by Emily E. Hogstadt, Interlude

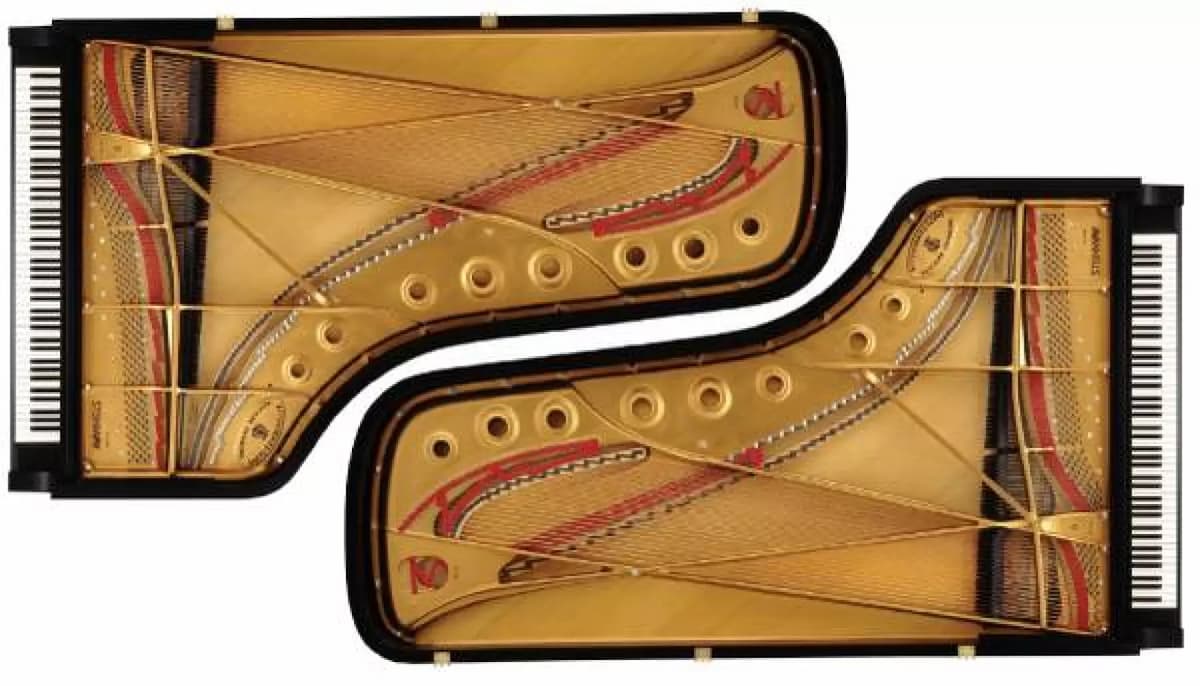

© wshu.org

Today we’re looking at six of the most famous piano duels in the history of classical music, from the time Mozart was pitted against a rival on Christmas Eve in a Viennese palace to the time Liszt and his greatest rival trying to settle the question of who was best in a sparkling Romantic Era Paris salon.

Let’s get started!

Bach vs. Marchand (1717)

In 1717, when Bach’s work travels took him through Dresden, he unknowingly walked into a veritable snake’s pit of musical intrigue.

An irascible musician named Louis Marchand, who had left (or possibly been fired) the French royal court, was visiting Dresden at the same time that Bach was.

J.S. Bach © ClassicFM

Dresden-based musician J.B. Volumier feared that Marchand would be hired in Dresden and become a rival. So he began scheming to get Marchand out of the way.

He started by offering Bach an opportunity to hear Marchand practice. Volumier kept Bach “concealed” so that Marchand wouldn’t know anyone was listening.

Bach was then encouraged by courtiers to challenge Marchand to a duel. Since he’d just heard Marchand play and felt confident that he’d win in a head-to-head battle, he agreed.

The scheduled time for the face-off arrived, with a variety of wealthy and powerful people assembling to watch the musical carnage. Then came a shocking twist: Marchand had taken an early morning carriage and vanished from the city altogether.

It is theorized that Volumier may have sneaked Marchand into one of Bach’s practice sessions and that Volumier was so intimidated by what he heard there that he left town rather than embarrass himself onstage.

Louis Marchand

One caveat: eliable biographical details about Bach’s life are scarce, and it’s unclear exactly how much of this story is true. It has likely been embellished over the generations. But it remains one of the most famous keyboard duels of all time, whether it actually happened or not.

Handel vs. Scarlatti (1709)

George Frederick Handel and Domenico Scarlatti were born in 1685. By their mid-twenties, they both had earned major reputations as organ and harpsichord players.

In 1709, a cardinal and patron of the arts named Pietro Ottoboni was keeping court at the Palazzo della Cancelleria. Both Handel and Scarlatti were present, and they challenged each other to a friendly duel.

The night of the duel arrived. There would be two rounds to the competition. One would compare the musicians’ abilities on harpsichord, the other on organ.

Scarlatti won the harpsichord round; Handel won the organ round. In the end, the competition was labeled a draw.

Mozart vs. Clementi (1781)

Mozart vs Clementi

In 1781, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart moved to Vienna to pursue a career as a freelance musician.

His reputation had spread far and wide, and on Christmas Eve, he was summoned by the Emperor. He wanted Mozart to have a musical duel with an Italian pianist currently making a splash in Vienna, a man named Muzio Clementi.

Clementi later remembered, “On entering the Emperor’s music room, I found there someone whom, because of his elegant appearance, I took for one of the Emperor’s chamberlains; but scarcely had we begun a conversation when we soon recognized each other as Mozart and Clementi.”

The two got down to business. Clementi began by playing one of his own sonatas; Mozart replied by playing an improvisation. Next came a sight-reading competition.

In the end, the assembled aristocrats declared the evening a draw, and prize money was split between the two men.

But the Emperor had a private side-bet going. He had bet on Mozart winning, while his Italy-loving sister-in-law bet on Clementi. Later, the Emperor, privately believing that Mozart had performed the best, collected his money from her.

Beethoven vs. Woelfl (1798)

Joseph Woelfl was born in 1773 in Salzburg and studied music under Mozart’s father. In 1790, he moved to Vienna to find work as a musician.

Beethoven also moved to Vienna in 1792. Cliques of fans soon arose. Some preferred the genial, gentler style of Woelfl, while others gravitated toward the stormy virtuosity of Beethoven.

Joseph Woelfl © Wikipedia

Woelfl also had a striking biological advantage: his fingers were freakishly long, allowing him to reach the interval of a tenth on the keyboard.

In 1798, the two men agreed to a piano duel and carried it out. In the end, Beethoven was declared to be the winner.

Woelfl was unbothered. In fact, he underlined his admiration for Beethoven by publicly dedicating a 1799 piano sonata to him.

Beethoven vs. Steibelt (1800)

Daniel Steibelt was born in 1765 in Berlin. His father forced him to join the military, but he deserted and began a career as a piano virtuoso and composer instead.

In March 1800 he arrived in Vienna. Beethoven was not thrilled about this newcomer trying to usurp his place. They ended up meeting at the home of nobleman and banker Count Moritz von Fries to settle their differences with a good old-fashioned piano duel.

Daniel Steibelt

The duel featured three rounds. The first consisted of playing another composer’s work. Beethoven played a Mozart work; Steibelt played a Haydn work. Beethoven won.

The second round required the participants to improvise on a theme supplied by the other man. Beethoven won this round, too. By this time, Steibelt was surely sweating.

The third round would be the most challenging of all: sight-reading a work composed by the other man. Beethoven chose to pass along his eleventh piano sonata, which Steibelt interpreted very ably.

Steibelt then made a daring move: he handed Beethoven not a sonata for piano, but a sonata for piano and cello. Beethoven took the sheet music, turned it upside down, read it, and began improvising on themes from it.

According to legend, Steibelt left the room in a huff.

We don’t know exactly how much of this story is true. The most extensive record of it comes from a man named Ferdinand Ries, who wrote the account decades later, and who was also a friend and ally of Beethoven, with every incentive to make him look good. But regardless of if the details are accurate, it’s a great story.

Liszt vs. Thalberg (1837)

The duel between Franz Liszt and Sigismund Thalberg is probably the most famous piano duel in the history of classical music.

In 1837, these two young virtuoso pianists were taking Paris by storm. That March, writer and journalist Countess Cristina Belgiojoso – once the wealthiest heiress in Italy, and a supporter of Italian revolutionaries – invited Liszt and Thalberg to participate in a duel. Proceeds from the event would go to Italian refugees.

Each man played a series of their own works, including wildly flashy and virtuosic variations on operatic themes, which were extremely popular at the time.

Franz Liszt vs Sigismond Thalberg

The savvy countess, not wanting to alienate either giant, famously proclaimed, “Thalberg is the greatest pianist, but there is only one Liszt.”

Critic Jules Janon was more descriptive when he wrote about the event the following day:

Never was Liszt more controlled, more thoughtful, more energetic, more passionate; never has Thalberg played with greater verve and tenderness. Each of them prudently stayed within his harmonic domain, but each used every one of his resources. It was an admirable joust. The most profound silence fell over that noble arena. And finally Liszt and Thalberg were both proclaimed victors by this glittering and intelligent assembly. Thus two victors and no vanquished.