It's all about the classical music composers and their works from the last 400 years and much more about music. Hier erfahren Sie alles über die klassischen Komponisten und ihre Meisterwerke der letzten vierhundert Jahre und vieles mehr über Klassische Musik.

Total Pageviews

Saturday, September 10, 2022

Friday, September 9, 2022

The Invisible Force: Wind

by Maureen Buja, Interlude

The elements of nature frequently are represented in music: water, snow, and, of course, wind. We looked at a number of different works that might, literally, blow us away. We never see the wind but only the effect of the wind. Composers give us the added dimension of being able to hear the wind.

In Lully’s 1674 opera Alceste, which tells the story of the Queen of Thessaly, Alceste, who has been abducted by the King of Scyros, together with the help of a sea nymphs and Aeolus, the god of winds. The North Wind is summoned to create a violent storm to help the kidnapper get away by sea and arrives with a swoosh.

Following this, the god Éole intervenes to calm the storm by sending the gentle West Wind to disperse the violent North Wind.

Lully: Alceste: The gods, the mortals, and the winds, 1708 (score, Paris, 2nd edition)

One of the common ways to show the winds was to combine them with a storm – we hear this in Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and in Justin Heinrich Knecht’s orchestral work Le portrait musical de la nature (The Musical Portrait of Nature). Written in 1784–85 as a pastoral symphony, the symphony ends the second movement with a gathering of storm clouds and it is in the third movement that the storm breaks, with the wind whistling through the trees, and rain descending in torrents.

For Debussy, in his Préludes, Book 1, the West Wind is violent and savage. Moved from its piano original to the orchestra, the work seems to grow in stature. The title, Ce qu’a vu le vent d’ouest, makes us imagine just what is the West Wind bring with it: a storm and rain beat against a cliff. Nature is unleashed and all we can do is endure.

Storm

The French composer Tristan Murail picks up from Debussy’s vision of the west wind and gives us Dernières nouvelles du vent d’ouest (Latest News from the West Wind). The West Wind strikes France in Normandy and the news it carries from across the Atlantic isn’t always the best.

The Wind in Brittany

French composer Philippe Chamouard sought inspiration for the 1997 work Poème du vent (The Poem of the Wind) in a poem by Oshikhoshi Mitsume, which contrasts the scarlet leaves that are blowing in the wind with the image in the still water of the leaves still on the tree. The music makes the leaves fall downward to float away on the mirroring water.

Red leaves in water

Some composers don’t focus on one wind but invoke the wind from all directions. In his guitar work Si le jour parait… (If The Day Seems…), North African composer Maurice Ohana gives Jeu des quatre vents, the game of the four winds. He also pays tribute to Debussy’s piece to the west wind, by instructing the performer with these directions: Animé, tumultueux, commencez un peu au-dessous du mouvement (Animated, tumultuous, begin a little below the tempo), the same words used by Debussy in his score.

In the fifth of his Six Sonnets for violin and piano from 1922, Catalan composer Eduardo Toldrà invokes a sonnet by the poet Padre Antonio Navarro in his Dels quatre vents (Of the Four Winds). At the beginning of the score, Toldrà gives us the 14-line sonnet that inspired him (‘Dia fervent d’agost era aquell dia…’) invoking a hot day in August, under a serene blue sky, with cicadas singing and two white doves overhead.

The winds blow, sometimes violently and sometimes gently, but always invisibly. We can only see the effect of the wind, not the wind itself.

The Best Classical Music To Listen To While Studying

by Emily E. Hogstad, Interlude

© us.123rf.com/

Whether you’re a newbie or a lifelong connoisseur, all classical music fans agree: some pieces work better as background music than others…especially when we’re studying! A Mahler symphony is powerful in the concert hall, but in the study hall, its grandiosity and mood changes might prove distracting.

So that begs the question: what are the best pieces of classical music to listen to when you hit the books? We all have our favorites, but here are eight of mine. Keep in mind that this is not a traditional list, and many of the pieces here push the boundaries of the traditional definition of “classical music.”

Soundtrack from “Koyaanisqatsi” by Philip Glass. Music written in the minimalist style appears several times on this list. Many people find minimalism’s trademark repeated rhythms, gradual tempo changes, and tonal language helpful to listen to while concentrating. All of these elements are on full display in Philip Glass’ soundtrack for the 1984 experimental film Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance. The music serves as the main aural feature of the film since there is no dialogue. Instead, the story is told through shots of landscapes, military installations, and cities, with Glass’ mesmerizing soundtrack playing for nearly the whole movie.

Sinfoniae Sacrae by Giovanni Gabrieli. Gabrieli was born in the 1550s and died in 1612. Despite the fact that he lived so long ago, there is something fresh and engaging about his compositional language, straddling eras between Renaissance and Baroque. The Sinfoniae Sacrae are rhythmic and upbeat, with just enough contrast to keep things interesting!

Soundtrack from “The Village” by James Newton Howard. “The Village” may not have been a huge box office success, but its haunting soundtrack is transporting, twisting through wistful moods like the view from a kaleidoscope. Superstar violinist Hilary Hahn is a featured soloist, lending the music some serious classical music credentials.

© macleay.edu.au/

Phrygian Gates by John Adams. Phrygian Gates shares important hallmarks with the Glass soundtrack mentioned above. It was written in 1978-79 and features a rhythmic, shimmering solo piano musing away for almost half an hour. As the notes spin, they cycle through a variety of different keys, providing interest. The result is mesmerizing, and perfect for getting into a study groove.

Soundtrack from “The Fountain” by Clint Mansell. Like “The Village” soundtrack, the soundtrack from “The Fountain” may not be classical music strictly speaking, but it does feature well-respected performers from the classical music scene. Members of the Kronos Quartet, an American string quartet that specializes in new music, perform along with the band Mogwai. The result is an overwhelmingly melancholic score that is both dreamy and thought-provoking.

Trois Gymnopédies by Erik Satie. Composer Erik Satie began publishing these three short piano pieces in 1888. They are especially striking for how they balance deep emotion with stasis (a stasis created in large part by the recurring notes in the bass). It comes as no surprise that these deeply affecting pieces have been commandeered for use in modern pop culture, including appearances in movies, orchestral arrangements, and even a Janet Jackson track. They are both calming and inspiring: perfect for studying.

Goldberg Variations by Johann Sebastian Bach. The story of the variations’ conception is legendary. Apparently Count Herman Karl von Keyserling, a diplomat to the Saxon court, had trouble sleeping. The count asked a musician in his service, a keyboard virtuoso by the name of Goldberg, to play harpsichord for him as he battled insomnia. Bach wrote a set of theme and variations for Goldberg to play during these nighttime concerts, and the “Goldberg Variations” were published in 1741. Even if you’re not trying to fall asleep, the Goldberg Variations provide one of the most beautiful backgrounds in all of music.

Anything by Hildegard von Bingen. Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) was many things: an abbess, a philosopher, a mystic, an author, and even a composer. Her music lacks tempo indicators and is monophonic (meaning that it contains only one melody line without accompanying chords). Accordingly, her works sound exceptionally flowing and otherworldly, especially to a modern ear. It is perfect music to explore while studying.

Those are the first eight pieces that come to mind. However, one of the (many!) great things about classical music is that it’s a genre that spans continents and millenia. Eight pieces are just a single drop in an ocean of awesomeness. So dive in yourself and find the pieces that work for you!

Thursday, September 8, 2022

You Are My Everything - Ernesto Cortazar

You Are My Everything - Ernesto Cortazar

37,017 views Aug 15, 2012 Each moment of my life, each note I play, is dedicated to you. Long time ago, my heart became your slave and since then "You are my everything".

Artist: Ernesto Cortazar

Album: Together

Publisher: Piano Drops Music & Publishing

Andrea Bocelli - A Te - Live From Teatro Del Silenzio, Italy / 2007 ft. ...

2,237,162 views Oct 23, 2015 Music video by Andrea Bocelli performing A Te. (C) 2007 Sugar Srl

Watch the Music for Hope full event here: https://andreabocelli.lnk.to/LiveFrom...

Listen to the Music for Hope full event here: https://andreabocelli.lnk.to/MusicFor...

Freddie Mercury & Montserrat Caballé - Barcelona (Live at Ku Club Ibiza,...

Freddie Mercury & Montserrat Caballé - Barcelona (Live at Ku Club Ibiza, 1987)

Tuesday, September 6, 2022

Theme from “The Young and the Restless" (“Lost") — Long Version

Theme from “The Young and the Restless" (“Lost") — Long Version

193,764 views Jul 15, 2021 Provided to YouTube by The Orchard Enterprises

Theme from “The Young and the Restless" (“Lost") — Long Version · Sinfonia of London · Perry Botkin, Jr. · Barry De Vorzon

The Young and the Restless (Original Soundtrack)

℗ 1998 CPT Holdings, Inc., under exclusive license to Madison Gate Records, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Released on: 2021-07-16

Producer: Jack Allocco

Producer: Jez Davidson

Producer: David Kurtz

Music Publisher: Screen Gems-EMI Music, Inc. (BMI)

Auto-generated by YouTube.

Monday, September 5, 2022

Ocean Deep - Cliff Richard (Lyrics) 🎵

🎤 Lyrics:

Love, can't you see I'm alone

Can't you give this fool a chance

A little love is all I ask

A little kindness in the night

Please don't leave me behind

No, don't tell me love is blind

A little love is all I ask

And that is all

Ooh love, I've been searchin' so long

I've been searchin' high and low

And little love is all I ask

A little sadness when you go

Maybe you'll need a friend

Only please don't let's pretend

A little love is all I ask

And that is all

I wanna spread my wings

But I just can't fly

As a string of pearls

The pretty girls go sailin' by

Ocean deep

I'm so afraid to show my feelings

I have sailed a million ceilings

Solitary room

Ocean deep

Will I ever find a lover

Maybe she has found another

And as I cry myself to sleep

I know this love of mine I'll keep

Ocean deep

Now, can't you hear when I call

Can't you hear the word I say

A little love is all I ask

A little feelin' when we touch

Why am I still alone

I've got a heart without a home

A little love is all I ask

And that is all

I wanna spread my wings

But I just can't fly

As a string of pearls

The pretty girls go sailin' by

Ocean deep

I'm so afraid to show my feelings

I have sailed a million ceilings

Solitary room

I'm so lonely, lonely, lonely (Ocean deep)

On my own in my room

I'm so lonely

(Ocean deep)

I'm so lonely, I'm so lonely ...

Time To Say Goodbye - Ernesto Cortazar

Time To Say Goodbye - Ernesto Cortazar

10,185 views Sep 13, 2012 Andrea Bochelli and Sarah Brightman made of this theme a classic and I feel very happy to perform it in this album, I hope you will enjoy it as much as I did.

Artist: Ernesto Cortazar

Album: Masterpieces

Publisher: Piano Drops Music & Publishing

Chamber Music by Women Composers

Röntgen-Maier, La Guerre, Price, Frank, and Pejačević

by Georg Predota, Interlude

Amanda Röntgen-Maier

The violinist and composer Amanda Röntgen-Maier (1853–1894) created a sensation when she became Sweden’s first-ever female Director of the Music at the Conservatory in Stockholm in 1872. Maier decided to continue her private studies in Leipzig with the concertmaster of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, Engelbert Röntgen. She met and became acquainted with Brahms, Joachim, Grieg and Clara Schumann, who greatly admired her. She publically performed many of her own compositions with her future husband Julius Röntgen, son of Engelbert. The married couple moved to Amsterdam, where Amanda spent her time on housekeeping and motherhood. “Her composing faded into the background and her concertizing came to an almost complete halt, as in bourgeois society, public appearances were considered unfitting for a married woman.” In 1886 Röntgen-Maier fell seriously ill, and by the time of her death at the age of 41, she was practically forgotten.

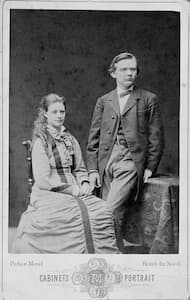

Amanda Röntgen-Maier and Julius Röntgen

During her time in Leipzig she met fellow student Ethel Smyth, and despite their differences in character, they became friends. When Smyth looked back at her time with the Röntgen’s in Leipzig in her memoirs, she wrote, “there was one more belonging to that household, a dear Swedish girl called Amanda Maier, violinist and composer, who afterwards married Julius; an then for the first time I saw a charming blend of art and courtship very common those days.” When she heard of Amanda’s death, she wrote to Julius Röntgen, “I dare not think about how you will endure this—still I envy you in that respect that you have known her better than all the rest of us… It was one of the most beautiful beings that I had ever seen… the only bearable for you must be to know that no human being that has met her will ever be able to rid itself of the impression of her personality.” Röntgen-Maier composed a number of violin sonatas and a concerto for her instrument. The E-minor piano quartet was composed during a trip to Norway in 1891, and it was her final major composition.

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665-1729) was the first woman in France to compose an opera. Born into a family of master masons and musicians, she played the harpsichord and sang at the court of Louis XIV from the age of five. Madame de Montespan kept Élisabeth in her entourage for three years, and her first composition were divertissements intended for court. She married the organist Marin de La Guerre in 1684 and left the gilded world of Versailles for Paris. “She gave lessons and concerts for which she was soon renowned throughout the city.” Élisabeth published her “First book of harpsichord pieces” at the age of twenty-two, but her tragédie lyrique Céphale et Procris, “staged at the Académie Royale de Musique met with disapproval.” She abandoned any other dramatic projects and focused on composing sonatas, a new and highly popular emerging genre.

Élisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre

She was invited to present her work at court, and the sonatas were “played quite perfectly by the Marchand brothers. A contemporary eyewitness reports, “After dinner, his Majesty spoke most obligingly to Mme de La Guerre, and after heaping praise on her sonatas, told her that they were like nothing else. One could offer Mme de La Guerre no higher praise, since these words signified not only that the King had found her music extremely fine, but also that it is original, something that is extremely rare nowadays.” Her sonatas “are conspicuous for their variety, rhythmic vigour and expressive harmony, as well as for certain innovative features in the violin writing.” Inspired by her sonatas alternate between Italian and French idioms. “The former is present in the expressive opening movements, the incisive rhythms and the fugal sections of the fast movements. The composer remains true to the French aesthetic in the dances featured in some of the sonatas, the use of the viol as a solo instrument, and the melodic vein of the arias.”

Florence Price

In 1943, Florence Price (1887-1953) wrote a letter to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky in which she referred explicitly to her two handicaps. She told him that “music written by women in general are preconceived by many to be light, froth, lacking in depth, logic and virility, and that she wanted her music to be judged on merit alone.” Price felt that she suffered from a second affliction, her race as an African American. Price was actually of mixed racial heritage, African, European and Native American. Her mother was worried that “anything pertaining to a black racial identity would preclude her daughter’s success. As such, she encouraged her daughter to present herself as Mexican.” Price nevertheless made history when the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Frederick Stock premiered her award-winning Symphony in E minor in 1933. Critics raved about the premiere and “hoped that this would bring about a new era, one where the concert hall would finally welcome black classical artists.”

Florence Price at the piano, University of Arkansas

Price was celebrated during her time, but she continued to face gender and race barriers. At the time of her death, the majority of her music remained unpublished, “and a significant quantity of her manuscripts had disappeared without trace. It was not until 2009 that a cache of them, including two lost symphonies, was discovered by property developers in the attic of an abandoned house in Illinois.” That cache included a Piano Quintet in A minor with an inscription added by Price in 1952. However, musicologists have suggested that the “work might have been written around 1936, the date of her well-known E-minor quintet.” Written in a late-romantic idiom, “the piece celebrates African American heritage by echoing the musical language of spirituals and hymns (second movement), and reworking elements of the popular juba stomping dance that hailed from the slave plantations of the Deep South (third movement).” The A minor Quintet was first published in 2017.

Gabriela Lena Frank

Born in 1972 in Berkeley, California, Gabriela Lena Frank, daughter to a mother of mixed Peruvian/Chinese ancestry and a father of Lithuanian/Jewish descent, explores her multicultural heritage through her compositions. Taking inspiration from the fieldwork of Bela Bartók and Alberto Ginastera, Frank has travelled extensively throughout South America and “her pieces reflect and refract her studies of Latin-American folklore, incorporating poetry, mythology, and native musical styles into a western classical framework.” Frank has been nominated for Grammys as both composer and pianist, and she holds a Guggenheim Fellowship and a USA Artist Fellowship given each year to fifty of the country’s finest artists. Her work has been described as “crafted with unselfconscious mastery,” “brilliantly effective,” “a knockout,” and “glorious.” She is a member of the Silk Road Ensemble and receives regular commissions from Yo Yo Ma, the Kronos Quartet and a host of leading orchestras.

Identity is always at the center of Frank’s music, and as a musical anthropologist she travels extensively through South America. She writes, “there is usually a story line behind my music, a scenario or character.” Such is certainly the case in her Leyendas (Legends): “An Andean Walkabout.” Composed in 2001, she explains “An Andean Walkabout for string quartet, later arranged for string orchestra, draws inspiration from the idea of mestizaje as envisioned by the Peruvian writer José María Arguedas, where cultures can coexist without the subjugation of one by the other. As such, this piece mixes elements from the western classical and Andean folk music traditions.” Frank incorporates a wide variety of Andean instruments, a legendary runner from the Inca period, professional crying women, and a flirtatious love song sung by “romanceros.”

Dora Pejačević

Dora Pejačević (1885–1923) was born in Budapest, but grew up in her ancestral Croatia. Her mother was a Hungarian countess, “a woman of great beauty who was a trained singer, played the piano and was a fine amateur painter.” Dora was educated by a private English governess, and she was fluent in several languages. She taught herself to play the piano and her early compositions paved the way for her study abroad. She attended the Croatian Music Institute in Zagreb, and also took lessons in Dresden and in Munich. However, in musical terms she was largely self-taught, “which is remarkable considering the inventiveness, rich brilliance and enduring quality of her compositions.” She composed her first orchestral work, a piano concerto in 1913, and part of her Symphony was first presented in Vienna in 1918, and subsequently performed in full in Dresden in 1920. Dora married the military officer Ottomar von Lumbe in 1921, and three months before the birth of their son Theo she wrote, “I hope that our child should become a true, open and great human being—prepare its way for it, never prevent it from knowing in life that suffering ennobles the soul because only in that way can one become a human being.” Her portentous words sadly proofed prophetic, as Dora died in Munich in 1923, at the incredibly young age of 38.

Pejačević Hall

Her compositions including songs, piano works, chamber music and several works for large orchestra follow a late Romantic idiom, “enriched with Impressionist harmonies and lush orchestral colours.” In her music Pejačević always strove to break free “from drawing-room mannerisms and conventions,” and she introduced the orchestral song into Croatian music. “Her work concurred with the modernist movement in literature and the secession in the visual arts; without breaking new ground she helped to bring a new range of expression into the traditional musical language.” Much of her music has yet to be published and recorded, but the Croatian Music Information Center holds her 57 known compositions as a single collection, and they have published a number of her larger scores. Indeed, there is newly-found interest in Pejačević as her life became the subject of the fictionalized film “Countess Dora.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)