by Georg Predota

Niccolò Jommelli

The above quote originates in a letter from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to his father Leopold. Mozart was in Naples in 1770 and had just seen a performance of Armida abbandonata, judging it beautiful but rather old fashioned. Mozart’s opinion notwithstanding, Jommelli was considered one of the leading operatic composers in Europe in his day.

Born in Naples, Niccolò Jommelli (1714-1774) composed roughly 80 operas and a substantial corpus of church music. He worked in Rome, Bologna, and Venice, and visited Vienna to strike up a friendship with the librettist Metastasio. Appointed Kapellmeister to the Duke of Württemberg, he spent over 15 years in Stuttgart before returning to Naples.

Legacy and Beginnings

An important transitional figure, Jommelli was anticipating the mid-18th-century operatic reforms, gradually abandoning da capo arias and introducing dramatic recitative. According to scholars, his greatest achievements represent “a combination of German complexity, French decorative elements and Italian brio, welded together by an extraordinary gift for dramatic effectiveness.”

Jommelli came from a wealthy merchant family, and having shown early talent for music, began his training under Canon Muzzillo, director of music at the local cathedral. After further studies at the Naples Conservatory, Jommelli began his public career with two comic operas for Naples in 1737 and 1738. A contemporary composer exclaimed, “this young man will claim the astonishment and admiration of all Europe.”

Early Successes

Teatro italiano. Metatasio . Didone abbandonata, drammi di P.

The resounding success of his first serious opera Il Ricimero, staged in Rome in 1740, brought him to the attention of the seriously wealthy and influential patron, Cardinal Henry Benedict, Duke of York. An early enthusiast wrote, “This young man promises to go far and to equal before long all that was ever done by the great masters. He has strength as well as taste and delicacy; he possesses a basic understanding of harmony, which he displays with astonishing richness.”

But, what really impressed audiences was Jommelli’s handling of the obbligato recitative. At the Conservatory, Jommelli had been a student of Johann Hasse, a composer who experimented with motivic orchestral writing to create an intensified emotional effect at theatrical movement. Jommelli took that idea on board and “the force of the declamation, the variety of the harmony and the sublimity of the accompaniment created a sense of drama greater than the best French recitative and the most beautiful of Italian melody.”

Bologna and Venice

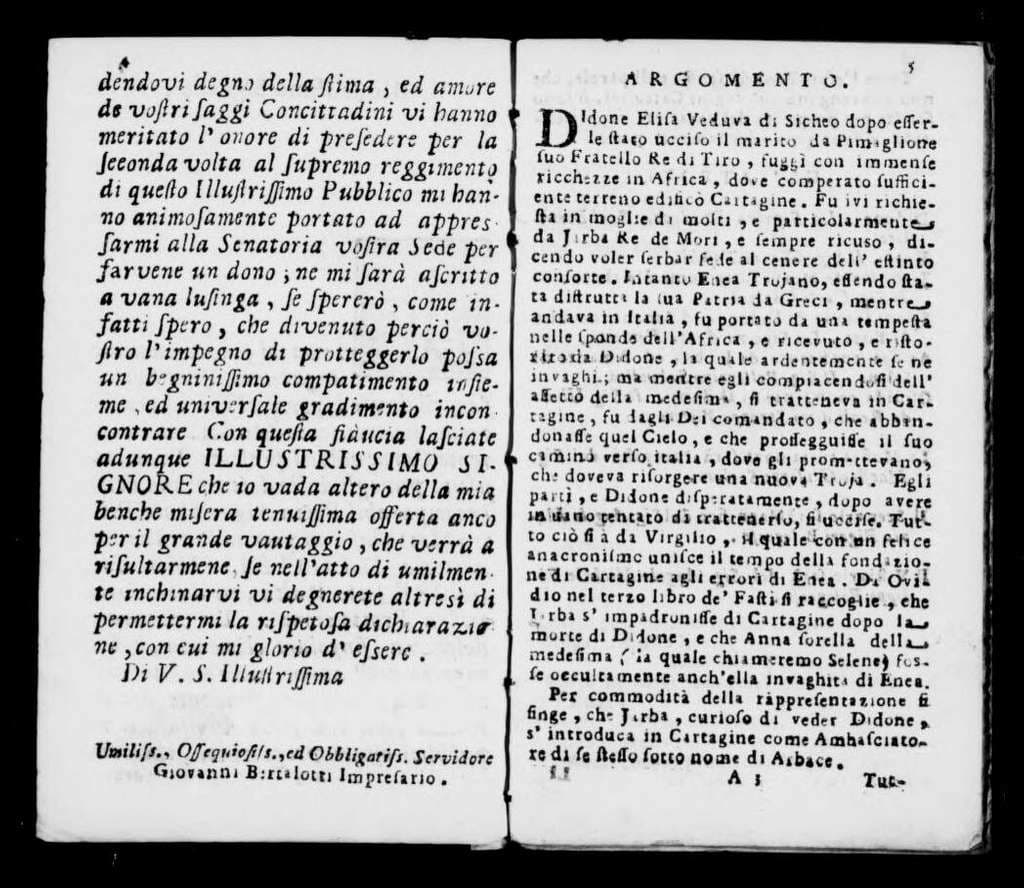

Didone abbandonata’s libretto

After the success of his first opera for Rome, Jommelli moved to Bologna to work with famed librettist Pietro Metastasio on a production of Ezio, and took lessons with “Padre” Martini. For roughly two years, Jommelli wrote operas for a variety of northern Italian cities, including Vencie, Turin, Ferrara, and Padua. He also wrote two widely performed oratorios, Isacco figura del Redentore and La Betulia liberata.

Around 1743, Jommelli received, on Hasse’s recommendation, his first permanent position in Venice. He was appointed musical director of the Ospedale degli Incurabile, one of the city’s conservatories for girls. He composed music for church services and sacred works for women’s voices in a great variety of movement types, keys, choruses, arias and ensembles.

Rome

In addition, he continued to compose for the theatre, with the characteristics of his mature style emerging. According to scholars, elements of that style include “the incursion of declamatory elements in the aria, audacious harmonic effects, abundant modulations, chromaticism, and the exploration of orchestral resources such as the use of the second violin as an independent textural element, the occasional independent viola parts, the abundant dynamic indications and the development of the crescendo effect.”

Jommelli departed for Rome around 1747 and was soon employed at the Papal Chapel. In this position, he composed a prodigious amount of liturgical music, including sacred works for soloists and chorus in the concertato style. He also received commissions to write a number of cantatas and theatrical pieces for special occasions, and he took advantage of several opportunities to write comic opera.

Vienna

In Rome, Jommelli met Cardinal Albani, which secured him a commission in Vienna. He probably stayed for a year and a half, and his operas were considered “unrivalled in their ability to seize the heart of the listener with delicate and sensitive melodies.” In fact, the early Viennese symphonists, among them Dittersdorf and Wagenseil, later acknowledged Jommelli’s influence on the formation of their symphonic style.

Jommelli returned to Rome and had a demanding schedule of opera composition. Over the next four years, he secured commissions from Rome, Spoleto, Milan, Piacenza and Turin. His “concern for the musical realisation of textual imagery found expression not only in a subtly responsive vocal line but also in orchestral word-painting, in sensitive textural variation suited to the changing moods of the poetry, and in programmatic effects.”

Stuttgart

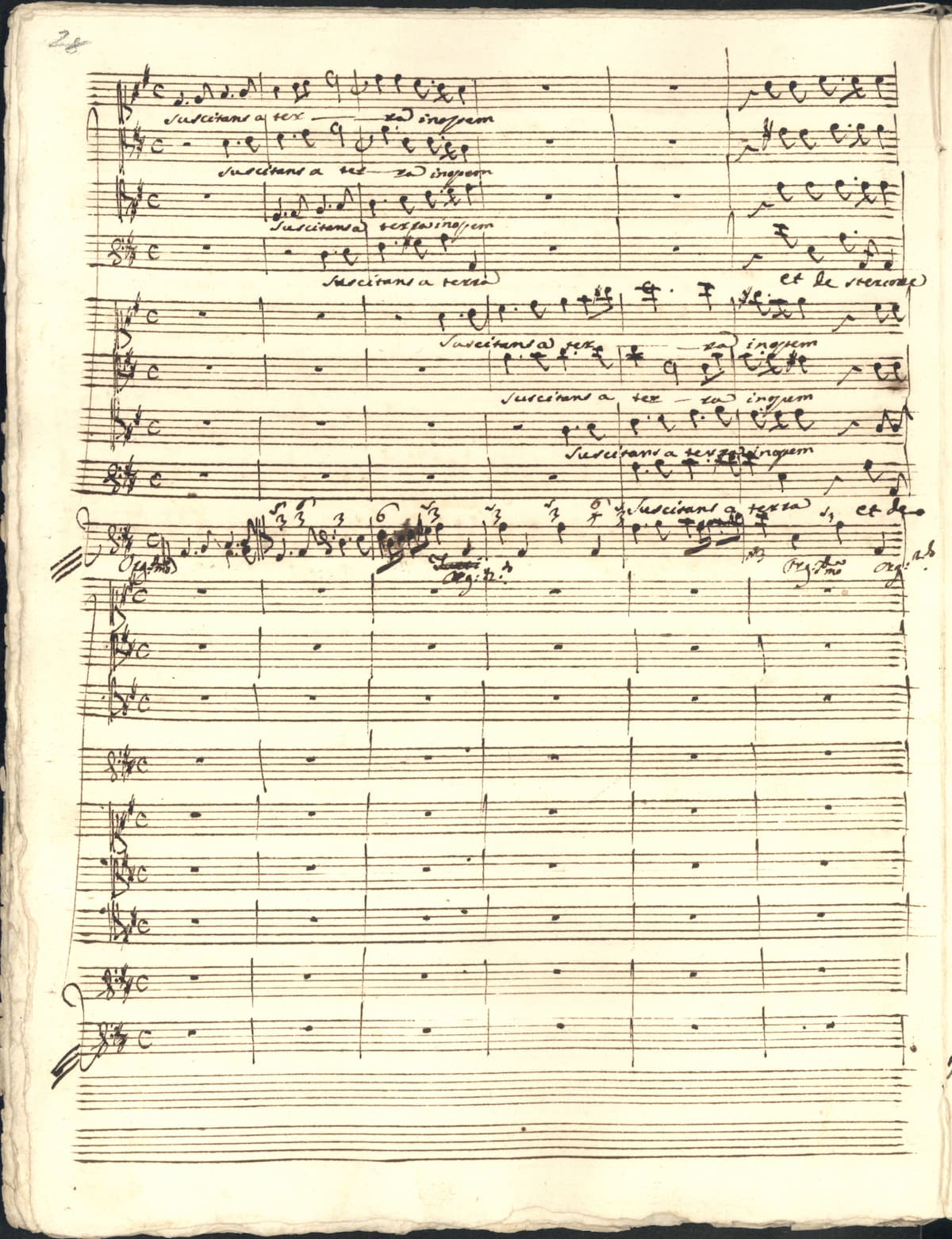

Niccolò Jommelli’s autograph

By 1753, Jommelli was at the height of his fame. He had already received offers for positions in Mannheim and Lisbon, but he was hired by the Duke of Württemberg to join the court in Stuttgart. Italian opera was well established, and by 1754, he assumed the duties of Kapellmeister at the Stuttgart court. Stuttgart had spared no expense to attract the best instrumentalists, singers, dancers, and designers.

Jommelli quickly understood the dramatic possibilities of the orchestra, and he built one of the finest ensembles in Europe. In his operas, he radically departed from the traditional succession of recitatives and exit arias. Librettos were based on mythology rather than historical subjects, and the librettos freely “combined obbligato recitative, aria, ensemble, chorus and programmatic orchestral music in dramatic scene complexes and spectacular, French-inspired finales.”

Historical Position

The Stuttgart operas of Jommelli secured his position as one of the reformers of 18th-century opera. He used music to express the poetry, moving away from the da capo aria as a vehicle of vocal virtuosity. Instruments are used in recitative to interpret the words, and the lines between recitative and aria continue to blur. Equally important, the orchestra is used to advance the dramatic argument.

Jommelli was greatly appreciated by German critics, but Italian voices were less enthusiastic. Once Jommelli returned to Naples in 1768, opera buffa had become extremely popular and Jommelli’s opera seria were not well received. Jommelli suffered a stroke in 1771 and was partially paralysed. He continued to work until his death on 25 August 1774.

Recognition

Immediately after his death, Jommelli was regarded as one of the greatest composers of his time. As the music journalist and philosopher Schubert wrote, “If richness of thought, glittering fantasy, inexhaustible melody, heavenly harmony, deep understanding of all instruments, and particularly the full magical strength of the human voice—if great art affects entirely each chord of the human heart, if all these—yet combined with the sharpest understanding of musical poetry—constitute a musical genius, then in Jommelli Europe has lost its greatest composer.”