by Hermione Lai , Interlude

Erard piano, c. 1830

Virtuosity is totally intoxicating. To me, there is nothing ambivalent in a performance of a piece of music of such complexity that only the most exceptional artists can tackle it. It’s like an athletic event of the most demanding physicality, and in the case of musical performance, at the highest level of craftsmanship and artistic skill. It was the violinist Niccolò Paganini who first personified the exciting concept of virtuosity. He could extract sounds and effects from his instrument that nobody had been able to imagine. Paganini was capable of such virtuosity that otherworldly powers were ascribed to him. Contemporaries had no qualms suggesting that Paganini had made a pact with the devil. When Franz Liszt heard him in performance, he decided to equal Paganini’s skill on the piano. Liszt’s quest was aided by a piano of better mechanical opportunity and greater dynamic range supplied by the instrument builder Érard.

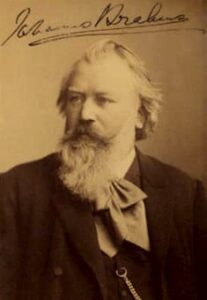

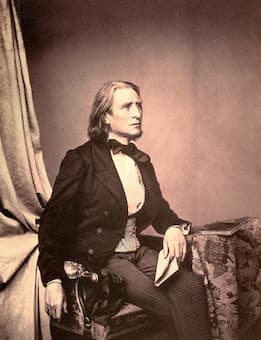

Franz Liszt

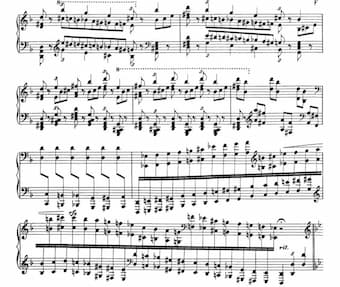

Érard introduced the so-called repetition mechanism, which allowed for more rapid repetition and at the same time increased sensitivity to key touch, which enhanced the possibilities for musical expression. Paris became the center of piano building and virtuoso performance, with “dozens of steel-fingered, chromium-plated virtuosos playing there, including Kalkbrenner, Herz, Hiller, Hünten, Pixis, Thalberg, Dreyschock, and Cramer… There was Dreyschock with his octaves and Kalkbrenner with his passage-work, and Thalberg with his trick of making two hands sound like three.” Heinrich Heine ranked the mightiest piano virtuosos, calling “Thalberg a king, Liszt a prophet, Chopin a poet, Herz an advocate, Kalkbrenner a minstrel, Mme Pleyel a sibyl, and Döhler a pianist.” The cult of the piano virtuoso was exploding in Paris, and as they attempted to outperform each other, etudes of staggering difficulties started to appear. In this blog, we will listen to a brief survey of mind-boggling etudes from the planet impossible.

Liszt: Transcendental Etudes No. 4: ‘Mazeppa’

Franz Liszt was the undisputed superstar, and his performance style was described as “containing abandonment, a liberated feeling, but even when it becomes impetuous and energetic in his fortissimo, it is still without harshness and dryness. He draws from the piano tones that are purer, mellower and stronger than anyone has been able to do; his touch has an indescribable charm.” The reviewer doesn’t actually focus on pianistic pyrotechnics, but on his delicate touch and charm, and “even his handsome profile.” Apparently, Liszt’s performances induced fainting spells among female listeners, which were subsequently dubbed “Liztomania” by Heinrich Heine. This “Liszt-Fever,” as it was called, was thought to have been a medical condition that was extremely contagious.

Franz Liszt, 1858

Heinrich Heine offered an alternate explanation. “A physician, whose specialty is female diseases, and whom I asked to explain the magic our Liszt exerted upon the public, smiled in the strangest manner, and at the same time said all sorts of things about magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of the contagion of the close hall filled with countless wax lights and several hundred perfumed and perspiring human beings, of historical epilepsy, of the phenomenon of tickling, of musical cantharides, and other scabrous things, which, I believe have reference to the mysteries of the Bona Dea (An ancient Roman goddess associated with chastity and fertility). Perhaps the solution of the question is not buried in such adventurous depths, but floats on a very prosaic surface. It seems to me at times that all this sorcery may be explained by the fact that no one on earth knows so well how to organize his successes, or rather their ‘Mise-en-scène,’ as our Franz Liszt.” Seemingly, Liszt already understood that presentation was everything.

Henryk Siemiradzki: Chopin concert

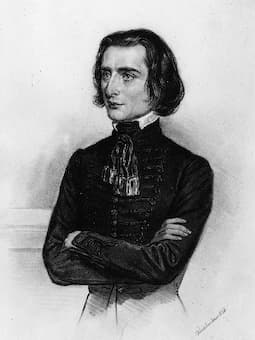

Still to this day, virtuosity is often considered negatively, “as a performance aimed at a public that outwardly demonstrates exceptional agility in terms of instrumental or vocal technique, especially as related to speed of execution. Such displays are both admired as demonstration of a divine gift and condemned as a diabolical perversion of musical practice.” In the exciting world of the piano virtuoso, Frédéric Chopin held a special position. He was described as “greater than the greatest of pianists, he is the only one.” And an admirer added “not only do we love him, we love ourselves in him.” Liszt and Chopin began their careers at roughly the same time, and whatever has been written down in the history books, they never really enjoyed a close personal friendship. Their professional and personal lives often intersected and overlapped, to be sure, as they appeared together in concerts and as part of events organized for charity, with their performances always the center of attention. Reviews referred to them as the two greatest virtuosos of the day, artists “both of whom have attained the same lofty standard and sense with equal depth to the essence of art.”

Chopin: Etude Op. 10, No. 4 “Torrent étude”

To be sure, as their relationship as friends and fellow artists developed they did hold shared admiration for each other’s talent. Liszt wrote about Chopin, “never was there a nature more imbued with whims, caprices, and abrupt eccentricities. His imagination was fiery, his emotions violent, and his physical being feeble and sickly. Who can possibly understand the suffering deriving from such a contradiction?” And tellingly he added, “Chopin’s character is composed of a thousand shades which in crossing one another become so disguised as to be indistinguishable.” Long after Chopin’s death, Liszt commented to Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, “no one compares to him; he shines lonely, peerless in the firmament of art.” Liszt never highlights the technical aspects of Chopin’s compositions, but focuses instead—as Schumann would do—on the depths of artistic expression. In a sense, virtuosity becomes a necessary evil for complex musical and personal expressions. Chopin, in turn, was critical of the purely pyrotechnical elements of many of Liszt’s compositions for the piano, but he was clearly aware of the magnetic powers of performance offered by Liszt. As he almost jealously writes to Ferdinand Hiller in 1833, “I hardly even know what my pen is scribbling, since at the moment Liszt is playing one of my etudes and distracting my attention from my respectable thoughts. I would love myself to acquire from him the manner in which he plays my etudes.”

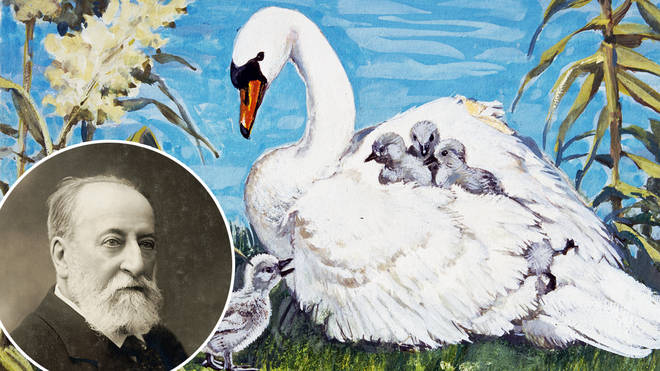

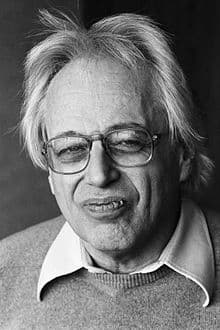

Leopold Godowsky

Heralded as the “Buddha of the Piano” among musical giants, Polish-American pianist and composer Leopold Godowsky (1870-1938) once wrote, “I love the piano and those who love the piano. The piano as a medium for expression is a whole world by itself. No other instrument can fill or replace its own say in the world of emotion, sentiment, poetry, imagery and fancy.” Musically speaking, the Chopin etudes really can’t be improved upon. However, Godowsky used them as the basis for creating over fifty monumentally difficult studies that have achieved legendary status among enthusiastic pianists. Fashioned over a number of years, these Studies reflect “Godowsky’s success as a piano pedagogue, his interest in resolving technical problems and developing pianistic vocabulary, his ambition to perfect his own mechanism, his encyclopedic knowledge of piano literature, the need to extend his own repertoire, and his unusual fascination in arranging piano works.” As a famed critic in the 1960’s wrote, “they are probably the most impossibly difficult things ever written for the piano. These are fantastic exercises that push piano technique to heights undreamed of even by Liszt.”

Chopin-Godowsky: Etude No. 25 in A-flat major

Shortly before his death in 1938, Godowsky wrote on the process of arrangement, “To justify myself in the perennial controversy which exists regarding the aesthetic and ethical rights of one composer to use another composer’s works, themes, or ideas as a foundation for paraphrases, variations, etc., I desire to say that it depends entirely upon the intention, nature and quality of the work of the so-called ‘transgressor.’ Since the Chopin Études are universally acknowledged to be the highest attainment in étude form in the realm of beautiful pianoforte music combined with mechanical and technical usefulness, I thought it wisest to build upon their solid and invulnerable foundation to further the art of pianoforte playing. Being averse to any tampering with the text of any master work when played in the original form, I would condemn any artist for taking liberties with the works of Chopin or any other great composer. The original Chopin Studies remain as intact as they were before any arrangements of them were published; in fact, numerous artists claim that after assiduously studying my versions, many hidden beauties in the original Studies will reveal themselves to the observant student.”

György Ligeti

The Hungarian composer György Ligeti composed his cycle of devilishly difficult 18 études for solo piano between 1985 and 2001. Ligeti continues in the tradition of the virtuoso piano writing seen in Chopin, Liszt and Godowsky, and his etudes are considered “the most important additions to the solo-piano repertoire in the last half-century.” Technically way beyond the abilities of mere mortals, these works are shaped from influences taken from “the polyrhythmic player-piano studies of Conlon Nancarrow to the music of sub-Saharan Africa, chaos theory to the minimalism of Steve Reich. In the Études, Ligeti effectively created a new pianistic vocabulary, while remaining exuberantly himself—the moments when the music seems to evaporate in the highest reaches of the keyboard, or flounders in its lowest depths.” The 18 études are arranged in three books of six works each.

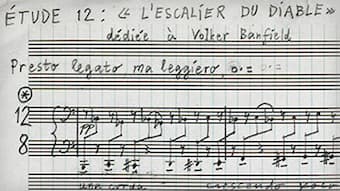

Ligeti: Etude No.13 “The Devil’s Staircase”

Originally, Ligeti had only wanted to compose twelve studies, following in the footsteps of Debussy’s Études, but he “enjoyed writing the pieces so much that he embarked on a third book.” Sadly, Book 3 is incomplete as the composed fell ill and died a couple of years later. Ligeti gave the various etudes titles containing a mixture of technical terms and poetic descriptions. In Book 1 we find “Désordre,” a study in fast polyrhythms moving up and down the keyboard, with the right hand playing only white keys while the left hand is restricted to black keys. In “Touches bloquées” two different rhythmic patterns interlock. One hand plays rapid, even melodic patterns while the other hand blocks some of the keys by silently depressing them. “Automne à Varsovie” pays homage to the annual festival of contemporary music in Warsaw Poland, and in Book II we find among others “Galamb Borong,” “Fém,” “Der Zauberlehrling,” and “L’escalier du diable” (The Devil’s Staircase). This hard-driving toccata that moves polymetrically up and down the keyboard might be the most terrifying work in the entire piano repertoire.

Charles-Valentin Alkan

In his day, Charles-Valentin Alkan (1819- 1888) was mentioned in the same breath with Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt. Not only was Alkan—he was born of Jewish parentage as Charles-Valentin Morhange—one of the most celebrated pianists of the nineteenth century, he was also a most unusual composer, “remarkable in both technique and imagination.” Alkan gave his first public concert as a violinist at age seven. By that time, he already had been a student at the Paris Conservatoire for almost 2 years, and during his piano audition the examiners reported, “This child has amazing abilities.” By age fourteen, Alkan had composed a set of piano variations on a theme by Daniel Steibelt, published as Opus 1. He soon performed in the leading salons and concert halls of Paris, and made friends with Franz Liszt, Eugène Delacroix, George Sand and Frédéric Chopin. He continued to publish piano music, including the Trois Grandes Etudes, one for the left hand, one for the right hand, and the third for both hands together. Robert Schumann commented on these pieces as follows, “One is startled by such false, such unnatural art…the last piece titled ‘Morte’ is a crabbed waste, overgrown with brush and weeds…nothing is to be found but black on black.” By the age of 25, Alkan had reached the peak of his career, with Franz Liszt providing glowing reviews of his performances and even recommending him for the post of Professor at the Geneva Conservatoire. And his “Train Journey” must be one of the most demanding etudes in the piano repertoire.

Jean-Amédée Lefroid de Méreaux

We could seemingly go on forever and find fiendishly difficult and often musically satisfying etudes by Alexander Scriabin, Anton Rubinstein or Moritz Moszkowski, to name only a selected few. But I wanted to conclude this blog with an etude by the relatively little-known Jean-Amédée Lefroid de Méreaux (1802-1874). A French composer, pianist, piano teacher, musicologist and music critic, he was initially groomed to enter the legal profession, but he also received first prize in a piano competition at the Lycée Charlemagne. Desperate to pursue a career in music, he was allowed to take harmony lessons from Anton Reicha at the Conservatoire de Paris, and he published his first works at the age of 14. Today, he is probably best known for his 60 Grandes Études, Op. 63, compositions of immense technical difficulty. Marc-André Hamelin considered them more difficult than those of Charles-Valentin Alkan. However, he also calls them unmusical. This simple statement underscores the idea that rapid velocity, large intervals within very short periods of time, escalations of ornamentation and variations, notes doubled an octave apart are “processes of pointless acrobatics and soulless agility.” We all know that virtuosity can be seen as an elaborate magic trick, but does this make it any less exciting? Even the digital midi version of the “Scherzo alla Neapolitana” offers plenty of excitement, don’t you think?