By Emily E.Hogstad, Interlude

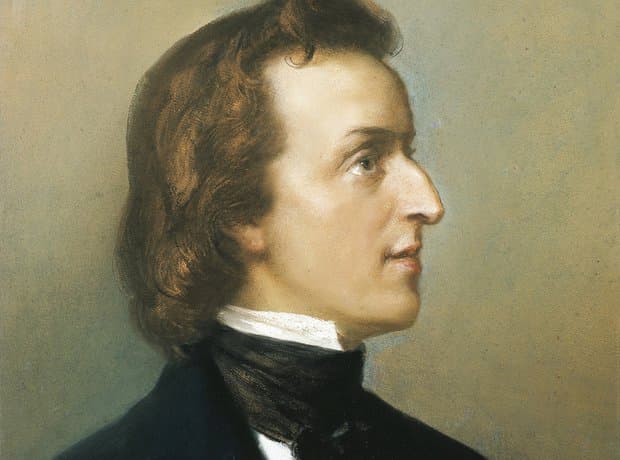

Frédéric Chopin © ClassicFM

That said, Chopin’s music doesn’t have a monopoly on those adjectives.

Today, we’re looking at ten works by ten composers who, just like Chopin, understood the piano’s expressive power…while forging their own creative identities, too.

If you’re looking for music like Chopin’s, here are ten suggestions for your playlist:

John Field (1782-1837)

Pianist and composer John Field was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1782.

He studied with Muzio Clementi in London and toured Europe with him, finally settling in St. Petersburg in 1802.

John Field, 1820

In his late twenties, he began experimenting musically. He started writing short pieces for solo piano featuring an arpeggiated accompaniment in the left hand and a highly chromatic melody in the right hand. These pieces would usually be poetic and melancholy in nature. He called them “Nocturnes.” And so a new genre of piano music was born, that Chopin would later perfect.

You can hear Field’s influence in Chopin’s nocturnes.

Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831)

Maria Szymanowska was born Marianna Agata Wołowska in Warsaw in 1789.

Maria Szymanowska

In 1810, she married a man named Józef Szymanowski, a wealthy landowner, and she also made her public debut as a pianist.

Many women musicians of this era gave up their careers once they got married, but not Szymanowska. Ultimately, she split from her husband and began touring Europe, spending a great deal of time in St. Petersburg. (And in case you’re wondering, yes, she did cross paths with Field!) She died there in 1831 during a cholera epidemic.

Musicologist Sławomir Dobrzański writes, “Szymanowska’s musical style is parallel to the compositional starting point of Frédéric Chopin; many of her compositions had an obvious impact on Chopin’s mature musical language.”

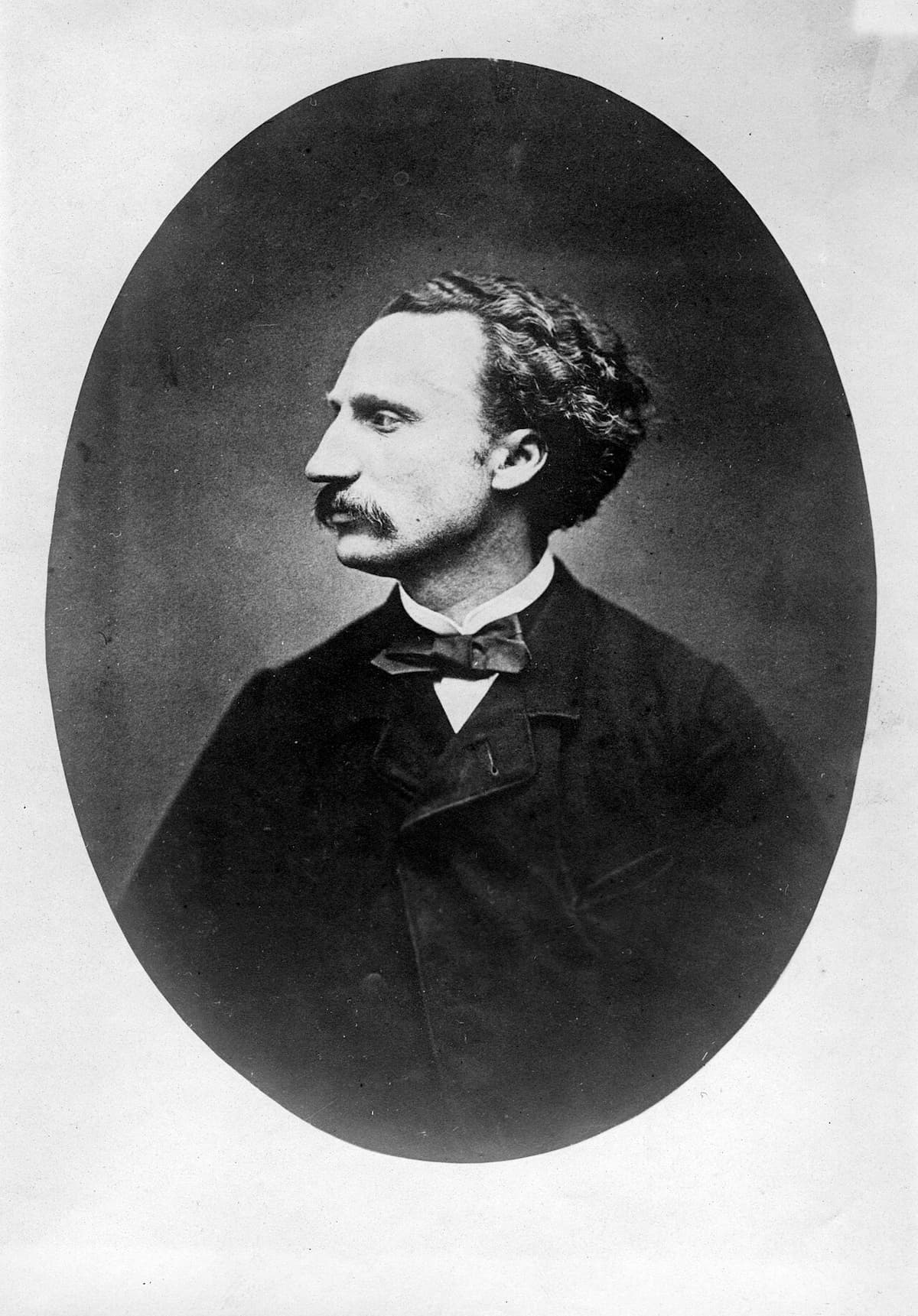

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857)

Glinka was born in Russia in 1804. He attended a school in St. Petersburg for children of the nobility and took three lessons from John Field while there.

Portrait of Mikhail Glinka, 1840

When he became an adult, he joined the Foreign Office, but by night, he kept pursuing music. He ultimately developed a great passion for expressing Russian nationalism in music, and encouraging a specifically Russian school of music.

Most of his best-known music dates from after that revelation. However, the music from his young dilettante days – like this Nocturne from 1828 – feels similar in some ways to Chopin’s and certainly reveals Field’s influence.

Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Liszt and Chopin met at the latter’s first Parisian concert in 1832. They moved in the same aristocratic Parisian circles and their lives shared important themes, chief among them their devotion to their respective homelands (Hungary and Poland).

Franz Liszt, 1847

They respected each other a great deal, and Liszt was deeply saddened by Chopin’s early death in 1849. Liszt went so far as to write a biography in memory of his friend.

It is believed that Liszt’s third Consolation in D-flat major is modeled after Chopin’s Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2. This piece by Liszt was published in 1850, the year after Chopin’s death.

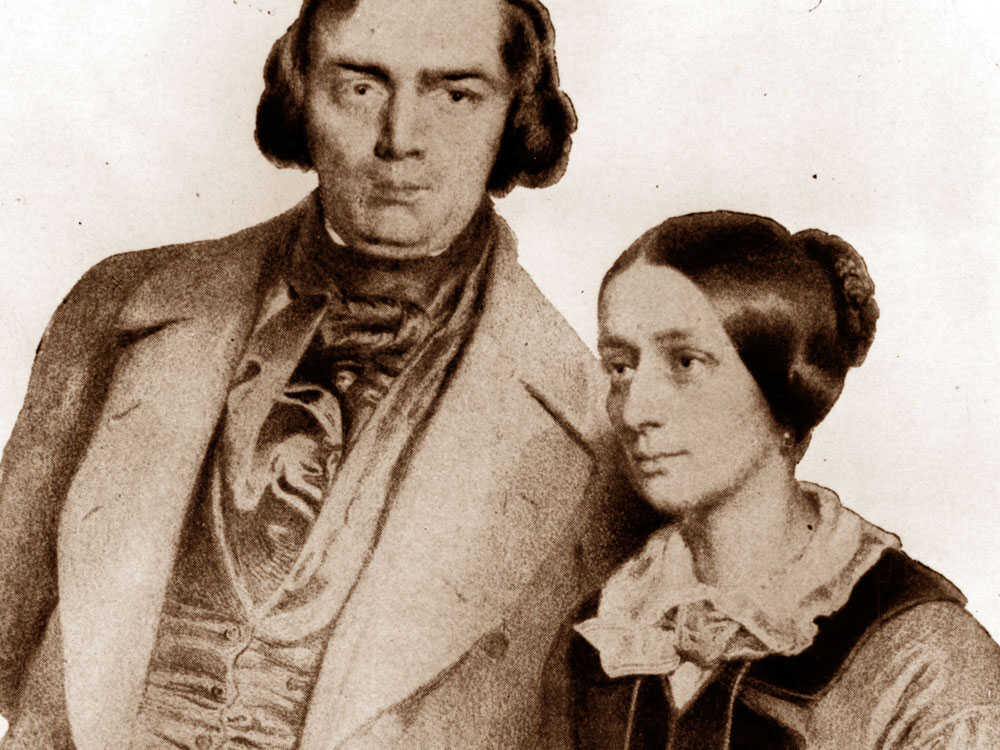

Clara Schumann (1819-1896)

Clara Wieck, who became known as Clara Schumann after her marriage to composer Robert Schumann, began championing the works of Chopin when she was a child prodigy touring across Europe.

Robert and Clara Schumann

In 1832, the same year that Liszt and Chopin met, a young Clara Wieck heard Chopin in concert. She never forgot the experience.

Clara Wieck Schumann was always excited to play any new music that Chopin would write. She continued playing Chopin for decades after his death at important and prestigious venues, helping to ensure that he would stay in the repertoire. She ultimately emerged as one of the greatest pianists of her generation, and she brought Chopin’s music with her on that journey.

When Chopin came to visit her in 1836, she played this Chopinesque nocturne for him, as well as a variety of other pieces. He was delighted.

Thomas Tellefsen (1823-1874)

Pianist and composer Thomas Tellefsen was born in Trondheim, Norway, in 1823.

As a young man, it became his dream to study with Chopin, and so he left his native Norway for Paris.

Thomas Tellefsen

Unfortunately for Tellefsen, however, not just anyone could study with Chopin; he was in high demand as a teacher.

Luckily, in 1844, Chopin’s partner, authoress George Sand, put in a good word for Tellefsen, and Chopin accepted him as a student. Chopin was impressed by his talent, and eventually, the two men became friends and traveling companions.

Chopin viewed Tellefsen as a major pedagogical heir, tasking him with writing a pianoforte method based on what he’d learned. However, if Tellefsen did complete it, no record of it exists.

What does exist are his compositions in a style a la Chopin.

Carl Filtsch (1830-1845)

Carl Filtsch was born in present-day Romania in 1830. He was a child prodigy, and his family relocated to Paris when he was eleven so he could take lessons from Chopin.

Chopin didn’t teach children, but he made an exception for Filtsch. Indeed, he started teaching him three lessons a week.

Carl Filtsch

Filtsch eventually began touring Europe to acclaim, but he died of tuberculosis in Venice when he was only fifteen years old.

One of Chopin’s friends wrote in 1843 that, “My God! What a child! Nobody has ever understood me as this child has…It is not imitation, it is the same sentiment, an instinct that makes him play without thinking as if it could not have been any other way.”

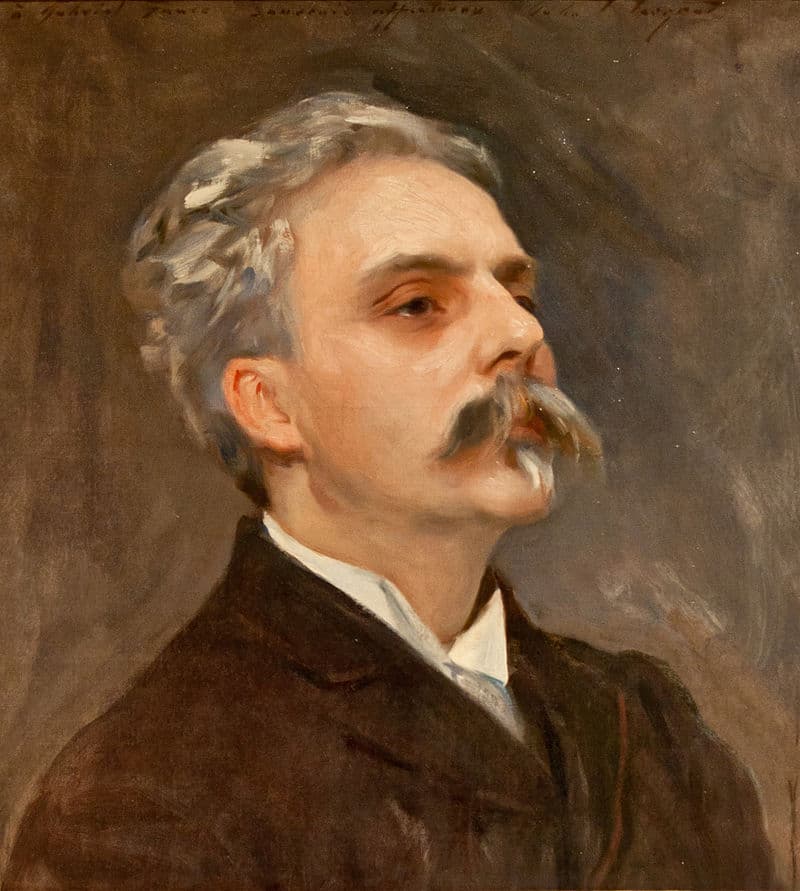

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Play

Chopin died when Fauré was only a few years old, but something about Chopin’s brand of poignancy and elegance spoke to the Frenchman. When Fauré began writing his own nocturnes in the mid-1870s, he reached back to an earlier generation for inspiration.

John Singer Sargent: Gabriel Fauré, 1896

Fauré, like Chopin, was obsessed with writing for piano. “In piano music, there’s no room for padding – one has to pay cash and make it consistently interesting. It’s perhaps the most difficult genre of all,” he wrote.

His first nocturne, dating from ca. 1875, features an opening theme that immediately recalls to mind Chopin’s Prelude in E-minor.

Even when the nocturne wanders into more experimental harmonies or rhythms, a Chopinesque character still remains.

Juliusz Zarębski (1854-1885)

Juliusz Zarębski was born in 1854 in present-day Ukraine, a country that in the past had been under Polish rule. His hometown Zhytomyr is between Kyiv (two hours away by car) and Warsaw (nine hours).

Juliusz Zarębski

Zarębski studied in Rome and St. Petersburg as a young man, taking lessons from Liszt and setting to music work by poet Adam Mickiewicz (who, interestingly, was Maria Szymanowska’s son-in-law). He spent formative time in places that were deeply influenced by Chopin’s own influences, and it shows.

Tragically, his life path followed Chopin’s in a grim way: he became ill with tuberculosis and died at the age of 31. He left behind a catalog of lovely music, perfect for a Chopin listener looking for something fresh.

Rosemary Brown (1916-2001)

Rosemary Brown was a psychic medium from twentieth century Britain who claimed to channel the works of the great composers.

Rosemary Brown

The story of Rosemary Brown’s musical career is odd and fascinating. To make a long story short, Brown said that she could communicate with dead composers. (For what it’s worth, she claimed that Chopin was horrified by television.)

During their interactions, the composers dictated pieces to her in a variety of ways. She said that Chopin wrote this one.

Is this piece really Chopin composing from the afterlife? Well, frankly, deciding that is a bit beyond our pay grade, but you’re free to believe whatever you want! If nothing else, it’s a great story.

Conclusion

Regardless of what you think about the work of Rosemary Brown, here’s the truth: Chopin didn’t need a psychic medium to speak through the music of those who came after him.

Many composers shared his artistic priorities and delicate touch and wrote incredibly poignant, romantic pieces of Chopinesque music that we can still enjoy today. We hope you enjoy our picks!