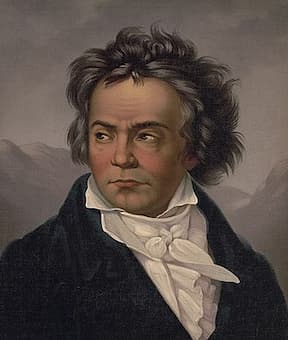

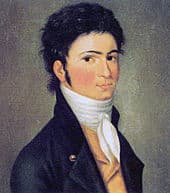

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1818

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was the rising star on the Viennese music scene in the last decade of the 18th century. He made his name by showcasing his talents as a pianist, and he composed and performed piano sonatas of extreme technical difficulty. At the same time he composed music for a variety of musical ensemble and occasions. Ludwig van Beethoven needed to be busy, because he was a freelance musician. In fact, he was the first major composer in that city who did not depend on a fixed musical appointment. However, Beethoven had a dark secret. During his mid-20s, he gradually started to lose his hearing. At first, these periods of temporary hearing loss might not have caused him much concern, as he had suffered from a number of ailments, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and spells of fever since childhood. It seems that he noticed the first symptoms in 1796, or possibly somewhat earlier. In 1815, he told the English pianist Charles Neate that the cause of his hearing loss could be traced back to a quarrel he had with a singer in 1798.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 3 in C major, Op. 2, No. 3

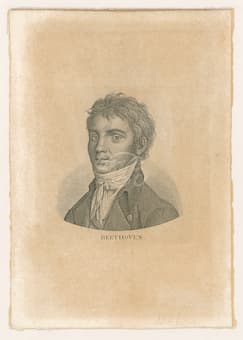

Beethoven, 1800-01

The story goes that a tenor was visiting Beethoven in his apartment. Apparently, they got into a heated argument and the tenor stormed out in a huff. Unexpectedly he returned and knocked on the door. Beethoven is said to have jumped up from the piano angrily to rush and open the door. However, his leg got stuck and he fell face down to the floor. This small accident was not the cause of Beethoven’s deafness, but it triggered a long and continuous hearing loss that would end in almost complete silence. Supposedly, Beethoven said about that particular fall, “I found myself deaf, and have been so ever since.” The hearing loss initially affected mostly his left ear, and as it grew worse Beethoven started to suffer from a severe form of tinnitus. The continued buzzing in his ear made it increasingly difficult to hear music or conversations, and it drove him to the brink of suicide. Beethoven writes, “my ears keep buzzing and humming day and night, and if someone yells, it is unbearable to me.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No.1 in C major, Op. 21

The young Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven continued to perform publically, and he was very careful to not reveal his deafness. He rightly believed that it would ruin his career. He writes, “I don’t hear the high notes of the instruments and voices, and sometimes, I cannot hear people who speak quietly. I can hear the sounds, but not the words. I can with truth say that my life is very wretched. For nearly 2 years past I have avoided all society, because I find it impossible to say to people, ‘I am deaf!’ In any other profession this might be more tolerable, but in mine such a condition is truly frightful. As for my enemies, of whom I have a fair number, what would they say?” In June 1801 Beethoven confides in his Bonn friend F. G. Wegeler, “that the malicious demon, however, bad health, has been a stumbling-block in my path; my hearing during the last three years has become gradually worse.” At that particular time, Ludwig van Beethoven was still hoping that his doctors might be able to help him. He was aware that his hearing loss would present some problems in his professional life, and “what was of equal importance for him, his social life as well.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: String Quartet in C minor, Op. 14, No. 4

Kaspar Anton Karl van Beethoven, Beethoven’s brother

In a letter to his good friend Karl Amenda, Beethoven writes, “Your Beethoven is leading a very unhappy life and is at variance with Nature and his Creator…When I am playing and composing my affliction is hampering me least—it is affecting me most when I am in company.” However, he also reports that Lichnowsky had agreed to pay him an annuity of 600 florins for some years, removing all his financial concerns. His childhood friend Stephan von Breuning had moved to Vienna, and six or seven publishers were competing for each new work. “I often produce three or four works at the same time,” he writes. “My piano playing has considerably improved, and at the moment I feel equal to anything.” Predictably, Beethoven consulted a number of doctors in the hope of finding a cure for his hearing troubles. Initially he looked up Johann Frank, a local professor of medicine. Frank believed that the cause of Beethoven’s hearing loss was related to his abdominal problems. He prescribed a number of traditional herbal remedies that included pushing balls of cotton soaked in almond oil into his ears. Beethoven reports, “Frank has tried to tone up my constitution with strengthening medicines, and my hearing with almond oil, but much good did it do me! His treatment had no effect, my deafness became even worse, and my abdomen continued to be in the same state as before.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Serenade in D major Op. 25

Beethoven’s ear trumpets

Gerhard von Vering was a former German military surgeon and subsequently the Director of the Viennese Health Institute. He was a celebrity doctor, and among his patients was none other than Emperor Joseph II. When Frank’s almond oil treatment showed no healing effect, Beethoven consulted von Vering. He recommended that Beethoven take daily “Danube baths.” Beethoven followed that advice, and sat in tepid baths of river water combined with the ingestion of a small vial of herbal tonic. Apparently, “this treatment miraculously improved Beethoven’s digestive ailments, but his deafness not only persisted, it became even worse.” Beethoven continued to see Dr. von Vering for several months, but he started to protest the increasingly bizarre and unpleasant treatments. It was reported that Dr. Vering strapped toxic bark to Beethoven’s forearms that caused his skin to blister and itch painfully for several days at the time. Beethoven reports to his friend Franz Wegeler in November 1801, “Vering, for the last few months, has applied blisters to both my arms, consisting of a certain bark … This is a most disagreeable remedy, as it deprives me of the free use of my arms for two or three days at a time, until the bark has drawn sufficiently, which occasions a good deal of pain. It is true the ringing in my ears is somewhat less than it was, especially in my left ear where the illness began, but my hearing is by no means improved; indeed I am not sure but that the evil is increased … I am upon the whole much dissatisfied with Vering; he cares too little about his patients.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15

Beethoven, 1801

Dr. Johann Adam Schmidt had also started his medical career as an army surgeon. In 1789 he was appointed Professor of Anatomy in Vienna, and he published a number of important scientific articles. Beethoven implicitly trusted Dr. Schmidt, who recommended leeches and bloodletting as a means of treating the composer’s hearing loss. Dr. Schmidt dejectedly wrote to Beethoven after a number of treatments, “From leeches we can expect no further relief.” Schmidt also recommended for Beethoven to have one of his teeth pulled in hopes of improving the gout-related headache from which Beethoven had been suffering. I am not sure Beethoven heeded this particular advice, but he was clearly interested “in the newest trend sweeping medical science at the time, called galvanism.” That particular treatment involved passing a mild electric current through the afflicted part of the body “as a means of simulating normal bodily activity and aiding the healing process.” Beethoven wrote to a friend, “People talk about miraculous cures by galvanism; what is your opinion? A medical man told me that in Berlin he saw a deaf and dumb child recover its hearing, and a man who had also been deaf for seven years recover his—I have just heard that Schmidt is making experiments with galvanism.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Trio in E-flat major, Op. 38

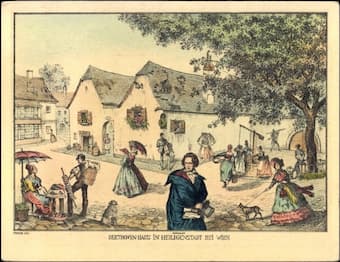

Beethoven’s house in Heiligenstadt

There has been some scholarly debate whether or not Beethoven ever received galvanic treatment. The only known instance comes from an entry in his conversation books from April 1823. Apparently, he conversed with a man suffering from worsening deafness. Beethoven advised, “do not start using hearing aids too soon… Lately, I have not been able to stand galvanism. It is sad. Doctors do not know much, one tires of them eventually.” None of the proposed cures offered any kind of relief, and Beethoven fell into a deep depression. He gradually had begun to realize that his deafness was progressive and probably incurable. Dr. Schmidt finally advised Beethoven to move away from the bustling city and take refuge in the countryside. As such, Beethoven moved to the small town of Heiligenstadt in 1802, at that time located just outside the city limits. Being socially isolated with his hearing further deteriorating, Beethoven wrote a long letter to his two brothers, Carl and Johann, in which he explained his feelings and his condition in great detail, and admitted to having contemplated suicide. He writes, “For six years I have been a hopeless case, aggravated by senseless physicians, cheated year after year in the hope of improvement, finally compelled to face the prospect of a lasting malady whose cure will take years or, perhaps, be impossible.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 17 in D minor, Op. 31 No. 2 “Tempest”

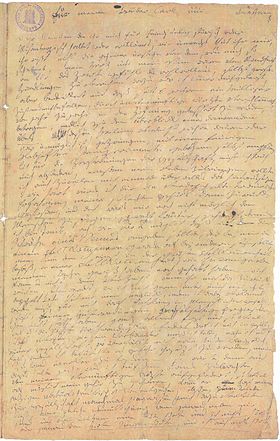

“The Heiligenstadt Testament”

The “Heiligenstadt Testament”, as this letter has become known, continues, “What a humiliation, when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing, or someone heard the shepherd singing, and again I heard nothing. Such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, but little more and I would have put an end to my life. Only art it was that withheld me … and so I endured this wretched existence—truly wretched … It was virtue that upheld me in misery, to it, next to my art, I owe the fact that I did not end my life with suicide. Farewell and love each other. I thank all my friends … how glad will I be if I can still be helpful to you in my grave—with joy I hasten towards death. If it comes before I shall have had an opportunity to show all my artistic capacities, it will still come too early for me, despite my hard fate, and I shall probably wish it had come later—but even then I am satisfied, will it not free me from my state? Come when thou will, I shall meet thee bravely. Farewell and do not wholly forget me when I am dead.”

Ludwig van Beethoven: Violin Sonata No. 7 in C minor, Op. 30 No. 2

Postcard of Beethoven in Heiligenstadt

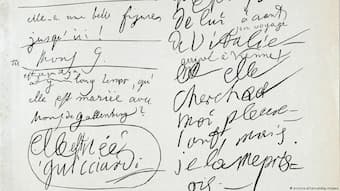

Beethoven never posted that letter, and it was only discovered in his papers after his death. In this famous letter, Beethoven addressed and possibly resolved his inner turmoil. He came to terms with the fact that his hearing would never improve, and it marked a turning point in his life. Beethoven was ready to “seize Fate by the throat; it shall certainly not crush me completely—it would be so lovely to live a thousand lives.” This newly found zest for life was also “brought about by a dear charming girl who loves me and whom I love,” as Beethoven confided in a friend. “For the first time I feel that marriage might bring me happiness. Unfortunately she is not of my class.” This “dear charming girl” was no doubt the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi who had not yet celebrated her 17th birthday. Although she was flattered to receive attention from the famous Beethoven, Giulietta wasn’t inclined to take Beethoven’s devotion very seriously. Beethoven noted on one of his musical sketches, “Let your deafness no longer be a secret—even in art.” Determined to continue living for and through his art, he promised “a completely new way of composing.” This new way is reflected in a series of compositions that reflect or embody extra-musical ideas of heroism.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, Op. 55 “Eroica”

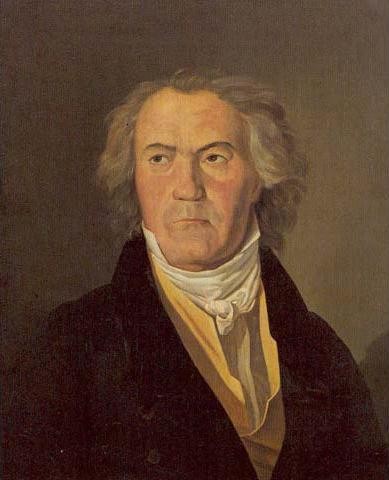

Waldmüller: Beethoven (1823)

While Beethoven was able to compose music, playing concerts, which had been an important source of income, became increasingly difficult. His student Carl Czerny once said that Beethoven could still hear speech and music normally until about 1812. By 1818, however, “Beethoven’s deafness had progressed to such an extent that, with increasing frequency, he began to carry blank books with him, so that his friends and acquaintances, especially when in public, could write their sides of conversations without being overheard, while Beethoven himself customarily replied orally.” Scholars have suggested that Beethoven never became completely deaf, and that he was able to hear muffled words when they were spoken directly into his left ear. Even in his final years, Beethoven was apparently still able to distinguish low tones and sudden loud sound.

Beethoven’s conversation notebook

One day after his death on 27 March, the Institute of Pathology in Vienna performed an autopsy with “specific focus on his ears and the cochlear nerves…” The Eustachian tube was very thickened… and the facial nerves of considerable thickness; the auditory nerves on the other hand shrunken and without pith; the accompanying auditory arteries were of a calibre of a crow-quill, and of cartilaginous consistency. The left auditory nerve, much thinner, arose by three very thin, greyish roots; the right by one root, stronger and pale white… The vault of the skull showed great tightness throughout and a thickness of about half an inch”. Today, physicians are generally in agreement that Beethoven’s deafness was caused by otosclerosis, a condition that exhibits abnormal bone growth inside the ear. In Beethoven’s case, this was accompanied by the degeneration of the auditory nerve. For almost 25 years of his life Ludwig van Beethoven struggled with his severe disability, but his passion for art was all consuming. Music became a mode of self-expression that “transcended the mundane and the narcissistic, as he artistically realized the potential for optimism and idealism within all of us.” Beethoven’s music is an endearing monument to the persistence of the human spirit in the face of adversity.