Julie d’Aubigny aka Mademoiselle Maupin

by Georg Predota, Interlude

When Julie d’Aubigny, born around 1673, first started her singing career at the Marseille Opéra, she quickly fell in love with a young woman. As you might well imagine, the girl’s family was not particularly amused and shipped their daughter to a convent in Avignon. Julie, undeterred, followed her lover into nun hood. When an elderly nun died, the couple stole the body and placed it in the girl’s cell. Then they set fire to the convent to cover their tracks and escaped! As such behavior was generally frowned upon, Julie was charged with kidnapping, body snatching, arson, and failing to appear before the tribunal. The judges could not quite admit to the possibility of one woman abducting another from a convent, and sentenced her in absentia—as a male—to death by fire! What a remarkable story, but who was Julie d’Aubigny, better known as Mademoiselle Maupin?

Mademoiselle Maupin

Julie’s father, an accomplished swordsman, was a secretary to King Louis XIV’s Master of Horse, Count d’Armangnac. He educated his only daughter alongside the boys training as court pages, and Julie dressed as a boy and was easily the best fencer in the group.

At age 14 she became d’Armagnac’s mistress, and she was also quickly married to Sieur de Maupin. Neither husband nor lover held her fascination for very long, so she ran away with a fencing master named Séranne. They made a living from fencing demonstrations at local fairs, and when a spectator refused to believe that she was a woman, she simply took off her blouse! Once they arrived in Marseille, she joined the opera company run by Pierre Gaultier and appeared under her maiden name. She left Séranne for the young woman, and you already know her convent story. Once again on the run, and dressed as a man, she was insulted by the Count d’Albert and quickly fought a duel. Apparently, she drove her rapier through his shoulder, and when she asked about his health the very next day, they became lovers and lifelong friends!

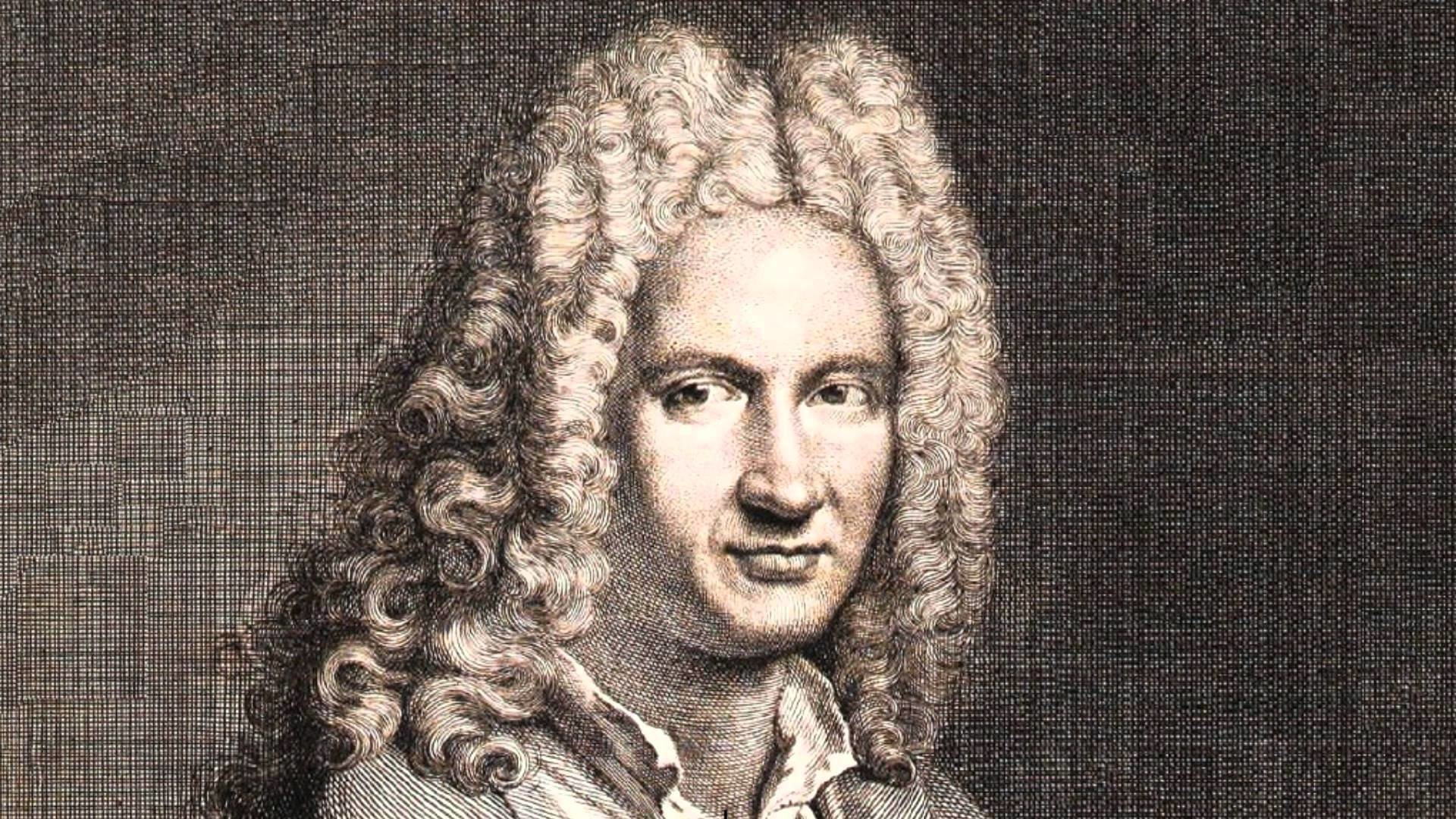

André Campra

Julie’s dream, however, was to become an opera star. As such, she auditioned for the Paris Opéra, was pardoned for her crimes by the King, and by age 17 became a member of one of the world’s greatest musical companies. She appeared in all of the Opéra’s major productions from 1690 to 1694, and achieved lasting musical fame under her stage name “La Maupin.” And she certainly stayed in the limelight with a number of high-profile off-stage scandals. Dressed in men’s clothing, she kissed a young woman at a court ball and was challenged to a duel by three different noblemen. She easily defeated all three, but since duels had been outlawed, she had to flee to Brussels. There, she became the lover of the Elector of Bavaria—who found her entirely too much to handle—and in Madrid she worked as maid to the Countess Marino. Back in Paris, she became infatuated with the soprano Fanchon Moreau, “tried to hill herself, threatened to blow the Duchess of Luxembourg’s brains out, and ended up in court for attacking her landlord.”

In 1703, La Maupin fell in love with the “most beautiful woman in France,” a certain Madame la Marquise de Florensac. According to contemporary accounts, the two women “lived in perfect harmony for two years.” When de Florensac died of a fever in 1705, La Maupin retired from the opera and sought refuge in a convent. She died in 1707 at the age of 33, and one biographer wrote, “destroyed by an inclination to do evil in the sight of her God, and a fixed intention not to, her body was cast upon the rubbish heap.” Théophile Gautier wrote his celebrated novel Mademoiselle de Maupin in 1835, and a number of opera roles were specifically created for her. Among them was the role of “Clorinde” in André Campra’s Tancrède, premiered in Paris in 1702. The plot is set at the time of the Crusades and depicts the tragic love of the Christian knight Tancrède for the Saracen warrior princess Clorinde. In a drama of misunderstandings and impossible love, he ends up killing her in single combat, when she fights him disguised in the armor of another man.” I don’t know about you, but it’s art imitating life, don’t you think?