by Georg Predota, Interlude

Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125

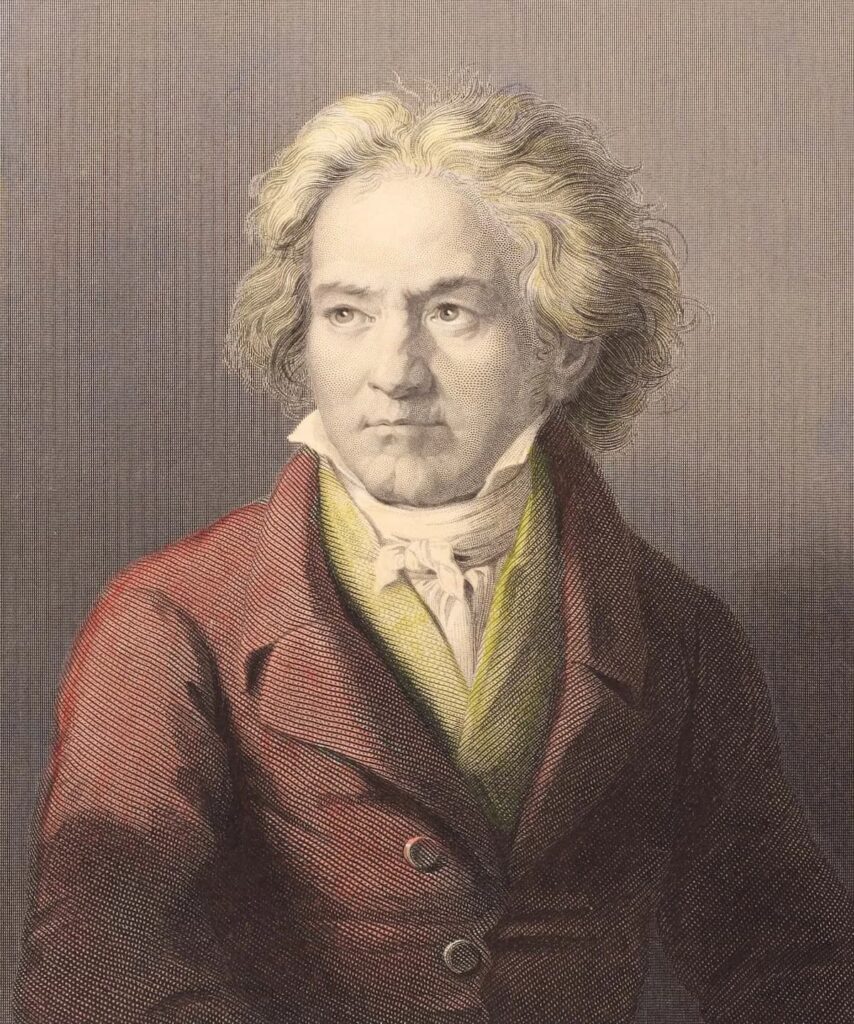

Ludwig van Beethoven was a revolutionary man who lived and worked in tumultuous times as the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars greatly destabilised the European continent. For over two decades of Beethoven’s life, Napoleon was the most powerful man in Europe, an authoritarian who almost succeeded in unifying the continent under French hegemony.

In some works, as Jürgen Thym explains, “Beethoven gave voice to events that were occurring on the political and military level.” The “Bonaparte Symphony,” eventually subtitled “Eroica,” became a celebration of a hero and the musical representation of the ideal of heroic greatness. However, when Beethoven learned that Napoleon had crowned himself Emperor in 1804, he angrily tore up the title page containing the original dedication. And let’s not forget that he gave voice to the demise of the dictator in his highly popular “Wellington’s Victory.”

Ludwig van Beeethoven

The Human Perspective

Beyond the complex and seemingly incomprehensive enormity of Beethoven’s music, we find a man who was thoroughly human. Much has been written and made about his deafness and its impact on the creative process. It predictably affected his mental health by creating a sense of deep isolation and frustration that informed his interaction with society at large.

Beethoven had a small number of close male friends, and most of the women he admired were happily married, committed to somebody else and usually of higher social standing.

Eternally, in search of “tranquillity and freedom,” he showed utter disdain for discipline and authority and, unable to adopt a submissive attitude, brusquely dismissed the conventions of aristocratic society.

In Beethoven, we discover a fragmented individual who is full of contradictions. He struggled with a severe disability, a failing body, mental instability and an alcohol addiction. Once we add his volatile temperament, unrequited love and dreadful communication and social skills to the thorny mix, it becomes clear that composing and the discipline associated with his art was the personal therapy that confidently anchored the sinking ship.

Defiance

Beethoven’s ear trumpets

By 1814, Beethoven had become profoundly deaf, unable to perform in public, unable to hear music, and unable to talk with friends. This silence, which had slowly enveloped the composer beginning in the late 1790s, halted the enormous productivity of his heroic period and led to four years of almost complete inactivity.

The monumental pieces of his “late period” started to take shape in 1819, and the Ninth Symphony emerged as the result of a commission from the London Philharmonic Society in 1821. Completion of the work was delayed until 1824, and Beethoven actually pondered the possibility of concluding his symphony with an instrumental finale. As William Kindermann explained, “a passionate melody in D minor was eventually used in the A-minor String Quartet Op. 132, as Beethoven opted for an affirmative ending.”

Ode to Joy

By appealing to the spirit of Romanticism and the shared ideals of humanity as expressed in Schiller’s “Ode to Joy,” the composer appeared to have made not only a musical point but also issued a decisive cultural statement. As a cultural artefact, Beethoven’s celebration of universal brotherhood has been questioned. However, the utopian ideals expressed are once again highly relevant.

Today, the “Ode to Joy” is the anthem of both the European Union and the Council of Europe. Its described purpose is to “honour shared European values, expressing the ideals of freedom, peace, and unity.” In fact, it has become a trans- and international anthem, “a beacon of hope and community.”

ARTE CONCERT

Beethoven’s “Choral Symphony” first sounded at the Theater am Kärntnertor in Vienna on 7 May 1824. To commemorate the 200th anniversary of this memorable event, ARTE is celebrating Beethoven the European by presenting a special celebration of this work; individual movements are performed in four of the most important concert venues across Europe.

Conductor Andris Nelsons opens the festivities at the Gewandhaus in Leipzig, the location of the premiere of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5, also known as the “Emperor Concerto.” The European journey continued in Paris, as the Orchestre de Paris was the first French orchestra to play Beethoven’s symphonies shortly after the composer’s death. For the “Scherzo” movement, the Philharmonie de Paris is in the capable hands of Klaus Mäkelä.

Next, Riccardo Chailly takes us to Milan. He conducts the Orchestra del Teatro alla Scala in a performance of the “Adagio e molto cantabile,” a melancholy and pensive, some would say, brooding movement. The crowing conclusion takes place at the Konzerthaus in Vienna, with Petr Popelka conducting the Vienna Symphony with soloists Rachel Willis-Sørensen, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, Andreas Schager, and Christof Fischesser.

Andris Nelsons © Marco Borggreve

Klaus Makela © Marco Borggreve

Riccardo Chailly © riccardochailly.com

Petr Popelka © Susanne Hassler-Smith

Assessment

By artistically realising the potential for freedom and optimism within all of us, Beethoven’s music has not only transcended the mundane and the narcissistic, but it is still capable, as it has done in the past, of successfully challenging regressive political ideology. As the world is becoming increasingly fractured and polarised on countless issues, humanity needs Beethoven’s optimism even more urgently today than it did 200 years ago.