composers of the Baroque. Following the premier of his first opera, a contemporary composer commented that “there is enough music in it to make ten operas.” Rameau’s music is of the highest quality with great richness and detail, and he was also considered one of great orchestrators of his time.

For his first opera Hippolyte et Aricie of 1733, Rameau selected Abbé Pellegrin as his librettist. The plot is based on Euripides, Seneca and above all Racine’s Phèdre, and it’s a complicated affair. As she believes her husband Theseus to be dead, Phaedra confesses her love for her stepson Hippolytus, who is in love with the young princess Aricia.

When Theseus returns he thinks his son is in love with Phaedra, and asks his father Neptune to send a monster to kill him. Phaedra commits suicide but admits her passion for Hippolytus to Theseus. Hippolytus, who had been believed dead, is saved by Diana and can marry Aricia, while Theseus is condemned never to see his son again.

The dramatic action of the opera is heightened by dance episodes, and these instrumental numbers help Rameau to invent new and more expressive colours. We find a delightful French Overture, and each act features a succession of instrumental pieces. Familiar dances like the rigaudon and the gavotte are interspersed by marches used to introduce characters to the stage, and the Airs unfold in contrasting major/minor or slow/fast pairs.

Zoroastre

Rameau’s Zoroastre costume sketch by Louis Rene Boquet, 1769

Rameau’s Zoroastre of 1749 is supposedly marred by serious defects in the libretto. As a scholar writes, “the conflict of Good and Evil as found in a dualist religion of ancient Persia is weakened by structural flaws and by the introduction of a conventional love element that implausibly involves the great religious Zoroaster himself.” There is plenty of supernatural action as well, and the music is simply awe-inspiring in its power.

Zoroastre, alongside Zaïs, and Les Boréades emerged from the hand of Louis de Cahusac, a playwright for whom the themes of exoticism became more specifically focused on the Middle East. The focus falls on Zoroaster and on the Bactria region, an area annexed by the Persian empire. Although the historical character of Zoroaster had appeared in French opera before, Cahusac was the first author “to make him the central character of an opera.”

The opera was realised using a sophisticated lighting strategy. Act II is bathed in light, while Act IV, which centres on Abramane’s evil incantations, is plunged into darkness. These juxtapositions are clearly heard in the music as the programme to the Overture disclosed. “The first part is a forceful and distressing tableau of Abramane’s barbaric power and the wailing of the people he is oppressing. A gentle calm follows: hope is reborn. The second part is a vivid and joyful picture of the benevolent power of Zoroaster, and of

the happiness of the peoples he has delivered from oppression.”

The remainder of the orchestral suite presents delicate and graceful pieces that include Menuets, and the Airs musically “illustrate the darkness that Cahusac uses to achieve the greatest dramatic and emotional effectiveness during a sacrificial ceremony in which victims are sacrificed using an axe.” And let’s not forget the supernatural scenes which are glorified by dances with music worthy of the best film scores.

Les Paladins

Rameau’s Les Paladins

Rameau’s output touched on virtually all the sub-species of French opera in current use. As we have already seen, he places a heavy emphasis on the tragédie. However, he called Les Paladins a comédie lyrique, suggesting a lighter tone. Les Paladins dates from 1756, and the opera contains number in the Italian style alongside colourful dances and Airs written for the French taste.

In an old castle near a forest, Argie is in love with the paladin Atis. But her guardian Anselme wants to marry her and is holding her and her friend Nérine captive. Nérine tries to charm their jailor Orcan, while Atis and his fellow paladins arrive disguised as pilgrims. When he defeats Orcan, Anselme returns.

Argie confesses her love for Artis to Anselme. He pretends to give his blessing but secretly tells Orcan to kill her. Orcan is reluctant and Nérine, realising Anselme’s plan, again distracts him by pretending she is in love with him. The band of paladins, disguised as demons, give Orcan a beating. While the paladins celebrate their success, Anselme arrives with a group of armed men. Argie and Atis take refuge in the castle, and are saved by the fairy Manto. Manto magically transforms the castle into a Chinese palace and seduces Anselme. Argie can now point to Anselme’s infidelity and he admits defeat. Argie and Atis are reunited and the opera ends with a celebration of their love.

This exciting story elicited some wonderfully lively and colourful musical numbers from Rameau. The overture, with the addition of horns, is a sinfonia in three sections in the Italian style. However, Rameau also included French touches in the slow section. A good many numbers are dances to accompany the on-stage ballet divertissements, and the famous “Air pour les Pagodes” sees the Chinese statues come to life. A spirited Contredanse concludes this wonderful orchestral suite.

Platée

Rameau’s Platée

First performed at Versailles on 31 March 1745, Platée is Rameau’s only comic opera. The occasion for the performance was the wedding of the Dauphin to the Spanish Infanta Maria Teresa. The story is both simple and instantly appealing as it focuses on Platée, a highly unattractive frog-like nymph who inhabits a swamp. She lives under the misapprehension that she is irresistible to men, and that the god Jupiter is in love and wants to marry her.

The entire action is set up in the prologue, including the purpose of the opera, “it is a comedy mocking the folly of man, and the story of a trap set by Jupiter to cure Juno of her jealousy.” Jupiter woos Platée in the form of a donkey, and then an owl. However, the nymph calls on the birds of the marshes and scares Jupiter way.

He returns to declare his love, and as the couple prepares for the wedding, Juno arrives. Furious, she puts an end to the farce and ascends to the heavens with Jupiter. Platée is humiliated and understand that she has been duped, swimming off into the marshes to a chorus of frogs.

The target of that joke might really have been the unfortunate Infanta Maria Teresa, who apparently was not a notable beauty. The music, however, is no joking matter as Rameau’s musical inventiveness and brilliance is heard throughout. Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that it was “the most excellent piece of music that has been heard as yet upon our stage.” It features a lively overture and a delicious mixture of airs, choruses and dances that musically portray the intrigue of the roles and characters.

Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s Les fêtes d’Hébé

Rameau’s opera-ballet Les fêtes d’Hébé, ou Les talens lyriques (The Festivities of Hebe, or The Lyric Talents) was first performed on 21 May 1739, and featured the famous dancer Marie Sallé. The work consists of a prologue and three self-contained acts loosely based around the lyric arts of poetry, music, and dance. The Prologue takes us to Mount Olympus, where Hebe is sexually harassed by Momus. Cupid suggests she should escape with him to the banks of the River Seine to witness festivities celebrating the arts.

The first entrée is dedicated to poetry, and on the island of Lesbos, the love of the two poets Sappho and Alcaeus is endangered by the jealous Thelemus. He persuades King Hymas to banish Alcaeus, but when the kind is hunting, Sappho stages an allegorical play from him, showing him the truth. The king pardons Alcaeus and the lovers reunite. The second entrée is dedicated to music, and in a temple, Iphise, daughter of the King of Sparta, is ready to marry Tyrtaeus, an accomplished musician as well as a warrior. The oracle announces that Iphise must marry the “conqueror of the Messenians,” and Tyrtaeus leads his soldiers into battle. Tyrtaeus is victorious and the act ends with general rejoicing.

The third entrée devoted to dance is set in a scenic grove and includes an ornate garden. The shepherdess Eglé, well known for her skill at dancing, is due to choose a husband. The god Mercury visits her village in disguise and falls in love with her, arousing the jealousy of the shepherd Eurilas. Eglé chooses Mercury and the two celebrate with the help of Terpsichore, the muse of dance, and her followers.

Rameau was a master of writing dance music; it is full of grace and charm, and an internal sense of movements that provides the perfect vehicle for the expression of Baroque dance movements. It is hardly surprising that Les fêtes d’Hébé was one of his most popular pieces ever, performed over 300 times between its premiere and its final appearance in 1777. If you listen carefully, you will hear the orchestrated music of several harpsichord pieces Rameau had published fifteen years earlier.

Castor et Pollux

Castor and Pollux

According to Thomas Christensen, “Castor et Pollux was generally regarded as Rameau’s crowning achievement, at least from the time of its first revival (1754) onwards.” The story features the famous heroes Castor and Pollux. Although they are twin brothers, Pollux is immortal and Castor is mortal. They are both in love with princess Télaïre, but she loves only Castor.

The twins have fought a war against king Lynceus, which resulted in Castor’s death. The opera starts with his funeral rites, and Télaïre expresses her grief to her friend Phébé. Pollux and his Spartans bring the dead body of Lynceus, who was killed in revenge. Pollux confesses his love for Télaïre, but she avoids a reply. In the end, Pollux renounces his immortality so that his mortal twin might be restored to life.

Robert Mealy writes, “Rameau produces some of the most addictively kinetic music written before Stravinsky. No other Baroque dance music seems so clearly to invite its own choreography.” As the famous ballet-master Claude Gardel admitted, “Rameau perceived what the dancers themselves were unaware of; we thus rightly regard him as our first master.”

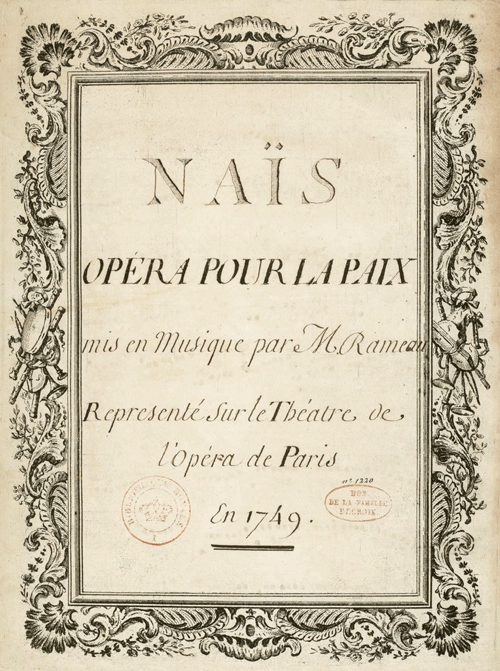

Naïs

Rameau’s Naïs

Rameau composed Naïs on the occasion of the Treat of Aix-la-Chapelle, ending the war of the Austrian Succession. The story tells about Neptune’s love for the nymph Naïs, and he disguises himself as a mortal to try to win her over. Télénus and Astérion are rivals for the affection of Naïs, and her father is a blind soothsayer who warns them to be wary of the sea god. When they attack the disguised Neptune, he drowns them by summoning huge waves. Neptune reveals his identity to Naïs and takes her to his underwater palace, where he turns her into a goddess.

When listening to some of Rameau’s fantastic instrumental suites it is worth noticing the astonishingly inventive orchestral effects created by the most economical means. He draws these special effects from a standard mix of strings and winds, with the colour of the bassoon possibly most striking. A contemporary listener remarked, “Thanks to Rameau, an instrument formerly appreciated only for its force has become pleasant and touching, capable both of pleasing the ear and affecting the heart.”

New from Britannica

New from Britannica